Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

Originally produced at Baden-Baden during the 1869 summer season, with the young Mdlle Périer in its principal travesty rôle, La Princesse de Trébizonde proved successful enough that Offenbach and his librettists subsequently expanded it into a full evening’s entertainment and, later in the same year, at the same time that Les Brigands was being mounted at the Théâtre des Variétés, La Princesse de Trébizonde was staged at the Bouffes-Parisiens. Étienne Tréfeu and Charles Nuitter’s libretto made use of the already over-used doll-girl motif, but they surrounded that motif with such jolly characters and scenes as to make it seem less stageworn. As a result, the piece survived, alongside the ballet Coppélia and Audran’s La Poupée, as the happiest example of that eternal 19th-century plot on the musical stage.

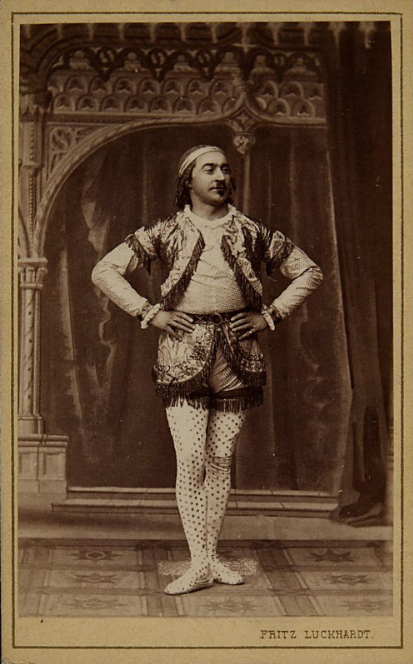

Josef Matras as Prinz Casimir in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt”, Carltheater Vienna. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

Sparadrap (Édouard Georges), the eagle-eyed tutor of the pubescent Prince Raphaël (Anna van Ghell), allows him to visit the waxworks run by Cabriolo (Desiré), unaware that the mountebank’s daughter Zanetta (Mlle Fonti) is standing in for a broken doll. When Cabriolo wins a chateau in the fair’s lottery, and Raphaël’s family turn out to be their new neighbours, the prince’s ultra-careful father, Prince Casimir (Berthelier), is delighted to see that his son’s youthful passions are limited to the next-door folks’ doll and he promptly takes the waxworks and their proprietors back to court. When Casimir discovers that his son has known for an act and a half that Zanetta was not made of wax, the boy brings out his dad’s old and indiscreet diaries, which he has been using as his guide-lines to growing up, and father is obliged to mutter away into consent. Céline Chaumont starred as Zanetta’s sister, Régina, in love with the aristocrat-turned-servant, Trémolini (Bonnet), who becomes first the company’s fair-barker and then (because of his knowledge of aristocratic etiquette) their butler, and Mlle Thierret played the plum female comedy rôle of Cabriolo’s sister, Paola, who suffers from delusions of royal relationships.

Costume for Sparadrap in “La Princesse de Trébizonde” by Draner.

In line with its libretto, the score of La Princesse de Trébizonde, although fashionably labelled as opéra-bouffe, had a little less of the zany freedom of music of Offenbach’s earliest and genuine opéras-bouffes. Some touches of the burlesque element were still there – the first-act finale, with Cabriolo and his family bidding farewell to their old sideshow (‘Adieu, baraque héreditaire’) in one of the happiest pieces of the score was a direct parody of Rossini’s Guglielmo Tell – but the fun and Offenbachian melody in Casimir’s smoke-from-the-ears description of his easily fired temper (‘Me maquillé-je comme on dit’), Régina’s song about her tightrope act (‘Quand je suis sur la corde raide’), Zanetta’s Ronde de la Princesse de Trébizonde, and in Raphaël’s repeated raptures, both with and over his ‘doll’, was often rather less ‘bouffe’ than elsewhere.

