Michael Hardern

Operetta Research Center

21 February, 2020

It’s mind boggling that the entire operetta repertoire created and performed in the former DDR between 1949 and 1990 has been ignored by researchers in the West. Not a single operetta book – apart from the titles published in the German Democratic Republic itself by Otto Schneidereit –mentions these works, not even their mere existence. Volker Klotz in his famous Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst discusses “good” and “bad” operettas from all over the place (Spain, Italy …), but no works written for the “other” half of Germany. And the new Cambridge Companion to Operetta has chapters on operetta in Russia/USSR and Nordic Countries, among other places, but has German history “stop” after the Nazis.

Various famous operettas from Eastern Germany, as presented on an LP cover in the GDR.

Maybe history always skips a generation, as curator Wolfgang Theis recently said in an interview. For the immediately following generation events and developments are “too close,” causing a reaction of casting them aside as old-fashioned and uninteresting, oppressive even. That’s certainly what happened after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 and the unification of East and West Germany began. Many things associated with the old “socialist” system were pushed aside, because they were seen as negative. Many spoke of the DDR and it’s omnipresent Stasi (State Security) surveilance system as a dictatorship and a horror. Which it was, for many.

As part of this reaction, the many shows written for the theater scene in the DDR were pushed aside, too. One of the few exceptions was Peter Lund’s production of Messeschlager Gisela (1960) at Neuköllner Oper in West-Berlin, in 1997. Though it was well received, and even recorded, there was no wave of new interest, let alone a new wave of productions.

