Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

Henri Meilhac’s play L’Attaché d’ambassade, produced at Paris’s Théâtre du Vaudeville in 1861, was not a success. It was played for just 15 performances in the French capital. Yet, in the way of the time, this failure did not affect its export prospects and the piece found its way to the Vienna stage the following year. There, played at the Carltheater in an adaptation by `Alexander Bergen’ as Der Gesandschafts-Attaché, it became not only a success but a piece which was popular enough to win regular revivals over a number of years.

The young Franz Lehár.

The first years of the 20th century in the Viennese musical theatre were not rich in successes. The staple composers of earlier years — Suppé, Strauss, Millöcker — were gone, and the last real new successes which the Theater an der Wien had hosted had been Richard Heuberger’s Der Opernball, a musical version of the French comedy Les Dominos roses, and the young Edmund Eysler’s Bruder Straubinger. It was logical, then, that librettist Victor Léon, the co-author of Der Opernball, should present Theater an der Wien director Karczag with another French-flavoured libretto for Heuberger to set — a musical version of Der Gesandschafts-Attaché. One version of the story goes that Heuberger actually set Léon and Leo Stein’s piece, but that Karczag did not like the score he provided and took back the libretto. On the encouragement of theatre secretary Emil Steininger, he then proposed to offer it to Lehár, whose début piece, Wiener Frauen, had been played at the Theater an der Wien three years earlier. Léon, however, objected. Although he had had a major success with Lehár on Der Rastelbinder at the rival Carltheater, he and Stein had subsequently worked with the composer on the barely successful Der Göttergatte in which the composer had clearly failed to catch the Offenbachian opéra-bouffe flavour the librettists intended their piece to have. But, in the end, he agreed that Lehár should be given the opportunity to set a portion of the piece, as a kind of an audition. When the composer played Léon the melody which he had set to the Hanna/Danilo duet `Dummer, dummer Reitersmann’, the librettist allowed himself to be convinced.

Karczag, however, showed little enthusiasm for the show. During 1905 little had gone right for him.

Star comic Girardi had gone off after the production of Pufferl taking the most promising composer of the time, Edmund Eysler, with him, and if some performances of the second-hand Strauss pastiche Wiener Blut had filled a gap, neither a German version of Huszka’s Bob herceg (10 performances) nor Léon’s collaboration with another young composer, Leo Ascher, on Vergeltsgott (69 performances) had proved a hit. Another essay with an untried composer, Leo Fall’s Der Rebell, had been a total disaster, folding after just five performances. There was little incentive for Karczag to invest heavily in another new piece in which he had little confidence, and so, when Die lustige Witwe was hurriedly produced to fill the gap left by the flop of Der Rebell (in preference, according to Harry B Smith’s memoirs, to De Koven’s Robin Hood, which was also on Karczag’s waiting list), it was done so on the proverbial shoestring with recycled scenery and costumes. Four weeks after the closure of Fall’s Operette, Die lustige Witwe opened.

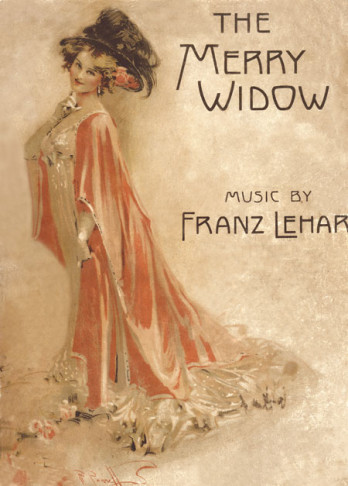

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in London’s “The Merry Widow”, 1907.

