Emese Lengyel / Széchenyi István University (Győr, Hungary)

Operetta Research Center

19 January, 2025

József Hűvös Botfai (1848-1914), originally from Nagykanizsa, moved to Budapest, where he became a respected lawyer, an adviser to the Hungarian royal court, as well as an expert on transportation. His family received a noble title in 1897 (along with the Botfai surname), with which the Hungarian government recognized the merits of József Hűvös. He and his wife, Mária Heller (1848-1918), raised seven children, three of whom chose artistic careers: Kornél Hűvös Botfai (1875-1905) became a writer, Iván (1877-1954) a composer, and László (1883-1972) a sculptor.

Composer Iván Hűvös. (Photo: Magyar Zeneiskola/Arcanum, 1912)

The family originally bore the surname Hirschel, which was changed to Hűvös in 1882. Iván’s life, in addition to composing – as he is the author of many songs and operetta music – was filled with political, public and journalistic activities. The present article focuses on the life of the composer and the performances of his stage works, and it is built upon the publications of the then-contemporary press. [1]

In 1928, i.e. about fourteen years after his father’s death, Iván Hűvös wrote at length about his late father’s merits in the Pesti Hírlap, titled, “What was my father like?” In the article, he notes that “[t]his teary-eyed, boyish recollection is perhaps not suitable for listing all the works that are associated with my father’s name. With this article, I merely aim to point out the great work of his life, that is, the creation of the electric tramway, with which he preceded many European metropolises. Together with Balázs Mór Verőczei, who died young, he developed the plans for the tramway, as he recognized with a keen eye the immeasurable importance of tramway transport and, with the smile of doubt, defying a thousand difficulties and seemingly insurmountable obstacles, founded the Budapest City Tramway. There are still many people who remember that notable day in 1885, when the very first small tram glided along the boulevard, almost like a ghost, from Nyugati Railway Station to Király Street, and how happy and proud my dear father was when we, his small children at the time, could get on this little tram.” [2]

Following his father’s footsteps, Hűvös worked as the general manager of the Budapesti Városi Villamos (Budapest City Tramway Company), and father and son became colleagues. Hűvös remembers these years, claiming that “[he] worked by his [father’s] side for more than two decades in managing the affairs of Józsefváros and the tramway, which was the closest thing to [his father], while [his father] remained the same family man and person for him.” Hűvös remembers his mother in connection with a family tragedy: one of his younger brothers died in an accident – “he was cut in four by the horse railway on Kerepesi Road” [3] – which his mother could not process, thus, they scarcely allowed guests in their home and lived apart from one another. Music was – as in most bourgeois families – a part of their everyday life: “[...his] happy parents were extremely fond of music, [his] mother had a particularly excellent ear for music, and even if she felt better on some days, if [they] spoke to her, she would answer [them] in poems. On evenings rich in such sentiments, one of [them] sat down by the piano, which brought indescribable joy to [their] good parents.” [4]

He met his first wife, Piroska Jellinek, through his connections with the railway company (the family were interested in the “yellow tram” company). The lady was none other than the daughter of railway mogul Lajos Jellinek, a relative of Henrik Jellinek, the general manager of the Budapest Helyiérdekű Vasút (Budapest Railway of Local Interest), in short, BHÉV, i.e. HÉV. At the same time, the alliance signed in March 1907 [5] proved far from lasting, as the young couple divorced a year later. Tying the knot for the second time, in 1915, Hűvös led Ilona Sándor-Csíkszentmihályi [6] to the altar, whom he was married to for several decades. Later and ultimately, Hűvös married Magdolna Csatári in 1947.

“Inheriting wealth is fortunate, inheriting talent is both fortunate and a bliss” [7]

Besides his role in transportation, Iván Hűvös also occupied a position in the musical scene, as he joined the Magyar Zeneiskola (Budapest Hungarian Music School) in the 1911/1912 school year. [8] Details about his relationship with music and his musical training are noted in the following school bulletin: he started taking piano lessons as an elementary school student, then he strove to improve as a high school student. “[...] he devoted all his free time to music and studied music theory and composition with great enthusiasm.” [9]

His career – both in public and in the musical scene – was strongly influenced by his family’s involvement in politics and public life: his formal and informal connections and opportunities (studying abroad, occupying a senior management position with his father, membership in numerous charitable and cultural institutions, etc.) determined him to pursue a similar career from a young age.