The success of La Princesse de Trébizonde was barely overshadowed by that of Les Brigands, and it stayed at the Bouffes for some four months as a first run. It was revived there, after the interruptive Franco-Prussian War, in 1875 (14 February) with Louise Théo as Régina, again in 1876 (September) with Daubray as Cabriolo and Paola Marié as Régina, and was given a new production at the Théâtre des Variétés in 1888 (15 May) with a cast headed by Mily-Meyer, Mary Albert, Cooper and Christian. The record thus established was a highly satisfactory one, in the terms of any other composer, yet La Princesse de Trébizonde remained and remains a little in the shadow of the more celebrated Offenbach works in France where it has been rarely heard from since that last Paris revival.

Sheet music cover of a “quadrille brillant” put together by Strauss with tunes from Offenbach’s “Princesse de Trébizonde.”

Something of the same thing happened in London where the show, nevertheless, had a fine first production (ad Charles Lamb Kenney) under John Hollingshead’s management, at the Gaiety Theatre. Nellie Farren was Régina and J L Toole ad-libbed freely as Cabriolo, at the head of a cast which included Robert Soutar (Casimir), Constance Loseby (Raphaël) and Annie Tremaine (Zanetta) and the show stayed in the bill for a little under three months, was brought back later in the same year, was toured and then played again at the Gaiety in 1872 (19 April) in Toole’s repertoire. The British provinces actually saw as much or more of The Princess of Trébizonde as of any other Offenbach piece, for in 1871 the enterprising Henry Leslie of Liverpool’s Prince of Wales Theatre sent out a touring company, led by Augusta Thomson, Edward Chessman and the young Henry Bracy, and that company toured almost non-stop round the country for years. Later (1876) Chessman took the show out himself, followed in 1881 by Joseph Eldred, and more than a decade down the line the Leslie production (with some of its original cast!) was still spottable on the British road.

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897.

In 1879 the show was given a spectacular revival at the Alhambra with Charles Collette (Cabriolo), J Furneaux Cook (Casimir), Miss Loseby (Raphaël), Alice May (Zanetta) and Emma Chambers (Régina), and an ‘Automatic Ballet’ of wax dolls introduced in the final act. But the 1880s seemingly saw the show out. Other pieces from the era survived into further reproductions, and even up to the presentish day, but this one didn’t.

Lydia Thompson in a formal portrait.

La Princesse de Trébizonde was introduced to America in Kenney’s English version in a production at Wallack’s Theater which presented the unusual feature of starring the famous burlesquer Lydia Thompson (Régina) in a French opéra-bouffe rôle. Lydia admitted that the piece had been ‘rewritten and adapted from’ the original, and she went so far as to introduce music from La Belle Hélène into the action, but much of what was seen seems to have been the real thing. Camille Dubois played Zanetta, Carlotta Zerbini was Raphaël and Harry Becket took the rôle of Cabriolo, but in true burlesque fashion Willie Edouin played Manola (ie Paola) in travesty, as did Hetty Tracy as Tremolina (sic). New York quickly pronounced that it preferred blonde Lydia in traditional burlesque. Aimée appeared in French breeches as Prince Raphaël in 1874, but, in spite of its rather curious beginning, the piece prospered in America in translation rather than in the original French. It was added to the Alice Oates repertoire in 1878, produced at the Casino Theater (5 May 1883) with a top cast including John Howson, Lillian Russell, Digby Bell and Laura Joyce, played in German at the Thalia Theater (14 December 1882), again at the Casino with Marie Jansen and Francis Wilson (15 October 1883), at Koster & Bial’s – decorated with acts – in 1886 (22 February) and, in a heavily revised version, with Pauline Hall and Fred Solomon starred, at Harrigan’s Theater in 1894 (5 March). In 1898 Milton Aborn’s company produced it in summer season under the title The Circus Clown. And then America, too, cried enough.

