Alan Lareau

Operetta Research Center

12 March, 2022

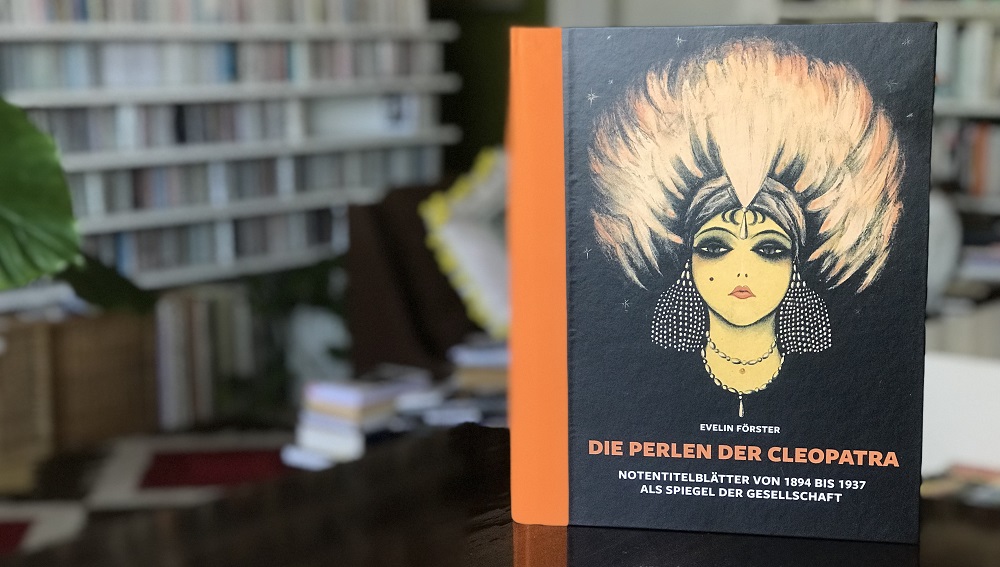

Vamps, policemen, harem dancers, waiters, dandies, grotesque dancing couples, and film stars populate the covers of early twentieth century sheet music editions, what Evelin Förster for lack of a standard German term calls Notentitelblätter. The images represent a forgotten medium of popular music for home use at the parlor piano and performance in social gatherings. Some five hundred illustrations fill the oversized, 370-page book Die Perlen der Cleopatra: Notentitelblätter von 1894 bis 1937 als Spiegel der Gesellschaft, self-published by the Berlin performer and historian. Rediscovering this artistic medium, forgotten documents of our musical entertainment tradition, and the diverse fates behind this chapter of early twentieth century cultural history evokes fascination on many levels.

Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra,” 2022. (Photo: Private)

After moving from East to West Berlin just before the wall fell, Evelin Förster began her career as a chanson singer highlighting little-known music of the Weimar era (she released two CDs of songs, “Ach die Kerle,” 1994, and “Das Lied der Gesellschaft,” 2016), then found her niche with historical lecture-performance events presenting the culture of fashion through writings found in the popular press, complemented by contemporary topical songs.

Evelin Förster guiding visitors through the exhibition “Berlin in the Revolution of 1918/19.” (Photo: Private)

She turned her attention to the history of women lyricists and composers with the performance project Die Frau im Dunkeln, out of which grew a book, a sheet music album, and a 2-CD audiobook. In the course of her background research, she began collecting rare sheet music from early popular entertainment: operetta, musical theater, Couplets and Schlager, cabaret songs, dance numbers—given her performance interest, no opera or art song, though some Salonstücke or salon music, dilettante pieces for home entertainment, found their way into her ever growing archives.

Evelin Förster’s “Die Frau im Dunkeln: Autorinnen und Komponistinnen des Kabaretts und der Unterhaltung von 1901-1935.”

There has been little previous research on sheet music covers, largely catalogue-style compilations such as Udo Andersohn’s Musiktitel aus dem Jugendstil (1988) the exhibit guide In der Bar zum Krokodil: Die Schlagerwelt der Zwanzigerjahre (ed. Hildegard Wiewelhove, Bielefeld, 2013), or Oh Donna Clara: Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco (ed. Walter Labhart, 2017).

