Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

30 April, 2020

It doesn’t happen often that an operetta composer gets that much attention in the general media, certainly the Germany language press. But Lehár is in a league of his own it seems. Instead of adding yet another biographical article to the already endless jubilee list, we want to discuss a few fundamental questions surrounding Lehár and the way his operettas are performed today.

Franz Lehár (2nd from left) with his wife Sophie and George Gershwin when he visited Vienna in 1928. (Photo: Atelier Willinger / Theatermuseum Wien)

Because there are many misunderstandings regarding this composer born on 30 April, 1870, in the Hungarian Komárom, now a city in Slovakia. Which prompted his rival Emmerich Kálmán to write to the director of Theater an der Wien in 1927: “Just keep that Slovak out.” It was the year that Lehár’s Zarewitsch premiered in Berlin, with Richard Tauber in the title role, and it was while Kálmán was working on his own Charleston infused Herzogin von Chicago for Vienna with Hubert Marischka as an alternative operetta hero. In public, Lehár and Kálmán shook hands and smiled. But they represented totally opposite operetta ideals, at the time.

Richard Tauber and composers Lehár and Kálmán.

The Beginning of a New Era

Many operetta historians claim that Franz Lehár was the “initiator” and/or “inventor” of the so called Silver Era Operetta. In Richard Traubner’s Operetta: A Theatrical History we read: “Franz Lehár ushered in the silver Viennese operetta with his greatest work, Die Lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow), in 1905. Though not immediately recognized as such, it was the beginning of a new wave of modern operettas in which the waltz was used for romantic, psychological plot puroses, and danced as much as sung. Some of the old conventions of nineteenth-century operetta remained, but vaudeville and revue elements were often kept in check as much as possible.”

A scene from Weber’s Burlesque “The Merry Widow and the Devil,” 1909. (Photo: Museum of the City of New York)

The Merry Widow certainly was the start of a new wave of operettas “Made in Vienna” which influenced almost everything that followed in terms of plot structure, with two constantly battling lovers at the core who cannot express their feelings (“Lippen schweigen”) until the final scene when they find out that they were smitten with each other all along. You can work that into many variations, which is exactly what Viennese operetta librettists did.

Modern-Day Viennese Style

Interestingly, Karl Westermeyer describes the Merry Widow as the initiator of the “neuzeitliche Wiener Stil,” i.e. the modern-day Viennese style. He does not use the word “silver” in his 1931 publication anywhere. Instead, he describes the 19th century works by Johann Strauss and colleagues as “Die romantische Operette” and “Die Operette unter der Vorherrschaft des Wiener Walzers.” Which is a very precise label pointing to the essence of these works. Westermeyer also emphasizes that the Merry Widow paved the way for the US-American craze for Viennese waltz operettas on a scale unheard of before. A craze that lasted for a few years and brought with it many Broadway productions of works by Oscar Straus, Leo Fall and Emmerich Kálmán, all following the Lehár lead. The West End in London fell for Lehár, too. The Merry Widow was a global phenonenon, and a massive Anglo-American hit. It also made Lehár one of the richest composers of his time. (Much to the chagrin of Richard Strauss.)

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in ‘The Merry Widow’, 1907. Elsie and Coyne are playing the parts of ‘Sonia’ and ‘Prince Danilo’ respectively.

Until the craze subsided, and the Americans created their own operettas and/or moved on to musical comedies. With the Merry Widow remaining a popular title that was adapted by Hollywood to changing public tastes, over and over again, from Stroheim’s 1925 version emphasizing the “perversity” and “kink” of the story, with May Murray and John Gilbert in the lead roles, to Lubitsch turning the whole thing into a screwball comedy starring Jeannette McDonald and Maurice Chevalier in 1934, and onwards to the slick harmlessness of the 1950s with Lana Turner as the dazzling widow.