Josefine Gallmeyer in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt,” Vienna. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt also won a good reception in Germany, but it was in Austria that the piece found most particular favour. Produced at the Carltheater (ad Julius Hopp) with a very strong cast headed by Josefine Gallmeyer (Régina), Hermine Meyerhoff (Zanetta), Karoline Tellheim (Raphaël), Josef Matras (Casimir), Karl Blasel (Cabriolo), Wilhelm Knaack (Sparadrap) and Therese Schäfer (Paola) and conducted by Offenbach himself, it was immediately seen to be one of the theatre’s biggest-ever successes. It was played 53 times between March and May, came back in the spring to reach its 72nd night by the new year, passed its 100th in repertoire on 24 June 1873, its 125th on 13 September 1874, and reached its 141st on 28 May 1878.

Josefine Gallmeyer in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt,” Vienna. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

It was given for ten performances at the Theater an der Wien in 1885 (17 January) with Ottilie Collin (Raphaël), Karl Blasel, Friese (Casimir), Rosa Streitmann (Zanetta) and Maria Theresia Massa (Zanetta), it was revived at the Carltheater, with Blasel, Knaack, Anna von Boskay and Frln Tornay in 1892, played in 1899 at the Jantschtheater and in 1905 at the Theater in der Josefstadt.

Karl Blasel in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt.” (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

However, unlike elsewhere, Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt did not then disappear. It was played at the Berlin Opera in 1932, and has been seen in Vienna at the Theater an der Wien (12 May 1966) and at the Wiener Kammeroper in the 1980s. Berlin’s Theater des Westens hosted a revival in 1904 (8 April) with Wellhof and Frln Döninger featured.

In Budapest (ad Endre Latabár), where it was first seen in 1871, the show was later taken briefly into the repertoire of the Népszinház (18 May 1876, 5 performances), and it was also played in many other European centres (Brussels, Naples, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Prague, Bucharest, Zagreb etc), as well as in Australia where William Lyster introduced it in 1874, but it seems to have survived best and only where the taste for the less extravagantly burlesque operettic works is the strongest.

Wilhelm Knaack in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt”, Carltheater. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

UK: Gaiety Theatre The Princess of Trébizonde 16 April 1870; Austria: Carltheater Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt 18 March 1871; Germany: Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt 30 June 1871; USA: Wallack’s Theater 11 September 1871; Australia: Prince of Wales Theatre, Melbourne 22 June 1874; Hungary; Budai Színkör A Trapezunti hercegnö 17 September 1871

By all accounts from Vienna: Miss Gallmeyer seems to have been very extravagantly ‘burlesque’ in the title role, which is luckily documented in a great many photographs. So, as usual, it’s a question of how you perform your Offenbach ‘classics.’ Personally, I’d vote for the over-the-top Gallmeyer approach, always. Considering that the show was especially successful in Vienna (with Miss G) that might be the best way to go.

Well, no: It’s a touching musical story about innocence. About a prince who falls in love with a doll (there are hilarious puns in the dialogue: une princesse du cire). That’s why the female choir of multiplied Cherubino-pages pokes fun of him in a most romantically ironic way at the beginning of act 3 (!: 2nd version; that’s an example of the typical Offenbach female act openers you also have in Fantasio, Périchole, Geneviève du Brabant, Vie parisienne etc.). And that’s why he has a most brutal father introduced by a hilarious couplet du canne in act 2. It was not by chance that great Jürgen Fehling did choose this piece for his annual christmas pantomime production at the Städtische Oper Berlin (Charlottenburg) as a “gift” to the “Neo-Prussian” vulgo Nazi reaction in 1932.

I don’t think, it’s about sauciness (except the typical travesty roles and the colombina skirts allowing the male audiences to look at the legs of the ladies). It’s a satire on the start up fantasies of the bourgeoisie and as always with Offenbach at these times it’s about his anxieties about violence and war.

As always, Mons/HerrOffenbacn is credited/blamed for the work of his (brilliant) librettists.