Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

21 April, 2019

Is the ‘Musical Arabian Night’ in two acts by George Forrest and Robert Wright an operetta, with recycled music from Alexander Borodin? Kurt Gänzl calls 1953’s Kismet ‘one of the outstanding Broadway operettas of the postwar period’ that had a ‘long international career,’ settling itself ‘firmly into the standard English language repertoire.’ Something which the other Kismet by operetta composer Gustave Kerker didn’t manage, it premiered on Broadway in 1895 as Kismet, or: Two Tangled Turks and vanished after three weeks. Whereas Kismet with Alfred Drake managed 583 performances at Broadway’s Ziegfeld Theater, and 648 in London’s West End. It won the Tony for Best Musical, Best Libretto, Best Score, Best Male Lead (Drake).

Bernd Könnes as Hajj and Laila Salome Fischer as Lalume in “Kismet,” Neustrelitz 2019. (Photo: Tom Schweers)

As is often the case, post-WW2 Germans and Austrians demonstrated little interest in the great successes from the USA, on the one hand these were considered ‘evil’ capitalist examples of entertainment that wanted to keep the working classes quiet with fluff, just like Goebbels had done. (And we know how that ended.) On the other hand, German and Austrian operetta fans in the 1950s and 60s preferred their operettas to be more in the Strauss/Lehár vein, as propagated by the Nazis in 13 long years. So if anything, you get a 1952 recording of Strauss’ re-worked Indigo und die 40 Räuber as Tausend und eine Nacht, starring Anneliese Rothenberger (of course), Rita Streich and Helmut Krebs, Wilhelm Stephan conducts the Hamburg radio symphony orchestra.

The 1952 recording of Strauss’ “Tausend und eine Nacht” with Anneliese Rothenberger and Rita Streich.

Kismet didn’t come to a German language theater until 1977 when it was presented in provincial Koblenz. Vienna got to see it, too, at Raimund Theater under hapless artistic director Herbert Mogg, next to shows such as Die Dame im Dunkeln (Lady in the Dark), Zirkusprinzessin, Wo die Lerche singt and Robert Stolz’s Der Tanz ins Glück. Kismet didn’t make much of an impact. And it has stayed mostly off German language stages ever since, despite a new interest in ‘Oriental’ themes in the wake of Disney’s Aladdin.

The ballet company in “Kismet,” Neustrelitz 2019. (Photo: Tom Schweers)

Now, Joachim Kümmeritz, the parting intendant in Neustrelitz (one and a half hours north of Berlin), has put Kismet on stage at his small theater – a theater company that has a full symphonic orchestra able to play the fabulous Arthur Kay orchestrations; they also have a chorus and a ballet company. In other words they have many things even the most lavish Broadway production does not have these days. So is this a chance to outshine the competition?

It would definitely have been, if there had been a conductor at hand who had any feeling for bounce, sparkle, lavishness, rhythmic drive. Sadly, young Daniel Strateiwsky is not that person. He allows for an adequate reading of the score by the Neubrandenburger Philharmonie, but they never knock you off the seat with the sweeping melodies (taken from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor and his famous Polovtsian Dances), nor with the wild percussion sections. That is unforgivable, because Mr. Strateiwsky has the forces there in the pit, but he doesn’t utilize them. Interestingly, the Arthur Kay orchestrations are so brilliant that they work anyway and manage to create their magic. (I’d call that genius.)

“Stranger in Paradise”: Laura Scherwitzl as Marsinah and Andrés Felipe Orozco as the Caliph in “Kismet,” Neustrelitz 2019. (Photo: Tom Schweers)

The staging was done by operetta expert Wolfgang Dosch who has put the fairy tale story onto the stage – with the help of dramaturg Lür Jaenike, costumes and sets by Susanne Thomasberger, and choreography by Alexandre Tourinho – in a straight forward fashion. The result is colorful; it’s also hard to pin down. I sat in the performance and wondered if this Kismet could have played like this in 1969, 1979, 1989, or 1999, with anyone noticing that it’s actually from 2019? It’s like time travel, which you can see as a big plus, or a real drawback. I am still not sure which I’d opt for. (Maybe because I like and admire Mr. Dosch very much as a researcher and operetta crusader.)

