Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 July, 2019

It is one of the more amazing developments of recent years that suddenly “entertainment” is included in major exhibitions dealing with history, in this context operetta titles suddenly pop up where they had been excluded for decades and decades. One example in 2019 was the exhibition at Berlin’s Museum of Photography about the 1918/19 revolution in Germany that led to the founding of the Weimar Republic. Another recent example is the much discussed show Le Modèle Noir at the Orsay Museum in Paris.

The cover for the catalogue “Le Modéle Noir,” Orsay Museum 2019

In this show about the representation of Black People in French art history “from Géricault to Matisse” Offenbach’s La Créole is included, in the context of Josephine Baker playing the “dusky Guadaloupean” called Dora, a role created by Anna Judic in 1875 at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens.

Photo of Josephine Baker from the exhibition “Le Modéle Noir” at Orsay Museum, 2019.

It tells the story of “black faced” Miss Judic as Dora, arriving in France by ship and sorting out the amorous chaos between Antoinette and René (a breeches role for Anna van Ghell), and between René’s friend Frontignac and Dora herself. Along the way Dora gets to sing a lively chanson about the dames of Bordeaux and romances such as “Il vous souvient de moi, j’éspère.”

The original production lasted 60 performances in Paris, but because the name Offenbach was attached to it, there was a successful production in London in a slimmed-down version with Kate Munroe as the Créole. In Vienna, Marie Geistinger put on heavy make up for the title role, at a time when dark skin was seen by many Westerners as “exotic” and “alluring.” Which made the already fetishized diva – who was the blond, white and nude Belle Hélène in Vienna – even more desirable.

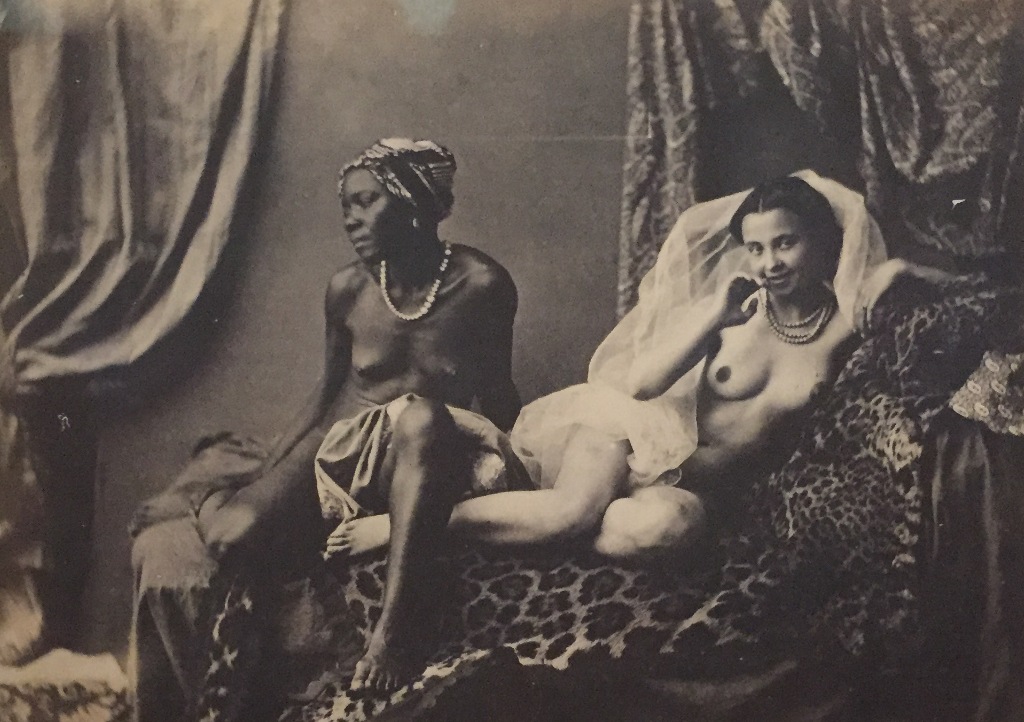

Black prostitutes shown in Félix-Jacques Moulins “Études photographiques: l’Odalisque et son esclave,” 1853.

The recent Paris exhibition documented the erotic allure that black women (and men) had for many with photos of black prostitutes who were seen as especially desirable because sexually “wild.” At least that was the cliché many today would label “racist.” Just like the practice of black facing is seen as such, though the libretto by Albert Millaud is not in any noticeable way catering to racist ideas. And the idea that the operetta prima donna is highly desirable and sexually available is completely independent of skin color. One could ask if a painted black body is just another “costume” for operetta divas of the time to wear to show off?

