Kurt Gänzl

Encylopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

In Dahomey was an early American “Negro musical comedy” (in a prologue and 2 acts), one of the first to be written almost entirely by black writers and played entirely by black artists to be presented at a regular Broadway house, rather than the more fringe establishments which normally catered for such shows and their particular audiences. The book was by Jesse A Shipp, lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar and others. Opening night was on 8 September, 1902, at the Grand Opera House in Stamford, Connecticut. Then the show moved to Broadway and premiered on 18 February 1903 at the New York Theater.

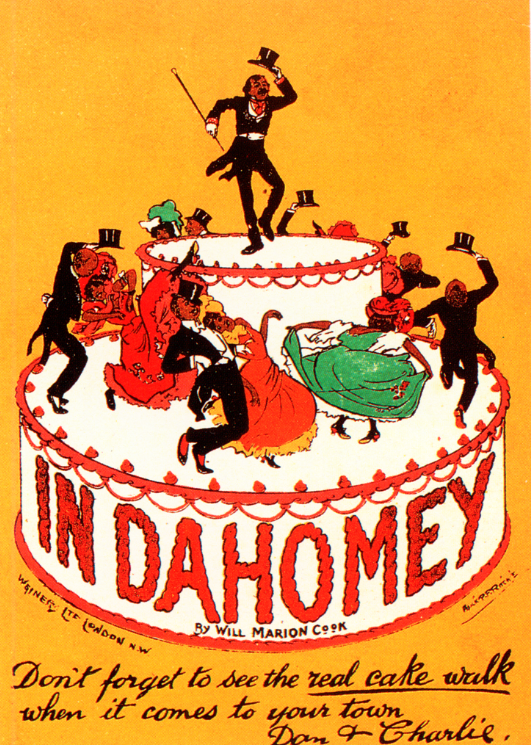

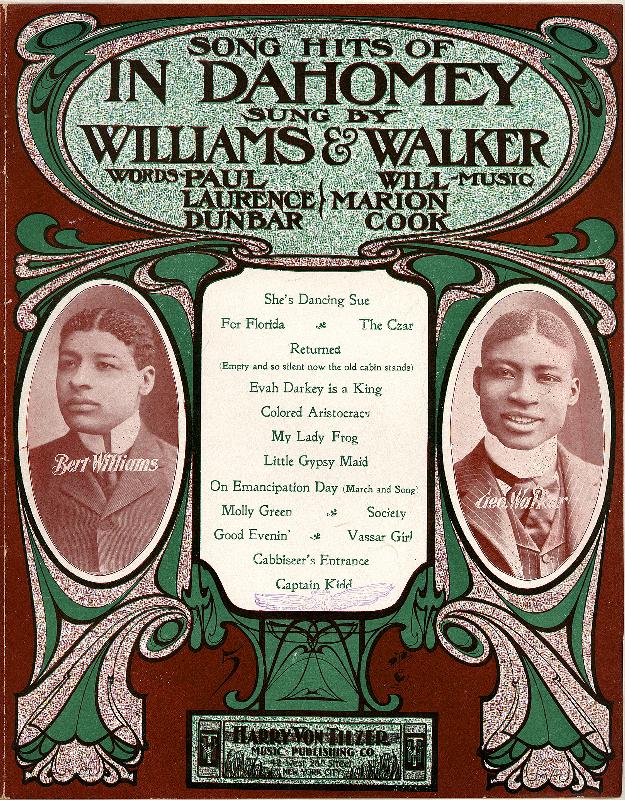

Advertisement for “In Dahomey” when it came to London in 1903. (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

Conceived specifically to feature the popular vaudeville team of Bert Williams and George Walker, its delightfully free-wheeling libretto portrayed the two comedians as the comical Shylock Homestead, known as ‘Shy’ to his friends (Williams), and Rareback Pinkerton, his buddy and adviser (Walker). The two get involved with the Get-the-Coin Syndicate, led by Hustling Charley (played by author Shipp), which is raising cash to back the Dahomey Colonisation Society set up by Hamilton Lightfoot (Peter Hampton) and his brother Moses (William Barker). The idea is to export all the down-and-out blacks of America to a promised land on the African continent. Rareback swindles the money out of the simple Shy, and puts most of it on his own slick back before Nemesis starts to tweak his coat-tails.

