Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

24 October, 2019

From 10 to 12 January 2019 the University of Leeds is hosting an international operetta conference entitled Gaiety, Glitz and Glamour — or Dispirited Historical Dregs? A Re-Evaluation of Operetta. It’s in affiliation with the project German Operetta in London, New York and Warsaw, 1906–1939 (GOLNY), funded by the European Research Council. We spoke with Prof. Derek B. Scott from the University of Leeds about who is coming to the conference and what the new topics are going to be – and what changes there have been in the English language research world of late. Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy (but very enjoyable) ride!

The University of Leeds in North England.

You are continuing your Gaiety, Glitz and Glamour series in January at the University of Leeds. This time the subtitle is A Re-Evaluation of Operetta. What has the evaluation of operetta been in the past, from a British or English language research perspective? And why is it high time for a re-evaluation?

The most common evaluation of operetta in the past has been that it is an old-fashioned genre, which returned briefly to the stages of Broadway and the West End after the success of Lehár’s The Merry Widow in 1907; it then disappeared during the First World War but came back for a few years in the 1920s. Operetta has tended to be regarded as little more than a precursor to the Broadway musical. According to this narrative, American musicals of the mid-1920s, such as No, No, Nanette and Lady Be Good transformed the appetite of theatre audiences. Yet, if we jump to 1931 we find five premieres of operettas from the German stage produced in the West End. One of them, White Horse Inn, proved to be almost as sensational a success as The Merry Widow had been in 1907, and another, Waltzes from Vienna, ran for over a year and was adapted as a film directed by none other than Alfred Hitchcock.

