Thomas Krebs

Operetta Research Center

8 January, 2020

How many female operetta composers can you name? Here is one who was also a baroness, no less. Her operetta Kavalier Jack was performed at least a hundred times in Berlin at the height of the Roaring Twenties.

Carita von Horst, née Partello, sitting at the piano. (Photo: Archive von Horst family)

Carita von Horst, née Partello (1864-1935) was an American who lived most of her life in Germany. She studied music, piano and composition in Stuttgart where she became friends with the four daughters of the Grand Duchess Marie of Russia. Her father, Dwight J. Partello, was US consul in Düsseldorf and the owner of one of the largest collections of rare and valuable violins, among them a Stradivari that had belonged to the Tzars of Russia.

The Partello family claimed lineage going back to William I the Lion, King of Scotland. Carita’s husband, Louis von Horst, was a German-born American businessman, the largest hops dealer in the US. In 1892 he married Carita and they moved to Germany, living in Coburg. In 1899 Louis von Horst was made a baron by the Duke of Coburg-Saxe-Gotha, and Carita became a baroness. In 1909 the von Horsts founded an opera school for American students in Coburg.

The Oakland Tribune reported on this in August 1912:

“A revolution in the education of American music students in Germany has been started by the handsome Baroness Carita von Horst, herself an American. Married to Baron Louis von Horst and possessed of great wealth, this American woman has undertaken to divert the music students of the United States from Berlin to Coburg, where she has opened a large conservatory, with the approval of the Grand Duchess Marie of Russia.

Berlin dispatches announce that the Grand Duke Cyril has accepted the honorary presidency of the Coburg conservatory, and that among the vice-presidents are Crown Princess Marie of Romania, Princess Beatrice and Princess Alfons of Orleans-Bourbon and the Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia.

Being wealthy and having no need of making the Coburg conservatory profit-paying, all surplus earnings from the institution are to be used by the baroness for free scholarship for talented Americans.

Piano and voice culture lessons in Berlin under the best instructors cost from USD 5,- to 20,- a half hour. The baroness proposes to make the fees to Americans at Coburg so low that the tuition for a month will be less than a single lesson in Berlin.

Duke Carl of Coburg has expressed a keen interest in the project of the baroness and has promised to provide a chance in the Royal Opera House to any student showing talent. Coburg is a wonderfully quaint city 800 years old. It is within a short distance of Bayreuth and a number of other opera centers.”

The opera school was run successfully for a few years, but in 1914 Baron von Horst was arrested as a German spy by the British and interned for the duration of the war. He was to go on trial, but this never materialized due to lack of evidence. Nevertheless, in 1919 the British expelled him to his alleged home country, Germany as an undesirable alien, although he was in fact innocent of the charge of being an agent provocateur.

He and his wife lost their entire fortune during the war, but they still had their mansion in Coburg and their works of art.

Carita von Horst had written about 50 songs and some pieces for cello and piano when it was announced in 1921 that the Theater in Coburg was going to produce her opera Die beiden Narren (The Two Fools). No reviews of this have come to light so far, so it is not known how successful the opera was. It was apparently not her first work for the stage: According to reports in both Musical America and the Brandon Weekly Sun in 1912 Horst had completed the score of an operetta The Gypsy Girl, “on which she has been working for a long time. The critics say the music is the sweetest and dreamiest they have ever heard.” Since it has not been possible to find any trace of this operetta one wonders who those critics were.

In a 1924 letter to the Prince of Fürstenberg, the founder of the Donaueschingen music festival, she wrote that six songs (of about 50 she had composed) had been published by Bote & Bock and three cello pieces by Schlesinger. No orchestral, piano or other chamber music composed by her is known.