His work as a composer was limited to songs, operettas, folk plays, and ballet music. His very first operetta was staged in March 1902 at the Népszínház (Pest People’s Theatre). [10] It is noteworthy that this was the year when composer Jenő Huszka’s second stage work, Bob Herceg (Prince Bob, December 20, 1902, People’s Theater) [11] premiered; and a year later, the Király Színház (King’s Theater) opened its doors, while two years later, Pongrác Kacsóh’s János vitéz [12] (John the Valiant, November 18, 1904, Király Színház) premiered as a huge success.

Was he a dilettante or a “good enough” author?

Iván Hűvös’ first operetta was titled Az új földesúr (The New Landlord), and its libretto was written by Henrik Incze (1871–1913) [13].

Librettist Henrik Incze, 1913. (Photo: Unknown / Színházi Élet)

Even though several Hűvös compositions can be found in the Music Library of the Országos Széchenyi Könyvtár (National Széchenyi Library), one has to rely exclusively on press sources for characterizing the work in question. In the March 23, 1923 editions of the Budapesti Hírlap and the Magyar Nemzet, a completely different assessment was published. It is well known that if someone excels in two vastly different professions (which is not so rare), it can certainly be objectionable to many. For some, he is not “this” enough, for others, he is not “that” enough, and all that can be found in the contemporary “criticism”.

Moreover, this type of “disapproving” press publicity is by no means a modern invention, so it is worth reading reviews of Hűvös’ works with this in mind. Besides, as Iván Hűvös worked as a journalist, he was a confidant as well as a good friend of many newspaper moguls or editors. Despite its irrelevance in the case of his stage works discussed, it is also evident that from 1933, Hűvös also worked as the chairman of the editorial board of the Ország-Világ weekly newspaper. As for the different tone of the two articles, it is assumed that theatrical and individual interests were behind the opposing judgements. Because the two reviewers truly made a judgment.

A Budapesti Hírlap employee called Hűvös, but also Incze, dilettante authors, claiming that “[t]he music of this novelty has some numbers that even a professional composer would not be ashamed of. The music shows a lot of natural feeling for musical beauties, and there is melody and invention, even though it is clearly the work of a dilettante. However, he is undoubtedly a talented dilettante who would have deserved better lyrics. The piece itself is weak and rudimentary. Its author, it seems, learned from those English plays with stories that are pure nonsense. Topsy-turvy confusion, impossible misunderstandings and unthinkable complications, following English examples, this is the content of the new play. We are not even tempted to tell its story, it is simply impossible [...].” [14]

Moreover, criticism directly pitied the stars who played in the piece (for example, Aranka Hegyi): “[i]t is a barren task to play in such a piece, and every single actor, both minor and major, had to know this.” [15] In comparison, it was highlighted in the columns of the former Magyar Nemzet that it is to be recommended if a theater stages a (contemporary) Hungarian play. Praising the originality of the piece, it is noted that “[...] Henrik Incze, whose libretto for Az új földesúr is, as far as I know, his first attempt written for the stage, does not ‘learn to fly on the wings tried by others’. He does not follow anyone, nor does he imitate anyone, but he writes the text according to his own ideas, not caring if it sometimes is a tad boring, due to the fact that he does not use those admissible ‘borrowings’. Incze Henrik is one of the most honest domestic authors who have ever attempted to be tested onstage, and he will be all the more valuable if he honestly passes the test. Iván Hűvös, the composer, does not follow well-trodden paths either. He also wants to produce something original, and for the most part, he succeeds. His music rises above dilettantism, and even has a surprising quality in some details. In every performance, he offers a small surprise to the audience and listening to some of his songs and his ensemble, we almost forget that he is serving us the first work of a young man. In the finale, as it is the case for all members of the youngest generation, Iván Hűvös is also quite effective, and sparkles with thoughtfulness. Thus, Iván Hűvös has left nothing behind, already with his first work, for young and non-professional Hungarian operetta composers.” [16]

However, was Hűvös inspired by other works as an operetta composer? Well, from those stage solutions of the French, Viennese and English operetta composers, surely. “Who would not excuse a young person, if, through his three big acts, in some places, already known melodies would appear?” asks the journalist, and as history has proven, great success can be achieved even without so-called “original” melodies.

