Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

The greatest theatrical success of composer Johann Strauss, and the most internationally enduring of all 19th-century Viennese Operetten — the second fact indubitably owing something to the first — Die Fledermaus has come to represent the `golden age’ of the Austrian musical stage to the modern world, much in the same way that Die lustige Witwe has come to represent the `silver age’ of the early 20th century Viennese theatre in the general consciousness.

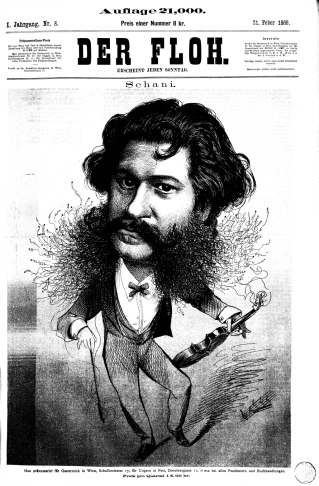

Johann Strauss, as seen by the Viennese newspaper “Der Floh” in 1869.

Like Die lustige Witwe, Die Fledermaus had a libretto based on a French comedy by Henri Meilhac, this time written in conjunction with his habitual partner, Ludovic Halévy, and said to be taken, in its turn, from a German original, Das Gefängnis by Roderich Benedix. Le Réveillon had been produced for the first time at Paris’s Palais-Royal just 18 months prior to the appearance of the Operette, with MM Geoffroy and Mme Reynold appearing as Gabriel and Fanny Gaillardin, from Pincornet-les-Boeufs, and Hyacinthe, the comedian with the famous nose, as Alfred, the chef d’orchestra of the Prince Yermontoff (played in travesty by Georgette Olivier). Alfred tracks his ex-beloved, Fanny, to her provincial home and persists in serenading her with a violin fantasy from La Favorita whilst awaiting her husband’s condemnation to prison for insulting a garde-champêtre, before getting closer. Pellerin was Duparquet, the friend whom Gaillardin once stranded after a masked ball, still ridiculously dressed in a bluebird costume, and who now persuades him to postpone prison for a night out at the Prince’s pavilion in the company of some pretty actresses from Paris. He is, in reality, plotting his revenge. Lheritier played the prison governor, Tourillon, off in an aristocratic disguise to the same party.

Following the Palais-Royal production, Maximilian Steiner, co-director of the Theater an der Wien, ordered a German translation from the veteran playwright Carl Haffner.

He did not judge the result worth producing, but subsequently he — or music publisher Gustave Lewy — had the idea of making a musical libretto from the piece instead, and he handed Haffner’s version over to house-composer and adapter Richard Genée. Genée was apparently no more fond of Haffner’s version than Steiner, and he later asserted that nothing of that first adaptation remained in the final text of Die Fledermaus. However, so as not to offend the old playwright (who died in 1876), he agreed that his name should remain on the playbills. The libretto of Die Fledermaus contained one major alteration to the text of Le Réveillon (which, in other places, in spite of Genée’s assertion, it followed virtually line for line) — it introduced two major female rôles into a play which had been an almost wholly masculine affair. An Operette, and certainly one written for a theatre whose co-director was none other than the great Marie Geistinger, could not manage without its prima donna and its soubrette. Le Réveillon‘s Fanny and her maid are not seen again after the first act. The gambolling of Gaillardin at the ball, and the little episode of the chiming watch, were in the play directed on to one farmer’s girl/actress, Métella, whilst the centrepiece of the third act is a long and highly comical scene between the imprisoned Alfred and Gaillardin, who comes there disguised as a lawyer in order to get to see the man who has been arrested in a compromising situation with his wife.

Die Fledermaus‘s Viennese Rosalinde (Marie Geistinger) is wooed by an Alfred who is a throbbing vocalist rather than a chef d’orchestre but who, like his predecessor, is bundled off to prison in place of her legitimate husband, Gabriel Eisenstein (Jani Szíka).

Marie Geistinger as Offenbach’s Helena, one of her greatest theatrical triumphs.

When Eisenstein turns up at the ball chez Prince Orlofsky (Irma Nittinger), he is enchanted not only by the actress Olga — who is his own maid, Adele (Karoline Charles-Hirsch), in disguise — but by a mysterious Hungarian countess who woos his watch from him. The countess is Rosalinde. After their merry evening, Eisenstein and Frank, the prison governor (Carl Adolf Friese), end up facing each other at the jail with their night’s disguises torn away, and the confrontation with the `false’ Eisenstein takes place, before Rosalinde puts the cap on things by producing the watch she wooed from her husband, and Falke (Ferdinand Lebrecht) reveals that the whole thing has been a set-up. As in the play, the final act opened with a low-comedy scena for a tipsy jailer.

