Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

10 November, 2018

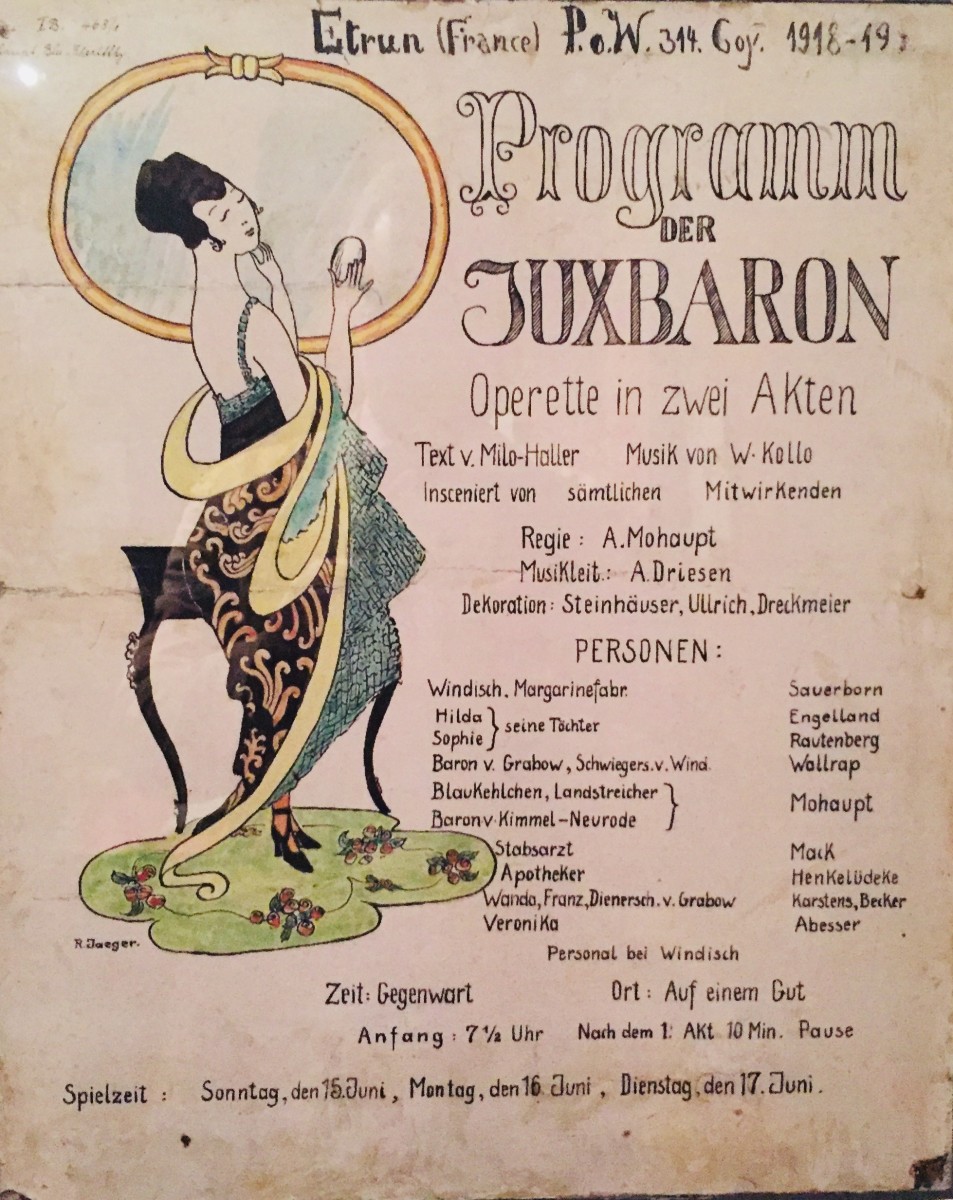

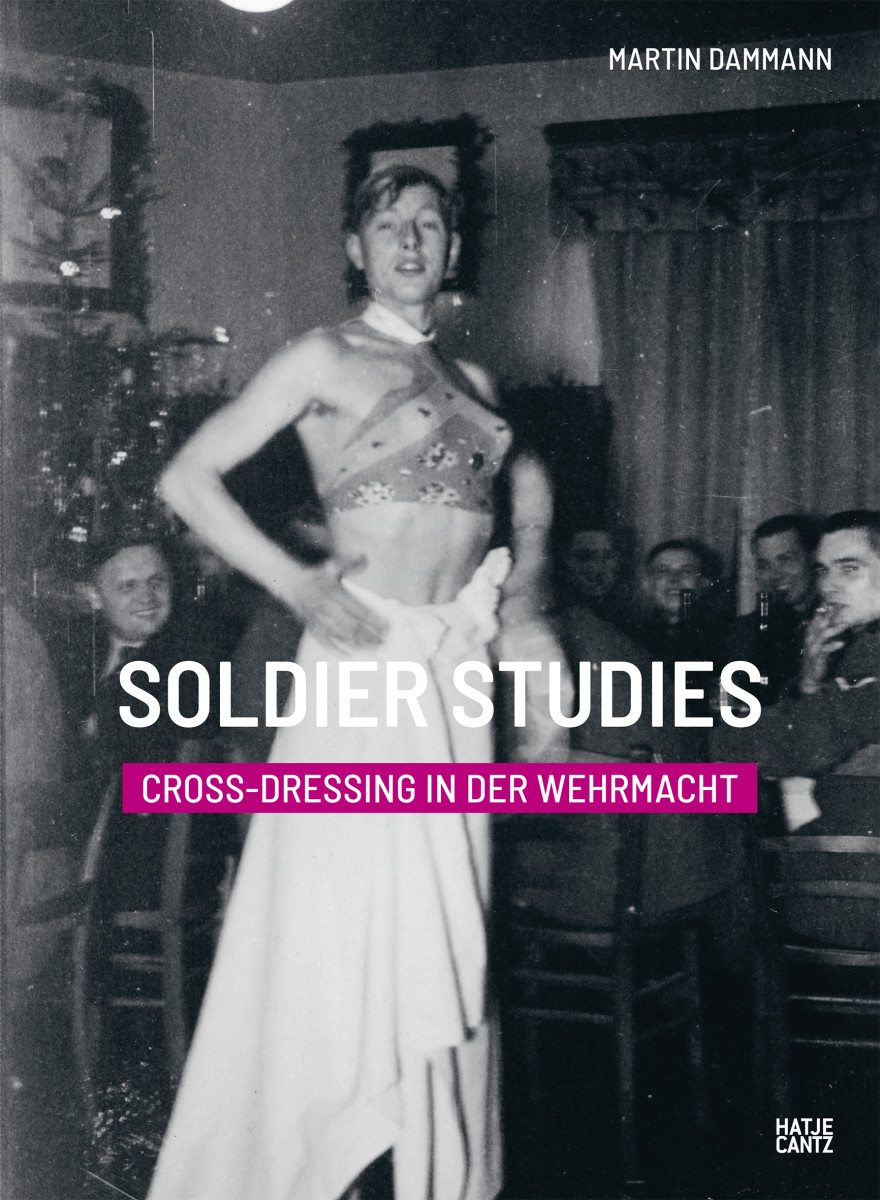

Back in 2014, corresponding with the centenary of the outbreak of World War 1, the Schwules Museum in Berlin offered a magnificent exhibition called Mein Kamerad – Die Diva (‘My Comrade, the Diva’) about theater performances in military prison camps and at the front lines, all of them ‘male only’ with cross-dressed casts, and including operettas from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Gondoliers performed by British officers at Christmas 1917 to Walter Kollo’s Der Juxbaron. Now, this exhibition has been remounted at Theatermuseum Meiningen to coincide with the centenary of the end of WW1. The re-opening of the exhibition also coincides with a new book entitled Soldier Studies: Cross-Dressing in der Wehrmacht by Martin Dammann. It deals with cross-dressed moments in WW2 involving soldiers of the German army.

