Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 December, 2020

Recently, Wolfgang Jansen published a collection of essays dealing with “Popular Music Theater under Socialism,” an aspect of 20th century operetta and musicals overlooked for years by researchers in the West. In his review of the book, Kurt Gänzl even asked why anyone in the West should bother with shows created behind the Iron Curtain? Of course, these shows mirror the realities of a great many people living under Socialism and Communism for decades, these are also shows many people saw, shows that were part of their lives, with scores that were the soundtrack of their existence. To brush all of that aside as “unimportant” from a Western point of view is… well, rather shortsighted. We spoke with Maria Mallé who was a celebrated soloists in the ensemble of Metropoltheater in East-Berlin from 1969 onwards. She talks about the dramatic changes that occurred after the Fall of the Wall in 1989/90 and about why the once popular DDR shows were completely erased from the repertoire. The story she tells is typical of what happened in other collapsing former “Eastern Bloc” countries.

Wolgang Jansen’s “Popular Music Theatre Under Socialism.” (Photo: Waxmann)

Hello, Maria. There’s a sudden new interest in “Heiteres Musiktheater der DDR,” i.e. operettas and musicals created in East-Germany between 1949 and 1989 to reflect the new Socialist realities. Why such a revival now?

I think this new and fresh approach to “Heiteres Musiktheater der DDR” is the result of the many things that happened in 2020 in the context of “30 Years of German Unification.” People have started rectifying things that had been unjustly overlooked for three decades because of wrong evaluations and misguided remembrance of the past. I noticed this in various areas of life where things have suddenly been dug up again, in an opulence that makes me a little cautious. Nevertheless, it’s great that this is finally happening.

When the Berlin wall came down in 1989 the repertoire of Metropoltheater changed almost overnight. The once celebrated DDR titles disappeared…

After 1989/90 we hardly played any DDR musicals anymore. And certain operettas, that had not been performed in DDR times because of royalty problems or anti-Fascist political considerations suddenly appeared in the repertoire, e.g. Hochzeitsnacht im Paradies which Johannes Heesters had originally premiered during Nazi times. Before 1989 such a work would have been unthinkable on our Metropoltheater stage, because it was considered “contaminated.” But suddenly such considerations seemed irrelevant. On the other hand, the more recent DDR past was deemed “taboo.”

Maria Mallé in her Berlin apartment in 2020. (Photo: Private)

What happened with the performance material of the shows that were now taboo?

Everything was shoved into the dumpster. Hans Dieter Arnold, the last Chefdramaturg of Metropoltheater, told me of conversations he had with representatives of the East-German Henschel Verlag, which distributed DDR musical theater material. They tried to negotiate with West-German publishers such as Bärenreiter and Schott to take the material into their catalogues. But no one was interested. Klaus Eidam from VEB “Lied der Zeit”, another DDR publisher, tried the same and couldn’t prevent that everything went straight into the trash containers. No one wanted the materials of 50 years of musical theater history. The system change of 1989/90 was an ideal opportunity to erase all these shows from collective consciousness.