Still, the play (and the performance itself) was still considered a success by the Népszínház management, since, in May 1902 the audience could already see another Hűvös work. [17] This time, he became more familiar with the genre and types of Hungarian folk plays, [18] popular from the 1840s. At that time, authors were encouraged to write new works through prize-winning folk play competitions, to which István Géczy (1860–1936) [19] also applied. It was called the Kálmán Porzsolt folk play competition. [20] The Népszínház saw the play that came in second for stage presentation, the music of which was written by Iván Hűvös. [21] Among the songs, “[...] there are several for which he well deserved the applause, with which he was also invited to stand in front of the stage lights,” [22] noted a Budapesti Napló staff member. Although the folk play, like operetta, is often a “deplored” genre, it had a star known to this day, Lujza Blaha, without whom the Géczy-Hűvös folk play would hardly have been a roaring success.

Iván Hűvös in 1935. (Photo: Unknown / Ország-Világ)

Hűvös’ partner in his next operetta “attempt” was Jenő Faragó (1872–1940) [23]. In January 1904, the Népszínház presented their work, titled Katinka grófnő (Countess Katinka). [24] At that time, Faragó was already a recognized author, the permanent author of several newspapers, and among others, head of the theater section of Magyar Hírlap, the responsible editor of the Szikra and the Magyar Figaró. In this respect, the audience, once again, placed their trust in the play. According to an article published in the Ország-Világ, Hűvös has developed as a composer over the years. “However, with the score of Katinka grófnő, Iván Hűvös has both grown and joined the ranks of our most distinguished composers at the same time. There are many ideas, melodies, musical knowledge and ingenuity in this operetta that Hűvös can truly be proud of his score; and Jenő Faragó, the librettist, can also be satisfied with his work.” [25]

Librettist Jenő Faragó, 1904. (Photo: Unknown / Ország-Világ)

The critic of Hazánk, however, analysed the piece with a much sharper pen, remarking that “Iván Hűvös composed music for the text, which does not reach the artistic level of the libretto. As dilettante music, we could say it is generally acceptable, yet it does not satisfy the criteria of music history. Iván Hűvös has little invention and sometimes goes after foreign ideas without self-evaluation. The mass scenes orchestrated in a somewhat monotonous but effective manner had their effect, as did some songs, which Klára Küry and Emma Komlóssy brought to the fore with their artistic and singing skills.” [26]

As a stage composer who can hardly be called experienced, Hűvös composed another operetta music, this time, to the text of Imre Földes (1881–1958). [27] Földes was the confidant of the Hűvös family, as it was pointed out by Endre Sós who also regarded Hűvös as a “dilettante yet not at all clumsy” composer in connection with the Földes career profile [28] published in the Jelenkor magazine. “The nationally renowned general secretary of the yellow tramway wrote several good operetta texts for the composer Iván Hűvös Botfai, a dilettante who longs for laurels and is not ‘clumsy’. This was [Földes’s] main task; but at the same time, he proved to be a good official. He came forward relatively quickly. He soon became deputy director and then director. He gained a lot of experience both in distributing free tramway tickets and in creating operetta librettos [...].” [29]