Frau Förster’s work goes in new directions, exploring the multi-faceted stories behind the images and their cultural interactions and interventions. In 2018, she displayed a selection of her music covers in an innovative exhibit on Berlin in the Revolution of 1918/19, which juxtaposed historic photography with music and popular entertainment as parallel realities in the year 1919, and she reprinted many of those in the exhibit catalogue.

The cover of the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.” (Verlag Kettler)

As performance opportunities disappeared in the wake of the Covid pandemic, Förster found a new calling in publicizing her now vast archives through a high-quality book publication. Commercial publishers found the topic of historic sheet music covers too obscure to be lucrative, especially given the ever rising cost of printing, so she self-published the volume and fulfilled her own highest artistic and production standards.

Music as a Mirror

The thesis running through the book is “that entertainment music immediately reacted to the newest social themes and events, and processed or replicated them” (274). This goes not just for the songs themselves, but also the covers of the sheet music under which they were marketed.

The volume in the style of an art exhibit catalogue is organized by cultural themes, rather than musical genres or chronology, with fourteen chapters and three Exkurse or digressions, each investigating topics such as images of women, dancing, typography and design, travel, advertising, and international influences in popular music.

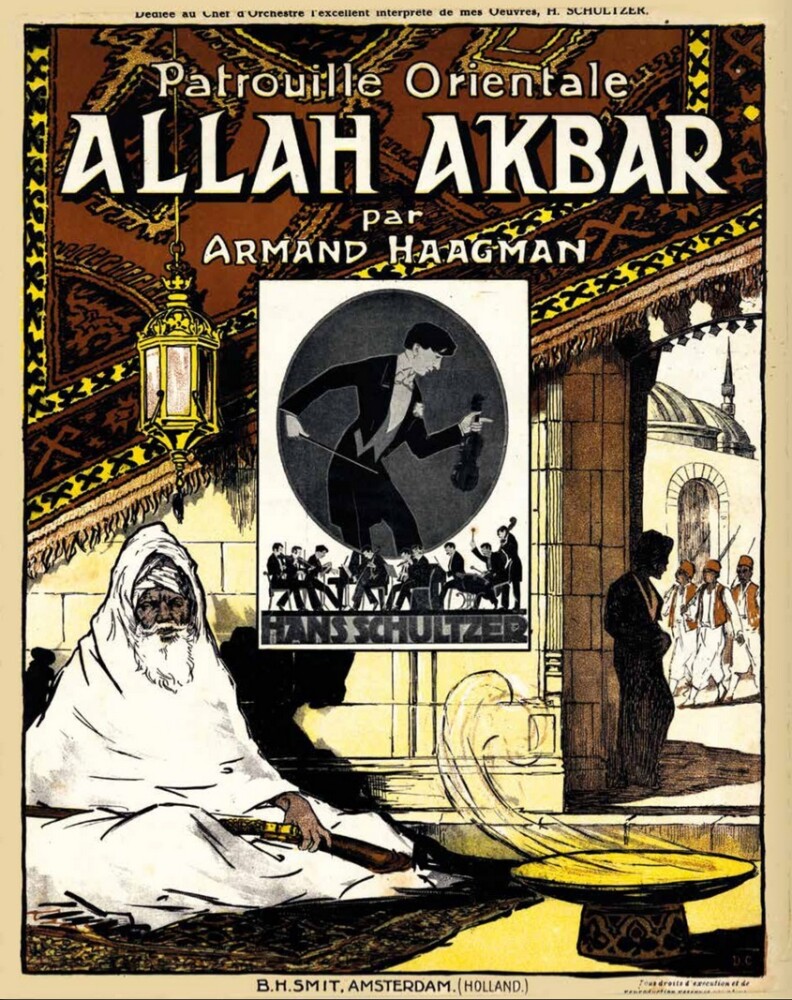

The book has an “Oriental” section entitled “Reisen und Fernweh,” featuring sheet music covers such as “Allah Akbar” by Armand Haagmann. (Photo from Evelin Förster’s “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

The text (in German only) draws largely on etiquette manuals, alongside fashion and advice columns in the popular press, to anchor the illustrations in their social context. As Förster reads the images for their reflection of changing style, morals, and identities, she touches on aspects such as bobbed hair, monocles and top hats, rules for kissing a lady’s hand, social dance crazes, tourism and exoticism, nudism, metropolitan lifestyles, and expanding sexual freedoms.

