Richard C. Norton

Operetta Research Center

24 October, 2020

David Monod, professor of American social and cultural history, has undertaken a massive challenge in presenting a history of American vaudeville in six chapters, 226 pages of text. Out of its joyous, incoherent, free market chaos he gives shape, form and order to the rise and fall of this unique form of popular entertainment.

David Monod’s “Vaudeville.” (Photo: The University of North Carolina Press)

Monod distinguishes vaudeville from its 19th century forbears: variety, minstrelsy, dime museums, saloon entertainments. The author defines vaudeville’s appeal as predominantly middle-class, family-appropriate programming with an eye to novelty, surprise, with a constantly changing program. Vaudeville was neither high-brow as grand opera in its European languages, nor as expensive as the legitimate theatre’s operetta, musical comedy or revue. Vaudeville was affordable enough for repeat visits, multiple times a week, and audiences could come and go as they pleased. Vaudeville he says is middle-class and fundamentally democratic.

Entrance to the Grand Theatre presenting “continuous vaudeville” in Buffalo, 1900.

Monod lays out his thesis for vaudeville’s rise and fall over a 35-year period. But this very untidy and un-intellectual subject resists easy categorization. Chapter 1 explores the “Vogue for Vaudeville”, its emergence through urbanity (city centers, neighborhoods), comfort (clean, safe, well-lit theatres) and celebrity (marketing created stars, sold products).

With copious citations from city newspapers and trade journals of the day, Monod offers reviews of performers of every imaginable type. Responsible for one’s own props, costumes, the itinerant life of a vaudeville performer was uneven and unpredictable. Accommodation and travel from town-to-town, venue-to-venue at late hours made for a rough life. Apart from the expected jugglers, acrobats, illusionists, dancers, comics, singers, musicians, quick-change artists, short playlets or sketches, mini-musicals, any craze or novelty that would capture public attention was welcome.

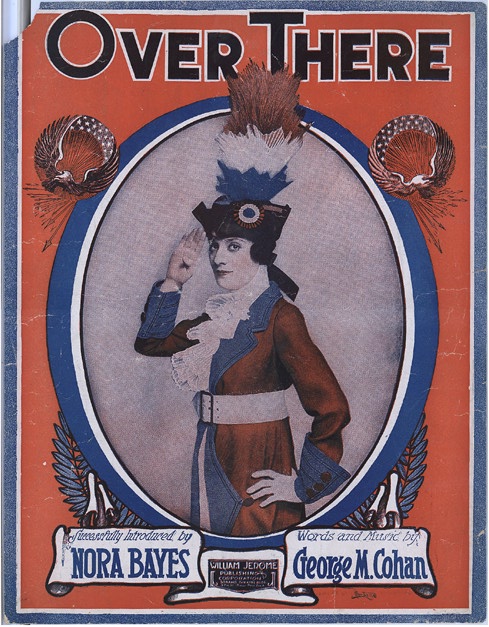

Sophie Tucker, Fannie Brice, Al Jolson, May Irwin, Nora Bayes, Gallagher & Shean, Eddie Cantor, Ray Bolger all honed their craft and skills first in vaudeville, transitioning into musical theatre and back to vaudeville with ease. But most vaudeville performers vanished into obscurity. Celebrities like athlete swimmer and diver Annette Kellerman promoted self-help book for health, Nora Bayes’ photo adorned cigarette packages, while Valeska Surratt endorsed her line of beauty products.

Nora Bayes on the cover of a 1917 sheet music of “Over There” by George M. Cohan.

Yet few African-Americans emerged with lasting success or fame because systemic racism was deeply entrenched, and working conditions so brutal. Monod recounts the struggles of S. H. Dudley and His Smart Set, Bert Williams, Ernest Hogan, Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, among the most celebrated, who crossed over from vaudeville into musical comedy.