Léon and Stein’s piece, which was shyly announced only as being `teilweise nach einer fremden Grundidee’ (partly based on a foreign idea), was set in contemporary Paris at the Embassy of the Balkan state of Pontevedro rather than in the Germanic Birkenfeld of the original play or in Léon’s originally posited, but too real, Montenegro. Baron Mirko Zeta (Siegmund Natzler) is desperate to find a Pontevedran husband for the ‘merry widow’, the young and hugely wealthy Hanna Glawari (Mizzi Günther) who is currently being chased by half of male Paris. He and the fatherland cannot afford to let Hanna’s millions go into a foreign exchequer. He selects for this delicate patriotic task the womanizing, boozing but indubitably charming attaché Count Danilo Danilowitsch (Louis Treumann). Unfortunately Danilo and Hanna are rather more than old friends from the days before Hanna’s wealthy marriage and Danilo has sworn that he will never again say `I love you’ to the woman he regards as venal. It soon becomes clear, however, what his feelings really are, for when Hanna steps in to save the Ambassador’s wife, Valencienne (Annie Wünsch), from an embarrassing if innocent exposure in a tete-à-tete with the sexy young Camille de Rosillon (Karl Meister), the furious Danilo sweeps off to Maxim’s to find consolation with the girls of that friendly establishment.Hanna sets up part of her mansion as an imitation of Maxim’s and, there, the amazed Danilo comes to discover that the merry widow loses her money should she remarry. His pride assuaged, he now proposes, only to find — as all ends happily — that the money goes to the new husband.

Lehár’s score gave his four principals plenty of opportunities, both the leading pair who, in good Gaiety Theatre tradition, were light-comedy actor/singers, and their straighter-singing secondary counterparts.

Hanna made her first entrance to a cascading number (`Bitte meine Herr’n’) which immediately established her as lustige, performed the mythological tale of the `Vilja’ as a party-piece, and shared the `Dummer Reitersmann’ duo and the evening’s big waltz tune, `Lippen schweigen’, with Danilo, whilst he, apart from the duets, saluted the high-life in `Da geh’ ich zu Maxim’ and the `Ballsirenen’ waltz. Valencienne and Camille shared three soprano/tenor set piece duets (`Zauber der Hauslichkeit’, `Ich bin eine anständige Frau’ and the Pavilion duo with Camille’s fine-spun solo `Wie eine Rosenknospe’) in more vocal manner.

The lower-comedy area, headed by Zeta and his colleagues Cascada (Carlo Böhm) and Saint-Brioche (Leo von Keller), came to the fore in a swinging march octet (`Ja, das Studium der Weiber ist schwer’), whilst Valencienne led the grisettes of Maxim’s in a lively song-and-dance routine (`Ja, wir sind es die Grisetten’), choreographed by Professor van Hamme, alongside some particularly fine finales.

Almost every portion of the Die lustige Witwe score became familar and popular in the years which followed but it was, perhaps, the big waltz duet and the march octet which stood out from the crowd at first.

The original Viennese starts of “Die lustige Witwe”, Mizzi Günther and Louis Treumann.

The success of Die lustige Witwe was never in doubt. The show ran through the spring at the Theater an der Wien, totalling 119 performances by the time, at the end of April, that the traditional summer closure began. Die lustige Witwe did not, however, close but transferred first to the Raimundtheater and then to the Volksoper to continue its run with some 69 guest performances. The two stars held their places, but amongst the minor characters now appeared both Julius Brammer (Cascada, after having originally been Pritschitsch) and Robert Bodanzky (Pritschitsch), before long to be much better known as librettists. When the Theater an der Wien reopened in September, Die lustige Witwe resumed and on 11 January 1907 it passed its 300th, and on 24 April 1907 its 400th performance. Lehár composed a new overture (`Eine Vision’) for the latter occasion, and conducted an expanded orchestra of a hundred players in celebration.

In the meanwhile, the foreign productions had begun. Max Monti opened Die lustige Witwe at Hamburg’s Neues Operetten-Theater, with Marie Ottmann and Gustave Matzner starred and Poldi Deutsch as the Ambassador for `Pontenegro’, little more than two months after seeing it at the Vienna première and, soon after, the Hamburg company, which had played some 250 performances on its home ground within seven months, introduced the show to Berlin. Their success was, again, indubitable, and the show was promptly taken up for a local production at the Theater des Westens (1 March 1907). It remained there for 262 performances.

Budapest followed with, as usual, the first foreign-language version, an Adolf Mérei adaptation produced at the Magyar Színház with Olga Turchanyi (later Klára Küry, Ilona Szoyer) and Ákos Ráthonyi starred.