“Jewish” and “Bolshevist”

Not even the Nazis used the gold and silver terminology; instead they labeled 19th century waltz operettas from Vienna classic “Aryan” operettas, mostly because the composers were all non-Jewish, and they saw Lehár and his famous waltzes as a continuation of that tradition.

Just for the record, the waltz and particularly the Viennese waltz à la Strauss was declared the “most national of all German national dances” in 1940. And this “noble” and “healthy” dance from “Germanic soil” was seen as the ideal cure from the “degenerations” of the “Jewish” and “Bolshevist” influences of the “Verfallszeit” – the time of “decay” pre-1933.

So it was “Aryan” operetta vs. “degenerate” operetta, not gold vs. silver. Though, in effect, the same body of work was meant, since almost every composer that followed Lehár and his Lustige Witwe was of Jewish origin. From a Nazi perspective that put almost all 20th century operettas, apart from Lehár’s, on the unwanted list. And not surprisingly, the respective works disappeared quickly after 1933.

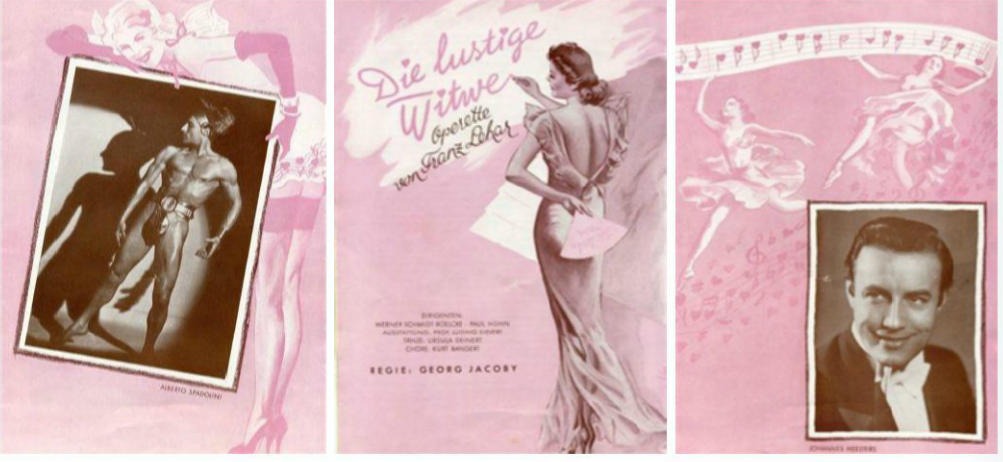

The program for the 1940 production of “Die lustige Witwe” with Johannes Heesters (r.) and Alberto Spadolini (l.). (Photo: Atelier Alberto Spadolini)

When the Nazi terror was over in 1945, the ideological indoctrination of 12 long years remained in many heads. And the idea that 19th century waltz operettas by Strauss were somehow superior to the later works in the wake of Merry Widow remained as well. Obviously, you couldn’t use the old Nazi wording anymore, so some clever Austrians come up with a new terminology in 1947 that basically said the same thing but avoided the problematic words: so operetta history was now divided into gold and silver.

Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Otto, “Die Wiener Operette. Ihre Theater- und Wirkungsgeschichte,” 1947.

Lehár’s famous Gold und Silber concert waltz might have given the cue here. According to the new terminology, Lehár and Merry Widow were the start of the Silver Era but also its highpoint. It was downhill from there on… You can work the rest out yourself.

To this day, many theater directors and classical music conductors believe that Lehár stands high above everyone else, and if an operetta must be played at all in a state subsidized opera house then it should be Strauss’ Die Fledermaus or Lehár’s Lustige Witwe, ideally in an “ennobling” way with symphonic orchestra and “legitimate” voices.