If the libretto replaced many of the subtleties and comicalities of the play with more conventional and well-used elements, it did, nevertheless, produce two fine — if not particularly original — leading lady’s rôles, as well as many a chance for music. Strauss, to whom the libretto was given for setting, took fine and full advantage of them. Geistinger was well-served, with a showpiece csárdás (`Klänge der Heimat’) in which to prove her Hungarianness, and paired with Eisenstein in a delicious sung version of the watch-scene (`Dieser Anstand, so manierlich’), whilst the soubrette had two showy coloratura pieces, a mocking laughing song (`Mein Herr Marquis’) reproving the disguised Eisenstein for mistaking her for a ladies’ maid, and a tacked-in ariette à tiroirs (`Spiel’ ich die Unschuld vom Lande’), allowing Adele to show off her range as she demonstrates her suitability for a stage career. The bored Orlofsky summoned his guests to enjoy themselves in a loping mezzo-soprano `Ich lade gern mir Gäste ein’. The men were less showily served, although Falke led a swaying hymn to brotherly love in `Bruderlein und Schwesterlein’ and Alfred indulged in some operatic extravagances as well as an intimate supper-table duet with the almost errant wife (`Trinke, liebchen, trinke schnell’). Orlofsky’s party also provided the opportunity for a display of dancing.

Many myths have grown up around the show and its original success or non-success, particularly in Vienna. The truth is that Die Fledermaus was well — if not extravagantly — received, and, like virtually all Strauss’s pieces, good, bad and ikndifferent, was quickly taken up to be mounted in other Austrian, German and German-language houses where his name was a sure draw. In Vienna, it was played 45 times in repertoire before the summer break, and was brought back again in 1875 and in 1876, reaching its 100th performance on 17 October 1876 with Frlns Meinhardt (Rosalinde) and Steinherr (Adele) featured alongside Szíka, Alexander Girardi (Falke) and Felix Schweighofer (Frank). Thereafter it remained fairly steadily in the repertoire at the Theater an der Wien, good for a regular number of performances in most years, reaching its 200th performance 15 May 1888 and the 300th on 9 December 1899. If the original run, within the repertoire system, had been less stunning than the show’s later reputation might have suggested, and indeed far from the record compiled by such pieces as Die schöne Helena at the same house, its initial showing was above average and its (not unbroken) longevity in the repertoire exceptional. Carl Streitmann, Phila Wolff and Gerda Walde featured in a new production in 1905 (1 April), and the piece was seen at other theatres including the Hofoper, at the Volksoper for the first time in 1907, the Raimundtheater in 1908, the Johann Strauss-Theater in 1911 and the Bürgertheater in 1916, making up part of the repertoire of any self-respecting Operette theater in Vienna in the same way that it did in the provinces. Amongst the memorable Viennese Fledermaus productions of later years was one at the Staatsoper in 1960 which featured Hilde Güden (Rosalinde), Rita Streich (Adele) and Eberhard Wächter (Eisenstein).

The Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater in Berlin.

In Berlin, the show was produced at the Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater with a singular success which allegedly gave a boost to its reputation back in Vienna. The 200th performance was passed within two years of the first, and Die Fledermaus went on to become the most popular Operette of the 19th century on German stages. Budapest also saw its first performance of the show in German, as did New York when the Stadt Theater mounted the piece just seven months after the Viennese première with Lina Mayr (Rosalinde), Ferdinand Schütz (Eisenstein), Schönwolff (Frank) and Antonie Heynold (Adele), but neither city proved in much haste to provide a vernacular version. It was eight years before the Hungarian capital saw an Hungarian-language production, and, although the piece got regular showings in New York’s German theatres — including an 1881 season with Geistinger starred in her original rôle alongside Mathilde Cottrelly (Adele) and Max Schnelle (Eisenstein) — it was over a decade before New Yorkers got Die Fledermaus in an English translation.

The first English-language version was mounted on the vast stage of London’s Alhambra Theatre (ad Hamilton Aidé) as a Christmas entertainment for the 1876-7 season with a cast headed by Cora Cabella, Kate Munroe, Adelaide Newton, Guillaume Loredan, Edmund Rosenthal and J H Jarvis. It ran for a sufficient season of some four months, and encouraged the theatre to try Strauss’s earlier Indigo the following Christmas, but — although a performance of the original version was given at the Royalty Theatre in January 1895 by a touring German company — it was more than 30 years after this before another English Fledermaus was seen in the city. The following October, Australia was given its first glimpse of the show, under the aegis of Martin Simonsen’s company (and billed, with typical local mendacity, as having been played 500 nights at the Alhambra) at Sydney’s Queen’s Theatre. Fannie Simonsen was Rosalind and Henry Bracy Eisenstein with Minna Fischer (Adele), Maud Walton (Orlofsky), Henry Hod[g]son (Frank) and G Johnson (Falke) in support. The company left town after ten days.