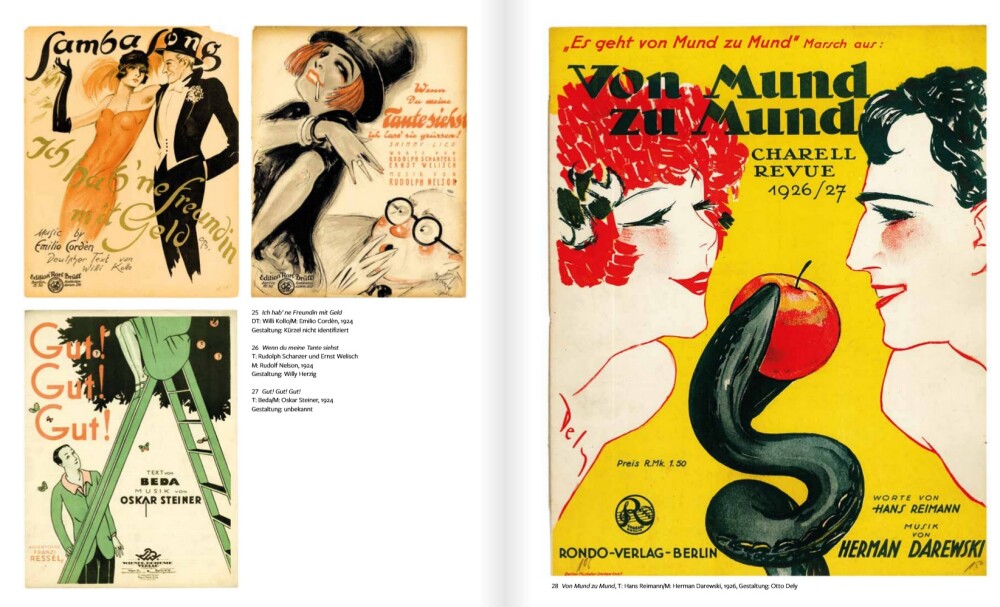

Double page from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra,” 2022.

Her interest lies above all in the 1920s, their fashion and manners, and representations of new femininity on the verge of modernity.

Stories of the Creators

Throughout, Evelin Förster pays tribute to the many Jewish artists who worked in the popular entertainment industry as writers, composers, and performers. This is explicitly addressed in the biographical sketches at the end of the volume, which note which figures were emigrés or victims of Nazi persecution.