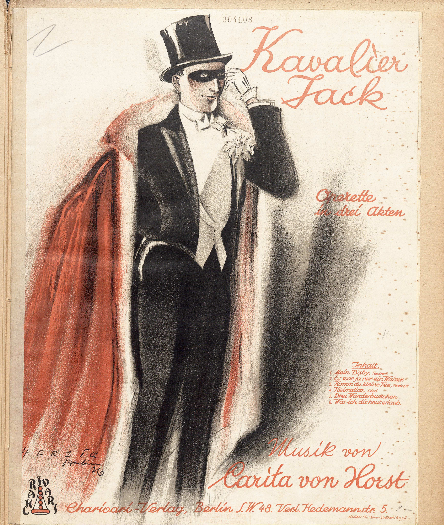

The sheet music cover of “Kavalier Jack.” (From the music collection of Staatsbibliothek Berlin)

The operetta production team for Kavalier Jack represented three generations – the composer in her early sixties, the librettist Theo Halton, aged 50, and the song lyricist Ernst Neubach, 25 years old.

Halton (1875-1940), whose real name was Heß, started out as an engineer before he became an author of over 70 works for the stage, among them the operetta Mädels von Davos by Martin Knopf. The journal Der Humorist referred to him as Viktor Hollaender’s “house poet” in a 1916 article.

Composer Victor Hollaender.

Ernst Neubach (1900-1968) was one the most prolific lyricists and librettists of the 1920s and early 30s, the self-declared author of 2.000 bad songs, among which are such perennials as “Ich hab’ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren” (I lost My Heart in Heidelberg) or “In einer kleinen Konditorei” as well as the Hans May songs made famous by Joseph Schmidt: “Ein Lied geht um die Welt” (My Song Goes Round the World) and “Heut ist der schönste Tag in meinem Leben.”

Neubach was also a film director and producer. Being Jewish, he had to escape from Vienna in 1938 and emigrated to France. More on his life and career can be found here (in German):

The first performance of “Gentleman Jack”, as the operetta was then called, took place at the Theater in Coburg, the hometown of the von Horsts, in February 1925. As the New York Herald reported in an article entitled “American Woman Wins Distinction of Having Operetta Staged in Berlin”:

“before an audience composed chiefly of former and potential rulers, among them Ex-Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, the former Grand-Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Grand Duke Cyril Vladimirovich and other one-time potentates who have established their courts there while waiting for more propitious days.

The work was assured of a friendly reception in Coburg as the von Horsts have social entrée to this circle, but Berlin, it was realized, was quite a different proposition. The proof of the pudding, however, is in the eating, and the invited audience filling the historical old Thalia Theatre form pit to gallery showed unmistakable signs of approval by reacting spontaneously and continuously to the humorous situations of the book and the sprightly and well-achieved score.”

