Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 May, 2017

The Staatsoperette Dresden has been – for many years – one of the few theaters in Germany, before and after re-unification, entirely devoted to operetta and popular musical theater, along with the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig (East-Germany) and the Gärtnerplatztheater Munich (West-Germany). Not to forget the former Theater des Westens in Berlin-West and the late Metropoltheater in Berlin-East. While the Staatsoperette was “exiled” to the outskirts of town for many years, to the rural distric of Leuben, it has recently moved downtown to the brand new Kraftwerk Mitte. Such a change of location ends an era that started in the early post-WW2 years. And to mark this end-of-an-era, Andreas Schwarze has written a marvelously illustrated history of popular musical theater in Dresden from 1844 until today: 200 large-size color pages at budget price. Highly suitable for anyone who doesn’t speak German and only wants to look at pictures!

Cover of the book “Metropole des Vergnügens: Musikalisches Volkstheater in Dresden von 1844 bis heute.” (Saxo-Phon Press)

Andreas Schwarze was born 1959 in Meißen, near Dresden. He studied stage direction and has worked for the Staatsoperette since 1986 as stage director, soloist, stage author, and photographer. He has managed to collect a vast number of historic images from various sources. And he uses them – lavishly – to chronicle the history of popular musical theater in Dresden, starting with the outdoor Volkstheater of Josef Ferdinand Nesmüller.

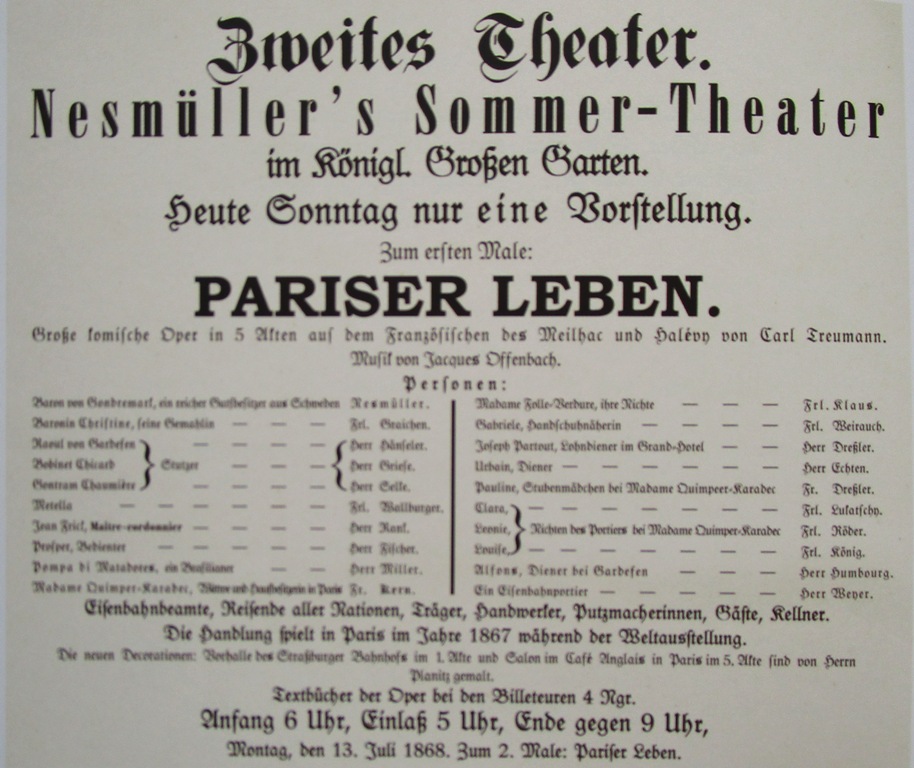

Nesmüller’s summer theater in a large royal garden of Dresden. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

It’s fascinating to see what was on at Nesmüller’s theater, e.g. Offenbach’s Pariser Leben as a “Große Komische Oper in 5 Akten,” which translates as “grand comic opera in 5 acts” with Mr. Nesmüller himself as Baron Gondremark.