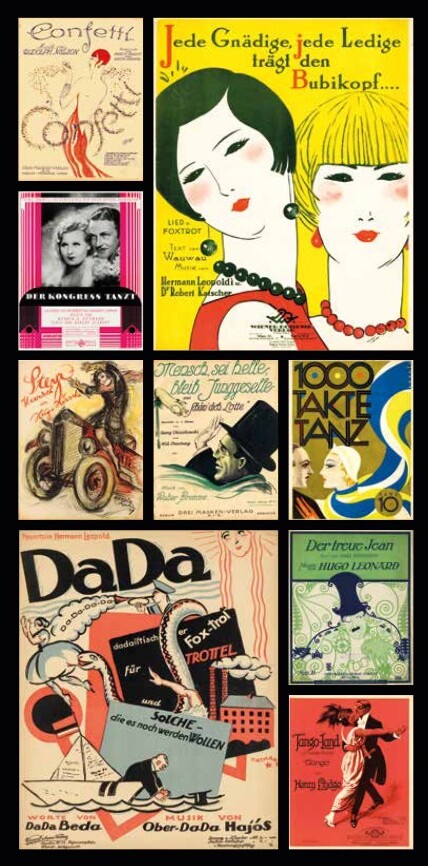

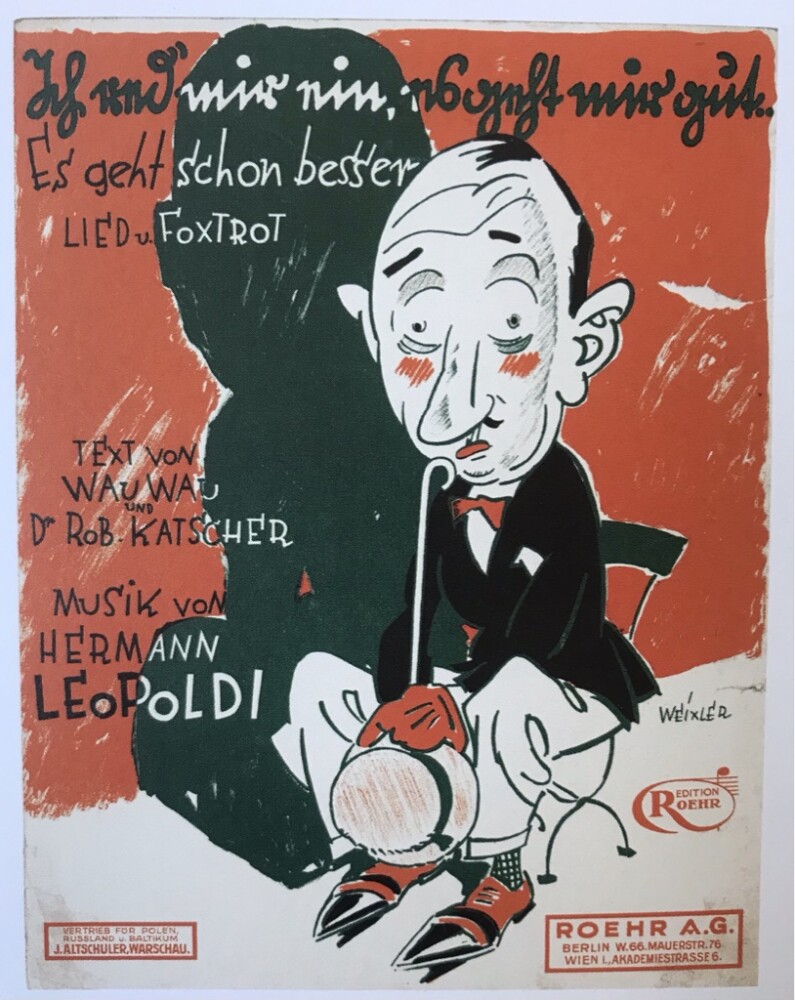

Jewish creators who escaped the Nazi regime include Hugo Hirsch, Werner Richard Heymann, Jean Gilbert, and Hermann Leopoldi (the latter after incarceration in two concentration camps). One of the most prolific lyricists, known for his operetta songs (above all for Franz Lehár) but also his Schlager and new German lyrics for American pop songs, is “Beda,” Dr. Fritz Löhner-Beda, who died following a beating suffered as a forced laborer in Auschwitz.

Various sheet music covers from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra,” including songs written by Fritz Löhner-Beda.

Others remained in Germany and its subjugated territories through the “Third Reich,” including Lehár (despite his wife’s Jewish origins), Willi and Walter Kollo, Willy Engel-Berger, and even the Jewish operetta composer Edmund Eysler, who had been named an honorary citizen of Vienna, though his works were banned. (For a multimedia portrait of Eysler’s life and work, see the portrait by Michael Haas at Forbidden Music.)

Surprisingly, few of the graphic designers, many of whose work remains anonymous, appear to have been Jewish, and many continued their careers in Germany through World War Two. The few female creators, such as lyricist Eddy Beuth or illustrator Elisabeth Linge, are the exception that prove the rule.

The deeply researched volume closes with a voluminous bibliography. More study remains to be undertaken on the German music industry of the early twentieth century, above all its marketing and distribution of popular music through sheet music editions and its negotiation of social, economic and political changes.

