Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

21 August, 2018

In a recent article for The Times, Jamie Stoker reported on casting for London’s Magic Mike Live. The headline says “Tops Off for the Girls,” and right under that: “Is objectification of naked men still acceptable?” Well, you could ask what ‘still’ is referring to in this context. Are we looking at centuries of men being objectified by women: openly, unabashedly, lustfully? Were male performers ever objectified in operettas, comparable to a live strip show that’s sold as an 18+ event in the West End today? Here’s a short history of male stars in operettas as objects of desire for adoring female fans.

Let’s start with the venue in which Magic Mike Live can be experienced: “The Theatre at the Hippodrome Casino is being transformed into an intimate, state of the art, magical new home for the show which is based on the smash hit films Magic Mike and Magic Mike XXL.” That’s what you learn on the show’s official homepage. Of course, the Hippodrome (in its latest version) stands just around the corner from where the nineteenth-century Alhambra used to be. And the Alhambra, both as a theatre and as a variety house, was a rather notorious place. Not only did it present very undressed and very young ladies on the stage – literally ‘fishing’ for gents in the audience with a fishing rod, to musical accompaniment – but it was also a pick-up place for ‘musical’ men looking for other men.

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897.

There was a gallery at the rear and a promenade for prostitutes, male prostitutes that is. You can read about them in Glenn Chandler’s 2016 documentary ‘novel’ The Sins of Jack Saul. (Yes, that’s the Jack Saul of the Cleveland Street scandal.) While the homosexually inclined gentlemen back in Victorian times got their kicks from men off stage, while listening to operetta and other types of music, and the heterosexually inclined gents got their kicks on stage (and had to wait for the ladies at the stage door, instead of humping them in the darkness of a top tier gallery), there were famous examples of men on stage attracting lusty glances, too. Officially from the ladies in the audience who were an important element in the entertainment business. Because wherever the ladies went, heterosexual men followed.

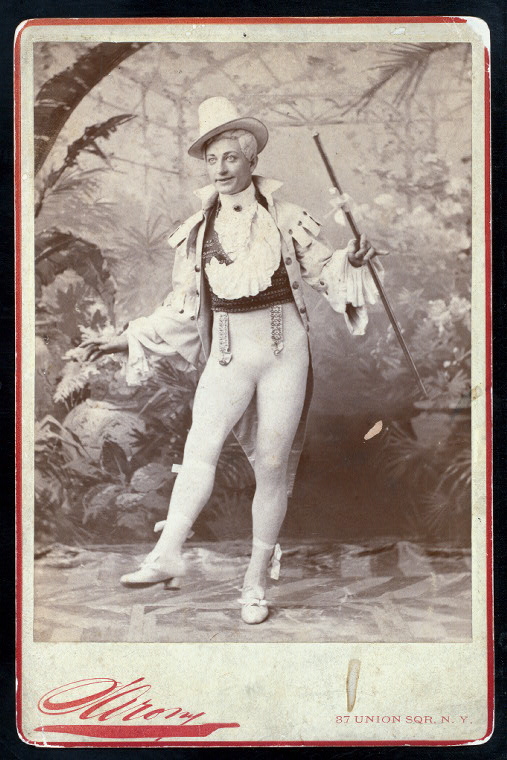

C. D. Marius as Landry: the “masculine masher” in Hervé’s “Chilpèric.”

In her memoirs, 19th century operetta superstar Emily Soldene writes about the young French actor Claude Marius playing Landry, in 1860s London, in Hervé’s medieval romp Chilpéric. Is Soldene objectifying the young man when she states:

Young and beautiful, and slender, and sleek, and sly and so elegant. An ideal Cherubino but, I am afraid, even more susceptible than the operatically historical and love-stricken young person. He played Landry, and made love to Frédégonde or Brunehaut, he didn’t care which, with an ardour that was not only particularly French, but particularly pleasing and particularly successful, so successful indeed that every girl in the front of the house was seized with a wild desire to understudy those two erratic, not to say imprudent characters. He certainly looked awfully nice, his figure being perfection.

Henry E. Dixey in “Adonis,” 1884, photographed by Sarony.

On the other side of the Atlantic, on Broadway, there was the equally attractive Henry E. Dixey who made a big splash as Adonis. The musical is Australian playwright Willie Gill’s burlesque of the tale of Suppé’s Die schöne Galathée. Instead of a female statue who comes to life, here, we have a male statue. In her article “Boylesque in a Nutchell” Trixie Little writes:

The very first performer qualified as Boylesque, is known as Henry E. Dixey, an American actor who began to act in the [burlesque/operetta] Adonis in 1884, in which he had the role of a Knight statute. The sculptor, a woman, was so proud of her work that she fell in love with it and refused to give it to the duchess and her daughters who had ordered it. As they couldn’t agree on who would keep the statute, they decide to bring the knight to life, so he could decides with who he would like to live. Then begins the high life for him, but disappointed by it, the gentleman decides he wants to stay a statute. The [show] was played more than 600 times on Broadway, which was the longest run for a play at the time. The vision of the actor’s legs in his tights, which was quite unusual then, was a part of the success of the play especially among women.

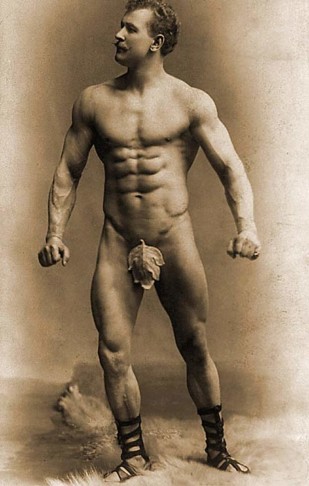

A little later, Florence Ziegfeld discovered that he could get high society ladies to come to his shows by presenting Eugene Sandow: he performed ‘Muscles Exhibitions’ wearing only a leaf, and after bathing in cold water used to walk in the audience so they could watch, touch and discuss the muscles of the man who would become Ziegfeld’s first mega-star, while Ziegeld himself would go on to become a major influencer of operetta and revue operetta.