It passed its 200th performance at the end of May before the show was taken up by the Király Színház, where Ráthonyi was paired with Sári Fedák, and then at the Budai Színkör.

Die lustige Witwe was translated into Czech, Norwegian, Russian, Swedish, Croatian and Italian (Milan, 27 June 1907) before it received its first English performance, at London’s Daly’s Theatre, in a version credited variously to Edward Morton (best known as the author of San Toy) or to Basil Hood, and lyricist Adrian Ross.

Lily Elsie as the Merry Widow.

The book underwent some alterations for the London presentation of the show initially announced as The Jolly Widow. Some tended to the clichéd — Danilo became a Prince, for example — others removed things which would have seemed odd to English ears. In the British version the final scene takes place in the real Maxim’s rather than a reproduction at the widow’s home (yet years later the libretto for London’s Primrose pinched precisely Léon and Stein’s plotline). Lehár himself was on hand to help with the adaptation and, at Edwardes’s request, he provided two additional songs, one to feature Mabel Russell as a third-act grisette (`Butterflies’) and the second to give Bill Berry, cast in the small rôle of Nisch, a number declaring that although `I was born, by cruel fate, in a little Balkan state …’ he had now become `Quite Parisian’. There were other alterations, too. The `Zauber der Hauslichkeit’ duet was turned into a solo for Robert Evett as Camille, and the rôle of Valencienne (here called Natalie) was reduced further by giving the Grisetten-Lied of the last act to Gertrude Lister as another grisette.

Edwardes followed the light-comedy lead casting of the Viennese production by choosing American Joe Coyne, who had played light-comedy rôles for Edwardes in America before making his British début earlier in the year as the comic hero of Nelly Neil, to be his Danilo.

Lily Elsie, who had been moving up through smaller rôles in Edwardes productions, was cast as a younger, prettier, and slimmer widow (now called Sonia) than previously, and accredited comic George Graves was given leave to play up the rôle of Zeta (now called Popoff) which he did largely by sticking in a self-written chat about a fowl called Hetty and her propensity for producing bent eggs. The fine singing was left to Evett and another American, soprano Elizabeth Firth (Natalie).

The English Widow proved as popular as her Continental counterpart, running solidly for two years and two months, a total of 778 performances, before beginning the round of tours, and it launched in Britain, as it would elsewhere, a mad rage for Viennese shows which would last until the war.

Its songs and a bit of millinery merchandising called the `Merry Widow Hat’ became the hits of the day.

The Maxim Girls in Henry Savage’s New York production.

Henry Savage’s New York production continued the series of Merry Widow triumphs. Savage used the London adaptation, now uncredited and with `Quite Parisian’ omitted, and cast the bright and friendly looking actor/dancer/singer Donald Brian as Danilo with Ethel Jackson, a former D’Oyly Carte chorine whose Broadway credits over half-a-dozen years were good if scarcely starry, as Sonia. The waltz, the hat, the stars and the strains of Vienna all came together once more in an enormous hit which produced 419 Broadway performances and, as in London, set up the fashion for all that’s Viennese.

Theatrical mythology has every country unwillingly taking on Die lustige Witwe without any expectation of success.

Given its untarnished record of triumph, this seems unlikely. Yet Paris did not welcome La Veuve joyeuse until more than four years after the Vienna production — by which time it had been seen in Cairo, in Shanghai, in Melbourne and in Johannesburg — and it was not one of the major Parisian musical producers but Alphonse Franck at the Théâtre Apollo who finally ventured. Franck gave the text to the most popular upmarket comedy writers of the day, Gaston de Caillavet and Robert de Flers, for adaptation and they, like the British, made their amendments to the original. The widow, now called Missia, became an American brought up in Marsovie (ex-Pontevedro, Pontenegro, Montenegro). Whether this was because Franck cast British soprano Constance Drever (a London take-over) in the rôle, or whether Miss Drever was cast because of the change of nationality (American, after all, at this period, always meant rich), is not known, but to this day the French script of La Veuve joyeuse bears the instruction that Missia is to be played with an English (sic) accent, touched with a little Slav. The French Danilo is a Prince gone broke through gambling. In line with London, the Ambassador remained Popoff and the last act went to Maxim’s, although the extra numbers disappeared along with Graves’s excrescences and Hetty the Hen. The truly dashing light baritone Henry Defreyn was cast opposite Miss Drever, Charles Casella (Camille de Coutançon) and Thérèse Cernay (Nadia) had the duets, and Félix Galipaux was Popoff.. Franck’s production was an enormous success, played 186 times consecutively for its first run, and was regularly reprised at the Apollo in the years that followed with Defreyn repeating his rôle endlessly opposite Alice O’Brien and other Anglophone (and later not so very Anglophone) ladies.