The “Gondoliers”, Ruhleben, christmas 1917 (Photo: Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library/Schwules Museum)

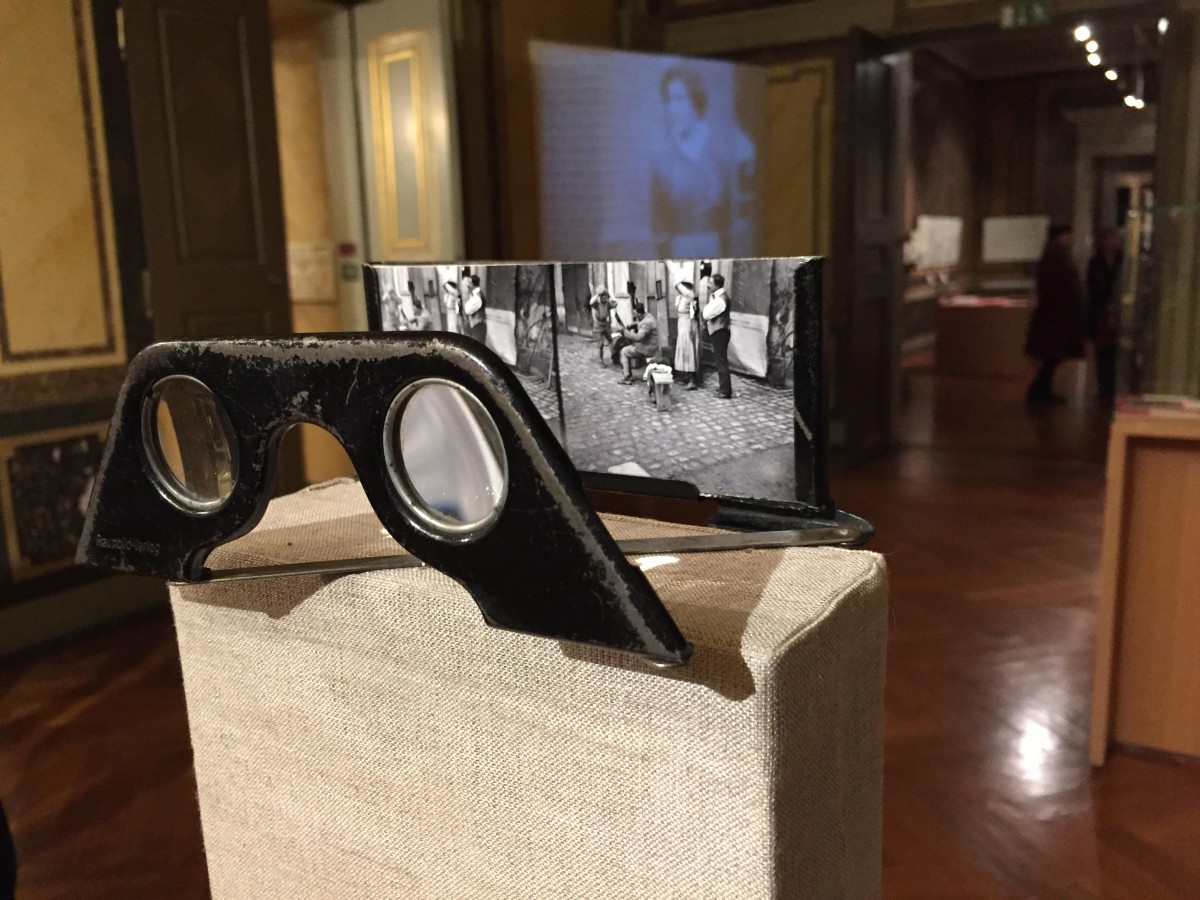

Re-visiting Mein Kamerad – Die Diva four years later is a fascinating experience. Especially because the setting is so different: the objects are now on display at the much larger Meiningen Castle in splendid historical hallways where they are given more space to breathe. Anke Vetter re-curated the show for Meiningen. The various photographs are still outstanding: they show carefree moments of lighthearted entertainment amidst the horrors of war which are swept aside for a few hours by music and over-the-top female impersonators. Seeing the British officers at Ruhleben (near Berlin) in Venetian costumes back in 1917 in The Gondoliers made me wonder why it took almost 100 years for someone like Sasha Regan to come up with comparable all-male Gilbert & Sullivan performances. What happened in the time in between? It’s not as if these cross-dressed performances were secret or unknown, yet they were ignored once life resumed its normal course after 1918. They were certainly ignored by Savoyards and most operetta researchers.