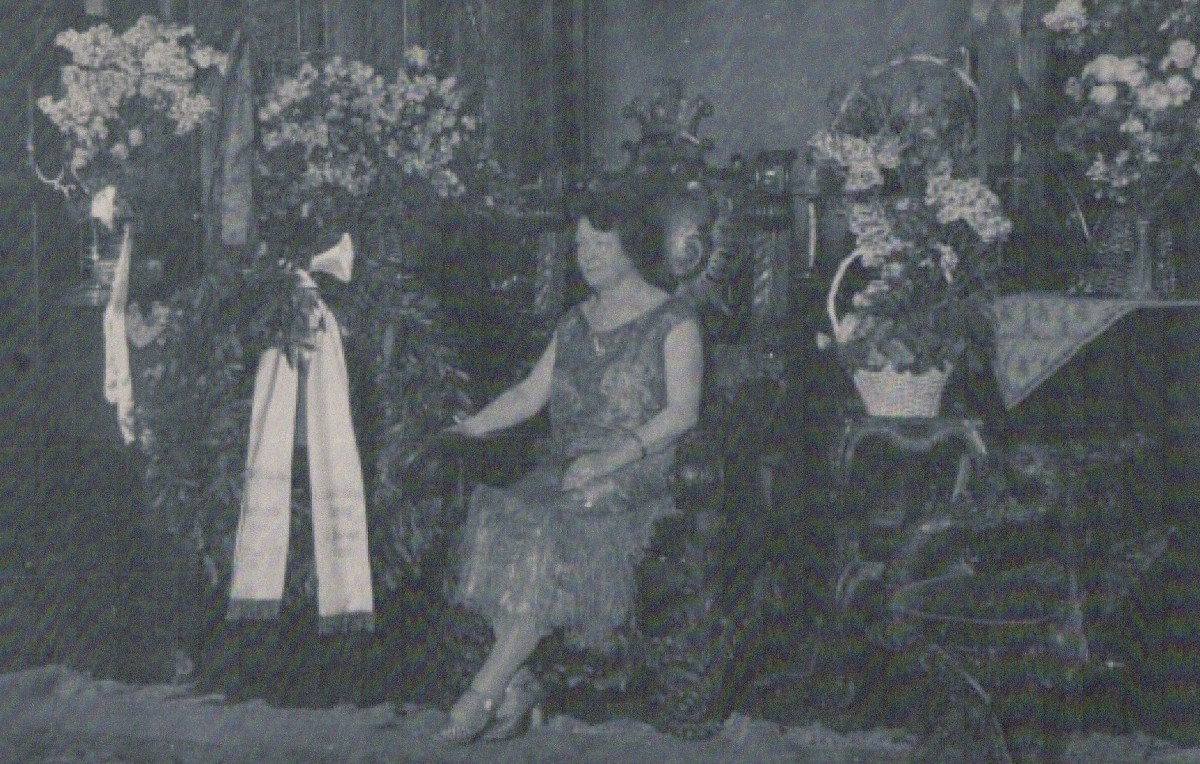

Carita von Horst at the first night party of “Kavalier Jack” in Coburg. (Photo: Archive von Horst family

There is a belief in the family of the composer that the production of the operetta might have been financed with money from the sale of Dwight J. Partello’s violin collection after his death in 1920. He had planned to leave his collection to the Smithsonian Institution but his daughters, Carita and Adeline, who had expected to receive the collection, decided to contest the will. Dwight Partello’s testament was in order, though, and so Adeline and her husband, Arthur M. Abell, who was a music critic, decided to try and convince the Smithsonian that accepting the collection was not in the public good.

They enlisted the help of famous musicians such as Fritz Kreisler, Leopold Stokowski and Arturo Toscanini, who all wrote letters expressing their opposition to the idea that these rare instruments should be lost to musicians forever. The controversy continued for months, but in the end Carita and Adeline did inherit their father’s collection – and sold it to Lyon & Healy in Chicago.

Carita von Horst surrounded by flowers, on the opening night of “Kavalier Jack.” (Photo: Archive von Horst family)

The New York Herald article continues with the review of the premiere at the Thalia Theater in Berlin:

“That the Baroness has exceptional facility in handling an orchestral score became evident two years ago when she gave a concert of her songs and excerpts of an opera in the Beethoven Hall.

Following the trend of the time, she now presents herself as an operetta composer, with Cavalier Jack, first cousin to ‘Raffles’, the formerly popular gentleman thief, as the name hero. And curiously enough, Erich Poremski, the lyric tenor who played the part, bore an unmistakable likeness to the late Harry Walden, a matinée hero who created the “Raffles’ known to Berlin theatre-goers.

Indeed, the pains taken by Dr. Martin Zickel, one of the old guard of Berlin managers, to provide an adequate cast for the von Horst operetta, and his preparation to move the work to one of the West End houses seems to indicate that he has faith in its drawing power.

By a stroke of inspiration he engaged Josefine Dora, one of the few really good women comediennes, whose couplet ‘Am I right?’ proved to be the high water mark of the evening.

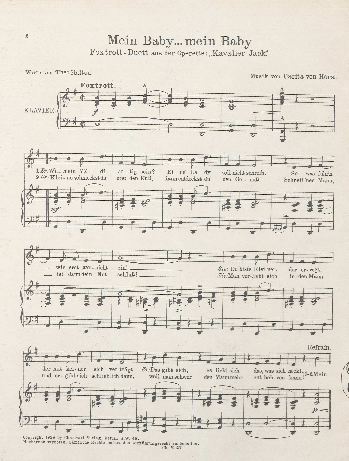

Dance orchestras are also sure to include two of the other hits, ‘My Baby’ and ‘Cavalier Jack,” in their spring itineraries.