Boston (which had already seen versions of Le Réveillon as The Christmas Supper (ad Fred Williams, George A Ernst 24 March 1873, and On Bail ad W S Gilbert) got America’s first English-language Fledermaus, under the clever title The Lark, in March 1880.

The piece had been re-set in America by adaptors Nat Childs and F S Harris, and since the Boston management were aggrieved over the idea of composer Strauss wishing actually to be paid for the use of his orchestrations, local m.d. John Braham stuck his own under the published melody-lines of the 17 pieces of Strauss used for the occasion. J B Mason and Rose Temple played Harold and Lillian Allison, who were Boston’s equivalent of the Eisensteins, and Alice Carle was Bessie Dooling, ie Adele. This version was later seen at San Francisco’s Tivoli Opera House (July 1880). New York’s first English Die Fledermaus (ad Sydney Rosenfeld .. ‘if Mr Rosenfeld cannot turn out better work than this he should retire from the field..’) was only mounted by John McCaull at the Casino Theater, after a Philadelphia run-in, some five years further down the line, with Mme Cottrelly now playing her Adele in English alongside Rosalba Beecher (Rosalinde), Mark Smith (Eisenstein) and De Wolf Hopper (Frank), It was voted ‘a mild failure’ but, after the split between McCaull and the Casino management, it was repeated later the same season at Wallack’s Theater (14 September 1886) before, as in England, going on the shelf for several decades.

Hungary’s first vernacular Denevér was mounted not in Budapest but at Kolozsvár with Sarolta Krecsányi and Béla Szombathelyi featured. It was played at Szeged the following year, and only in 1882 did a version (ad Lajos Evva) arrive in Budapest. Aranka Hegyi was the first Budapest Rosalinde with Mariska Komáromi (Ghita, ex-Adele), Elek Solymossy (Bussola), Vidor Kassai (Fujo), Pál Vidor (Crapotti) and János Kápolnai (Ritenuto, ex-Alfred) in the other major rôles. It played 54 times and was revived in 1891 (24 January) and 1907 (22 October) before going on to productions at the Népopera (1912, 1915), the Városi Színház (1926) and other houses as, in line with the rest of the world, it worked its way up past more immediately popular pieces into its present-day place at the peak of popularity. It was most recently seen in Budapest at the Erkel Szinház in 1992 (31 December) in an adaptation by Agnes Romhányi and in 1997 (20 December) in a version by Sándor Fischer.

Italy, Sweden, Russia, the Netherlands and Switzerland all took in Die Fledermaus in the first years after its début, but it was France which took the longest time to catch up with the show, and, according to one variation of the story, not without reason.

In those slap-happy copyright days, nobody in Vienna, apparently, had bothered to ask Meilhac and Halévy for permission to make a musical out of their play. So producer Victor Koning called on authors Alfred Delecour and Victor Wilder who had, to Strauss’s satisfaction, heavily rewritten the libretto of Indigo for France, and ordered a brand new script to be written around some portions of Strauss’s score.

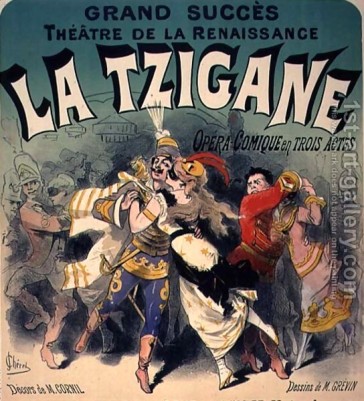

A poster advertising the original French adaptation of “Die Fledermaus” starring Zulmar Bouffar.