There are some wonderfully ‘timeless’ soloists, chief among them the two women: Laura Scherwitzl is a ravishing Marsinah who produces lovely tones in “Baubles, Bangles, and Beads” and even more so in “This is my Beloved.” With the help of microphones and great amplification she soars, and looks magnificent standing on a sand dune with a full moon behind her. A person in the stalls shouted a loud “wow” when Miss Scherwitzl finished “And this is my beloved,” a true goose bump moment; as it should be.

The other outstanding performance comes from Laila Salome Fischer as Lalume, who looks dazzling and sings her “Not Since Nineveh” with splendor – with a lusty middle range and secure top. She clearly enjoys playing the vamp. And I wish the stage director had given her more nuanced things to do than walk up and down the stage waving her veil in standard fashion.

Bernd Könnes (l.) as Hajj and Sebastian Naglatzki as the Wazir in “Kismet,” Neustrelitz 2019. (Photo: Tom Schweers)

Talking of standard things: there are many stereotypes in this show that some, today, would label ‘racist.’ Of course, they are typical for the way people in the USA saw the Arab world back in 1953. It’s not how we see it now. How do you deal with that? Wolfgang Dosch (and his dramaturg) pretend there are no critical debates, they play every line without blinking an eye. Maybe hoping that no one will notice? While I’m not advocating a total deconstruction of the script, I would have valued more critical reflection. And at the very least, an ironic approach to the many stereotypes, making them fun and making it clear that we cannot take them seriously anymore.

To do that you would have needed a different male cast, able to handle comedy. In Neustrelitz the male leads sounded mostly provincial, not updated versions of Alfred Drake or Richard Kiley (let alone Howard Keel or Vic Damone). Bernd Könnes is the house tenor, his Hajj is adequately sung, but no star turn. Which it must be to make the show work.

Sebastian Naglatzki as the towering Wazir is too young to be spooky and believable. And Andrés Felipe Orozo as the Caliph is the most unsensual operetta tenor I can imagine. Which turns “Stranger in Paradise” into a rather one-sided affair.

To be fair, singing Kismet is probably not what any of them trained for. But: Robert Merrill, Samuel Ramey, Julia Migenes and others have demonstrated that opera people can handle this score well, as well as Drake & Co. (Remember the Mantovani recording, with Merrill teamed up with Regina Resnik as Lalume, plus Adele Leigh as Marsinah and Kenneth McKellar as the Caliph?)

Andrés Felipe Orozco as the Calip singing “Night of My Nights” in “Kismet,” Neustrelitz 2019. (Foto: Tom Schweers)

On the plus side of things, you get to hear all the ballet music in Neustrelitz, including the “Dance of the Three Princess of Abadu,” and you get to see the local ballet company with some impressive natural V-shapes on display. It made me wonder what they would look like with someone like Otto Pichler in charge.

Amazingly, this performance on Easter Saturday was sold out. Locals of all age groups flocked to it, and apparently they enjoyed it. There was immense cheering. And the elderly lady sitting next to me asked my English speaking companion if we were on holiday in the region – she was clearly delighted that someone from ‘outside’ found the way to her theater company. She also didn’t much mind that the fabulous lyrics by Wright/Forrest were turned into a not quite so fabulous German text by Janne Furch that was hardly intelligible, because none of the soloists bothered with clear pronunciation or word play. (There are no supertitles.)