Eugen Sandow in 1894.

Does Mr. Sandow count as an example of an objectified male performer? He certainly took his “tops off for the girls.” Not just his tops, as a matter of fact. And not just for the girls. In his biography The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow (2011) we learn that “numerous romantic overtures [were] made to him by men and women alike.” If you count Eugen Sandow in, you could ask whether the “objectification of naked men is still acceptable”? Then again, no one asked about objectification back then. The word hadn’t even been dreamed up. But times have changed.

Poster for “The Sandow Trocadero Vaudevilles,” produced by Ziegfeld in 1894.

In his article Jamie Stoker writes: “Magic Mike Live, you see, is all about female empowerment, which might sound puzzling until you realize you’re in a room of men about to humiliate themselves en masse. Perhaps, I think, this is how the patriarchy will finally be taken down – death by a thousand bad twerks.”

Did anyone look at C. D. Marius, Henry E. Dixey, or Eugene Sandow, from a “female empowerment” perspective?

At the Magic Mike auditions, Mr. Stoker meets a young man called Jamie who had worked for Disney for the past few years, waving in parades as Prince Charming. He’s not bothered about getting topless for the show: “Most of my Instagram is that anyway.”

You might ask whether thumping the floor, peeling off their vests and dusting their crotches suggestively (“Hand on your shit!” screams the choreographer at her dancers at the Magic Mike auditions) might be inspirational for operetta folks, too? Of course, Barrie Kosky together with choreographer Otto Pichler has inserted thumping topless muscle boys into all of his successful operetta productions. (Apart from Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will, which is without chorus and ballet in the Kosky version.)

But if you look at the average operetta production in Mörbisch, Ischl, Wooster, or the Metropolitan Opera you won’t have to contemplate questions of objectification. Not even of the female performers. It seems most operetta productions these days shy away from anything that could be even remotely ‘topless.’

Does that have to do with the #metoo debate? Not really, since the neo-prudery regarding operetta performances spread long before anyone in the post-WW2 operetta world could shout “me too”. And obviously sexual harassment is not the same as objectifying someone, but the current discussions tend of blurr the boundaries. And where do you draw the line between objectification and sexism? And if you start that discussion, how important are ageism or ableism in an operetta context?

German bass-barihunk Georg Festl, who performs in “Fledermaus” at Staatstheater Darmstadt, as presented by the blog “Barikunks.” (Photo: barihunks.blogspot.com)

Do operetta performers today have Instagram accounts? Do they present themselves à la Jamie-Prince-Charming? What would Claude Marius, Henry E. Dixey and Eugene Sandow show on Instagram if they were alive today? Would it empower anyone to see them in all of their revealed glory? Did it bring down the patriarchy back in the nineteenth century to have them strut their stuff for the ladies? Could it do so now? Is a debate about objectification in operetta overdue, and would objectification in operetta do the genre any good? Would it attract new audiences to have the likes of Mr. Sandow – in modern-day equivalents such as Channing Tatum, Alex Pettyfer, Joe Manganiello, or Matt Bomer – cast in an operetta production today, let’s say as Danilo in The Merry Widow or Tassilo in Countess Maritza? Or to have someone like Claude Marius of who Emily Soldene writes, “And how clever he was! And how he managed what he was pleased to call ‘his voice’. It was not singing, but ‘he got there all the same’”? Would an 18+ production of operetta bring the genre back to its original 19th century glory, the kind of glory that Emily Soldene and so many others described (often in moral ‘outrage’)?

The crew of the “HMS Pinafore” at the Young Vic: (left to right) CJ Hartung, Joshua Hughes, Jeffrey Williams, John Kaneklides, and with flag. (Photo: Barihunks Blog)

So many questions. And possibly just as many answers if someone would bother to openly ask and discuss these points, re-examiming the careers of operetta performers with regard to categories such as sexism, ageism, ableism. The topics of objectification and female empowerment are hot topics, too, and operetta history has a lot to say about them, certainly with regard to the many ‘strong’ women in operettas who broke free from patriarchal oppression and went their own self defined way (just think of Offenbach’s star performer Hortense Schneider and roles written for her, such as the Grand Duchess of Gerolstein).

And while Magic Mike Live is still officially targeted at a heterosexual female audience (“Photo ID must be presented on arrival at the venue”), the operetta world has always been more diverse from the early days of Hervé onwards. It has offered sexy male performers for the pleasure of gentlemen in the auditorium, too. Remember Erik Charell claiming, in the mid 1920s, that the world has become “Greek” again, only to have a group of lusty Tyrolean boys storm onto the stage and do a slap dance (with strong “Grecian” undertones!) that would put any Magic Mike performance to shame.

The “Tiroler Gruppe” as Charell originally used them in “Für Dich” 1925.

It didn’t harm operetta history: Im weißen Rössl is still one of the most successful titles of all time, and the Tyroleans doing “Greek” gymnastics played no small part in that. And in that show the ballet boys and girls got fully undressed for a scandalous swimming scene in act 2, something which the Nazis considered the height of indecency. Indeed, it was. And I wish such indecency would make a big comeback in operetta, instead of Magic Mike.

For more information in Magic Mike Live in London, click here.