Baroness von Horst, with her husband and son, was seated in one of the proscenium boxes, and was surrounded in the entr’actes by her friends, many of them from diplomatic and official German circles. The tulips and other spring blossoms sent to the green room were used to good effect in adding a colorful note to the white and blue English morning room in which the last act of the operetta was set.”

One dance band at least did record tunes from the operetta, Bernard Etté on Vox, but so far it has not been possible to locate a copy.

The song “Heimatlos” from “Kavalier Jack” as published in a sheet music version. (From the music collection of Staatsbibliothek Berlin)

In summer 1926 Kavalier Jack was given in a new production by the Gastspieldirektion Ewald Huth, at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm. Many of the original cast members were the same, the director and choreographer of the dances was Bruno Arno, Siegfried Arno’s younger brother.

The reviews in the Berlin papers were mixed.

The Vossische Zeitung writes on 2 April 1926: “Die Musik […] behauptet sich durch gefällige Wendungen im Melodischen wie durch Geschick der Instrumentation. Frau von Horst wurde nach dem zweiten Akt oft gerufen.”

And Das Kleine Journal states on 4 April 1926:

“Im Thaliatheater gibt es jetzt lustige Abende. Dr. Martin Zickel hat eine Art von Operettenposse herausgebracht, deren zweifellose Wirkung in erster Linie auf sein Konto zu setzen ist. Es ist – wie der Zettel besagt, nach einer amerikanischen Idee – eine kleine Verwechslungs- und Verwandlungskomödie mit detektivischem Einschlag. Das Ganze ist sehr bühnenwirksam gemacht und wird durch eine flotte, treffsichere Regie unterstützt, die auf Schritt und Tritt den alten Praktiker und Routinier Martin Zickel verrät. Zu den wirklich amüsanten und oft spannenden Vorgängen hat eine Dame die Musik geschrieben, Carita von Horst, der hübsche Melodien eingefallen sind und die auch den Versuch macht, eine Art von Finalsätzen zustande zu bringen. Vortrefflich ist die Instrumentation, die auf große Routine schließen läßt. Am Pult sitzt ein Mann, Kapellmeister Perak, der für größere Aufgaben bestimmt zu sein scheint.

Es ist von einer wohlgelungenen, gut abgestimmten Aufführung zu berichten. Man kennt Erich Poremskis degagierte Darstellung der Operettenhelden, erquickt sich an Baselts lebendigem Humor und freut sich über die drastische Komik der Dora. Die schmachtende Lyrikerin vertritt diesmal Elisabeth Balzer-Lichtenstein, die blendend aussieht und echte Operettentragik entwickelt. In weiteren Hauptrollen sieht man noch Heinrich Marlow, der einen düpierten Staatsanwalt mit groteskem Humor gibt, ferner Paul Hansen als lustigen Tippeljungen, den geschmeidigen Krafft-Lortzing als Malerjüngling und endlich die flott tanzende und singende Käthe Lenz. Das Publikum nahm die fröhliche Angelegenheit mit fröhlichem Applaus auf.

The song “Mein Baby” from “Kavalier Jack” as published in a sheet music version. (From the music collection of Staatsbibliothek Berlin)

Nothing is known of any musical activities of Carita von Horst after Kavalier Jack. On 26 April 1935 she died in Meran and was cremated in Milan.

A piano reduction of Kavalier Jack is held by the Library of Congress, and the Library of the University of Alberta, Canada, has a copy of the libretto (“Regiebuch”) of the first production.

After her death, which was reported in Meran as well as in a few US newspapers, she made one posthumous reappearance in an article published in various regional US papers.