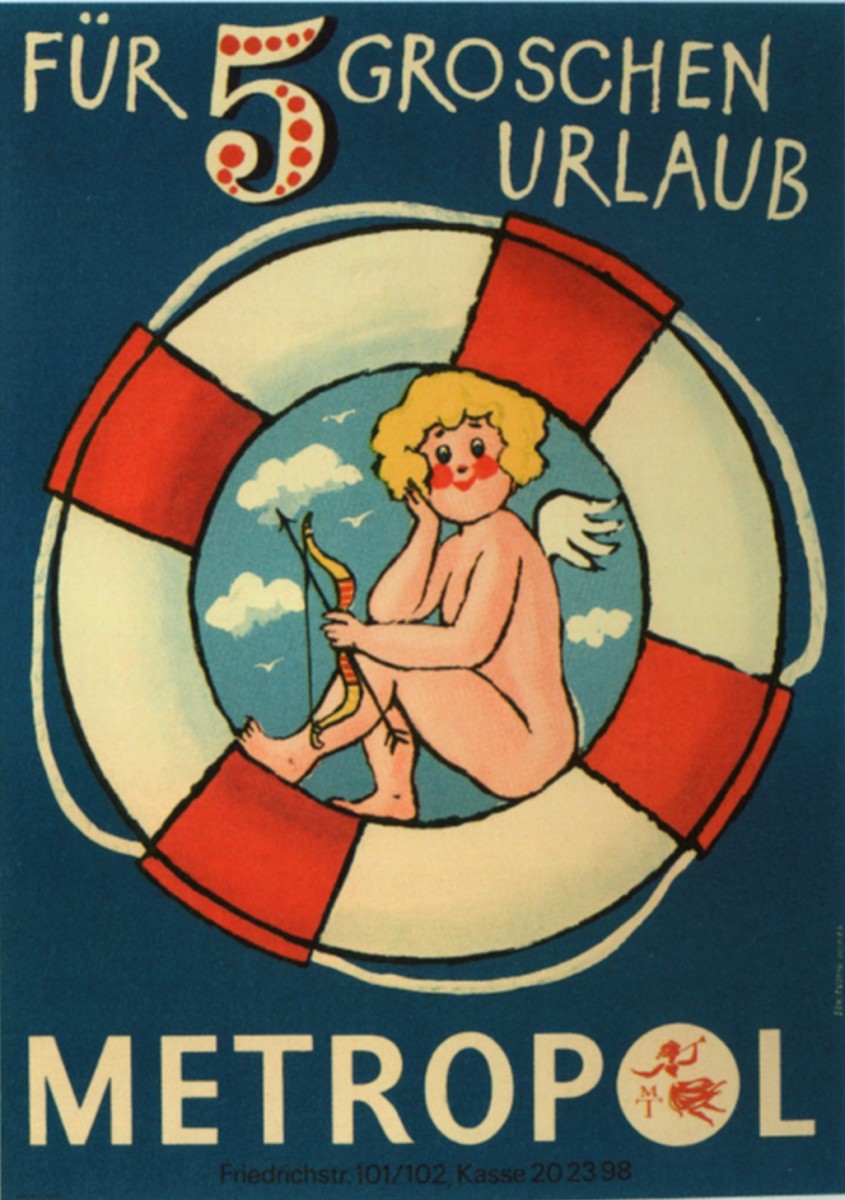

Poster for Horst-Ulrich Wendler’s “Für 5 Groschen Urlaub” (“Holidays for 5 Cent”), Metropoltheater 1969.

Could you compare such “erasure” to what happened with architecture in East-Berlin?

Everything had to go. There’s hardly anything left of the famous architectural monuments from DDR times. Not just the wall was torn down immediately, but also the Palast der Republik was declared contaminated with asbestos. No matter how many people took to the streets to demand that it should stay where it was, as an object of identification for many East-Berliners and those who had come to the capital of the DDR. It was one of the most modern buildings in the country, an important entertainment venue. But because it was also the seat of the “Volkskammer” it was seen as a political issue. And had to go, because supposedly the asbestos problem couldn’t be solved, while the monstrous ICC in West-Berlin is still there in 2020, with just as much asbestos. It’s laughable how the population of the former DDR was treated like idiots with such explanations.

The (in)famous Palast der Republik in 1986. (Photo: Jörg Blobelt / Wikipedia)

What would you consider interesting about DDR popular musical theater – or from other Socialist and Communist countries – for people from the West?

This whole genre represents 50 years of life lived behind the Iron Curtain, by artists as well as by audiences. This arrogance of not caring about this in the West has spread to so many areas. The other way round things had always been different. In the East we knew what was going on in the West, certainly when it came to culture. My colleagues in the theater were aware of what was being performed in the West, and how, and by who. While those in the West had basically no idea of what happened in the East, which became very evident after the “Wende.” Agents and theater director treated once famous East-German stars like mere nobodies and forced them to do ridiculous castings for stupid little roles. And these former stars had to play along to get any kind of job, so they could pay their rent.

