Alyce Mott

VHSource (LLC Alyce Mott)

14 March, 2016

Who were the truly instrumental people who caused America to develop the largest and most influential entertainment industry in the world, and why, if you can’t name them quickly, have they been almost totally forgotten? We like to call these folks the “game changers.” Someone once said … “there are hundreds of people who have helped shape who we are now.” Many sources maintain that no real development took place until 1927 and the opening of the Kern/Hammerstein II musical Show Boat. Both those observations never rang true with us. We kept running across individuals whose talents served tens of thousands of people at a time. Orchestras and bands routinely played to audiences numbering in the tens of thousands. Yes there were thousands of composers (men and women), hundreds of arrangers, hundreds of music publishers – all enjoying the fruits of a huge industry predating 1927. But who really led the way? Thousands never spring from nothing.

Original sheet music cover for the 1927 hit “Show Boat.”

We met G. Schirmer – America’s oldest classical music publisher and Witmark & Sons who almost singlehandedly built the popular/theatrical music publishing industry. Perhaps Malcolm Gladwell examines it best in his book the Outliers, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2008 when he looks at today’s “giants and how they came to be.” Gladwell looks at Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and the Beatles and calls them “outliers.” For Gladwell, outliers are “those people whose achievements fall outside the normal experience.” He is fascinated by what makes such individuals so successful just as we are fascinated by the same type of individuals pre-1930. The only difference is we have always called them “game changers.” They are those folks who first stepped down a certain path because of education, passion and being in the right place at the right time. Game Changers not only led the way for others to follow, but made the road easier.

These folks lived and flourished pre-1930. They were American household names before recordings, film, and television were even glimmers in their inventor’s eyes. Thus they were household names because they traveled the country bringing their particular passion to the people in such a way that they became the light to follow, the steps to walk in, and the model to emulate. The record of their existence is almost nonexistent except in early books (1950 and earlier), although there are some new biographies being undertaken. The amount of space provided them in text books is minuscule compared to those coming after them. Pre-1950 authors recognized a giant when they saw one and recorded the lives for posterity by talking to the individual if they were still with us and if not, finding those who knew them. Magazine and newspaper interviews also provide insight into these people. However, because they did not record and almost no performance records exist beyond printed programs, they have faded from culture’s memory into oblivion.

What is the VHSource definition of a Game Changer? It’s an individual who makes such a huge contribution to the evolution of their particular passion that without them, growth would creep rather than soar.

Game changers inspire “copy cats” who help speed up the evolution and we don’t mean “copy cats” in a bad way at all. They are simply folks who say to themselves – “Yes! That’s the way it should be – that’s the way I will do it, too.” Game changers do it first and stunningly well. Everyone else follows along and may very well become tremendously famous for their own achievements. However, when truth shines its light, the majority of famous souls are not necessarily those who made it possible.

In exploring various topics and questions, VHSource found that America had such giants, and even more importantly, those giants were the foundations on which the entire modern entertainment industry has always stood. They were the platform on which hundreds of admittedly very talented, famous folks built. Someone laid the concrete for that platform out of passion, vision and being themselves. The fascinating fact is that the majority of America’s Game Changers lived, created and “changed the game” before the advent of any sort of archival recording – either aural or video. We cannot “see” or “hear” their genius. If any such records do exist, they are almost always scratchy, hard to listen to, grainy to look at and certainly not representative of the actual performances.

We became fascinated by these people as we read and searched for answers to other questions. These names would come up over and over again until we searched out writings by the actual people talking about their own lives as well as excellent and not so good books examining the lives of these “Game Changers.” The constant thought was “why don’t we know about these giants – our forgotten heroes.

We have chosen the following individuals to explore in more depth this year: Theodore Thomas, George M. Cohan, Oscar Hammerstein I, Victor Herbert, D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, and Oscar Hammerstein II.These men and the one woman all lived and did the majority of their work (exception the last two listed) between 1830 and 1930. We’ve included Hammerstein II simply because there is no doubt that he was the first great American musical librettist – not the most prolific – but definitely the finest. Hammerstein II’s play writing career was also well underway by 1930. The team known as Denishawnalso did the majority of their work together after 1930, but the team was in place well before that date.