Playbill for Offenbach’s “Pariser Leben” in Dresden. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

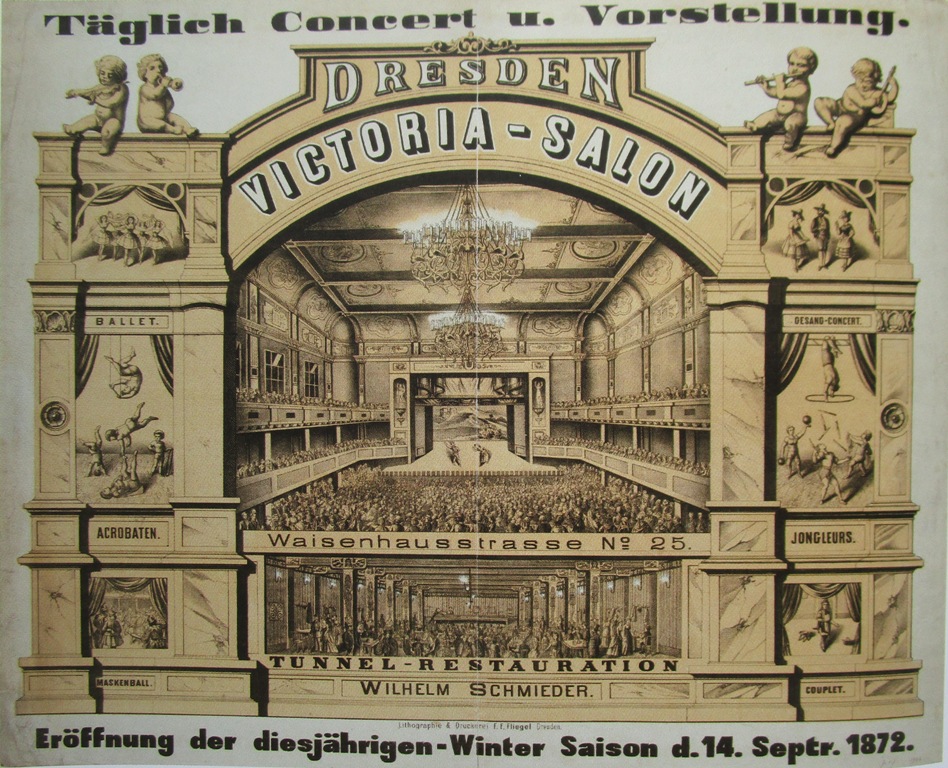

Mr. Schwarze moves on to the Herminia-Theater and its 1,110 seat auditorium. It opened in 1872, and offered famous guests from abroad, such as 22-year-old Alexander Girardi from Vienna, and Miss Finaly who was a sensation, praised as “the queen of soubrettes.” Quickly, competition established itself, like the spacious Victoria-Salon. Other stages like the Diana-Garten also get a mention.

The Victoria Salon in Dresden. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

Next comes the Residenz-Theater, run by Engelbert Karl. It showed titles like Genée’s Nanon, and kept presenting new operettas from Vienna in the years to come. Here is a photo of Carl Friese in Waldmeister, 1896.

Carl Friese in “Waldmeister”, 1896. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

A little later, the newly fashionable revues from Vienna’s biggest operetta competition Berlin came to Dresden as well, e.g. Berlin bleibt Berlin, 1910. It included a big race horse scene, seen below.