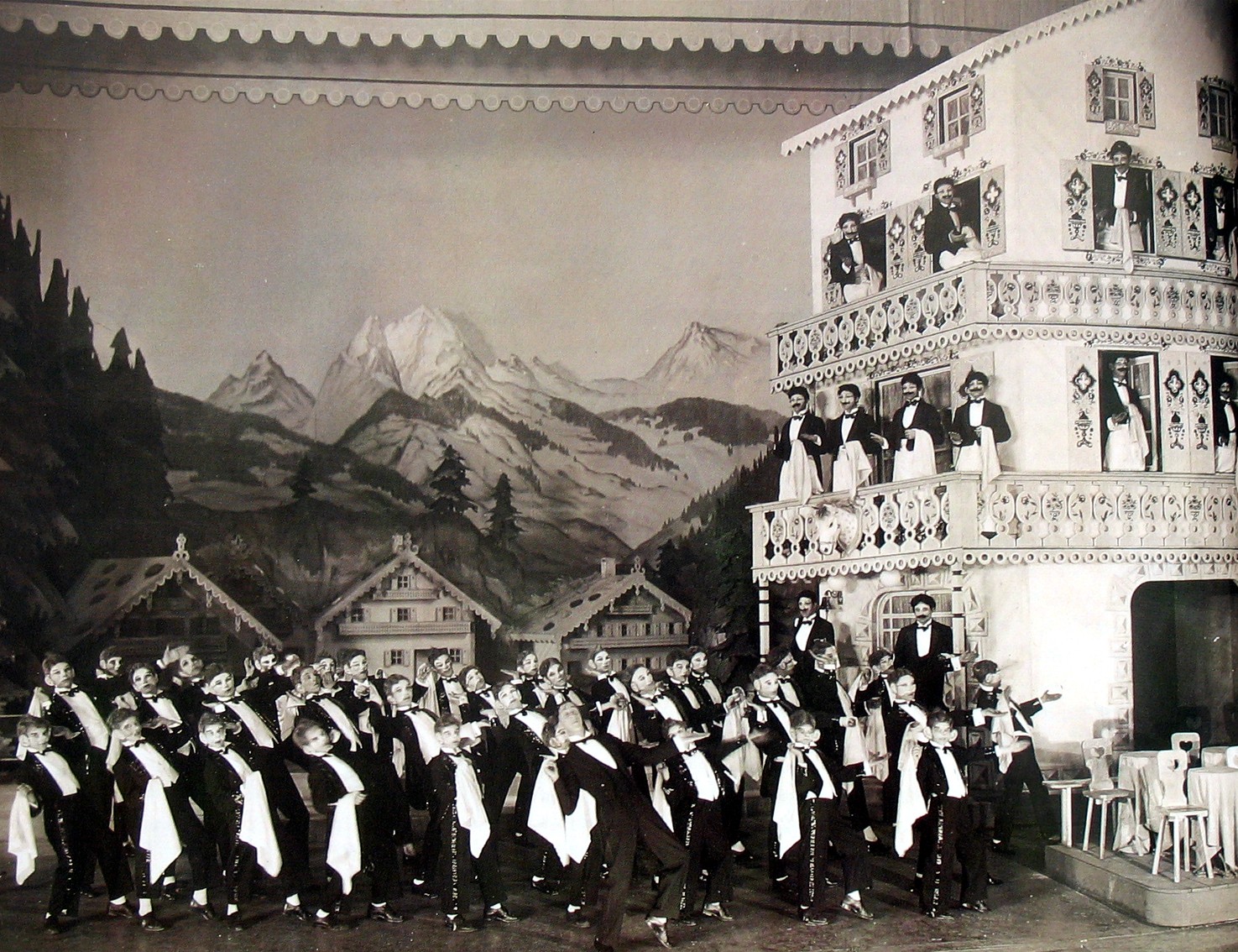

Waiters on parade: the grand marching scene from London, 1931.

What is more, both White horse Inn and Waltzes from Vienna – under the new title, The Great Waltz – were just as successful on Broadway in the 1930s. It is now time to correct the misguided idea that operetta was of minor interest in the UK and USA and investigate the reasons for their being over 60 productions of operetta from the German stage in the West End, and over 70 on Broadway, between 1900–1940. Until recent years, most Anglophone scholarship relating to operetta has been of a cataloguing or plot-descriptive character. What we need now is the critical evaluation of operetta.

Ernst Stern’s fantasy costumes for the girl dancers in the Broadway production of “White Horse Inn.”

For a long time, the standard operetta books in English were by Richard Traubner and Kurt Gänzl. In his 2003 update of Operetta: A Theatrical History, the late Mr. Traubner wrote: “Operetta! Flowing champagne, ceaseless waltzing, risqué couplets, Graustarkian uniforms and glittering ballgowns, romancing and dancing! Gaiety and lightheartness, sentiment and Schmalz.” Is that definition still appropriate? (Has it ever really been appropriate? Where does such a notion come from?)

The idea that there is a serious type of music and trivial type has its origin in the growth of a commercial music industry in the mid-nineteenth century. From then on, critics contrasted “true art” with mere entertainment. It has never been right, however, to understand operetta as nothing more than escapist entertainment. Operetta shines a light on a whole variety of social tensions, desires, aspirations and anxieties. That may be most obvious in nineteenth-century satirical operetta, but it is still to be found in twentieth-century operettas, which frequently engage with modernity, cosmopolitanism, gender relations, transnational business networks, new technology, and so forth.

Cross-dressed hightlight from “New York bei Nacht”: Bernhard Rank as Thusnelda Mohrrübchen (= Miss Carrot). From: John Koegel: “Music in German Immigrant Theater; New York City 1840-1940.”

Certain critics believed operetta was dulling the minds of audiences or making them pre-disposed to be manipulated by those in power, but it can just as easily be argued that audience were perfectly aware of harsh social realities and needed Utopian visions as an emotional release. We should remember that prisoners in Theresienstadt, whose personal circumstances were desperate, made efforts to put on operetta performances.

Richard Traubner’s “Operetta: A Theatrical History.”

For anyone accustomed to the Traubner definition, it might come as a shock that you are dealing with topics such as “Sexuality & Gender,” “Socialist Realism & Totalitarianism,” “Transnational Influence” and “Commerce.” Where will the “Gaiety, Glitz and Glamour” be in that?