The Albuquerque Journal published a text on 10 June 1955 with the sensational title “American Woman, By Misreading Stars, Led Hitler Onto Road That Brought Ruin.”

In the article, one George A. Hensley, retired realtor, and Carita von Horst’s friend for many years, says that after the death of the Baron “his widow remained at Coburg, where she lived quietly under the Weimar Republic, composed operatic music and devoted much time to the study of astrology.”

The article then goes on to say that:

“her astrological predictions, which, more often than not, proved uncannily correct, were brought to Hitler’s attention. Carita von Horst made a profound impression upon Hitler. […]. The gullible Adolf fell for the blandishments of the shrewd Carita, and when failure stared him in the face, the double-dealing American horoscope artist exerted such hypnotic power over him that he returned time and again to her, though she had deliberately bamboozled him in the interests of her native America.”

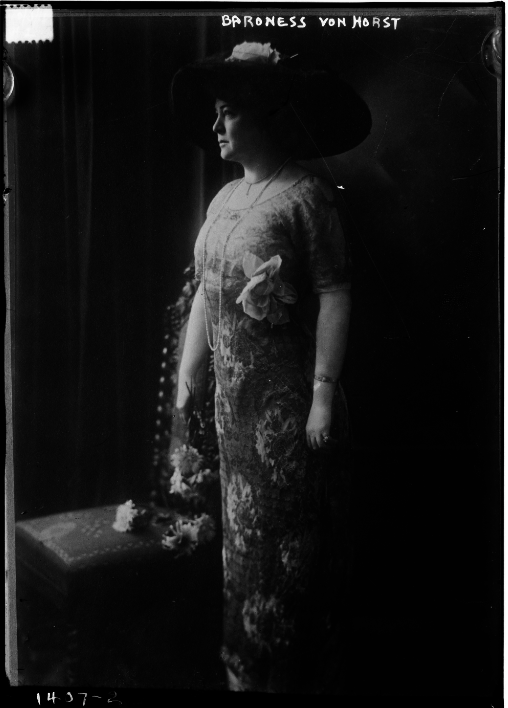

Baroness von Horst, in a portrait from the Library of Congress. (Photo: Archive Thomas Krebs)

The article finishes with a statement by Hensley that he last heard from the Baroness in 1947. This is of course patently untrue, as it was her erstwhile husband, the Baron von Horst, who survived her, dying in 1947. Nor has it been possible to ascertain the ‘fact’ that she was a ‘onetime president of the Astrological Society of Europe’.

The life and career of a composer who took herself seriously, but where solid facts are hard to come by for a researcher had found almost its last echo in a fanciful, sensational newspaper article.

A copy of Vox 08191 has 2 recordings of 2 tunes from “Kavalier Jack”/”Cavalier Jack” made by Bernard Etté’s Orchestra in Berlin between April & May of 1926. The tunes in question are “Komm, Du Kleine Fee”/”Come, little Fairy!” & “Mein Baby”/”My Baby”.

Transfers of both sides are available in Youtube thanks to Youtube user snookerbee:

-”Komm, Du Kleine Fee”/”Come, little Fairy!”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7LSSOJE7Vg

-”Mein Baby”/”My Baby”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YkClTuc4iAA

-

The Smithsonian’s latest Sidedoor podcast has more interesting details on the Abell – Partello controversy – and also contains a rendition of Carita’s “Mein Baby”:

https://www.si.edu/sidedoor/phantom-violins

Hallo Herr Krebs, vielen Dank für den Artikel! Haben Sie genauere Infos zu den beiden “Narren”? In einem Forumsbeitrag habe ich gelesen, dass Sie den Klavierauszug dazu besitzen, wäre es möglich, diesen zu bekommen?

Viele Grüße!

Hallo Laura

Bitte die späte Antwort zu entschuldigen, ich habe sie erst jetzt gesehen. Den Klavierauszug können Sie hier herunterladen:

https://web.tresorit.com/l/yz4nf#etCf4rFRKO0i8OoOQHnMBw

Viele Grüsse