Handmade poster advertising a performance of Walter Kollo’s “Der Juxbaron” in France, June 1919. (Photo: Schwules Museum)

What the exhibition shows, again and again, is how the sexual confusion these cross-dressed performers and performances caused among soldiers were equally suppressed after the end of war. The catalogue cites many love letters expressing lust and longing for the gorgeous men-as-women, describing dreams of sexual encounters. The curator also points out that in many cases the authors of these letters were ashamed of their homosexual longings once they returned to fiancée and family.

English, French and Russian theater performance in a prison war camp in Cottbis (Brandenburg) during World War 1. (Photo: Paul Tharan/Stadtarchiv Cottbus)

But others did not return to ‘normality’ so smoothly. They embarked on a homosexual life that blossomed in the Weimar Republic years, even though §175 still criminalized same-sex activity between men (but not between women). It did so in Germany until 1969; the paragraph wasn’t completely eliminated from law books until 1994.

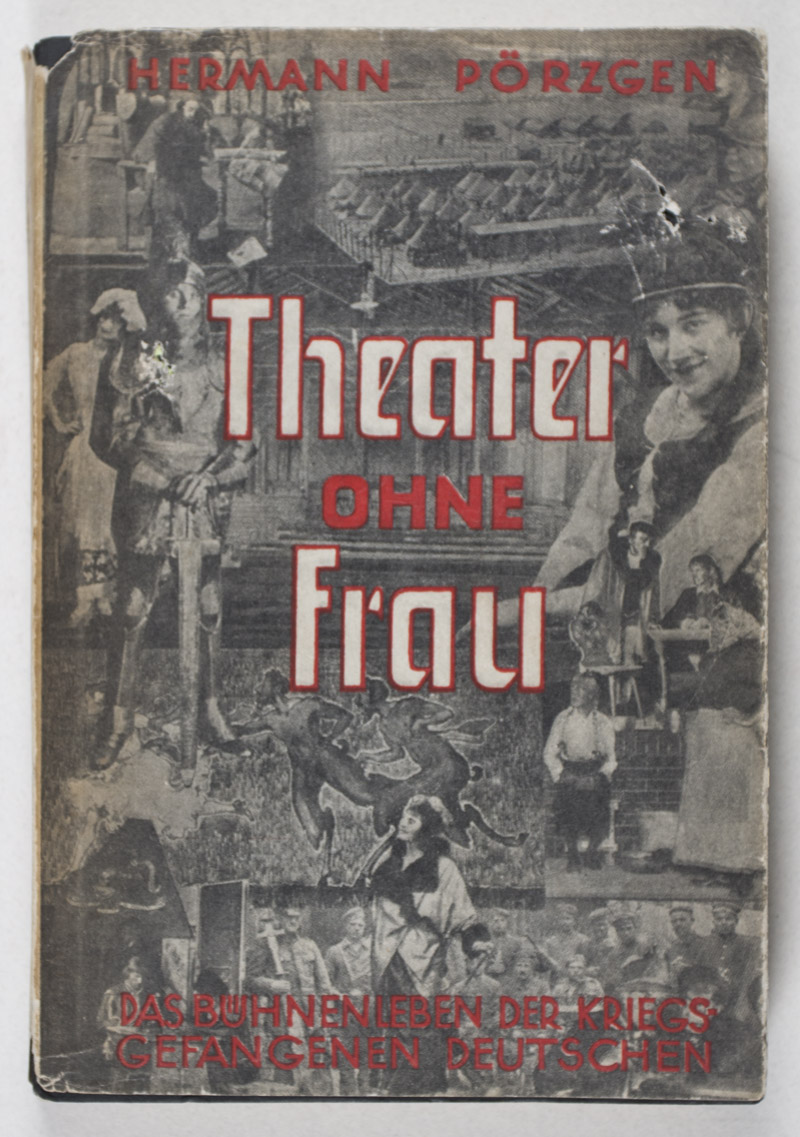

Hermann Pörzgen’s book “Theater ohne Frau: Das Bühnenleben der kriegsgefangenen Deutschen 1914 – 1920.”