The subtitle of the conference, as you have noted, is “a re-evaluation of operetta.” It is hoped that speakers will re-evaluate the notion that operetta can be simply summed up as “gaiety glamour and glitz” as well as challenge the views of critics like Adorno, who saw operetta as consisting of worn-out musical devices being bolted together as if on an industrial conveyor belt. Unlike opera, operetta often had contemporary subject matter, and even when it opted for history or myth there was usually some contemporary resonance (think of the quotation of the tune of the “Marseillaise” when the gods rebel against Jupiter in Orphée aux enfers).

You had a call for papers, and researchers from across the world replied. Were you surprised by the proposals you received? Did anything strike you as new and not much heard of before?

I was surprised that there were so many scholars risking their careers by undertaking operetta research! When I received the proposals for the conference, what did not surprise me was how many different countries were represented. I have always argued that operetta is a transcultural and cosmopolitan genre that crossed national borders with ease. I am really looking forward to the papers that discuss operetta in the context of authoritarian regimes but there are also some papers that seem to break new ground in investigating the business of operetta and the transnational influences on operetta.

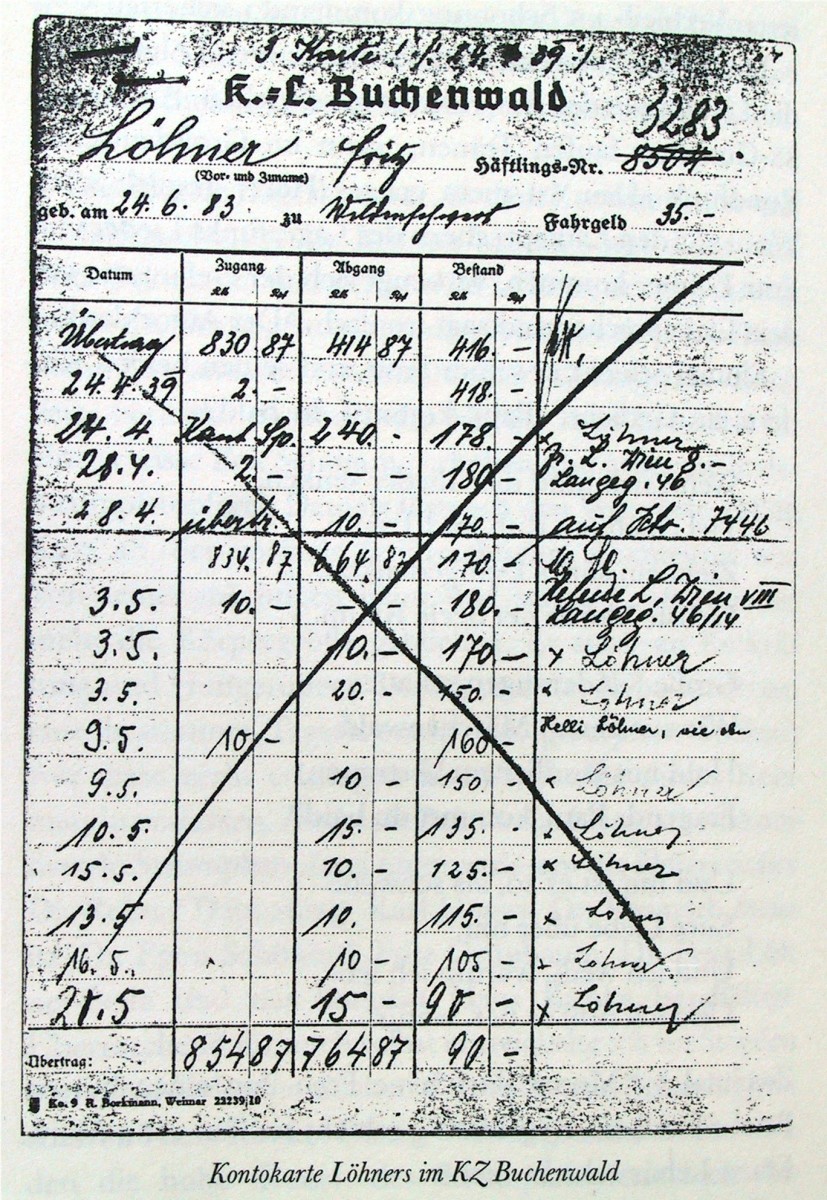

The concentration camp registration card of Fritz Löhner-Beda from Buchenwald. Löhner-Beda wrote the famous “Buchenwald-Lied” while imprisoned there; he died at Auschwitz.