The story they used was a well-worn one, featuring a womanizing Prince, wed by necessity and by procuration, who goes out gallivanting with some bohemiennes on the day of his marriage. His bride-to-be gets herself into gypsy gear, seeks him out, and tames him. If the story was familiar, the score was less so. Many favourite pages of Die Fledermaus were missing. There was no csárdás, no Orlofsky’s song, no Audition couplets and the bits that remained, often uncomfortably tacked one to another, were topped up with Lorenza Feliciana’s valse brilliante `O süsses Wörtchen’ (pasted onto a Fledermaus melody) and `Zigeunerkind wie glänzt dein Haar’ (`Pourquoi pleurer’) from Cagliostro in Wien and some other spare and written-for-the-occasion Strauss music. La Tzigane, with Zulma Bouffar as Princess Arabelle, the baritone Ismaël (who garnered both the `Bruderlein’ and `Trincke liebchen’ melodies as solos) as the naughty Prince, and Berthelier, Urbain and Léa d’Asco featured, was equipped with one of the most luxurious stagings Koning’s theatre had ever provided. However, although the show emerged as an uncomfortable paste-up job, with Strauss himself on hand to win masses of journalistic space, it nevertheless managed 63-plus performances before Koning replaced it with the première of Le Petit Duc. La Tsigane was only seen again when a German version of it (ad Hans Weigel, additional music Max Schönherr) was for some reason mounted at Graz in 1985 (16 November).

It was 1904 before a regular La Chauve-Souris (ad Paul Ferrier) was seen in Paris. Fernand Samuel’s production at the Variétés featured Albert Brasseur and Max Dearly as Gaillardin and Tourillon (since the action was reset in France, the names from Le Réveillon had been resurrected for this pair), with Cécile Thévenet (Caroline, ex-Rosalinde), Jane Saulier (Arlette, ex-Adele) and Ève Lavallière as Orlofsky. It was played 56 times. However, late though this production may have been, it was still too soon. The lawsuits flew, and the heirs of not Meilhac or Halévy but of .. Victor Wilder were awarded 50% of the royalties on La Chauve-Souris and 3,000 francs in damages by the Tribunal de la Seine. On the grounds of his authorship of La Tzigane!

Die Fledermaus was still, even in the early days of 20th century, far from the all-obscuring international favourite it was to become, but it was a regular part of the repertoire in, in particular, German-speaking countries where it had been integrated into the repertoire of such houses as the Berlin Opera (8 May 1899).

In 1905 it was produced at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in German with Marcella Sembrich and Andreas Dippel featured, and in 1910 (4 July) a new English version (ad Armand Kalisch) starring Carrie Tubb, Joseph O’Mara and Frederick Ranalow was played by Thomas Beecham’s company at London’s Her Majesty’s Theatre in the pro-Viennese atmosphere engendered by The Merry Widow and its successors. The following year, yet another anglicized Fledermaus (ad Gladys Unger, Arthur Anderson) was produced at London’s Lyric Theatre under the title Nightbirds with C H Workman and Constance Drever, Paris’s Veuve joyeuse, starred for 138 performances. This version was picked up for Broadway and played with José Collins, Claude Flemming and Maurice Farkoa, one of the Dolly Sisters as Adele (the girls interpolated their turn into the proceedings) and the addition of Arthur Gutman and Joseph H McKeon’s ‘Must We Say Goodbye?’ and a duo for a couple of prison warders made out of the ‘Blue Danube’ to Strauss’s score, as The Merry Countess (20 August 1912, Casino Theater).

Korngold at the piano, 1929.

Another round of productions was set off by Max Reinhardt’s typically big and typically botched Berlin production of 1929 (Deutsches Theater 8 June). Hermann Thimig, Maria Rajdl, Adele Kern and Oscar Karlweis as a non-travesty Orlofsky were featured in a lavishly staged version which purported to have gone back to Le Réveillon for its text (ad Karl Rossler, Marcellus Schiffer) … but which nevertheless did not leave Rosalinde and Adele at home for the second and third acts! The version’s vanities included some additional lyrics by Schiffer glorifying Reinhardt, whilst Strauss’s music had been `improved’ by E W Korngold. The Paris Théâtre Pigalle (5 October 1929 ad Nino) played Reinhardt’s version with Lotte Schöne, Jarmila Novotna, Dorville and Roger Tréville featured, whilst the Shuberts had Fanny Todd Mitchell do a version, which claimed with equal lack of veracity to be a version of Le Réveillon and which, as A Wonderful Night (31 October 1929), played 125 Broadway performances with, of course, its leading ladies well and truly intact..

London’s Royal Opera House gave a faithful Fledermaus in 1930 (14 May) with Willi Wörle, Lotte Lehmann, Gerhard Hüsch and Elisabeth Schumann, whilst another American version (ad Alan Child, Robert A Simon) arrived in 1933 (14 October) with Peggy Wood (Rosalinde), Helen Ford (Adele) and John Hazzard as Frosch, to add a further 115 performances to Die Fledermaus‘s bitty Broadway record, before the Reinhardt/Korngold version turned up, on the wings of the war, for its Broadway season under the title Rosalinda (44th Street Theater 28 October 1942). Dorothy Sarnoff took the title-rôle, whilst Karlweis repeated his Berlin Orlofsky and Korngold conducted ‘his’ music, and Rosalinda — if scarcely Die Fledermaus — proved a perfect piece of good-old-days, richly produced wartime entertainment through 521 performances. London promptly followed up, and Tom Arnold and Bernard Delfont presented Gay Rosalinda (ad Austin Melford, Rudolf Bernauer, Sam Heppner 8 March 1945) at the Palace Theatre with Cyril Ritchard and Ruth Naylor featured and Richard Tauber conducting. The success was repeated for 413 London performances.