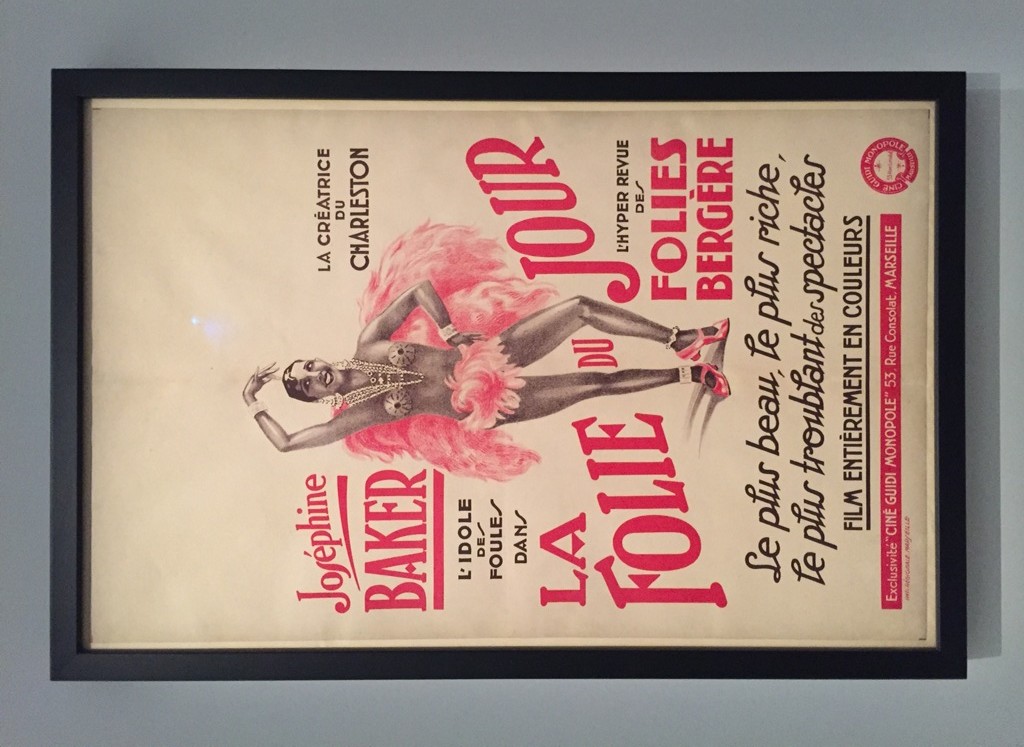

In the 1920s and 30s Josephine Baker caused a sensation with her revue performances in Europe, most notably in Paris. And she certainly showed as much naked flesh as the various 19th century operetta prima donnas.

Josephine Baker shown on a poster of the Folies Bergére in Paris.

It was for Miss Baker that the producers of the Théâtre Marigny commissioned a re-write of La Créole from Albert Willemetz and Georges Delance. It premiered in 1934 and included various new roles, most importantly it brought Miss Baker on right away in act 1 – and not, like in the Offenbach original, in act 2.

A doll showing Josephine Baker in pink feathers, as seen in “Le Modèle Noir” at the Orsay Museum 2019.