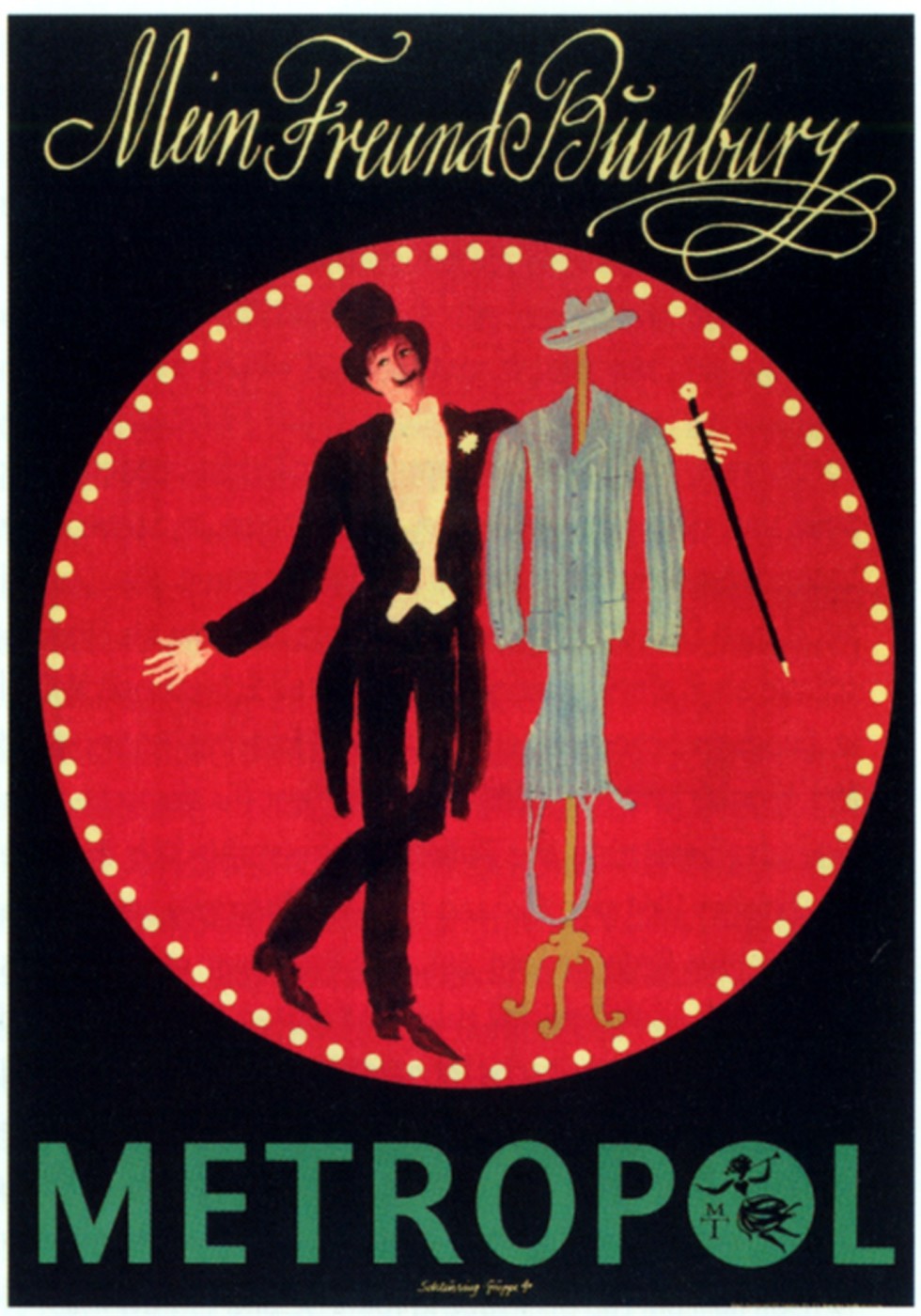

The many once celebrated titles by composers such as Gerd Natschinki (Messeschlager Gisela, Mein Freund Bunbury), Guido Masanetz (In Frisco ist der Teufel los), Herbert Kawan (Treffpunkt Herz) or Eberhard Schmidt (Bolero) disappeared in archives, the various recordings that had been released on LP in DDR times were not re-issued as cast albums on CD. Not a single one of them. Only recently have some enthusiasts put them onto YouTube, making the music available again to a larger public again and saving it from total obscurity.

A year ago, at an operetta conference in Leeds, various younger researchers presented talks on the political side of the genre in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and the German Democratic Republic. The universities of Leipzig and Halle have meanwhile installed departments devoted to analyzing and preserving the forgotten works of post-WW2 German language operetta from the East.

The only other place where DDR operettas were included was the exhibition Welt der Operette at Theatermuseum Wien, in 2012. The catalogue has an essay by Roland Dippel on the topic. When that exhibition moved to Munich, the local director of the theater museum chucked out the DDR section claiming it was irrelevant for operetta history in Germany. Instead, a new section dedicated to Johannes Heesters was included.

Classics vs. Working-Class Heroes

In West Germany, operetta performances after 1950 focused almost exclusively on the “classics” and revivals of standard works from the 1910s to 1940s, there were hardly any new operettas written. Eventually the genre became a dead art form.