There has been a lot of new operetta research lately. What do you see as the new trends in terms of topics? And: is there a new generation of researchers who bring these topics with them, or why is there such a noticeable shift?

Operetta research has turned away from description to become interpretative and critical. A new trend is that scholars are now eager to investigate operetta productions in the context of cultural history and the social issues with which they engage. One of the most noticeable changes in their published operetta research is a concern to adopt the academic apparatus of footnotes in order to allow sources of information to be validated and verified. I do see evidence of a younger generation of scholars taking an interest in operetta. This evidence is found in recent publications, but also in the response to the call for papers for the upcoming conference in Leeds.

For the longest time it was professional suicide to specialize on operetta as an academic. You yourself had a bizarre experience in Canada in this context. Has that changed – can young researchers build a career with operetta? If so, what has caused the new situation?

You’ve reminded me that Canadian Opera paid for me to fly to Toronto to give a public lecture to accompany the production of Die Fledermaus. It was the first time Canadian Opera had performed an operetta, and it seems that the company had been unable to locate a Canadian musicologist who was prepared to speak about this work! I’m afraid there are still academics who would regard anyone who pays attention to entertainment genres as making a very unwise career choice. Yet, in the 1990s, pop music research suddenly took hold in academia, much to the surprise of traditionalists. Without doubt, it was the challenge to ideas of “high” and “low” art found in poststructuralist and postmodernist theory that prompted this new development. It seems to me the next move is to investigate mainstream culture of the past, and we will never properly understand what this means without studying operetta. It is frequently the cultural middle ground that is neglected in academic work, which often prefers to focus on the predilections of a cultural elite, or on working-class leisure activities.

Do the new topics your speakers will analyze go hand in hand with new operetta titles that have been re-discovered? (And why did it take so god dam long to break free from the eternal Fledermaus and Merry Widow?)

You may be prematurely optimistic in thinking companies have finally shaken off their obsession with Fledermaus and the Witwe. In Leeds, Opera North (the largest English company outside London) has just put on The Merry Widow for the second time in about five years. They have never performed any other operetta from the twentieth-century German stage. But, there again, has the Met? I’ve spoken to Opera North staff, and they are convinced that operetta will not sell seats. They believe the Widow attracts an audience because it is familiar or known by reputation. In other words, they are in the business of confirming taste and not challenging their audience with anything except the occasional premiere of a new opera. Hence, that audience gets older and greyer each year listening to the same things over and over again.

Whenever I mention the upcoming Leeds conference, there are always people who assume it will be largely concerned with Die Fledermaus and Gilbert & Sullivan, with perhaps some Offenbach thrown in. Not so. There are many more papers on twentieth-century operetta.

The major operetta performance impulses have come from Berlin – Barrie Kosky at Komische Oper and then the Gorki Theater with their Spoliansky rediscovery. How has this affected theaters and performers in the English speaking world? (Are conferences like yours paving the way for the stage to follow?)

I am astounded that Barrie Kosky’s innovative productions of operetta have yet to have an impact on Anglophone productions. He has shown that operetta can attract a young audience. I was amazed at the number of young people I saw thoroughly enjoying Abraham’s Ball im Savoy at the Komische Oper in Berlin. I do know that some of those working hard to support operetta performance, such as Ohio Light Opera, feel uneasy about following in the footsteps of the iconoclastic Kosky.

Ohio is concerned about applying Werktreue ideals to operetta, returning to original versions and removing interpolated numbers or other changes made in previous English-language versions. I remember one person I met during OLO’s summer season complaining with a degree of outrage that Kosky had cast a male singer in the title role of Dostal’s Clivia.

But was “truth to the work” ever a maxim that operetta directors of the past followed? There was nothing curatorial about Erik Charell’s revival of Die lustige Witwe in Berlin in 1928. You may know that English National Opera has been experiencing grave financial difficulties. Why, I ask myself, do they not contemplate producing some operettas à la Kosky? The home of the ENO is the Coliseum, where White Horse Inn had its West End premiere in 1931 and played continuously to capacity audiences for over a year. I certainly hope the Leeds conference will make British theatres think more about the possibilities that operetta offers.