This is how the text of A két Hippolit (The Two Hippolits) was born, and the piece premiered at the Népszínház in January 1905. [30] Hűvös was referred to as the “most zealous” practitioner of Hungarian operetta, and he received a rather detailed and positive analysis in the Pesti Hírlap: “[Iván Hűvös’] ideas are mostly original, he has invention, his music is melodic and often affects the listener with the power of immediacy. There is hardly one or two parts in the entire operetta that are forced or contrived; for the most part, his melodies develop smoothly and easily, one or another of which can claim rapid popularity. Sometimes, they are trivial and banal, but this is rather due to the author’s young age. He is a mistake that is getting better every day. If his beautiful talent is fully appreciated, his self-criticism is to grow stronger and stricter, and then he will avoid such cheap effects, which, in some of his marches or polkas really put the listener with more delicate needs out of the mood. It is due to the fact that he very conspicuously reveals his ‘authorship’ with these minute details that might win the easy approval of higher circles.” According to them, Hűvös does not strive for “local flavours” in his music (which was a problem with his other operettas and folk plays as well), thus, he could even have included his works in the ranks of foreign operetta music. However, the quality of his pieces could by no means compete with that of foreign works. [31]

However, the bad press critics did not deter Hűvös from trying his hand at a new genre. In 1908, his ballet Csodaváza (The Wonderful Vase) [32], and in 1911, Havasi gyopár (Edelweiss) [33] were presented by the country’s first song theater, the Hungarian Royal Opera House. [34] The co-author of Csodaváza was Miklós Guerra (1865–1942) [35], and it seemed that Hűvös had developed so much that he convinced even the music-savvy public of his talent. A journalist of the Hét [36] wrote about his “refined operetta music” and a more substantial and classy sound that characterized his work, and this time, the papers in general did not dispute Hűvös’ artistic power. [37]

This was already a “real” success for the tramway director-composer, whose ballet music was published in a tasteful exhibition at the Pesti Könyvnyomda Reszvénytársaság (Pest Book Printing Corporation) music press. [38] During his ten-year career as a composer, Hűvös was once even able to experience success abroad, when the Csodaváza was presented at the Milan Scala under the title Siama/Siáma. [39] The Guerra-Hűvös co-authors also worked together again, and their piece was also staged at the Opera. [40] This work was an endearing fairy tale set in a small Norwegian village at the foot of the snowy mountains, and the music (composed by the praised Hűvös) was “fresh, pulsating” that resonated beautifully with the theme. But the story written by Guerra, and at the same time, his choreography was less successful. [41]

It seems that contemporary critics unfairly singled out other activities of the composer when criticizing the Hűvös works. At the same time, time itself (as we know it) obscures once bright successes. Iván Hűvös contributed to the operetta literature in the early stages of the development of Hungarian operetta, but his name no longer sounds familiar for the realms of music literature, despite the fact that his plays were presented on the capital’s stages with the biggest stars of the era, such as Lujza Blaha or Klára Küry.