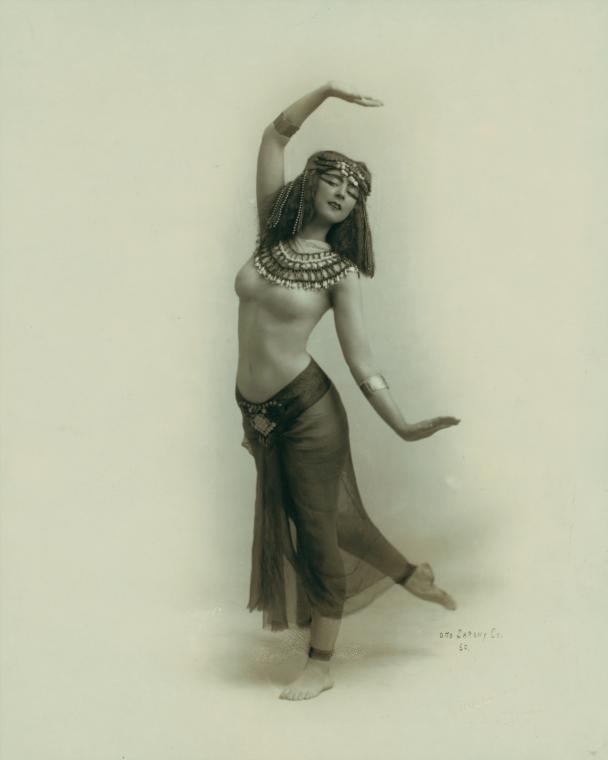

Ruth Saint Denis began to investigate Asian dance after seeing an image of the Egyptian goddess Isis in a cigarette advertisement, 1910.

In addition, Ruth St. Denis had such audacity in 1896 that you definitely need to know this woman. We know there are many, many of your favorite historic theatrical, musical, and dance favorites who cannot be found on the rather slim list above. The question to always ask yourself is “did you favorite actually change the Game?” If you can make a case of a missing individual, please let us know.

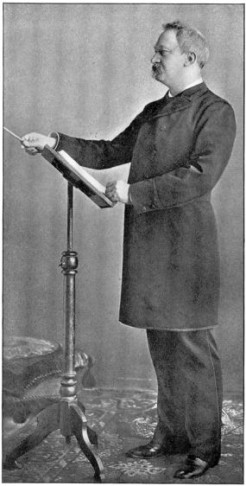

Conductor Theordore Thomas.

Let us begin with the earliest almost totally forgotten giant Theodore Thomas (1835-1905), considered to be the “Father of the American Orchestra.” This towering figure was primarily the conductor (leader of an orchestra) of his own Thomas Orchestrafrom 1862 to 1889 (28 years). The Thomas Orchestra was the only privately funded salaried American orchestra during those years. The orchestra members had two weeks off each year and their salaries came out of their conductor’s pocket. It had no board and no guarantors. While it was based in New York City, beginning in 1869 it began touring America along what became known as the “Thomas Highway” from the East Coast to the West Coast and as well as North to South. This orchestra often played to audiences of 10-20,000 people and it’s fairly normal numbers of 80-100 musicians were frequently augmented by local musicians to a size of 300 or more in concert. Theodore Thomas set out to educate the citizens of America wherever they might reside to “good” music, championing the likes of Bach, Beethoven, Berlioz, Bizet, Brahms, Cherubini, Dukas, Dvorak, Gounod, Grieg, Mozart, and the newcomers Liszt, Massenet, Mendelssohn, Rubenstein, Saint-Saëns, Schubert, Schumann (both Georg and Robert), Sibelius, Smetana, Strauss (both Johann and Richard), Tchaikovsky and Wagner. These are just a few of the more famous names out of 146 composers Theodore Thomas premiered and championed in America.

Overseas, Thomas was so well known and admired that composers sought him out whenever he crossed the ocean to Europe with their scores in hand, hoping he would add them to his repertoire. Along the way Thomas founded many of the institutions you know today, conducted every major orchestra you know today and owned the largest orchestral library in the world. All he ever really desired was a permanent “hall” or “home” for his orchestra. He finally got one and unless you have read all of these newsletters fairly closely, you will most likely not guess what city constantly ignored him and where that permanent hall is as well as why and when it was built. (It is still used today to house the major American orchestra for which it was built.)

Theodore Thomas was a household name across America and thus, her first true superstar, and our first Game Changer explored in depth in February.

Cohan and his sister Josie in the 1890s.