Since this late and unexpected burst of commercial theatre success for more or less botched versions of Die Fledermaus, the show has largely retreated — in normally less tampered-with shape — into the opera houses of those countries which do not sport repertoire Operette companies.

Covent Garden, the Metropolitan (ad Howard Dietz, then ad Betty Comden, Adolph Green), the Berlin and Vienna Opera Houses, and the Paris Opera have all hosted the show, and divas of the ilk of Joan Sutherland and Kiri te Kanawa have played Rosalinde. Some of the lightness and gaiety which was the chief attraction of the commercial version has unavoidably been lost in this re-housing of what is basically a musical-comedy piece but, whilst Suppé, Millöcker and Zeller are forgotten, the waltz king’s most popular work has become in the process regarded as the one `safe’ 19th-century Viennese Operette for the world’s 20th-century operatic houses. Even in bitterly butchered shapes. Thus, more than a century after its première, Die Fledermaus is going more strongly than ever, with an international production rate that only the favourite works of Offenbach and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado among 19th-century works can come near.

The poster for the film version “Oh Rosalinda”.

Versions of Die Fledermaus have been put on film on a number of occasions in the German language — in 1931 by Carl Lamac with Anny Ondra, Georg Alexander and Ivan Petrovitch, by Paul Verhoven in 1937 with Lidia Baarova and Hans Sohnker, by Géza von Bolvary in 1945 with Marte Harell, Willy Frisch and Johannes Heesters, and in 1962 by Géza von Cziffra with Peter Alexander, Marianne Koch and Marika Rökk. Powell and Pressburger were reponsible for an English-language version (Oh, Rosalinda!) released in 1955 in which Michael Redgrave was paired with Anneliese Rothenberger. The 1931 edition had a French equivalent in which Ms Ondra teamed with Marcelle Denya, Mauricet and Géo Bury. In the days of television and video recordings such operatic names as Gundula Janowitz (1972), Joan Sutherland (Australian Opera 1982 and Royal Opera 1990), Kiri te Kanawa and Herman Prey (Royal Opera, 1983) and Ms te Kanawa again (Metropolitan Opera 1986) have attempted to cross over into Operette. A silent version, with accompanying music, was put out in 1923 in which Lya de Putti and Harry Liedtke featured.

An attempt at a musequel to Die Fledermaus was put out by Leon Treptow (text) and K A Raida (music) at Berlin’s Viktoria Theater in 1882 (8 April) under the title Prinz Orlofsky. In fact, it was not a genuine sequel, telling a wholly conventional and oft-used comic-opera tale and simply tacking the names of the characters of Genée’s Operette on to its characters. Prince Orlofsky pretends he is married and a father to win financial favours from an elderly uncle. The uncle turns up, is gotten drunk for a act of revelry, Adele poses as Mrs Orlofsky and at the end, of course, becomes her for real. Frosch had become the Prince’s butler, Alfred got himself a country lass who had a showy rôle in the second act, and Frank, Eisenstein and Falke put in appearances. Rosalinde had the good sense to stay at home this time.

Germany: Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater 8 July 1874; USA: Stadt Theater (Ger) 21 November 1874, Boston Museum The Lark March 1880, Casino Theater (Eng) 16 March 1885; UK: Alhambra Theatre 18 December 1876; Australia: Queen’s Theatre, Sydney 17 October 1877; Hungary: (Ger) 14 November 1874; Kolozsvár Denevér 19 October 1877, Népszinház, Budapest 25 August 1882; France: Théâtre de la Renaissance La Tzigane 30 October 1877, Théâtre des Variétés La Chauve-Souris 22 April 1904;

Films: Max Mack 1923, Pathé 1931 (Ger and Fr), 1937 (Ger), 1945 (Ger), 1955 Oh, Rosalinda! (Eng) etc.

Recordings: complete (Decca, EMI, RCA, Deutsche Grammophon, HMV, Eurodicsc, Teldec, Teletheater etc), complete in French (Polydor), complete in Hungarian (Qualiton), complete in Russian (MK), complete in English (CBS), complete in Spanish (Montilla) etc