In the 1920s theater historians started gathering material about Theater ohne Frau: Das Bühnenleben der kriegsgefangenen Deutschen 1914 – 1920. That’s the famous book by Hermann Pörzgen whose collection of material on WW1 theater performances went to the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung at Schloss Wahn in Cologne. In Meiningen, now, many objects come from that collection. Also, many film clips can be seen, many from French military archives. They show that officers and high ranking military attended such performances, so one must assume that they were common knowledge and approved of. Which is remarkable!

The exhibition “Mein Kamerad – Die Diva” in Meiningen. (Photo: Kevin Clarke)

Seeing the exhibition outside of Schwules Museum, i.e. a gay history venue, doesn’t make the homosexual side immediately obvious. The visitor stumbles across it only after a while when he or she starts reading the text boards in the exhibition. Maybe that’s a good thing. Because when a representative of Schwules Museum spoke about the history of the Berlin-based institution on opening night the local Meiningen audience more or less suffered contortions every time the word ‘gay’ was uttered. (It was a sight to be seen.)

German soldiers performing in World War 1, no details about location and year given. (Photo: Kevin Clarke/ Archive of Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin)

For more details on the homosexual side of the story check out the essay by Jason Crouthamel in the catalogue, entitled “Wir brauchen ganze Männer. Cross-Dressing, Kameradschaft und Homosexualität im deutschen Heer während des Ersten Weltkriegs.” Sadly, the catalogue is in German only. It would be worth creating an English edition. Just like Pörzgen’s book deserves an English edition.

Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies,” 2018. (Photo: Hatje & Cantz)

The 127 page book Soldier Studies, luckily, is in English and German. But it doesn’t contain nearly as much text. There is only a brief intro by Martin Dammann about where he found these photographs from WW2, and a text by Harald Welzer about “The Normality of Military Life.” He discusses the difficult question of how it is possible to have such carefree looking moments of soldier’s life when we know that many of the same men were involved in the most horrific killings and war crimes of the 20th century.