A vintage LP with some of the greatest hits from the DDR, including “Mein Freund Bunbury”.

Where do you assume such Western arrogance stems from?

We always said about our West colleagues that they had the “fat wallet.” And that gave them a view of the world which created such a situation after 1989/90. And not much has changed since. Which is why I am thankful for anyone who bothers to question this attitude and re-think developments of the past.

Did the ensemble at Metropoltheater change after 1989/90?

The ensemble stayed mostly the same. But a few positions in the management were exchanged, because they were considered too closely associated with politics. As a result, some people were wiped away, including the artistic director of the company, Peter Czerny. There was no public discussion about this, not even within the ensemble. It just happened. And it was silently accepted by everyone, assuming there must be reasons for these changes, even if no one ever directly asked about them.

Who followed Mr. Czerny?

A search for a new director began, but no one could be found. So in 1991 the former co-director from DDR times, Werner P. Seifert, was made interim director, a position he held until 1995 when René Kollo took over the theater and company.

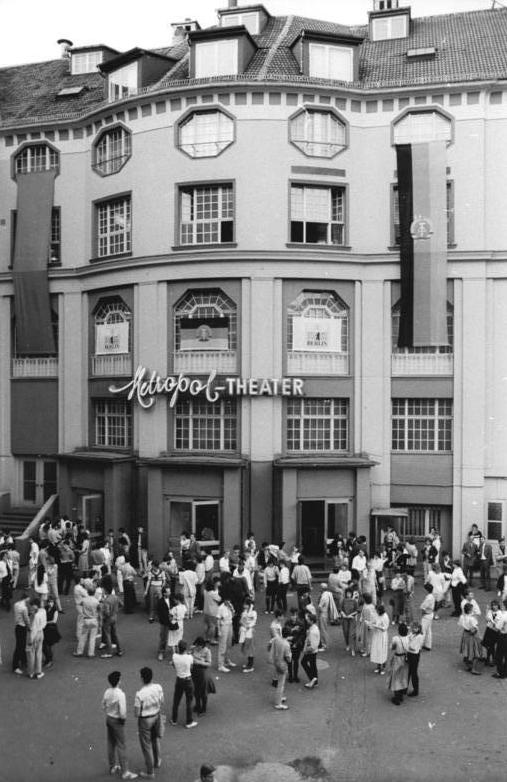

The entrance to the Metropoltheater in East-Berlin, 1987. (Photo: Thomas Uhlemann / Bundesarchiv)

How did life at Metropoltheater change, on a practical day-to-day level, after the wall had come down?

There was a special situation in Berlin. After the fall of the wall, many people from the West who had been regulars at the Metropol before 1961 stormed back into our house. We had amazing ticket sales after the first year, in which everyone had other needs to take care of and wanted to travel all over the place, at least if they were from the East. But soon enough the exodus of East-Berlin audiences was compensated by the arrival of West-Berlin fans. Till that happened, we went through a rather rough patch: I recall performances of Frau Luna with only 15 people in our massive auditorium. That quickly changed, luckily. Yet the new Western audiences would not have come to see any DDR titles, they wanted their “good old operettas” performed in a tradition they were familiar with. And we catered to that.

Did you not try to “sell” the new Western audience your DDR shows, as a matter of pride in your own history?

No, there was no pride at all, because we had to look forward and think commercially. That happened very fast. And the new people in charge at Metropoltheater realized that they could only save our company by playing for “cash” via ticket sales. And that meant that everything we had played till then, in terms of DDR shows, had to be left behind. In the beginning no one really missed these titles, because the focus was on other things. There was so much change – so many jobs were suddenly gone, so many everyday securities vanished – that many were busy securing their existence or building a new one. The old “Heiteres Musiktheater” titles were not a priority under such circumstances.

Maria Mallé in her post-Metropoltheater career as Jente in “Anatevka” at Seefestspiele Mörbisch, 2014. (Photo: Private)

In 1995 René Kollo took over the directorship of Metropoltheater, as a “savior from the West.” How did he react to the former DDR titles?

