Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 August, 2014

It might come as a bit of a surprise to operetta fans of today to find a so-called “Viennese Operetta”, premiered in Vienna and written by some of the top Viennese specialists in the field, set in Hollywood, of all places, and dealing with an eccentric film diva, ruthless paparazzi, studio bosses with lots of cash but limited brain capacity, hyperventilating film directors and the like.

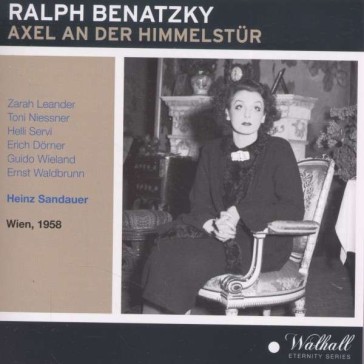

A complete recording of “Axel” with Zarah Leander, made for ORF in 1958.

It’s an operetta that also contains only one real Viennese Waltz song which celebrates, in turn, the glories of US-films set in Austria, Mickey Mouse in Lederhosen and American tourists who fall for dirndl fashion while visiting Salzburg. The rest of the score contains a languorous blues (“Gebundene Hände“), a slow waltz, a tango (“Gute Nacht“), foxtrots, and some totally mad cap yodel-numbers (“In Holly-Holly-Hollywood“). The piece I am talking about is Ralph Benatzky’s 1936 megahit Axel an der Himmelstür which he wrote with cabaret stars Paul Morgan, Adolf Schütz (book) and Hans Weigel (lyrics), and which was premiered at the Theater an der Wien with a superlative cast headed by Max Hansen as the Hollywood reporter, Axel Swift, and newcomer Zarah Leander in the role of the film diva Gloria Mills. Miss Leander caused such a sensation in the show that, shortly afterwards, she became a real life film diva.

The German film company Ufa hired her and turned her into one of the brightest stars of Nazi-cinema, in the place of Marlene Dietrich who had turned her back on the Third Reich.

It was actually not unusual for Viennese operettas of the 1930s to be set in Hollywood or in America in general. Operettas in those days were still a commercial art form, and authors always chose topics and settings that were up-to-date and of general popular interest. Carl Millöcker’s Der arme Jonathan of 1890 had already used America as its setting, as had Leo Ascher’s Vergelt’s Gott in 1905 and Leo Fall’s Dollarprinzessin in 1907.

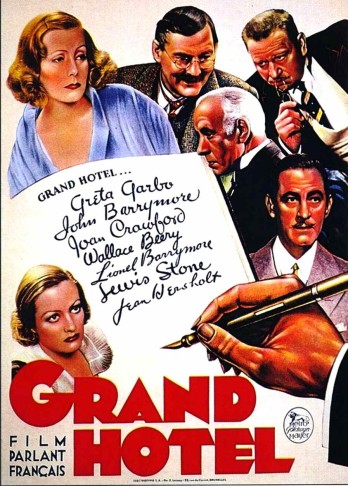

Poster for the film “Grand Hotel” which inspired “Axel an der Himmelstür.”

All three shows had premiered, like Axel, at the Theater an der Wien. But what could have been more up-to-date by the 1930s than Hollywood? Film stars were just as unapproachably the subject of everyman’s and everywoman’s daydreams by then as they have been ever since. No wonder, that quite a few famous operetta composers wrote shows which dealt especially with the film world and with what went on behind-the-camera where the public would oh-so-have loved to peep – from Oscar Straus’ Hochzeit in Hollywood, Emmerich Kálmán’s Herzogin von Chicago, both premiered in 1928, to Paul Ábrahám’s Märchen im Grand Hotel of 1934. Yet the most dazzling Hollywood-operetta of them all, and indeed also the most successful, critically and commercially, was and is Benatzky’s Axel, a work which offers an ideal blend of all that represents the very best about German-language operetta before the Nazis turned it into the boring nostalgic ‘fluff’ we know it as today. In contrast, Axel is sharp, witty, and politically extremely topical. Alongside its main plot, which concerns the film diva Gloria (strongly modeled on Greta Garbo in the film Grand Hotel) and the reporter Axel, the operetta also shows Viennese exiles working in Hollywood.

The creative team of “Axel” in 1935, with Hollywood star Adolphe Menjou visiting (front row, second from right). He is “recycled” in Max Hansen’s “Holly-holly-hollywood” number.

Given the political circumstances in Germany after 1933 it was a rather realistic subplot. What is special about Axel is that the authors – some of whom, like Benatzky, emigrated to the US themselves after the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, or, like Paul Morgan, were deported and killed in concentration camps – deal with the exile topic in a light hearted and self-parodic way, with an esprit that is wholly typical for ‘Jewish Operetta’ before 1933/38. It is hard to imagine anything more funny than the ‘All-Jewish’ ensemble of the film crew – an ensemble which was headed by Paul Morgan himself on stage as Cecil McScott, the “chief producer” – arguing over how to handle the eccentric diva.

Originally, the role of Gloria was intended for Liane Haid, a German film star and operetta actress who had appeared in the silent movie version of Im weißen Rössl 1926, and later in various other Benatzky shows and films. When the charming but hardly eccentric Haid pulled out of the project at the last moment, the production team needed an urgent substitute. The Danish actor Max Hansen, Benatzky’s original Leopold in Im weißen Rössl and by 1936 a superstar on stage and screen, recommended an unknown singer from Sweden whom he had heard on one of his Scandinavian tours. The authors invited Zarah Leander to Vienna and auditioned her. Benatzky wrote in his diary: “Zarah Leander is a great, red-blonde, heroic contralto from Stockholm, she has what one might call a ‘Junoesque appearance.’” She was definitely a different prospect to Liane Haid, and though casting Leander meant that Benatzky had to re-write most of the score and transpose it severely down, Leander, with her stunning looks and vibrant basso profundo-voice, was an overnight sensation. Max Hansen described the opening night: “Zarah sang with a voice that reached the last corner of the auditorium. I stood in the wings and watched the audience. People sat up and listened when she came on. What was this? A prima donna who wasn’t a soprano, not even a mezzo? The first minutes went by with cautious waiting, but after a while people began to whisper among themselves, to nod and to exchange knowing looks.