Sheet music cover for the song “Ich red’ mir ein, es geht mir gut” by Hermann Leopoldi, with words by Wauwau and Robert Katscher, 1926. (Photo from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

Icons of Modernity

But Evelin Förster’s book lives above all through its images. Popular song excelled in topicality, and accordingly, the pictures on the covers speak to the sensibilities of the day, not just to illustrate the lyrics but above all in order to attract interest and promote sales. The pictures revel in women’s hair, flowing or revealing dresses, winking or leering seduction, and oodles of flowers—images that ooze with sensuality or evoke laughter, sometimes involuntarily. Many illustrations recall works lost to our historical memory, such as the operettas Die Bacchusnacht (1923) by Bruno Granichstaedten or Jadwiga (1901) by Rudolf Dellinger.

The sheet music cover for “Bachusnacht,” an operetta by Bruno Granichstaedten and Ernst Marischka, 1923. (Photo from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

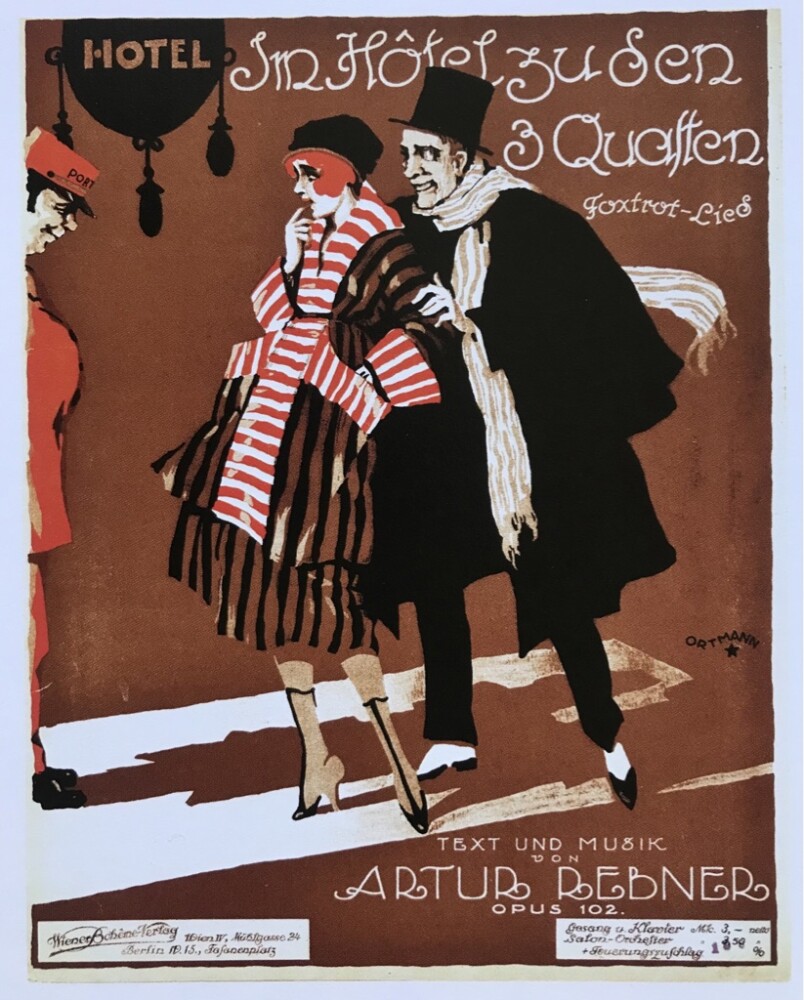

The most ambitious and elaborate covers are from the years before World War One: bold and sinuous Art Nouveau or Jugendstil sensuousness alongside grotesque humor for music hall numbers. Though spiced with contemporary references, the illustrations of the 1920s sport less detail and more caricature, often with an impudent and ironic tone, sometimes featuring a sophisticated Art Deco flair.

Sheet music covers showing various types of “modern” men, from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra.”