He wasn’t interested in shows from the DDR. We had a house magazine called Metropol Journal. In the first issue under Kollo’s directorship in 1995 he stated in the preface that “We have to catch up with [lost] 50 years!” That demonstrates such a lack of respect, I find. And then came the “catching up” with his opening production of Die lustige Witwe, he sang Danilo, Karen Armstrong, the wife of Deutsche Oper intendant Götz Friedrich was Hanna Glawari, and Melanie Holiday played Valencienne. There were golden angels flying around with bow and arrow, there was a pulsating heart with lots of artificial fog for “Lippen schweigen.” It was so embarrassing that I sneaked out of the theater through a back door. We certainly produced a lot of crap in DDR times too, but never that much crap and so much loveless emptiness. There was a total lack of everything, including a basic technical command of the genre. Till that night I had assumed that being a stage director was a regular job. But Mr. Kollo proved me wrong. He thought he was able to do everything. In the end, he was “just” a tenor. Considering his great past as a singer, I am willing to accept his merits as a tenor. But he was no stage director and no theater director. What he did, in the years that followed till we closed in 1997, was grossly negligent.

The ladies of the ballet in “Messeschlager Gisela,” at the Staatsoperette Dresden 1961. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

A year later, in 1998, Neuköllner Oper presented a Peter Lund production of Messeschlager Gisela. Critics raved about the once famous DDR revue operetta…

I remember the opening night at Neuköllner Oper, which I attended together with composer Gerd Natschinski. He hoped that this production might inspire a revival of DDR operettas, as did I. But, with all due respect for Peter Lund: Neuköllner Oper doesn’t have the international appeal to kick off a wider renaissance.