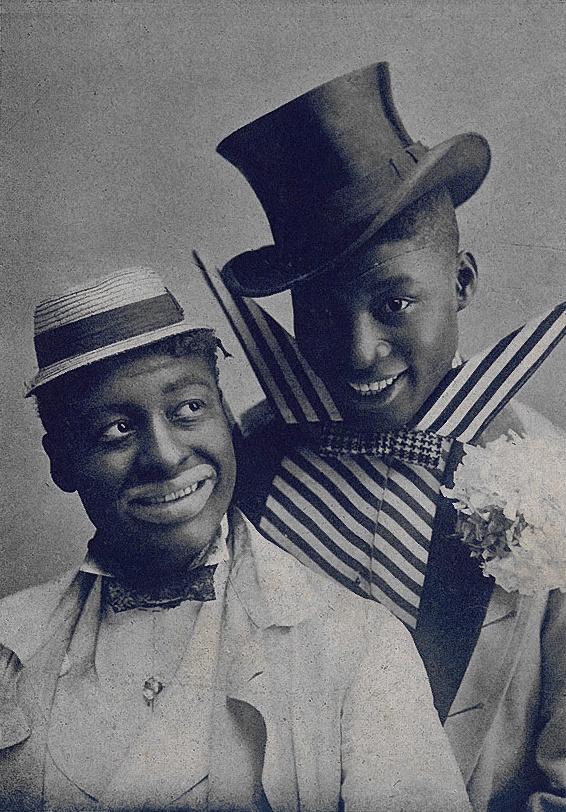

Vaudeville performers Bert Williams (l.) and George Walker in blackface and comic outfits.

The original basic songs of the piece, the majority written by the respected poet Paul Dunbar and composed by Will Marion Cook, featured such pieces as ‘Emancipation Day’ (on which ‘white folk try to pass fo’ coons’), ‘The Czar’ and a song called ‘Society’, with lyrics that sounded like Victorian parlour words, and a well-liked ‘All Goin’ Out, Nothin’ Comin’ In’, but these soon proved insufficient and the score developed as In Dahomey developed out of town. (For more information on Will Marion Cook, click here.)

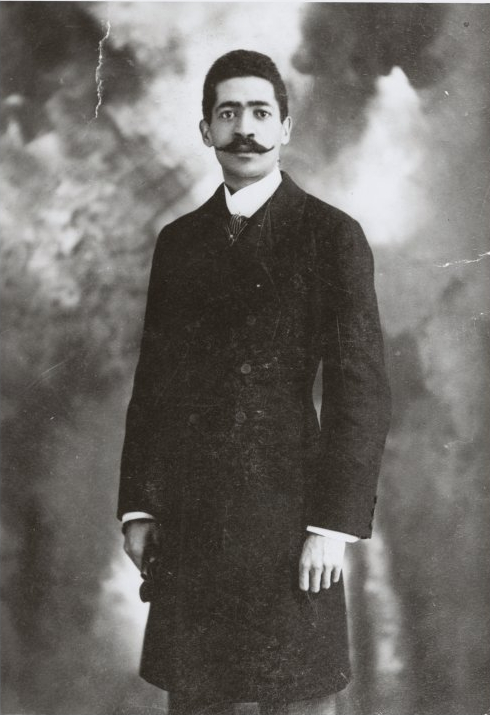

Portrait of composer Will Marion Cook in 1910. (Photo: New York Public Library)

With the help of lyricist Cecil Mack, Cook made over his earlier ‘The Little Gipsy Maid’ to ‘Brown-skinned Baby Mine’, wrote a waltz song ‘Molly Green’, and teamed up with James W Johnson on a piece about the ‘Leader of the Colored Aristocracy’.