Prof. Derek B. Scott from the University of Leeds. (Photo: Private)

Not too long ago the V&A Museum in London presented a successful opera exhibition. Is there a comparable operetta exhibition in sight somewhere? (There were very popular shows at Theatermuseum Wien and even – of all places – at Schwules Museum Berlin.) Is it time for a British or major American based operetta exhibition? (After all, these countries were key players in operetta history.)

You may know that the London Theatre Museum closed, and much of what it contained passed to the V&A. They do have many designs for operetta costumes by famous designers such as Comelli (who also did a lot of work for the Royal Opera House). I would very much like to see an exhibition of their material related to operetta, but I’m not holding my breath!

I wish the Shubert Archive in New York would mount an operetta exhibition, given the material they have relating to the many operetta productions produced by the Shubert brothers. However, the space at the Lyric Theatre is limited.

The University of Leeds.

Can anyone come to your conference? Is there an attendance fee? Will some talks be made available as live streams? And: will you publish the talks afterwards, so that there might be a new English language book for all those who are tired of Operetta: A Theatrical History?

The conference is open to anyone who registers. The registration site will be advertised in November, and the attendance fee is £10 a day (waged) or £5 a day (unwaged, such as students, or the retired). The fee is being charged solely to help cover some of the cost of the provision of refreshments. I am asking about the possibility of live streaming, or recording of sessions, but I have not had any answer yet about whether this will or will not happen. Cambridge Scholars Press has written to me expressing an interest in publishing the conference proceedings.

Nazi star composer Rudolf Kattnigg, who wrote “Prinz von Thule” and “Balkanliebe.” (Photo: Universal Music).

Your final discussion round is dedicated to “Operetta in Nazi Times: Aryan Sex and Syncopations for the Master Race 1933-1945.” Politics have not exactly been at the forefront of recent operetta research in English. Even though Nazi politics/history are an eternal hot topic in the English-speaking world as well. Why have English researchers of the past turned a blind eye on this? And how do you thing a discussion about “Aryan Sex and Syncopations for the Master Race” will go down with students in Leeds? (Or your fellow professors at the university?)

This final session is a wonderful example of the unexpected re-evaluation of operetta that the conference is encouraging. English musicologists have generally shied away from music and politics, and when they do examine politics it is often in the context of a particular composer (the favourite being Shostakovich). Music of the Nazi period, in particular, has been found too awkward and embarrassing to delve into (although the work of Erik Levi is a notable exception). I’m sure that students will flock to this final conference presentation, but I’m also sure that if they come along expecting something along the lines of Springtime for Hitler they will surprised.

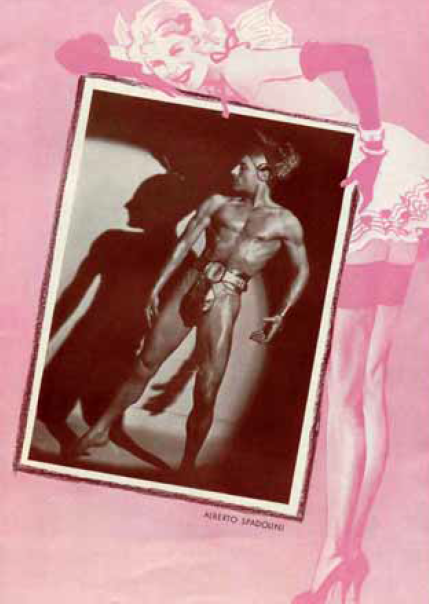

A pretty lady in pink holding a photo of Alberto Spadolini in the “Lustige Witwe” program book, 1940. (Photo: Atelier Alberto Spadolini)

Similarly, if any of my professorial colleagues suspect this session may contain some humour “in poor taste”—especially given the large Jewish music archive project with which some of them have been involved—then they will soon discover that laughter can be an excellent means of provoking critical thought, as Walter Benjamin pointed out.

For more information on the conference, click here.