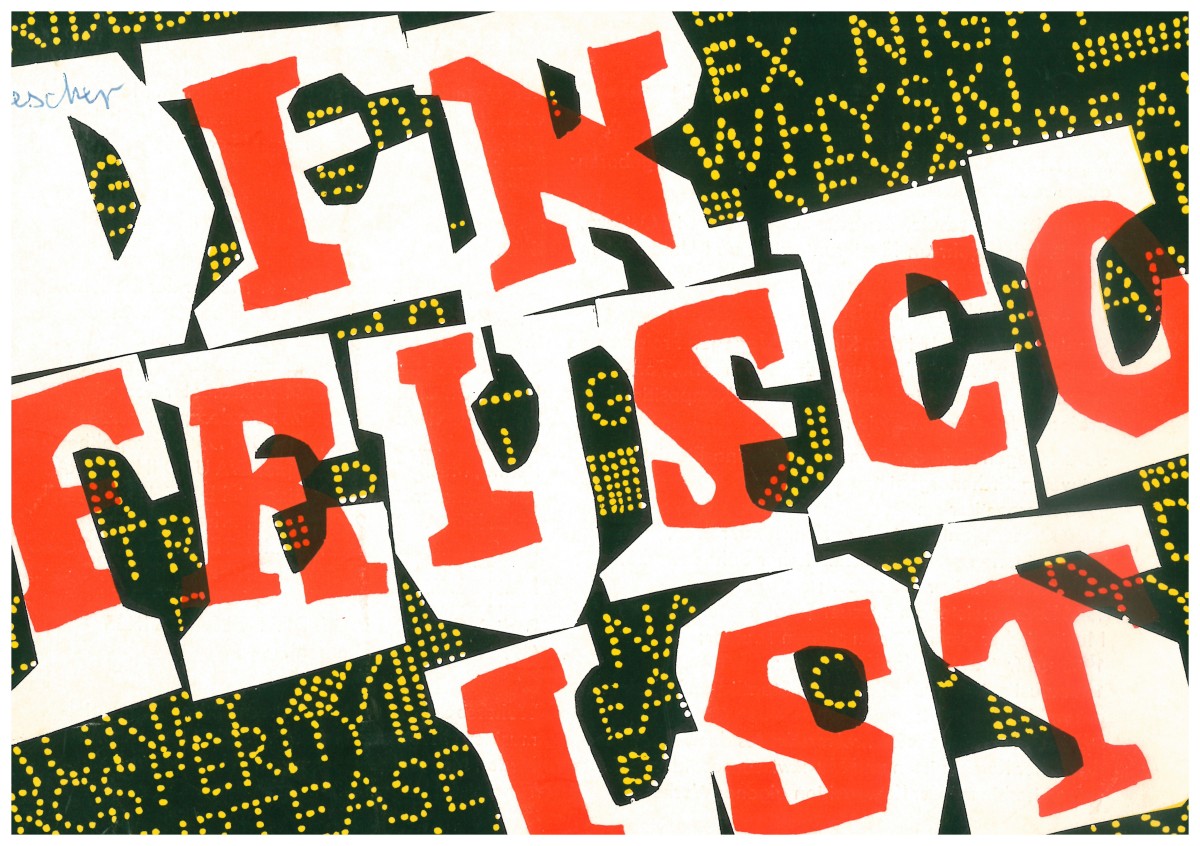

Cover of a program for “In Frisco ist der Teufel los” from 1965. (Photo: Archiv of the Operetta Research Center)

In the DDR the opposite was the case: authors were asked to create novel works that reflected the new and improved “realities,” presenting working class heroes, celebrating sexual freedom and gender equality, criticizing capitalism, imperialism, fascism etc.

The result were works such as In Frisco ist der Teufel los, showing how harbor workers in San Francisco are treated by corrupt US-American corporations. In the end, these workers unite to form a union and overturn corruption, leading the way to a better future. Masanetz wrote a rather “American” style score that made it possible for people in the DDR to enjoy the latest musical trends, in a recycled version. Because often theaters in the East were no able or willing to pay the royalties for “real” American hits.

Since many shows from the 1910s and 20s were also still under copyright and thus expensive to perform, they were labeled “late bourgeois” or “late capitalist,” i.e. ideologically problematic. Shows that had premiered during Nazi times were completely taken out of the repertoire, at least until the 1980s when things changed and the DDR was in a deep crisis which eventually led to its collapse.

Poster for “Mein Freund Bunbury” at the Metropol Theater in East-Berlin, 1973.

These many shows – Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten (1970) and Geld wie Heu (1977), Heute Nacht kommt Conny (1968) or Aphrodite und der sexische Krieg (1986) – are now part of a concert put on by Semperoper Dresden. On Sunday, February 23, the company presents a matinee entitled “Gisela, Frisco, Bunbury …” Heiteres Musiktheater – Musikszene DDR.

The concert will be recorded by MDR and broadcast later.

As a special guest Maria Mallé, an actress and cabaret singer who was in the ensemble of East-Berlin’s Metropoltheater for many years and actually performed many of these shows under the direction of the composers, will appear on stage in Dresden. She will talk about her personal experiences with these works. Together with Dr. Kevin Clarke (from the Operetta Research Center) she will guide the audience through this repertoire – that seems to be reawakened from its 30 year long beauty sleep.

Unique Political Context

You don’t have to actually “like” this music and the lyrics, nor the plots and recordings. But they give testimony of a flourishing operetta scene in a unique political context, where audiences had to pay particular attention to subtext for political criticism that was officially not tolerated. As such, these shows and their reception during four decades up to 1990 deserve to be acknowledged as part of general German history and the history of German language operetta in particular.

The concert in Dresden is a good place to start. It has been put together by conductor Johannes Wulff-Woesten and dramaturg Johann Casimir Eule.

For more information, click here.

The concert will be broadcast on MDR-Kultur Radio on 11 April at 8.05 pm.

For an example of how difficult it was to get hold of foreign currency, one of the most popular series of films in the DDR was the Danish Olsenbande series. On one particular occasion (I forget which) East German TV wanted to invite the stars to be part of a special programme they were putting together. Payment in cash was totally out of the question, so instead negotiations came down to how many cans of caviar they were prepared to accept.

MDR does a good job in keeping alive a lot of East German culture. I’ve seen an interview with Chris Doerk where she bemoaned the fact that the only thing most interviews with her wanted to talk about was the Stasi, so I can understand why Natschinski wanted to keep out of that.

Here’s a direct link to the programme on the web. I hope it’s not personalised or time limited https://www.mdr.de/kultur/radio/ipg/sendung-547004_date-2020-04-11_days-true_ipgctx-true_zc-daabe4d7.html