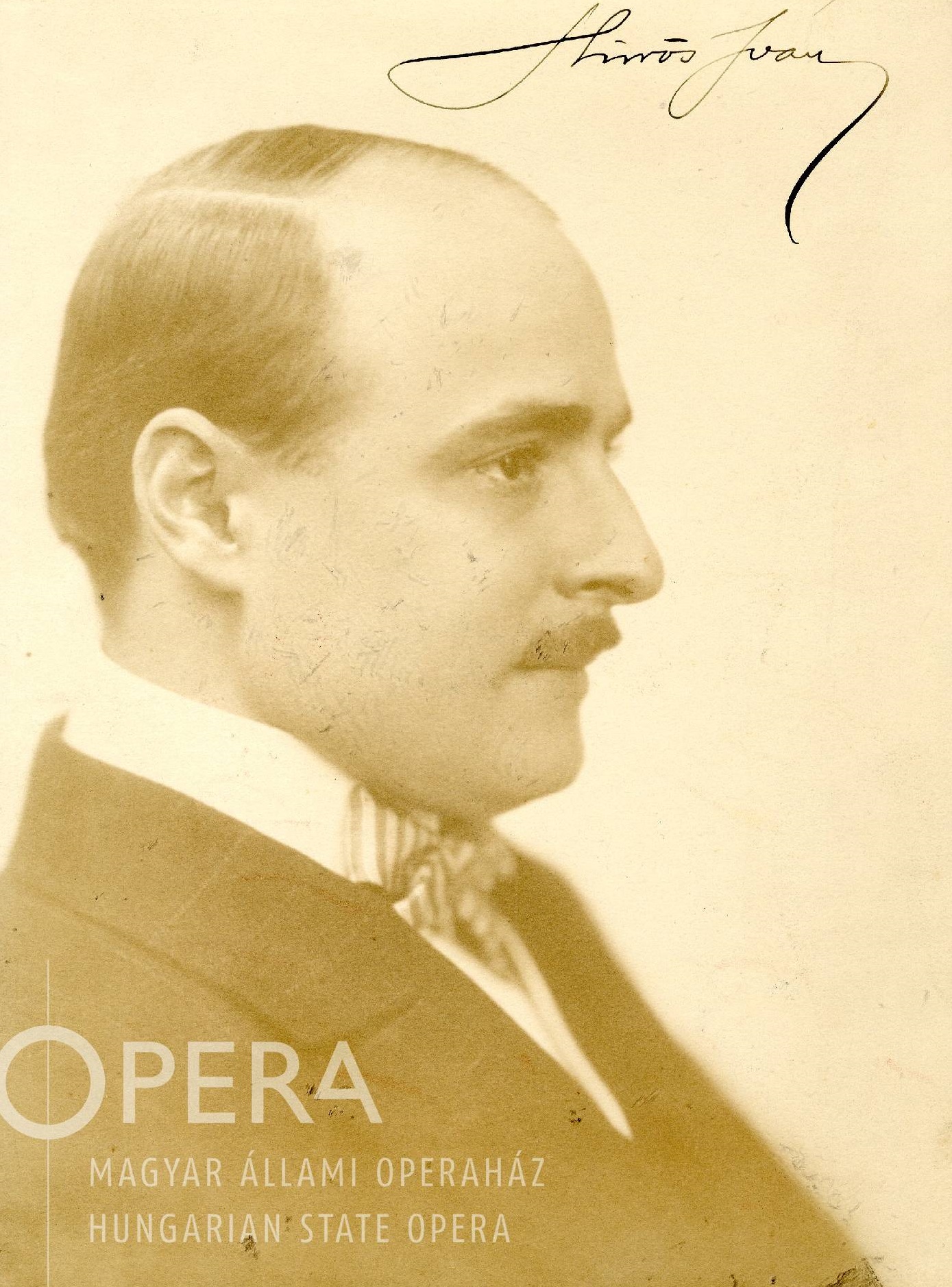

Iván Hűvös in a portrait shown by the Hungarian State Opera. (Photo: Hungarian State Opera)

[1] The Hungarian version of the article was published in the quarterly music magazine Gramofon, in the series of articles in which Emese Lengyel (assistant research fellow, Széchenyi István University, Hungary) presents the careers of famous operetta composers.

[2] Hűvös, Iván. “What was my father like?” Pesti Hírlap, vol. L, no. 6, 8 Jan. 1928, pp. 37–38.

[3] Ibid., p. 37.

[4] Ibid., p. 38.

[5] “[...]the fully illuminated church, adorned with beautiful palm trees and rugs, was filled to capacity with an elegant audience. The new couple was blessed by Dr. Samuel Kohn, the chief rabbi, and the singing parts were performed by Chief Cantor Lazarus,” reported the contemporary press about the wedding. n.a. “Házasságok.” Egyenlőség, vol. XXVI, no. 12-13, 24 Mar. 1907, p. 10.; n.a. “Házasság.” Ország–Világ, vol. XXVIII, no. 12, 24 Mar. 1907, p. 236.

[6] “Iván Botfai Hűvös, the general manager of the Budapest City Tramway Company, married Ilona Sándor Csíkszentmihályi today. The witnesses were János Sándor Csíkszentmihályi, home secretary, and Imre Jakabffy, Privy Counsellor and Member of Parliament.” n.a. “Házasság.” Magyarország, vol. XXII, no. 298, 26 Oct. 1915, p. 10.