Chapter 2 illustrates vaudeville’s modernity, its consumerism, and the variety of its programming. Monod uses the terms naturalism and authenticity to describe how a vaudeville performer engaged the audience. Marketing of American popular song, in particular ragtime, was a major component of vaudeville. Music publishers featured vaudeville performers’ photos on their sheet music covers as a form of celebrity endorsement. Dance crazes such as the two-step, the fox trot, the shimmy, the toddle, the Texas tommy were all promoted or introduced in vaudeville.

Racial stereotyping, ethnic humor and caricature were widely accepted and commonplace in language and terms unacceptable in 2020. The use of blackface among white and African-American performers led to predictable clichés, diminished opportunities for African-Americans trapped by Uncle Tom clichés, ‘negro’ dialect, and rural darkey humor unworthy of their considerable talents

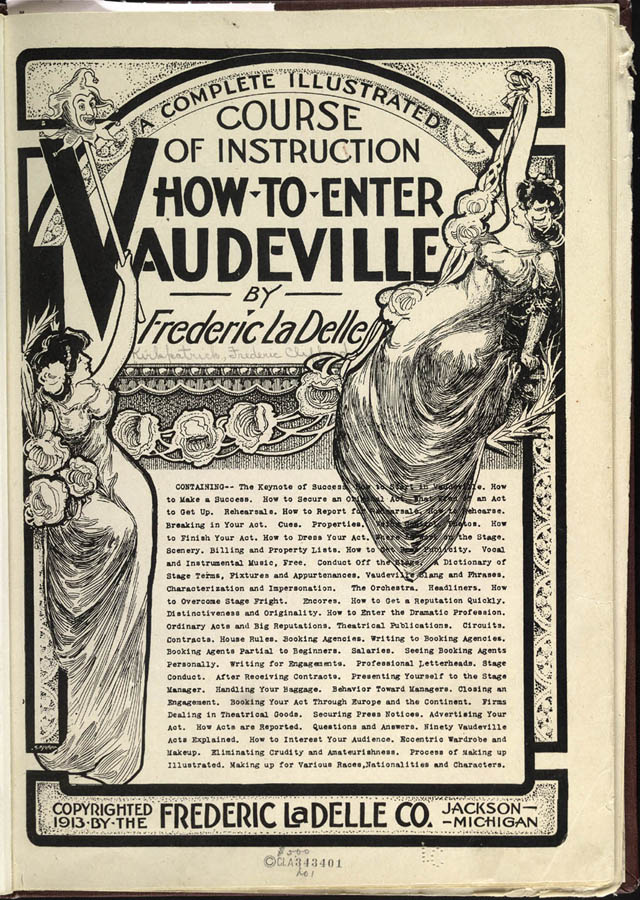

Chapter 3 Monod titles “Grabbing Attention, or Making Good with the Distracted Audience”. If the audience were tired or inattentive, the performer had to win them over. Monod calls this “the direct appeal.”

The singer, celebrity or comic’s confiding in his/her audience, relate a story about his wife/her husband, or what happened the other day, etc. The illusion of intimacy and candor between performer and audience creates a sort of perceived “friendship.” Unlike British music hall where the audience is encouraged to shout back, American vaudeville encouraged its audience to relax, to escape the cares of the workday world.

A 1913 “how-to” booklet for would-be vaudevillians. (Photo: Excelsior Printing Company)

Chapter 4 addresses “Vaudeville Modernism”. If American audiences were slow to accept changes in fashion or style, the endorsement or illustration of a new song, product, dance or device by a vaudeville performer was a necessary step towards popularity. Monod writes “Vaudevillians wanted their acts to appear new.” Tight-waisted dancer/contortionist La Sylphe created a craze for Salome and her veils. The apache dance in which a tough guy tossed the rough girl about proved too wicked for mass vaudeville consumption; it became safe if it could be laughed at. Yet vaudeville struggled to promote its “clean” image; sexual content was scrupulously monitored and controlled, so that women and children would feel secure attending.