George Michael Cohan (1878-1942) was known variously as “The Prince of Broadway, The Father of Broadway or the Man Who Owned Broadway”, and like the Pied Piper, Cohan led the way from vaudeville to the creation of the genre known as musical comedy. Along the way he would be a dancer, an actor, a singer, a composer, a librettist, a lyricist, a playwright and a producer. Born into a vaudevillian family – The Four Cohans – the baby literally grew up on stage performing every night in his father or mother’s arms with his sister. It was the young teenage Cohan who began writing his family’s material and extending those vaudevillian skits and sketches into longer and longer pieces until a story plot filled a whole evening and early musical comedy was born. Because his roots were extended deep into vaudeville, the quality of music was rough, fun and aimed directly at the enjoyment of the common man. There was little refinement in his work. Cohan left that to the operetta world. He spoke both for and to everyman, while creating a whole new genre out of the aging bones of vaudeville which had done the same thing rising from the minstrel show. His purpose was to bring fun and entertainment to anyone with the nickel to come in the door. He wrote, composed, produced, and appeared in more than three dozen Broadway musical comedies. He composed over 500 songs and was one of the initial 150 members of ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.) George M. Cohan was definitely a Game Changer.

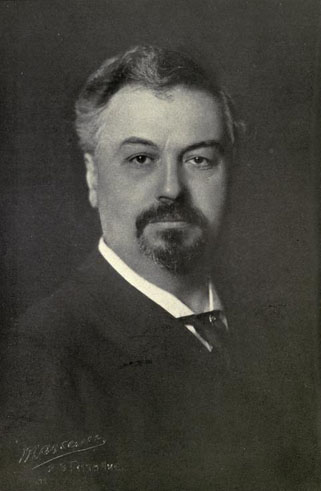

Portrait of Oscar Hammerstein I, from “Who’s Who on the Stage,” 1906.

Did you ever wonder where all those Broadway theatres came from and why they landed in or near Times Square? One need look no further than Oscar Hammerstein I (1847-1919), possibly one of the first truly eccentric characters Broadway has known. According to great great grandson, Oscar Andrew Hammerstein in his new book, The Hammersteins, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, NY, 2010, Hammerstein I was an inventor, a writer, an editor, a publisher, a composer, a speculator, a designer, a builder, a promoter, a showman and an impresario. However, Hammerstein I is an individual whose greatest contribution to the foundations of New York Theatre was the designing and building of his eleven New York physical theatres. He also managed to design and build a Philadelphia Opera House and a London Opera House. Each one was acoustically perfect and suitable for opera and built between the years 1889-1914. It was Hammerstein I who felt the expanse of Long Acre Squarewas the perfect location for multiple theatres and built the Victoria, the Hammerstein Roof Garden (on top of the Victoria), the Olympia (actually 4 theatres within one), the Republic, the Lew Fields Theatre, around and near this piece of land in what would become mid-town Manhattan. The land itself renamed Times Square officially in 1904, after the New York Times opened its new headquarters on the West side of the square, would become known as the Crossroads of the World. As recently as 2011, Travel + Leisure magazine named Times Square as the world’s most visited tourist attraction, bringing in over 39 million visitors annually.

In addition, Hammerstein I built two different Manhattan Opera Houses on 34th Street: the first in 1893 where Macy’s now stands, and the second in 1906 which still stands today as the Hammerstein Ballroom between 8th and 9th Avenues. Hammerstein I, the builder of opera houses, did not stop with the physical edifices. His greatest achievement in his own eyes would have been the founding and operation of the Manhattan Opera Company (1906-1910). The opera impresario hired some of the world’s most famous singers – Nellie Melba, Mary Garden, Luisa Tetrazzini, Emma Calvé, Maurice Renaud, Charles Dalmorès, Mario Sammarco and John McCormack. This organization had the distinction of being the only American opera company to effectively challenge and compete with the Metropolitan Opera Company, but also to come very close to putting the grand old lady out of business. This relatively small (5’4″) man – forever clad is his morning suit, the highest heel a man could wear, the tallest stove pipe hat money could buy and an ever lit cigar – was larger than life and a force to be reckoned with from the moment he arrived in New York City until his death in 1919. He lived his life constantly in a “always on, fast forward” position, passionately serving Grand Opera in American in any way he could, and thus, definitely a Game Changer.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) became the first full time film director to make a motion picture – the 17 minute In Old California– in “Hollywood.” Griffith began with the Biographfilm company when it was based in New York City, and was the sole director working for the company in 1910. Griffith would literally invent today’s common term “close-up” and take rhythmic editing, parallel action, and dramatic lighting far beyond the occasional uses they had been put to previously. Griffith directed 60 films during his first year with Biograph in 1908 and ended in 1931 with one film credit. Along the way he was the director of record for more than 450 films before he produced the Birth of a Nation(1915). This film is considered to be the first blockbuster feature length film (12 reels), earning millions of dollars in profit. While he co-founded United Artists with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., and Charles Chaplin in 1919, Griffith was to be forever tied to the “bigotry” and offensive celebration of the Ku Klux Klan as portrayed in Birth of a Nation, based on the 1905 book The Clansman by Thomas Dixon. One of the D. W. Griffith most prolific directors during the birth of the huge American film industry would create only 45 more films before his death in 1948 with the last being in 1931. No less than John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Cecil B. DeMille, Jean Renoir, King Vidor and Sergei Eisenstein all named Griffin as their most important influence. Charlie Chaplin called Griffith “The Teacher of Us All” – certainly worthy of the label a Game Changer.