Soon Zarah had conquered her audience – people realized that she was something unusual and precious.

That she was a real artist up there on the stage.” The Neue Freie Presse appropriately labeled Leander the “Greta Garbo of operetta” and after the 100th successive performances, a Viennese caricaturist rhymed: “Geschundene Hände, Beifall ohne Ende – Das ist der Clou der Saison! Schon 100 beinander! Zarah Leander spiel’n seh’n ist eine Passion!” (“Poor hands, applause without end. She is the highlight of the season. Already 100 performances. To see Zarah Leander perform is fulfillment.”)

When Leander went onto her real-life film career, she insisted on Benatzky as the composer of her songs, and he would write two of her greatest hits for her in her first film Zu neuen Ufern (1937): „Ich steh’ im Regen“ and „Yes, Sir!“

Meanwhile, Axel was performed in Germany in an adapted Nazi-version that eliminated the names of the Jewish authors. It was played at the Gärtnerplatztheater Munich, among other places, with Johannes Heesters as the reporter, who now no longer worked in Hollywood but for a German newspaper in Germany, and who was writing about German stars in German films for German audiences. There were even plans to turn the show into a film with Zarah Leander herself in the lead role, but by 1943 she had retreated to Sweden and the film Liebespremiere was instead made with Kirsten Heiberg as ‘the diva’. Franz Grothe wrote a completely new score and the film had very little resemblance to the original stage show.

After the war was over, Austrians and German producers were not particularly interested in promoting operetta as an international art form à la Hochzeit in Hollywood or Märchen im Grand Hotel. Instead of shows with flamboyant Hollywood or other of-the-moment topics they rather played old-fashioned Viennesey pieces that did not touch upon anything remotely connected with National Socialism, “Entartete Musik”, exile or other such unwelcome things. Viennese operetta of the years after 1945 was nostalgic, schmaltzy, full of waltzes, violins and champagne. There was no room for a jazzy piece like Axel an der Himmelstür, not even in its toned down ‘Aryan’ Gärtnerplatztheater version.

However, since Zarah Leander was still a superstar and adored diva in post-war Europe, and since she still regularly performed songs from “Axel” in her concert programs, the show was not entirely forgotten.

Thus it was that in 1958 the Austrian radio station ORF decided to record the full piece with Zarah Leander herself. Back in July 1936, only Max Hansen – the then star of the show – had recorded his numbers prior to opening night, after the success of Leander she made one recording in September 1936 (“Eine Frau von heut’“). And only a year later, while already under contract for Ufa, did she record “Kinostar” with the Ufa orchestra. 22 years later, Vienna went into a wild flutter when Miss Leander arrived in the city for the recording sessions, and on the Austrian radio in 1958 audiences nationwide had the first chance to hear a Leander recording of the entire score.

Zarah Leander recording “Axel” in 1958.

On this recording, Leander is simply sensational as Gloria, probably even better than she had been in 1936, partly because by this time she herself was just as mad and grand as the story and the character of Gloria Mills demand – satirical operetta had turned into bitter reality! One has only to listen to Leander melodramatically blasting out “Ihr habt ja aus mir eine Puppe gemacht” (‘You’ve turned me into a puppet!’) to know how unique the Zarah Leander of 1958 was.

What also makes this recording special, and is the second glory of this ORF-version, is that here we have one of those rare times where a new set of orchestral arrangements, made by Heinz Sandauer, turn out to be actually as good, if not better, than the original ones. Instead of the ‘sweet’ and ‘lush’ operetta orchestrations typical of the ‘fifties, he has gone for a splashier, more Ufa-kind of style, which jumps right out at the listener.

These great pluses can help one forget that Toni Niessner, as Axel, though suave in his own right, is no match for the zany Max Hansen. However Niessner tries his best with the “Holly-Holly-Hollywood”-yodel, and the re-vamped waltz finale about the “Vienna Film” (now a duet) is superbly executed by Helli Servi as Jessie Leyland and Erich Dörner as Theodor Herlinger, the Viennese exile in Hollywood. The two of them also give a rousing rendition of the “Taboo Foxtrot”. Strangely, the entire opening sequence in Cecil McScott’s Hollywood office is not sung but spoken in rhyme (without music). And the role of Dinah (a sort of black-face “Mammy” in the Gone with the Wind -tradition) is limited to some rather un-amusing side remarks. But who cares? Zarah Leander dominates everything and steals the show from everyone. She is indeed: “The Star.”

Zaral Leander together mit Max Hansen, in the original production of “Axel.”

Considering the rewarding central role of Gloria, the hit song “Gebundene Hände” and the still wonderfully up-to-date Hollywood-story, and considering how many Zarah Leander impersonators tour Europe with her repertoire today, it is surprising that hardly anyone has performed Axel an der Himmelstür since. It would be an ideal vehicle for (drag) divas or countertenors like Tim Fischer, Ursli Pfister, Jochen Kowalski, Daniela Ziegler, Dagmar Manzel or even Desirée Nick (not to mention Sunset Boulevard-leading ladies such as Glenn Close, Patti LuPone or Elaine Page.) Perhaps this first ever CD-release of the entire show will remind theatre directors and singers of Axel and its potential.

;