The theater in Neustrelitz. (Photo: Private)

Still, the Neustrelitz Kismet deserves attention because the show invites us to reflect so many things, most of all about how we want to see the Arab world in times of culture wars, terrorism, debates about religious fundamentalism and women’s right, cultural appropriation etc. Kismet has a lot to say about all these things, almost like the TV series Mad Men: you marvel at how things once were, but are not anymore. Mad Men managed to generate energy from that, Kismet can do the same.

Advertisment for the 2019 “Kismet” production in Neustrelitz. (Photo: Private)

As an operetta-to-rediscover in Germany and Austria Kismet is probably better suited than Arabian Nights by Carmen Lombardo and John Jacob Loeb, a 1952 “musical extravaganza” that starred Lauritz Melchior as the Sultan at Jones Beach Theatre. In the recent CD release you get a highly personal essay by the late Richard Traubner who was clearly in love with the show. It’s also easier to digest than The Beastly Bombing: A Terrible Tale of Terrorists Tamed by the Tagles of True Love, though that 2006 Julian Nitzberg/Roger Neill show addresses all of the political aspects mentioned above, and manages to put them into the best modern day operetta I know.

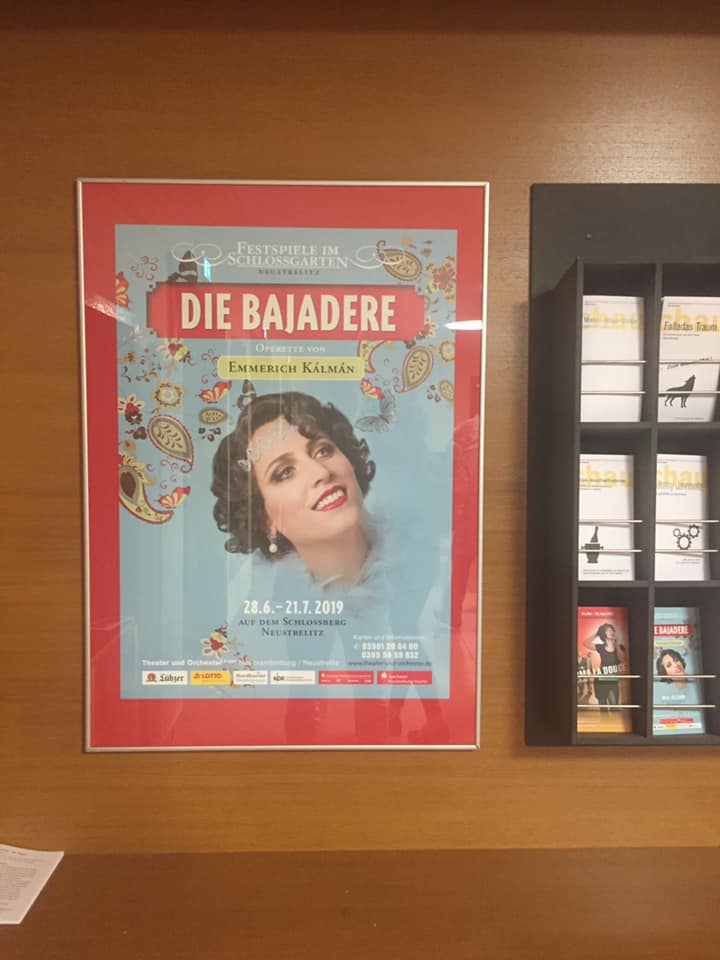

Poster announcing the 2019 summer production of “Die Bajadere” in Neustrelitz. (Photo: Private)

Whether the new intendant in Neustrelitz, Sven Müller, will explore such repertoire further remains to be seen. As his farewell production, Müller’s predecessor Joachim Kümmritz offers another ‘exotic’ show this summer: Kálmán’s Die Bajadere is the title chosen for the 2019 open-air operetta festival in Neustrelitz.

For more information and perfomance dates, click here.

I was in tge Kismet production in Koblenz. The beautiful Marsunah was Hildegard Bobb.

Wright and Forest were there so met and worked eith them. Trying to recall the orchestra conducter.

Barbara