Dancer La Sylphe in the early 20th century. (Photo: Dover St. Studio)

Chapters 5 and 6 take an abrupt turn away from vaudeville’s performers and content, to address the business of vaudeville. Small-time vaudeville with its neighborhood theatres, low costs, low prices, is contrasted with the big time vaudeville in big cities, ever higher costs and ticket prices.

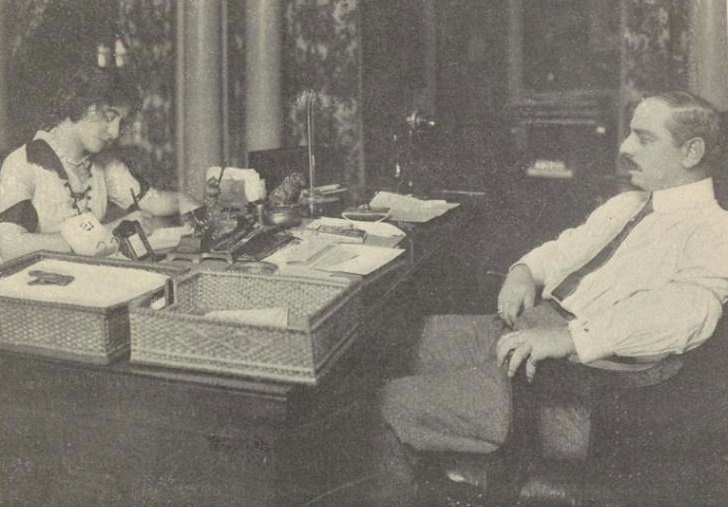

Monod introduces a whole new set of protagonists, the theatre owners (Fred Proctor, H. R. Jacobs, Marcus Loew, Alexander Pantages, Oscar Hammerstein I, B. F. Keith, E. F. Albee) who built vaudeville up with larger luxurious theatres. He faults their predatory business practices, booking agencies, collusion and cartels (UBO or United Booking Office) with the demise of vaudeville.

Marcus Loew transformed vaudeville by creating a vast chain of neighborhood small-time “pop” theaters. Loew pionieered the use of movies to keep down the cost of live entertainment. Here he’s seen in his 42nd Street office, 1914. (Photo: New York Public Library)

Strikes by performers, the creation of unions, the formation of the White Rats, all make for engrossing reading. African-American vaudeville venues and performers were subject to a parallel management cartel, Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), a necessary evil to Afro-American performers who dubbed it ‘tough on black asses.’

The advent of short silent films as one novelty program on the vaudeville bill subsequently led to combination houses where longer films became the main event, and a few vaudeville acts merely preceded or followed the film. Finally, many vaudeville theatres became film houses. Monod explains how predatory business practices combined with the effects of World War I, the emergence of film, new tastes in music all conspired in the death of vaudeville. Prohibition (1919-1933) rates no mention; yet its impact on the café, entertainment, theatre-going life of ordinary Americans is undisputed.

The widespread popularity of radio in the early 1920s overtakes vaudeville. Yet Monod overlooks the impact of electronic sound replacing acoustic recordings in 1926. Not to mention the impact of sound in film (talkies) with The Jazz Singer in 1927.