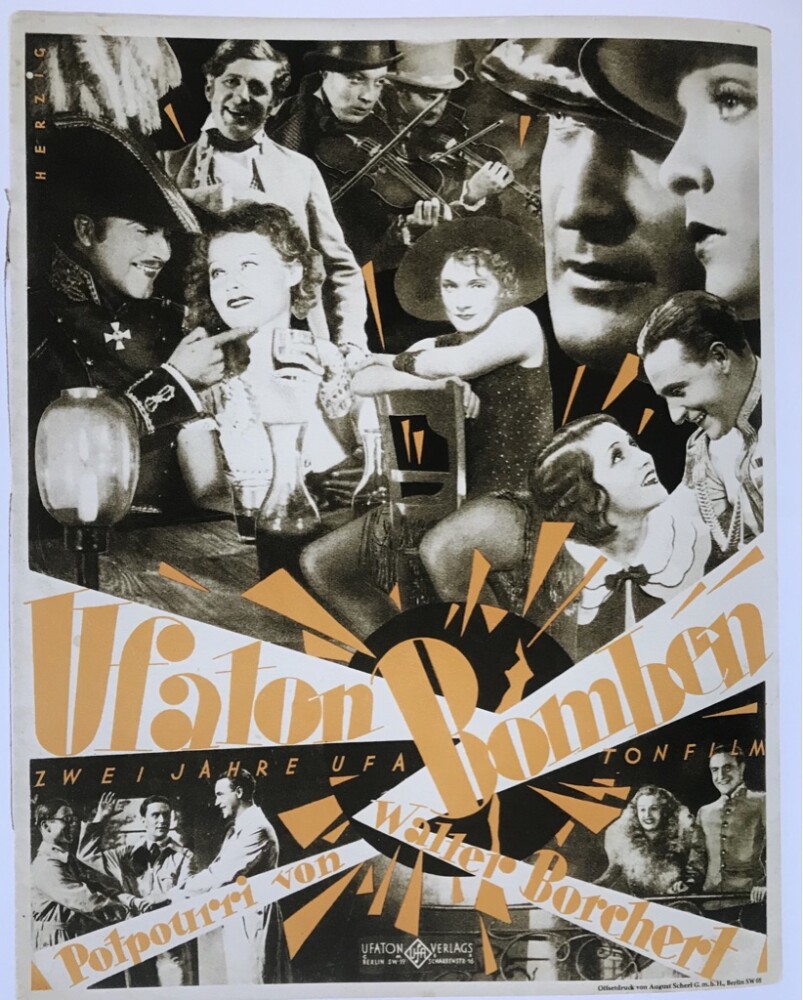

With the 1930s and the increasing popularity of photography and sound films (as well as the growing influence of the mass media of radio, popular magazines, and gramophone records), the sheet music becomes more generic and artistically uninteresting, largely star-oriented, although some covers adopt innovative photomontage techniques. Of the many designers represented here, three stand out as representative of their eras: Paul Telemann, Wolfgang Ortmann, and Willy Herzig. (For large online collections of low-resolution sheet music covers from around the world, see https://www.imagesmusicales.be and https://www.notenmuseum.de ).

Evelin Förster markets many images from her archives on the database akg-images, and hopefully she will display some of the works in her collection in future exhibitions.

A provocative photomontage illustrates the medley “Ufaton Bomben” (1932). (Photo from Evelin Förster’s “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

Collectible Treasures

The selection of sheet music included here is subject to the holdings of Evelin Förster’s collection, so some readers may discover their favorite songs and shows missing, especially given how rare these editions can be. One famously exclusive cover, which Frau Förster is proud to possess, is the parodistic song “Dada: dadaistischer Fox-trot für Trottel und solche—die es noch werden wollen” of 1920, a sendup of the rebellious artistic movement featuring an appropriately grotesque design by Wolfgang Ortmann. (An original copy recently sold at auction for 2,400 Euros.)

Many other images she reprints are completely unknown, such as the hilarious Ensemble-Scenes and eccentric solos published around 1900: a now-forgotten genre of humorous material written for amateur performance in the household and at social gatherings, or possibly for minor music halls.