[7] n.d. “Iván Botfai Hűvös, President of the Hungarian Music School.” In: Lajos Schnöller, editor. A Magyar Zeneiskola értesítője az 1912–1913. tanévről. Budapest, Márkus Samu Könyvnyomdája, 1913, p. 3.

[8] “The Hungarian Music School celebrated its 26th year of existence during the past school year. Few events in the history of our institution are as delightful as the one we can now boast of. On May 25 of this year, the Budapest Hungarian Music Association, our governing body, held an extraordinary general meeting, during which they elected István Bárczy, the Mayor, as honorary president – as he resigned from the presidential position due to his heavy commitments – and chose composer Iván Botfai Hűvös as president. In this way, we succeeded in gaining two men for our noble cause whose names are already a program in themselves. Their election undoubtedly represents progress, development, and success for our institution. They possess both musical expertise and the knowledge and youthful energy that meet the standards of today’s world.” n.d. “A Magyar Zeneiskola működéséről az 1911–1912. tanévben.” In: Lajos Schnöller, editor. A Magyar Zeneiskola értesítője az 1911–1912. tanévről. Budapest, Márkus Samu Könyvnyomdája, 1912, pp. 3–7.

[9] n.d. “Iván Botfai Hűvös…” p. 3.

[10]Berczeli Károlyné, editor. A Népszínház műsora (Adattár). Budapest, Színháztudományi és Filmtudományi Intézet – Országos Színháztörténeti Múzeum, 1957, p. 47.

[11]Berczeli Károlyné, editor. A Népszínház műsora… Ibid., p. 48.

[12] See further: Lengyel, Emese. „A János vitézen túl: Kacsóh Pongrác élete a természettudományok és a zeneművészet metszetén.” Gramofon, vol. XXVIII, no. 3 (145), 12–15, pp. 12–15.

[13] Székely, György, editor-in-chief. Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon. Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1994, p. 324.

[14]n.a. “Az új földesúr.” Budapesti Hírlap. vol. XXII, no. 81., 23 Mar. 1902, p. 9.

[15]n.a. “Az új földesúr…” Ibid., p. 9.

[16]–vy. “Az új földesúr.” Magyar Nemzet, vol. XXI, no. 71, 23 Mar. 1902, p. 8.

[17]Berczeli Károlyné, editor. A Népszínház műsora… Ibid., p. 49.

[18] Lengyel, Emese. “A népszínmű története és fogalmi magyarázatok – Szakirodalmi áttekintés.” In: A Selye János Egyetem 2024-es XVI. Nemzetközi Tudományos Konferenciája – Tanulmánykötet. Komárno, Selye János Egyetem, 2024 [forthcoming].

[19] Székely György, editor-in-chief. Magyar Színházművészeti… Ibid., p. 250.

[20] n.a. “A régi szerető.” Magyarország, vol. IX, no. 117, 17 May 1902, pp. 10–11.

[21]n.a. “A régi szerető.”Hazánk. vol. IX, no. 116. 17 May 1902, pp. 10.

[22] n.a. “A régi szerető – A Népszínház bemutatója.” Budapesti Napló, vol. VII, no. 134, 17 May 1902, p. 13.

[23] Székely György, editor-in-chief. Magyar Színházművészeti… ibid., p. 201.

[24] “Katinka grófnő.” Magyar Nemzet, vol. XXIII, no. 26, 30 Jan. 1904, p. 1.

[25] n.a. “Katinka grófnő.” Ország–Világ, vol. XXV, no. 5, 31 Jan. 1904, p. 91; See also: n.a. “Katinka grófnő.” Az Újság, vol. II, no. 30, 30 Jan. 1904, pp. 13; n.a. “Katinka grófnő.” Alkotmány, vol. IX, no. 26, 30 Jan. 1904, p. 7.

[26] Mokry, Ferenc. “Katinka grófnő.” Hazánk. vol. XI, no. 27, 31 Jan. 1904, p. 8.

[27] Székely György, editor-in-chief. Magyar Színházművészeti… Ibid., p. 231.

[28] Sós, Endre. “Földes Imre.” Jelenkor, vol. IX, no. 1, 1 Jan. 1966, pp. 52–59.