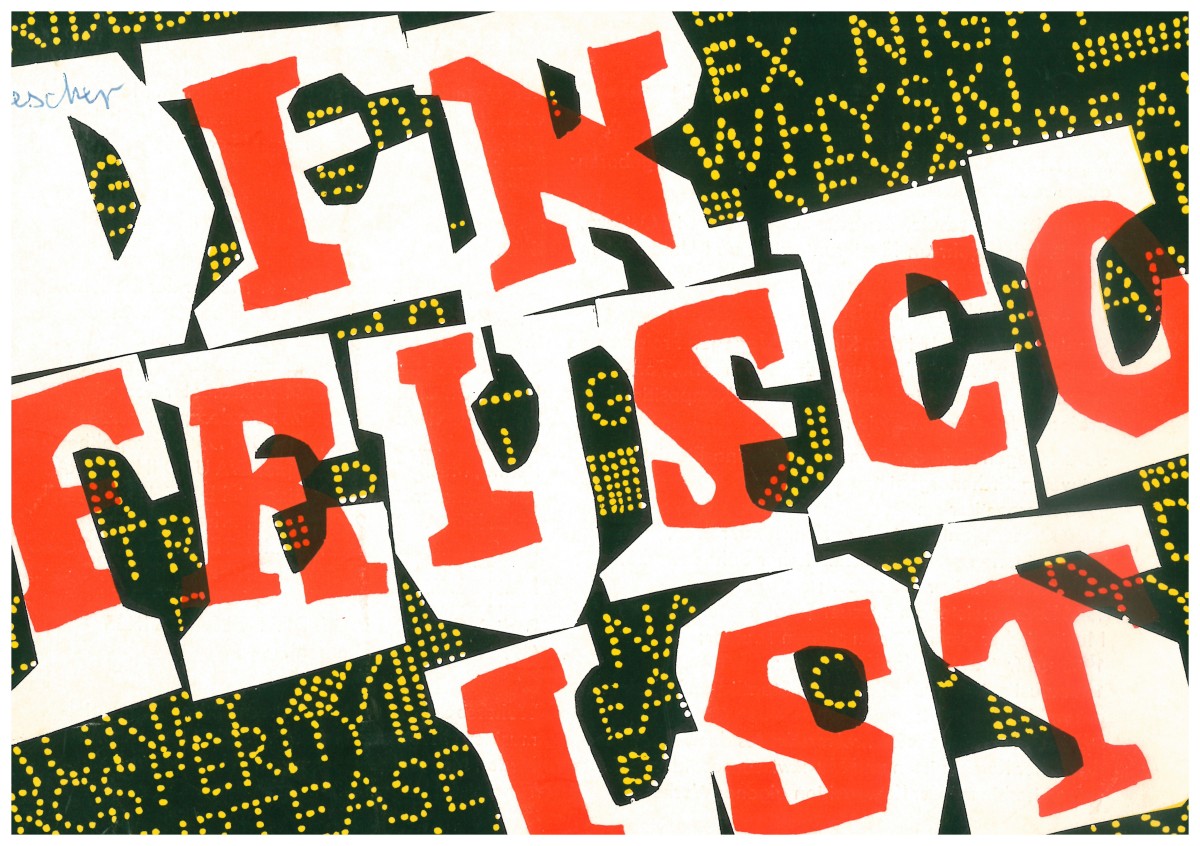

Cover of a program for “In Frisco ist der Teufel los” from 1965. (Photo: Archiv of the Operetta Research Center)

Once celebrated composers such as Gerd Natschinski (Mein Freund Bunbury) and Guido Masanetz (In Frisco ist der Teufel los) stopped giving interviews to discuss the operetta situation in the DDR and their careers.

Being confronted with this new situation – at that point in their lives – silenced many artists, having witnessed how their entire careers and everything they had worked for had been cancelled, just like that, from one day to the next. As a result, many put their heads in the sand. Because they were tired of defending themselves all the time and explaining why they made certain choices. It was actually hopeless trying to explain anything, no one wanted to hear about it. Instead, people wanted sensations and speculations. You were either “good” or “bad” with regard to your former politics. There was nothing in between. So if anyone stuck his head up he had to have an absolutely clear conscience that he never ever said anything publicly or signed something that could be used against him. Because everything was dug up and used to get rid of people. Just think of the Gregor Gysi affair and how fabricated Stasi rumors were instrumentalized to kill his political career, for years. Many who were not as eloquent as Mr. Gysi were afraid and preferred to stay out of the spotlight. They didn’t want to be put in a corner they couldn’t get out of anymore.

The symbol of East German’s party SED: the “Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands.”

You are referring to Natschinski and Masanetz having written political cantatas for the annual party meetings of the SED…?

It’s a bit like in the movie Mephisto by István Szabó: the story of an exceptional artist who collaborates with political powers because he wants to work and have a career, who doesn’t ask questions so he can fulfill his artistic dreams. Many DDR artists were worried, later, that their closeness to the political party would be turned against them. So they never gave interviews, never wrote memoires, never appeared publicly. And now they are all dead and their stories have mostly gone to their graves with them.