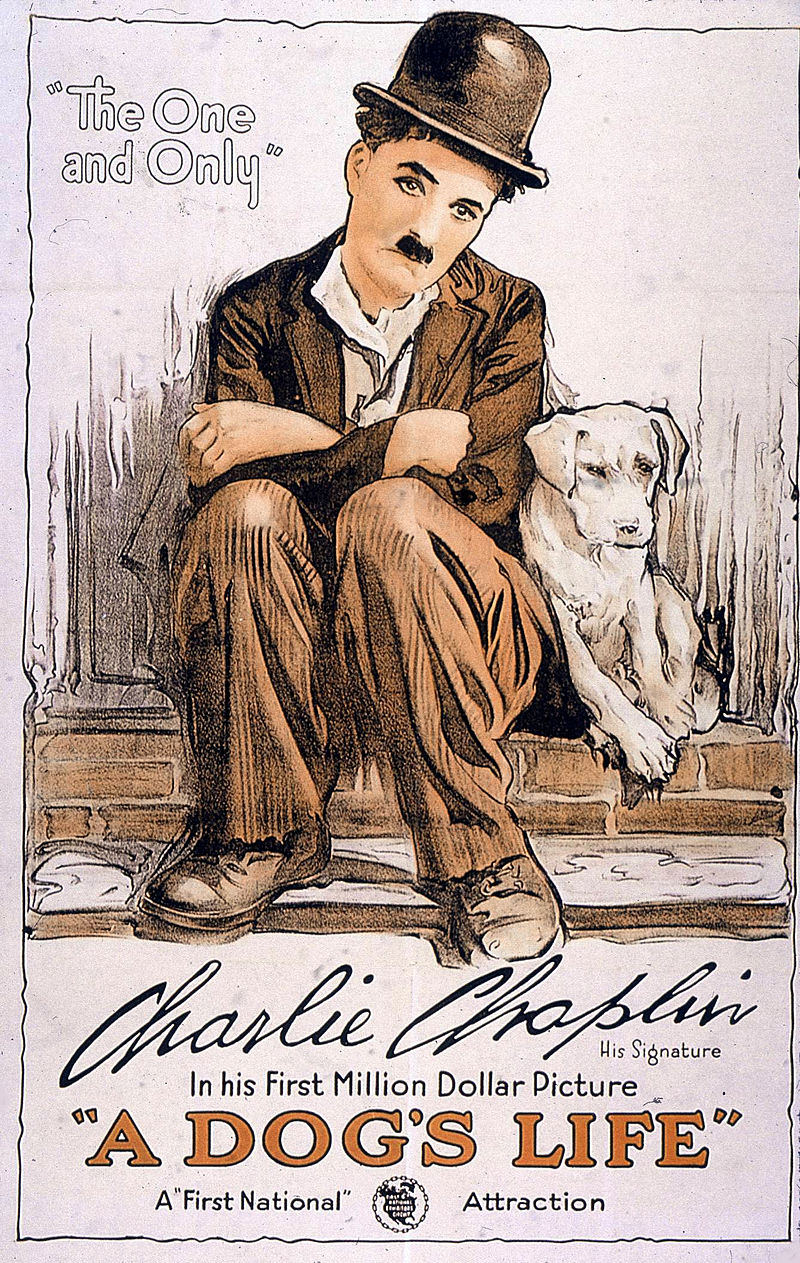

Poster for “A Dog’s Life” (1918). It was around this time that Chaplin began to conceive the Tramp as “a sort of Pierrot”, or sad clown.