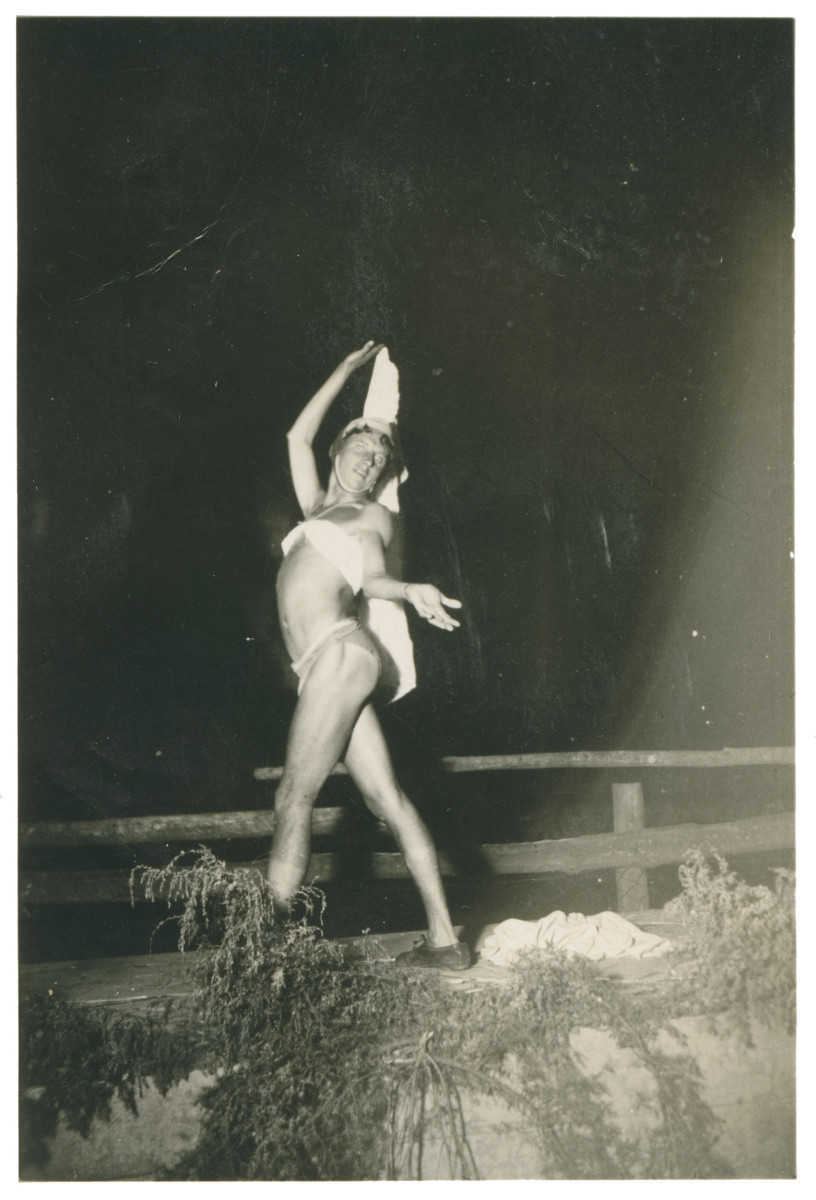

From the chapter “Rekrutenzeit” in Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies.” (Photo: Sammlung Martin Dammann)

In many cases we don’t know who exactly the soldiers are, so it’s anyone’s guess whether they were die-hard Nazis, anti-Semites, whether they cared about politics and Nazi ideology at all, whether they were straight, bisexual, or gay, whether they supported the war or whether they were terrified by and opposed to it? What we also do not know is what shows they performed. In contrast to the images in Mein Kamerad – Die Diva, where we have play bills with titles and casts, here there are only anonymous people with a location given, and a year if you’re lucky.

Some soldiers seem to be putting on a replica of the famous ‘Wunschkonzerte,’ with men dressed up as Rosita Serrano and other famous singers of the time.

From the chapter “Front” in Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies.” (Photo: Sammlung Martin Dammann)

What very much differentiates these ‘operetta’ performances in Soldier Studies from the official productions in theaters and on film is the fact that there are Swastikas and signs of Nazi ideology everywhere. That’s in opposition to Goebbels’ order that operetta should offer no direct ideological infiltration but be a ‘politics free’ zone; at least on the surface. As a result you will not find anyone doing the ‘Hitlergruss’ (the ‘Führer salute’) with the right arm in any operetta film from 1933 to 1945. You will never see flags or obvious Nazi symbolism either in any of these films or stage productions. But you see them here, which makes some of the resurfaced images very rare and interesting.

From the chapter “Unit Celebrations/Kompaniefeste” in Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies.” (Photo: Sammlung Martin Dammann)

Mr. Dammann points out that he found this kind of photographic material regularly in albums he bought on flee-markets; so the photos were not secret and the military authorities must have known about the cross-dressed performances. They tolerated them, it seems, maybe they even encouraged them to allow soldiers time to mentally relax and be more fit for battle?

There are also photos of men hugging and kissing, at a time when Hitler signed a law that ordered immediate execution of anyone engaging in homosexual activity in the military – and certainly within the SS and SA. You can read more about it in Dagmar Herzog’s book Sexuality and German Fascism.

It was post-WW2 society that wanted to forget about such images and actions. Because how could German society face the questions of guilt surrounding the Holocaust and war when there were such party and performance pictures in circulation? It took more than 70 years for someone to overcome the silence and publish the pictures, and ask the obvious questions. It’s a pity that the answers are not longer in this book.

From the chapter “Front” in Martin Dammann’s “Soldier Studies.” (Photo: Sammlung Martin Dammann)

And just for the record: the operetta conference at the University of Leeds in January 2019 will address the topic of Nazi operetta performances too. As far as I am aware this is the first time this will happen in an English language context. It might spark more publications in English.

At Meiningen, one of the most outstanding displays is not a historic image, by the way. Instead, it’s a short video by US-American Infantry Soldiers in Kunar Province, Afghanistan performing Call Me Maybe. It was made by the troops “as a morale boost for our Soldiers here and our families/FRG back home” and is a parody of The Miami Dolphin Cheerleaders performing the same song. It shows how even in very recent military history playing with gender and popular music can created fascinating (and disturbing) results. Truth be told: I find the video more interesting than many recent updated operetta performances. But maybe that’s just me.

For more information about the exhibition in Meiningen, click here.