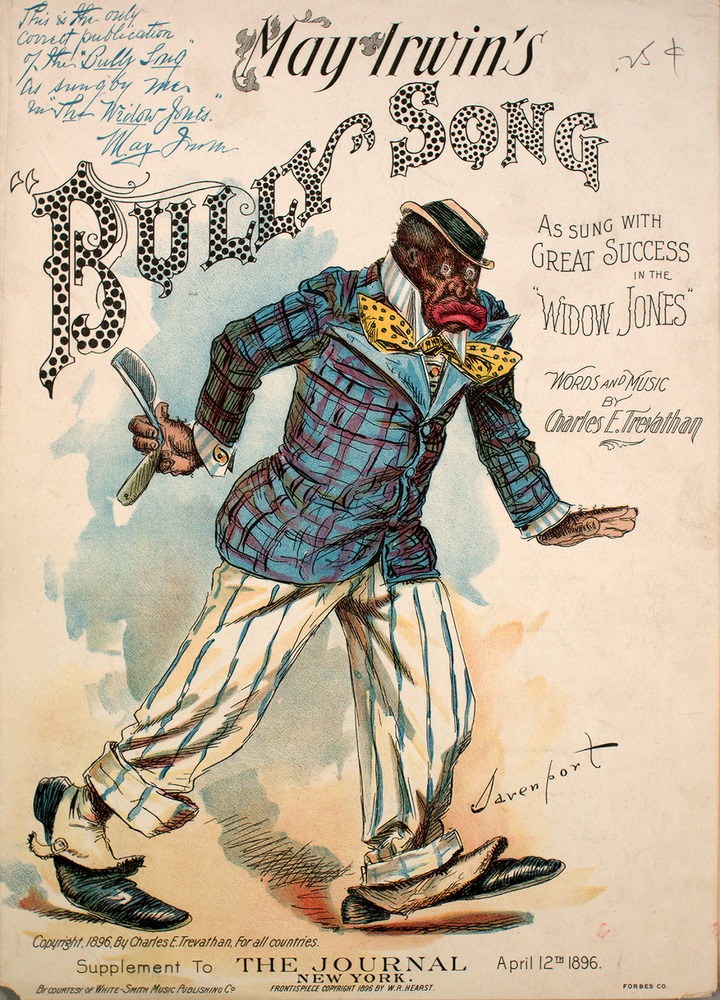

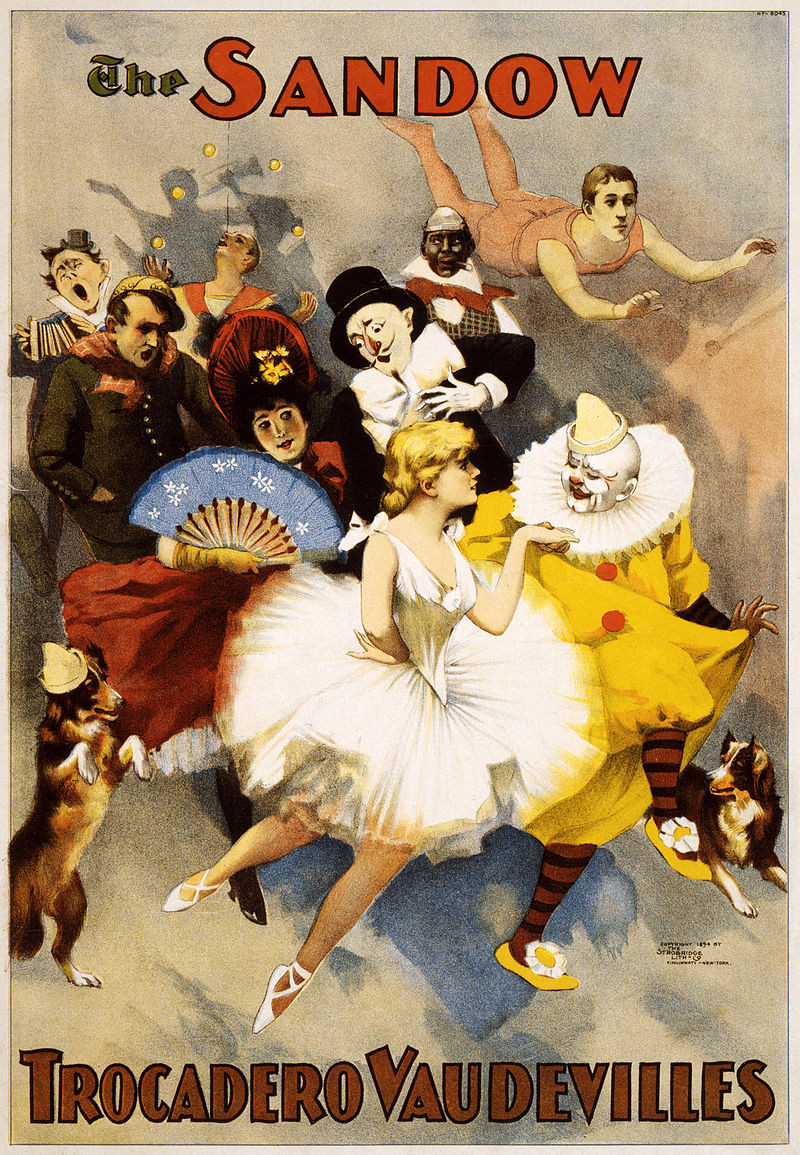

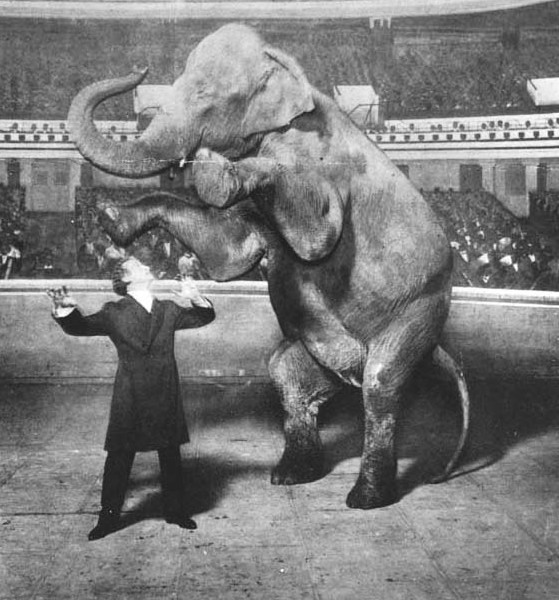

As a serious academic work on a frivolous subject, the volume offers 19 modest yet well-chosen black & white illustrations, plus representative sample vaudeville jokes and several representative song lyrics, like May Irwin’s “Bully Song.”

The “Bully Song” by Charles E. Trevathan from “Widow Jones,” 1896. It documents typical racial stereotypes of the era. Photo: The Journal, New York)

Monod’s book contains a surfeit of detail, whose cumulative effect swamps and drowns the reader. It’s often tempting to take Monod’s citations and footnotes as invitations to search out more about these forgotten vaudeville players on the internet, or in other reference books. Yet the actual experience of observing a typical vaudeville program remains elusive to the modern reader. Few actual programs have survived as so few were printed; most vaudeville houses announced the changing acts on boards at stage right or left, or else verbally.

Poster for the “Sandow Trocadero Vaudevilles,” 1894. (Photo: Strobridge Lithographing Co., Cincinnati & New York)

The author’s passion for his subject is indisputable and infectious. Yet I would have welcomed a lighter, breezier, more generous tone in the writing. Too often David Monod announced his conclusion or chapter thesis, then repeated it again and again in a multitude of ways. The author does not so much arrive at his conclusion, as he does assert it over and over again to make it true.

Harry Houdini and Jennie, the Vanishing Elephant, 1918. (Photo: White Studio)

In the opening acknowledgements, Monod pays tribute to his family members, fellow researchers, students at Wilfrid Laurier University (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) who have assisted him in the preparation of a database accessible to all: vaudevilleamerica.org. Check it out!

Congratulations for all the hard work, I’ll bet the research process was fun. This new volume is welcome for shining a brighter light on a neglected era of American popular culture. We hunger for more.

My grandfather’s mother was Elsie Crescy 1880-1918. She was not married at the time my grandfather was born, 1900, and gave him up to a friend of the Crescy family who adopted him. We’ve never been able to identify with certainty the father of my grandfather but it seems that George W. Monroe is a serious possibility. Elsie was on stage with George W Monroe in Mrs O’Shaughnessey 1899-1900.Would you know of any publications, or other sources such as diaries, that would contain vaudeville “gossip”from 1899-1900? Any suggestions appreciated. Thanks.