Australia followed the personality-plus-singing style in casting its Merry Widow when local soubrette Carrie Moore, who had had considerable success on the London stage, introduced the rôle of the widow to audiences in Melbourne and later the rest of the country.

The piece had a fine success, and it was regularly played in Australia thereafter, with the change in values from personality performance to singing ability being particularly noticeable as local divas such as Gladys Moncrieff and, later, Joan Sutherland succeeded to the rôle of Hanna/Sonia.

The success of Die lustige Witwe prompted many burlesques throughout the world. In Germany, Julius Freund authored a pasticcio, Der lustiger Witwer, with music by Max R Steiner and others attached, which later played Danzers Orpheum in Vienna (ad Lindau, Antony 9 February 1907), the Folies-Caprice presented a one-act Die lästige Witwe (20 August 1908) and a `sequel’ depicting Die lustige Witwe in zweite Ehe (the merry widow’s second marriage), written by Max Hanisch and composed by Karl von Wegern, was played both in Vienna (Apollotheater 1907), where Annie Danninger and Eugen Borg burlesqued Günther and Treumann’s creations, and in America (Deutsches Theater, Philadelphia 10 May 1909, and as The Merry Widow Remarried at Cincinatti July 1909). In Vienna, Lehár himself had fun with a little bit of his show, turning out a one-acter for the Theater an der Wien’s studio theatre, Hölle, called Mitislaw der moderne, which allowed Louis Treumann to parody his own performance as Danilo.

The immensley successful silent movie version from 1925, directed by Erich von Stroheim.

Hungary saw A vígadó özvegy (Albert Heidelberg/Károly Ujvary, Emil Tabori, Budai Színkör 25 July 1907), France a dozen or so parodic pieces including La Veuve soyeuse (Eugène Joullot, Henry de Farcy, 5 March 1909) at the Parisiana, Moins veuve que joyeuse, Ni veuve, ni joyeuse and La petite veuve joyeuse (Café Belleville 22 March 1913) whilst in New York Joe Weber produced a highly successful Merry Widow Burlesque which allowed Lulu Glaser and Blanche Ring as ‘Fonia’ an unlikely crack at the widow’s rôle. The American musical His Honor the Mayor threatened in song `I Wish I Could Find the Man Who Wrote the Merry Widow Waltz’ and went on to say what the singer would do to him. In London, George Edwardes sued Henri Pélissier’s Follies not for burlesqueing the Merry Widow but for playing its music whilst he was still running the show. That problem, of course, raised its head elsewhere and a curious lawsuit arose in New York when Savage attacked one variety house for playing The Merry Widow without permission. The producers claimed that their production was not The Merry Widow, it was an adaptation of L’Attaché d’ambassade with music taken from Planquette’s Le Paradis de Mahomet and other sources which just happened to sound like Lehár’s score.

Inevitably, Die lustige Witwe made its way on to film. The first films including a Hollywood one with Mae Murray and John Gilbert, were silent, later versions proved not terribly faithful, whether emanating from America (MGM’s 1934 version with Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald and a 1952 repeat with Lana Turner and Fernando Lamas) or from Austria (1962 with Karin Hübner and Peter Alexander). A projected 1980s British film which, like this last, used the Operette as part of another story, vanished off the schedules without being made. Two pieces put out by Vitagraph in 1910 as Courting the Merry Widow and The Merry Widow Takes Another Husband were fakers that used the famous title to try to interest customers in what was no more that a one-lady, two-men short.