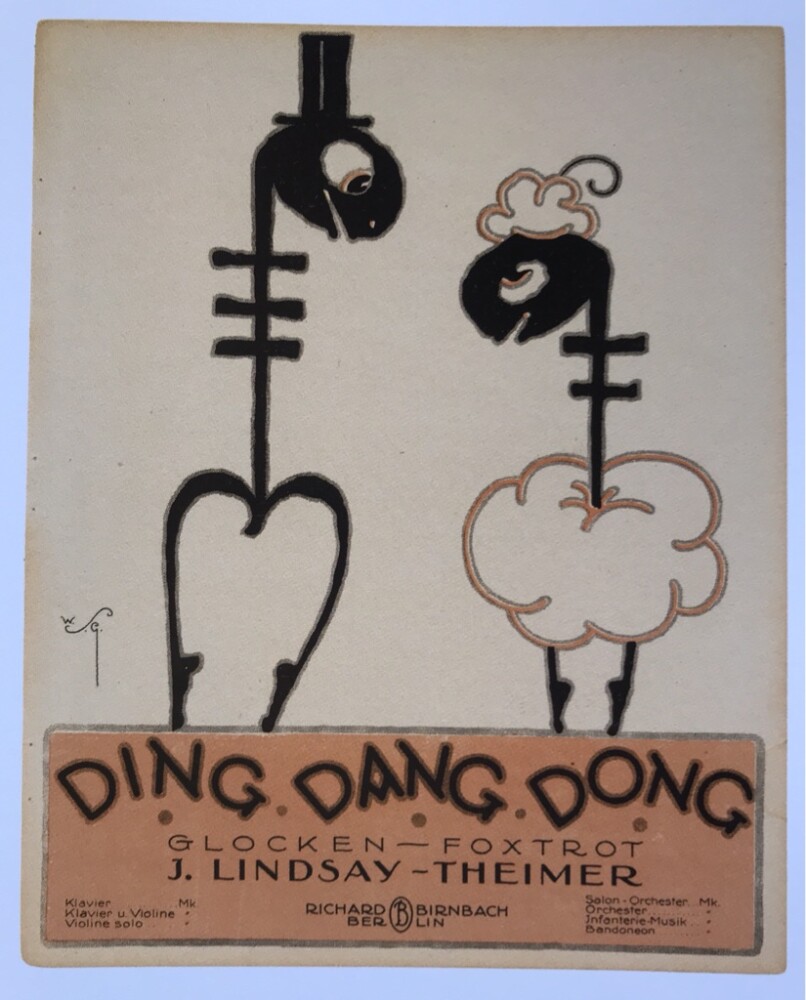

Sheet music cover for the foxtrot “Ding Dang Dong” by J. Lindsay-Theimer, 1921. (Photo from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

Another musical vein little remembered today, though especially popular with bands and in home performance in its day, is that of salon music and potpourris or medleys. On the other hand, two important cultural trends of the twenties are not showcased in this assortment: African-Americans and jazz musicians, and gender-crossing and drag, as they are not found in Frau Förster’s archives.

The book features fine color printing, hardcover binding, and thick paper—but the biggest challenge is that the large tome (24×30 cm) is so heavy that one can’t hold it to read, for after a few minutes hands and arms begin to ache, so that one needs to lay it on a table to peruse its rich offerings.

Two pages page from Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra,” 2022.

Readers will also be curious to know more about the songs behind the cover illustrations. Förster discusses some of the songs in detail and offers a few excerpts of the lyrics, and historical recordings of many, indeed a surprising number, of the titles reprinted here can be found on YouTube.

Die Perlen der Cleopatra opens with the programmatic motto “Gegen das Verschwinden der Vergangenheit”: Against forgetting the past. Evelin Förster’s ambitious book deserves recognition for three accomplishments: rediscovering a lost art form, remembering bygone musical and entertainment genres, and memorializing persecuted Jewish artists.

The book can be purchased directly from Evelin Förster via her homepage for 49.90 Euros plus postage. (International readers should be aware that transatlantic postage rates are considerable.)

Sheet music cover for “Im Hotel zu den 3 Quasten” (“In the Hotel of the Three Tassels”) by Arthur Rebner, 1920. (Photo from Evelin Förster’s “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”)

For a playlist of historical recordings and piano rolls to accompany the images in Evelin Förster’s book, readers can download this PDF with live links to online audio. (Click here for the playlist “Perlen der Cleopatra”.)