Speaking of a giant Game Changer in the film industry, the name of Sir Charles Spencer “Charlie” Chaplin (1889-1977) must certainly arise. While Chaplin was an English comic actor, it was his American work as a film actor, film director and composer during the silent film era that elevates Chaplin to the title of Game Changer. Chaplin’s film career earned him the title of the First International Movie Star. There was no place in the world to which Chaplin could travel without being recognized. He earns the Game Changer title partly because of this international stardom, but also because he became one of the first film actors to rise into producing and controlling every single aspect of his own films.

We have already mentioned that he was one of the founders of United Artists. His initial skills were in the areas of mime, slapstick and other visual comedy routines, but few remember that he also played the piano and the cello.

In the late twenties when talkies and their synchronized sound tracks were beginning to show vast improvement, Chaplin responded by creating “City Lights” (1931) a silent film with a music sound track composed entirely by himself.

He always felt that the silent film was the true art form, and the talkies added nothing of real value. George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) who often had a very low opinion of many things, surprisingly called Chaplin “the only genius to come out of the movie industry”. Chaplin is truly worthy of much further exploration as a Game Changer.

Ruth St. Denis.

Ruth Denis (1879-1968), our only female on the list, was initially trained in movement by her mother using exercises developed by the Frenchman François Delsarte (1811-1871). These exercises were actually one of the first acting systems teaching actors to communicate their emotional interior to the audience through gestures and movement. Denis spent years practicing the Delsarte poses before getting a job as a skirt dancer for Worth’s Family Theater and Museumin New York City in 1894. According to Wikipedia, a skirt dance was “a form of dance popular in Europe and America, particularly in burlesque and vaudeville theater of the 1890s, in which women dancers would manipulate long, layered skirts with their arms to create a motion of flowing fabric, often in a darkened theater with colored light projectors highlighting the patterns of their skirts.” Denis then toured with producer/director David Belasco(1853-1931) where she acquired the stage name “St. Denis.” However, in 1904 St. Denis happened into a drugstore in Buffalo, NY where she saw an advertisement for Egyptian Deities cigarettes. This image caught the dancer’s imagination and blossomed into a passion for oriental philosophies and mysticism. In 1905, she left Belasco to become a solo dancer exploring these ideas. Something unheard of for a woman!

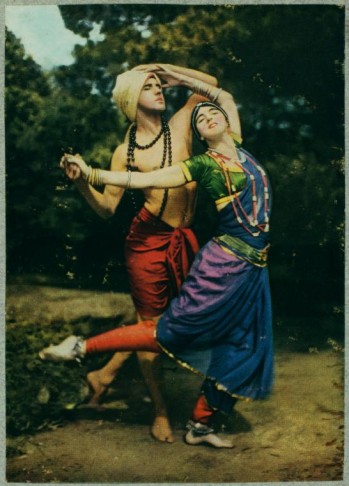

Ted Shawn with dancer and wife Ruth St. Denis in 1916.

In 1911, dancer Ted Shawn happened to catch one of St. Denis’ performances and fell madly into artistic love. By 1914, Shawn was St. Denis’ student, then her dancing partner and finally her husband. Together these two passionate people founded Denishawn. The school/company quickly became the “cradle of American modern dance.” Today this probably seems like a relatively small deal to a dance obsessed American public. But in the dance world of 1915, there were only classical ballet schools and the self-taught tap dancers of vaudeville and early musical comedy. Ziegfeld’s girls primarily paraded elegantly in lovely costumes. Broadway dance stars were normally couples such as Vernon (1887-1918) and Irene (1893-1969) Castle whose forte was ballroom dancing. For St. Denis and Shawn to found a school for dance as a pure art form outside of the boundaries of classical ballet and theatre was earth shattering. Denishawn trained such giants as Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Lillian Powell, Evan-Burrows Fountaine and Charles Weidman as well as silent film star Louise Brooks. The pair were also the founders and owners of a legendary dance festival, Jacob’s Pillow begun in 1930 and still functioning today. This pair and this lone female in our exploration were huge Game Changers in American dance.