Scene from the revue “Berlin bleibt Berlin,” 1910. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

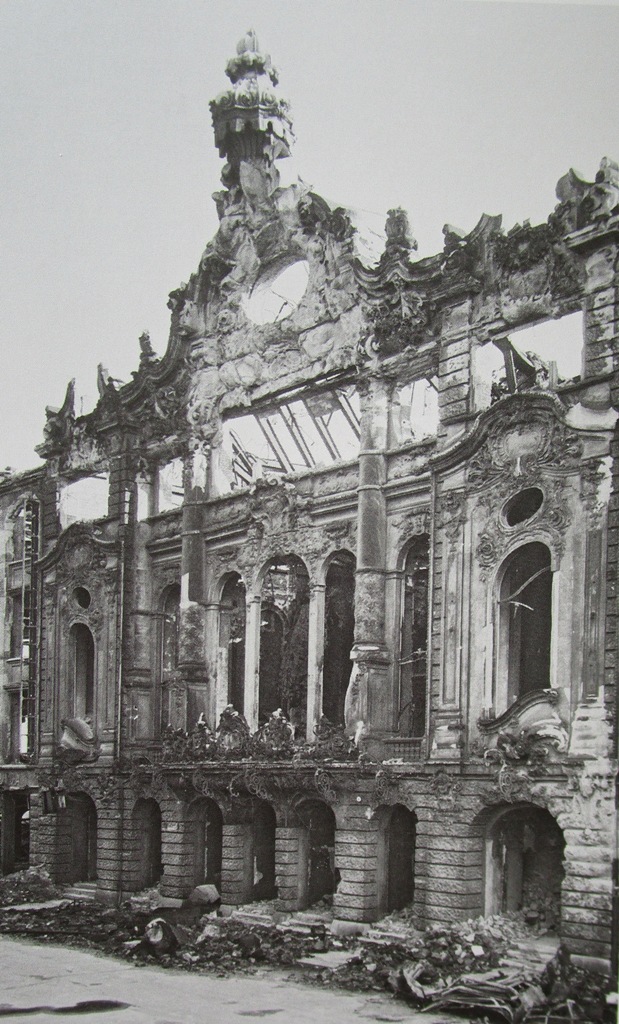

In 1906 another new theater opened in Dresden, the luxurious Central-Theater with an elegant café, restaurant and palm tree winter garden, plus a shopping mall! Lehár came and conducted there, the latest superhits were imported, among them Die Csardasfürstin with Georg Wörtge as Boni. The Central-Theater kept blossoming, even after the Nazis came to power. They presented Ball der Nationen with Curd Jürgens, but also resurrected Paul Lincke long forgotten works such as Im Reiche des Indra (1940). Like many theaters in Germany, and like many buildings in Dresden, it ended in ruins.

Facade of the Central Theater Dresden on 1 October, 1936, the night of the premiere of “Ball der Nationen.” (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

Another famous Dresden theater was the 1,250 seat Albert Theater on Albertplatz; it was later renamed “Theater des Volkes” by the Nazis, just like the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin. One could see revived “Vienna Waltz” operettas such as Die Landstreicher there in 1939 or Maske in Blau, 1938/39 or Der goldene Pierrot 1939. All approved ‘Aryan’ titles. This Theater des Volkes also ended …. as a ruin.

Scene from the 1940 production of Lincke’s “Im Reiche des Indra.” (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

Once the war was over, life and musical life started afresh. Interestingly, the former Nazi shows played alongside the newly returned former “degenerate” titles. For example, Die lustige Witwe played parallel to Kalman’s shimmy dancing Bajadere in 1946. The venues used for these performances had names such as Neues Dresdner Revue- und Varieté-Theater or Maxo-Parlo-Theater.

The ruins of the Central Theater in Dresden in 1946. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

What would later become the Staatsoperette in Plauen started as “Volksoper Plauen,” a former restaurant on the outskirts of town, near the river Elbe. It changed names of few times (Apollo Theater was one of them) and also played titles from the Nazi era, like Die Perle des Tokay, alongside the syncopated Blume von Hawaii in 1947/48. A year later, Abraham’s Ball im Savoy was played parallel to Land des Lächelns.