Major revivals have appeared regularly in all the main musical-theatre centres in the 90-plus years since the widow’s first stage appearances as Die lustige Witwe established itself as the outstanding representatative of Vienna’s Silver Age on the international stage.

London saw Carl Brisson three times as Danilo, paired with Evelyn Laye, Nancie Lovat and Helen Gilliland, but if the last of these signalled a switch to a more legit singing widow, a reprise starring Madge Elliott and Cyril Ritchard put the ball squarely back in the light-comedy area. The last commercial London production of the piece was in 1969 with Lisbeth Webb. In New York, where revivals had passed in 1921, 1929 and 1931, musical film-stars Marta Eggerth and Jan Kiepura played the piece in 1943 before going on to repeat their performances around the world. In both countries the piece then passed into the opera houses, with June Bronhill initiating the Sadler’s Wells Opera production with Christopher Hassall’s new translation, and the New York City Opera and Beverley Sills putting the new very vocal slant on the piece in America. Since then the rôle of the widow has become meat for such operatic divas as Roberta Peters, Joan Sutherland, Lisa della Casa and Anna Moffo — a long way from the pretty-voiced personality performances of such as Mizzi Günther and Lily Elsie.

The Ernst Lubitsch film version of the “Merry Widow”.

In Vienna the piece remains regularly in the repertoire of the Volksoper, which admits it finds it difficult to cast a Hanna with the personality the rôle has traditionally maintained in Austria but also with the now more solid vocal equipment modern tastes require, but the show stood up for a commercial run as recently as 1967 when the Theater an der Wien hosted a season of 309 performances with the ageing but ineffably dapper Johannes Heesters, repeating the Danilo on which Lehár had earlier posed `best ever’ laurels, playing opposite Ilona Szamos. In Germany, on the other hand, the piece, which has elsewhere suffered surprisingly little from the depredations of directors out to make themselves noticed by setting it in Greenland or the 14th century, has had some rather extreme treatments. An extravagantly reorganized and reorchestrated version (ad Rudolph Schanzer, Ernst Welisch), with Fritzi Massary and Max Hansen, was staged by Erik Charell at the Grosses Schauspielhaus in 1929, and in 1979 the Deutsches Oper hosted a version in which Wagnerian soprano Gwyneth Jones (who is not, in fact, the only Brünnhilde to have also played the widow in Germany) appeared as Hanna.

In Paris, with no operatic venue into which to retreat, La Veuve joyeuse has remained resolutely opérettique through regular revivals, the most recent of which was at the Châtelet in 1982. After Mary Lewis (1925) and Corinne Harris (1934) the French productions stopped importing their Missias and Jeanne Aubert starred with Opéra-Comique baritone Jacques Jansen in 1942, followed by singing actress Marina Hotine (1951), Jenny Marlaine (1957) and the Opéra-Comique’s Géori Boué (1962) before a multi-cast effort in 1982.

Budapest, too, has welcomed regular revivals of Merei’s adaptation, most recently at the F*o*városi Operettszináz in 1995 (24 March).

The score of Die lustige Witwe has been used as the basis for two ballets, one by Maurice Béjart (1963) and the second, with the score arranged by John Lanchbery, produced by the Australian Ballet. This latter arrangement, which included choral pit vocals, was played in New York and at the London Palladium with Marilyn Jones/Margot Fonteyn dancing the rôle of the widow.

Germany: Neues Operetten-Theater, Hamburg 3 March 1906, Berliner Theater, Berlin 1 May 1906; Hungary: Magyar Színház Víg özvegy 27 November 1906; UK: Daly’s Theatre The Merry Widow 8 June 1907; USA: New Amsterdam Theater The Merry Widow 21 October 1907; Australia: Her Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne 16 May 1908; France: Théâtre Apollo La Veuve joyeuse 28 April 1909;

Films: MGM 1925 (silent), MGM (Eng) 1934, MGM (Eng) 1952, Sacha Films/Herbert Gruber 1962 (Ger)