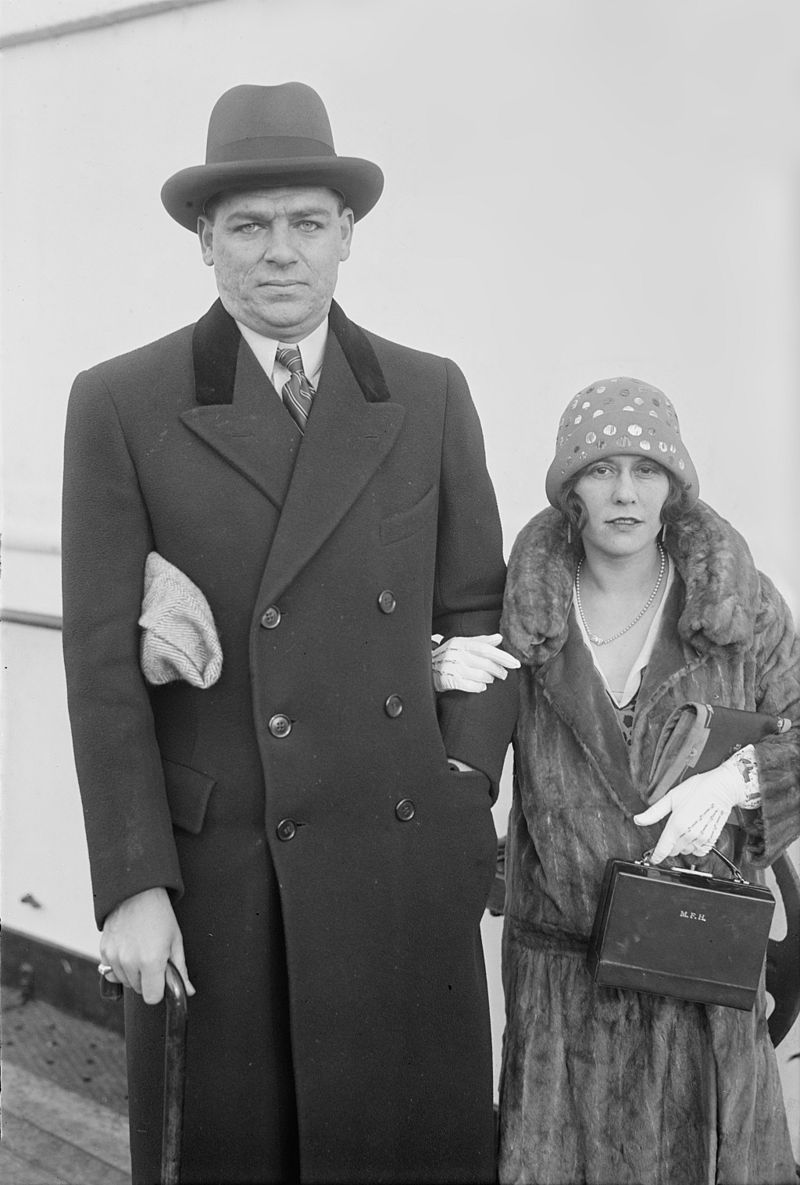

Hammerstein with his first wife, Myra Finn, photographed aboard a ship.

VHSource elects to include Oscar Greeley Clendenning Hammerstein II (1895–1960) because he truly was the first great American lyricist/librettist who brought sound storytelling, logical plots, and great character creation to the musical comedy world. You have read the names of Harry Bache Smith, Henry Blossom, and Rida Johnson Young often in these pages. Smith was certainly the most prolific American librettist/lyricist to ever work on Broadway – 300+ produced Broadway works and 6000+ song lyrics. No single individual including Hammerstein II has ever even come close to Smith’s output, but did he change the game? No. His librettos were often said to be the weak link in huge numbers of productions. In truth, Smith’s lyrics were his true forte. Henry Blossom and Rida Johnson Young told better stories that Harry B. Smith did, but none of their works ever reached the sophistication of Show Boat.

There was a team who could count as early Game Changers in the libretto/lyric category if they had been American. Brits Sir Pelham Grenville (P.G.) Wodehouse (1881-1975) and Guy Bolton (1884-1979) began moving the literary side of Broadway forward in their work with Jerome Kern (1885-1945) on the Princess Theatre Musicals (1915-1919), but again, Wodehouse was a Brit and while these scripts were great beginning shifts, they also never rivaled Show Boat. Clearly the game changer in “words” was Hammerstein II. One finds that he started in 1921 in collaboration with Otto Harbach (1873-1963), penning such huge hits as Rose Marie with music by Rudolf Friml and The Desert Song and The New Moon with music by Sigmund Romberg.

The bottom line is that Show Boat became such a Game Changer that it has made academia forget everything that went before on Broadway. Hammerstein II did this masterpiece libretto/lyrics all by himself. When he teamed with composer Richard Rodgers, the rest is history.