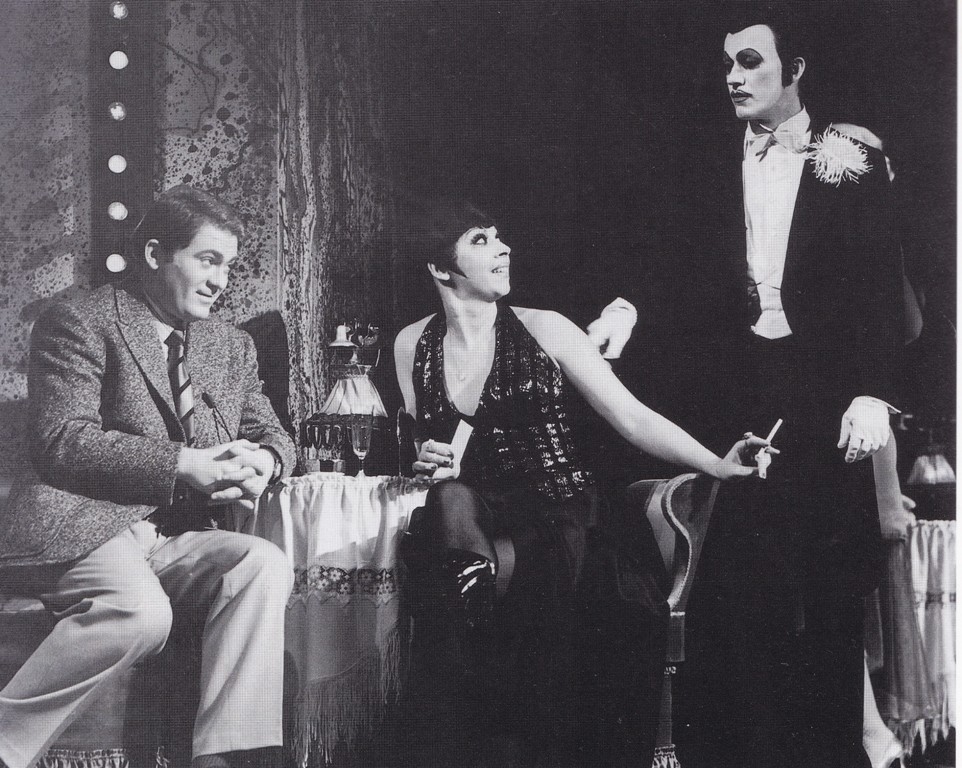

Maria Mallé as Sally Bowles in “Cabaret,” Metropoltheater 1977, together with Gunter Sanneson as the Conférencier (r.). (Photo by William Pauli from the book “…daß die Musik nicht ohne Wahrheit leben kann: Musiktheater in Berlin nach 1945″ / Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin)

In the DDR you did not just play the newly created “Heiteres Musiktheater” titles but also musicals and operettas from the West.

The broad offering of titles – be it Broadway musicals, older operettas, new musical theater works from the DDR – was singular. It was possible for audiences to see artists and complete ensembles in all their versatility. Because we performed it all, as a result of the repertoire system in East Germany with daily changing titles.

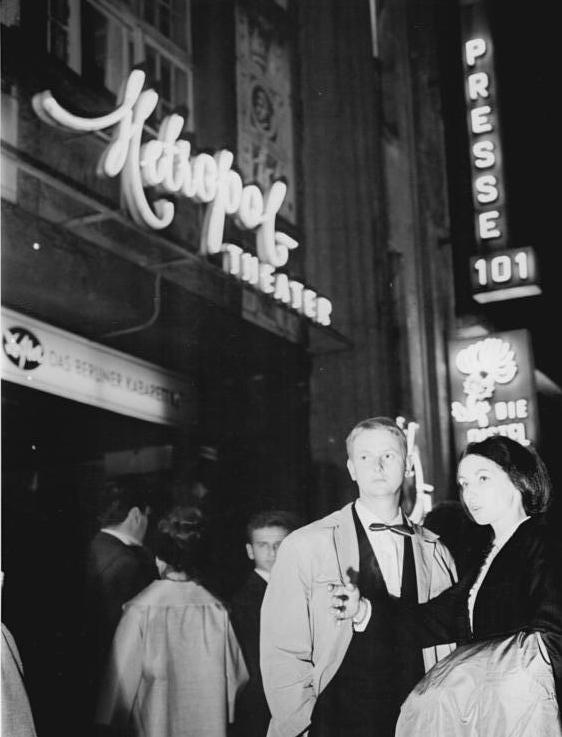

People in front of the Metropoltheater on Friedrichstraße in 1966, next to the entrance to the political cabaret Distel. (Photo: Klaus Franke / Bundesarchiv)

Did you also play shows from other Socialist and Communist countries?