[29] Sós, Endre. “Földes Imre…” ibid., p. 53.

[30] [Béldi, Izor] (-ldi). “Két Hippolit.” Pesti Hírlap, vol. XXVII, no. 14, 14 Jan. 1905, p. 7.

[31] See Fáy, Nándor. “A két Hippolit.” Független Magyarország, vol. IV, no. 1016, 14 Jan. 1905, p. 13.

[32] [Kern, Aurél] K.A. “Hűvös Iván.” A Hét, vol. XIX, no. 20, 17 May 1908, pp. 325.

[33] Merkler, Andor. “Havasi gyopár.” Magyarország–Reggeli Magyarország, vol. XVIII, no. 55, 5 Mar. 1911, p. 12.

[34] The two playbills and the list of performances can be found on the Hungarian State Opera’s website: https://digitar.opera.hu/szemely/huvos-ivan/20517/[Last accessed: 3 November 2024] For István Koósz’s bibliographical collection, see Koósz, István. A japán színház Magyarországon. Budapest, 2019, p. 150. https://mte.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Koosz-I.-A-japan-szinhaz-Magyarorszagon-bibliogr.pdf[Last accessed: 3 Nov. 2024].

[35] Székely, György, editor-in-chief. Magyar Színházművészeti… Ibid., p. 265.

[36] [Kern, Aurél] K.A. “Hűvös Iván…” Ibid., p. 325.

[37] Note on the “incompatibility” of the tramway director and the composer-poet: “We see the development of a talent toward form in this. This development also shows that this is a talent, undeniably. No one doubts this talent, except those who preach the incompatibility of capital and talent. Those who dogmatically declare that a director of an electric tramway company cannot be a composer. If Iván Hűvös’ imagination creates a melody, let him direct it as unnecessary current, transform it into a business or traffic idea, and have the company profit from it, not literature. He should never compete with the official composers, who are the exclusive beneficiaries of the five lines of the musical staff. He should not join the guild of capital because capital is inevitably dilettantish. This is not only petty but an incorrect standpoint. Dilettantism ceases to exist where creation begins. There is a phase of creation that works with ideas placed side by side, with the simple succession of thoughts, and is satisfied with this. And there is a superior form of creation that structurally connects the ideas, that creates unified structures from motifs. Iván Hűvös was not a dilettante even when he wrote his operettas with a loose succession of melodies. Because he had original ideas, creations, to which he could give form. In ballet, we already encounter structural subtleties; here, the accusations against him are even more groundless. It is true that he does not write so-called symphonic ballet, but only illustrative, situational, characteristic dance music. He does not pile up motifs, he does not go beyond a certain light level, which is the range of all his music. In this self-awareness and restraint, there is a definite artistic trait that energetically contradicts dilettantism. Iván Hűvös will prove sooner or later with his talent that, although he is a director, a landlord, and a car owner, he is, nonetheless, a poet-composer, despite it all.” [Kern, Aurél] K.A. “Hűvös Iván…” ibid., p. 325.

[38] n.a. “A csodaváza.” Ország–Világ, vol. XXIX, no. 20, 17 May 1908, pp. 403. [Béldi, Izor] (-Idi). “A csodaváza.” Pesti Hírlap, vol. XXX, no. 113, 10 May 1908, p. 9.

[39] n.d. “Siáma.” Színházi Élet, vol. II, no. 10, 9 Mar. 1913, pp. 2–4.

[40] Merkler, Andor. “Havasi gyopár.” Magyarország–Reggeli Magyarország, vol. XVIII, no. 55, 5 Mar. 1911, p. 12.

[41] Gajáry, István. “Havasi gyopár.” Az Újság, vol. IX, no. 55, 5 Mar. 1911, p. 17.; (–ldi.). “Havasi gyopár.” Pesti Hírlap, vol. XXXIII, no. 55, 5 Mar. 1911, pp. 5–6.; K. “Havasi gyopár.” Pesti Napló, vol. LXII, no. 55, 5 Mar. 1911, pp. 14–15.