Scene from Kalman’s “Bajadere” in 1946. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

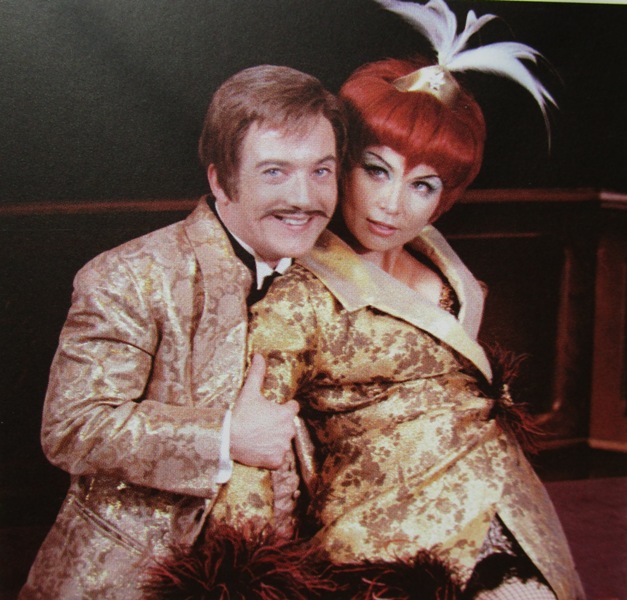

As you look at the photos from productions of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, you see everything that went wrong with the genre in these decades. And that does not only apply to genuinely East-German operettas like Mein Freund Bunbury, played at the Staatsoperette Dresden in 1965 and 1971, or Natschinski’s Messeschlager Gisela. All of these productions are documented with photographs, including Cabaret 1976, Man of la Mancha 1974, Evita 1987 etc. You might want to take a deep breath before looking at the following selection of images.

Scene from “Mein Freund Bunbury,” 1971, with Jürgen Muck as Algeron and Maria Rolle as Cecily. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

The chorus of the Staatsoperette Dresden in “Die Fledermaus,” 1990. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

The apparently never-ending era of director Wolfgang Schaller is (thankfully) not a particular focus of the book, it is not even blown up to any major importance. It’s simply there with many color photos, for example of the resurrected Cagliostro in Wien, 2015.

Before the book closes, you get more color photos of various operettas, but also many musicals like Pardon My English (2009), Hello Dolly (2010), Passion (2011), The Rocky Horror Show (2012), Der Zauberer von Oz (2013) and Catch Me If You Can (2015). There are last glimpses of the abandoned Leuben venue, and a few computer generated images of the new Kraftwerk Mitte.

Opening scene of the film festival, where “Highway to Beauty” premieres. (Photo: Staatsoperette Dresden)

It’s a gloriously illustrated theater history of Dresden, a city not too well-known for its popular musical theater relevance, as compared to its importance in opera history (Weber, Wagner, Strauss). Browsing through these pages made me realize, page by page, how much tradition has been lost after WW2. And how rapid the downward spiral was after 1933. Andreas Schwarze does not gloss over any of this, though he’s not particularly critical of the last few decades either.

The luxurious café inside the Central Theater, Dresden. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

I wish there could be more such illustrated histories of theater scenes beyond Broadway, London’s West End, Paris, Vienna, Berlin or Budapest. The book reminds up what a rich theater scene thrived outside the established centers and how intense the dialogue between the centers and the “provinces” was, with stars going on tour and hit shows being re-produced almost immediately after their world-premiere.

The ladies of the ballet in “Messeschlager Gisela,” at the Staatsoperette Dresden 1961. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

Looking at the late stages of operetta history in Dresden also reminds us why one should definitely not leave the genre entirely in the hands of the Staatsoperette and its omnipresent director Mr. Schaller. What was produced in Dresden after 1945, and 1989, is not seriously representative of the genre in its original glory. That, too, is something that becomes clear in this book and from the many historic reviews quoted throughout.

Splendid illustrations and interesting subject. Now do one about Berlin. Schneidereit is rather elderly… K

The Schneidereit book is actually the best there is…. and it would be great to update his text and publish it in combination with historical photos as a comparable coffee table format book. Maybe in combination with the Stadtmuseum Berlin, where many of the images can be found?