That’s How the Cake Walk’s Done

The most effective numbers, however, came from other sources: cast member J. Leubrie Hill and Frank B. Williams’s ‘My Dahomian Queen’, Hill’s later addition explaining catchily ‘That’s How the Cake Walk’s Done’, another cast member, Alex Rogers’s ‘I’m a Jonah Man’ for Williams (added in Chicago four months after opening), and Harry von Tilzer’s infectious ‘I Wants to Be an Actor Lady’ (sung by Aida Overton Walker) and ‘Chocolate Drops’ cakewalk. Williams himself supplied the music for a jig.

The show had, in fact, been originally constructed to tour those variety houses which had specifically black audiences, and an eyebrow or two was raised when producers Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon took the unusual step of opening their show on Broadway. Their gamble did not come off. Williams and Walker were appreciated, but In Dahomey - the lingoistic fun of which seemed altogether on a happier level than much of the music and lyrics – was not considered up to very much as a piece, and the producers could not hold it up in New York for more than 53 performances.

A Genuine Novelty in London

A second gamble, however, did work. The whole cast and production of In Dahomey was promptly shipped to London, where the show opened less than three months after its Broadway première to a very different reaction at the Shaftesbury Theatre on 16 May, 1903.

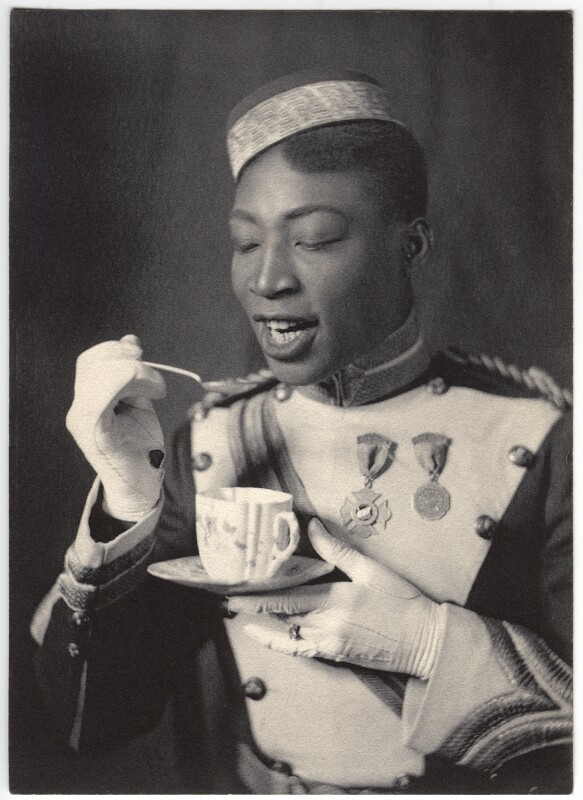

George W. Walker in “In Dahomey”, photographed by Cavendish Morton in 1903. (Photo: National Portrait Gallery)

There, where the nearest thing to a ‘black show’ ever seen was the Christy Minstrels, In Dahomey was a genuine novelty, if nothing else in the unbridled energy with which the black artists played (‘its vitality, quaint comedians, catchy music, and its unique environment should make it one of the dramatic sensations of the London season’).

The hit songs from “In Dahomey.”

The show settled in nicely and, boosted very usefully by a command performance at Buckingham Palace for the young Prince’s birthday celebration (which got the whole royal family up trying the cakewalk which was the raison d’être of the invitation), swelled.

Fifteen extra American blacks were brought across to London to expand the line of the cakewalk dancers, and the cast tasted a kind of theatrical and social success they had never before had through the 251 performances between May and the Boxing Day closure.

Aida Overton Walker and George Walker in “In Dahomey” during the London run, 1903.

Later the piece went on tour in Britain, but ultimately the In Dahomey folk had to go home, and the bubble burst. The show had no tomorrow, and not until the coming of the fashion for ragtime and revue to the international stage did black artists, again Americans, again win such wide attention, either in Britain or America.

Later, in Show Boat (1927), “In Dahomey” was turned into a spectacular Ziegfeld production number during the World Fair section of the show, ensuring that the name at least remained familiar to most Broadway fans.