There was a regular exchange between the musical theater companies in various Eastern European countries. We were all in contact with each other. Shows from Poland, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia etc. were performed in the DDR. We even had a so called “Woche des DDR Musicals” in the 1970s and 80s where colleagues from befriended foreign operetta theaters came. There was the Nova Scéna in Bratislava with who we, as Metropoltheater, were in especially close contact. They came to Berlin with guest productions, we went there to perform. Always in the original language, without subtitles. We read the synopsis beforehand, and then tried to follow the plot. The language barrier didn’t bother anyone, because we were interested to see how the others handled their material. So we could learn from them. I still have a poster from a concert in Moscow where artists from all over the Socialist and Communist world came together and presented numbers, to show one another what their state of the arts was.

Poster for “Die Frau des Jahres,” Friedrichstadtpalast 1963.

Audiences in these countries had learned to read between the lines and catch political jokes even though there was censorship and strict regulation of what was allowed to be said. Is it possible for Western audiences, today, to understand such “hidden meanings”?

We called it “Versteckte Aktualität“ back then, which didn’t work anymore after the “Wende.“ I recall that in political cabarets this was particularly problematic. The sharpened ear of DDR audiences was famous and notorious for picking up subtle provocations. But that was simply plastered over by colossal global change, suddenly other things were prioritized and the former form of avoiding censorship became obsolete.

Recently, Semperoper Dresden offered a DDR operetta concert, Musikalische Komödie in Leipzig presented a revival of Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten as an important signal for bringing “Heiteres Musiktheater der DDR” back into focus, and even Komische Oper Berlin is thinking about DDR operettas as a repertoire “Schwerpunkt.” All of these companies are in the former East of Germany…

I believe that the geographic connection with the East still exists, and it influences people. In the former DDR territory there still is an audience for whom these works were once part of their lives.

The successful series “Deutschland 83″ about the collaps of the DDR and life behind the Iron Curtain in East-Germany, with Jonas Nay and Maria Schrader in leading roles. (Photo: Amazon Prime)

A wider and international audience has become newly fascinated with DDR history via TV shows such as Deutschland 83 (and Deutschland 86 and Deutschland 89). Could that new interest affect “Heiteres Musiktheater” as well?

It’s a pity if research has to make such a detour, but if it helps – great!

Film historian and museum founder Wolfgang Theis recently said in an interview that the reappraisal of history always skips a generation.

The second generation usually has a less contaminated perspective than the generation immediately following major turning points in history, yes. So maybe that’s why so many young researchers and artists are suddenly taking a fresh look at operetta from behind the Iron Curtain. Maybe because it reflects the history of their parents and grandparents, a society they want to learn more about, a political system that has influenced their upbringing. And maybe because many of these forgotten shows are actually good, and the topics they tackle are still relevant… just think of Gerhard Kneifel’s Aphrodite und der sexische Krieg, a 1986 anti-war piece which grew out of the famous DDR “Friedensbewegung.” There is so much to rediscover and enjoy. Not just for nostalgic reasons.

Als Mitglied im Vorstand der Freunde und Förder des Deutschen Musicalarchivs e. V. und gleichzeitig langjähriger Sammler von z. B. Programmheften der DDR-Inszenierungen des Heiteren Musiktheaters, freue ich mich, dass für die so schmälich vernachlässigten Produktionen der ehem. DDR, CSSR, Polen, Ungarn und, und, und mit dieser Publikation eine Lanze gebrochen wird. Musikalisch waren sie durchaus in vielen Fällen sehr sehens- bzw. hörenswert. Ideologisch beeinflußt – fast immer! Wobei ich bei der gerade über Weihnachten gestreamten “Cinderella”-Produktion der Staatsoperette Dresden oft gedacht habe, diese Inszenierung hätte auch vor 1989 in der DDR funktioniert, mit´der neuen Deutung und erweiterten bzw. abgeänderten Handlung der 2013-Broadway-Produktion. Es wäre schön, mal die ein oder andere Produktion, die hinter dem “Eisernen Vorhang” entstanden ist, mal wieder auf der Bühne zu sehen. Oder den ein oderen Musikfilm wie “Limonaden Joe” oder “Die Dame auf dem Gleis” im Fernsehen zu sehen.