Filled with “Carnal Lust”

Supposedly, such opera voices were what Lehár wanted; at least that’s how legend has it, based on the argument that the composer wrote his late works for Richard Tauber and premiered his last operetta Giuditta at the Vienna State Opera in 1934. Which is taken as evidence that in retrospect all other Lehár operettas – written without Tauber – must also be performed by opera voices, and not just the leading tenor roles (which Tauber might have sung), but every role. The concept has since been applied to all of Lehár’s formerly non-operatic scores, including Die lustige Witwe.

When that show premiered, critic Felix Salten described its modernity thus: “Lehár’s music is hot with an open, boiling sensuality; it is filled with carnal lust.” That’s what sets Lehár apart from earlier composers such as Offenbach who cultivated a different style that is not “our melody,” says Salten: the melody of a new age in which Freud’s exploration of the libido and unconscious dominate.

The world’s first Danilo, Louis Treumann, in a signed 1909 portrait. (Photo: Anonymous / Theatermuseum Wien)

For Salten, the original Danilo on the Vienna stage represented this new age to perfection: Louis Treumann is “an artist of a new kind […]. A young person with eccentric manners and a tendency for the grotesque. […] He is delicate, slim and flexible, a bit feminine. […] There’s a hint of vice and hysteria. […] He is a Menschendarsteller, but thank God not in a naturalistic way. Everything is stylized with him. […] In his meager body passions rage, not in a pathological sense, but a passion that climaxes in ecstasy expressed through dance.”

You might ask yourself when you last applied such a description to any Danilo you saw or heard? It doesn’t apply to Hitler’s favorite Danilo, Johannes Heesters, it hardly applies to Bo Skovhus on the famous John Eliot Gardiner recording that claims to be “historically informed” and following Lehár’s original intentions, and it sadly doesn’t apply to the recent production at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where Nathan Gunn was Danilo next to Renée Fleming as a nostalgic and totally un-modern widow.

Wouldn’t a Danilo like Treuman be far more “modern” by our current standards than any well-meaning and “ennobling” opera star? Why are companies presenting this famous work in such a “wrong” way when they are losing young audiences left and right – and when, in New York, a multitude of Treumann-like actors are available on Broadway?

The Lehár Series on CPO

Record companies such as cpo have made it their mission to release as many unknown Lehár shows on disc as possible in recent years. They do so with the opera people they can affored, avoiding a search for today’s Treumanns (which are definitely out there, also in Germany and Austria). As a result, many of the cpo releases sound mind bogglingly boring, because most opera singers are not trained to be Menschendarsteller who canclimax on stage or in front of a microphone with a hint of vice and hysteria in their voice.

The CD cover for Lehár’s “Die Juxheirat,” 2016 live recording on cpo.

Many of the Lehár shows that have very up-to-date plots – about feminism, sexual liberty, hedonism, racism etc. – make absolutely no impact on any recent CDs. And the world seems forever stuck with tenors belting out “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz” without an ounce of Tauber’s magnetism and daring to go over-the-top.

On Lehár’s birthday it’s worth reminding ourselves of all of this. Because it would be well worth rediscovering the “modern” side of the composer and giving his works a new chance, filled with carnal lust instead of bland “noble” singing. And that applies to the various Tauber operettas, too, from Paganini to Friederike, Land des Lächelns, Schön ist die Welt, and Giuditta.

Stefan Frey’s new “Franz Lehár: Der letzte Operettenkönig.” (Photo: Böhlau Verlag)

For more information on all of the above read Stefan Frey’s great new Lehár biography, which sadly is only available in German. (There are no substantial new English language publications.) Alternatively, listen to the restored recordings of Louis Treumann and Mizzie Günther on Truesound Transfers. Or: simply watch Erich von Stroheim’s 1925 movie of Merry Widow. As Mr. Frey says in his book, it’s probably the best operetta film ever made, and it gives you a very good idea what the magic of operetta is all about. (Even if the YouTube version only uses an organ, instead of the full orchestra which Lehár himself conducted at the Paris premiere.)

Happy birthday, Mr. Lehár!