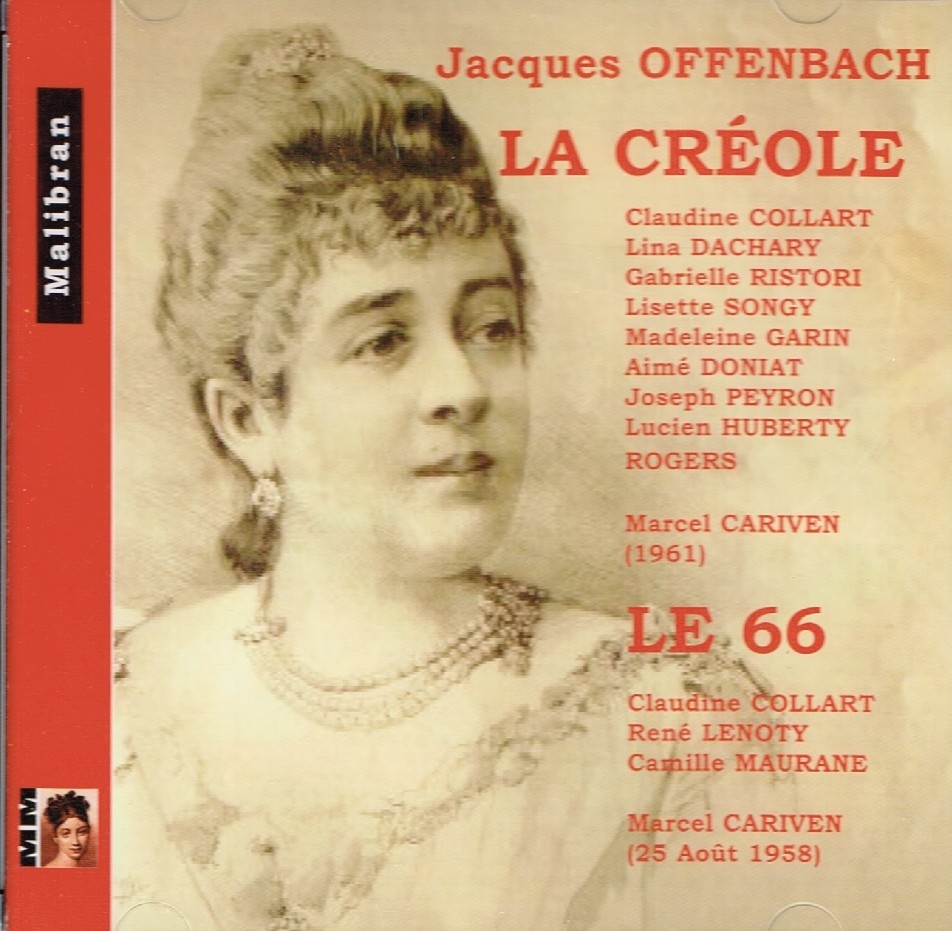

According to Kurt Gänzl’s Enyclopedia of the Musical Theatre there is a recording from 1934, though I haven’t seen that on sale anywhere. There is, however, a re-issued recording featuring Lina Dachary that makes me long to hear the show in a full modern stage production addressing the various “black stereotypes” and all the related aspects, maybe also demonstrating how things have changed from 1875.

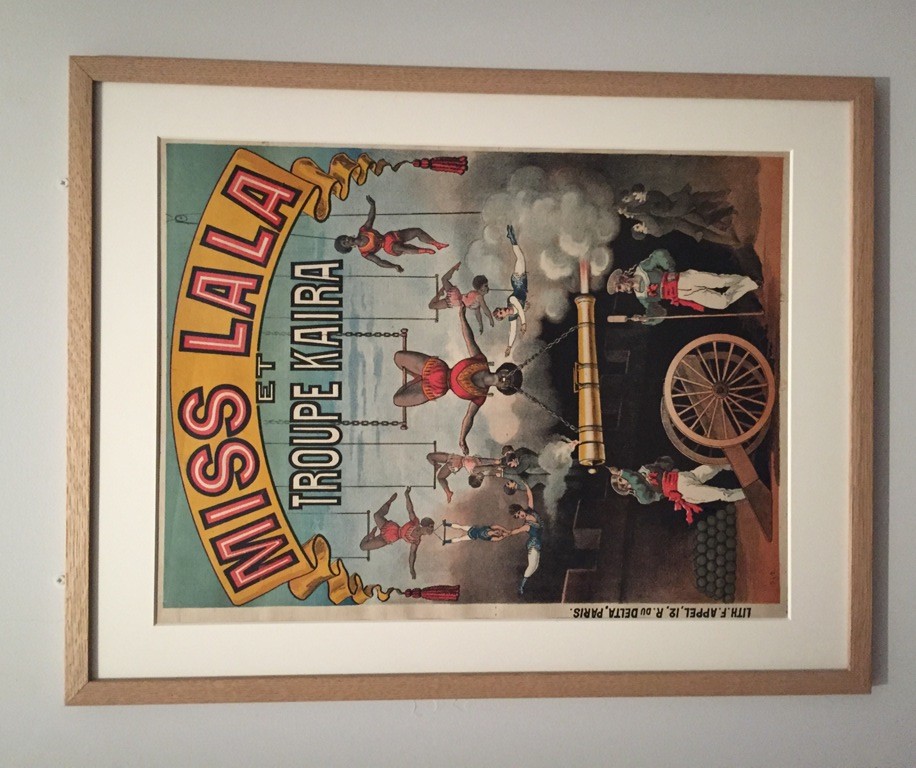

Poster for Miss Lala’s circus act, as seen in the exhibition “Le Modèle Noir” at the Orsay Museum, 2019.

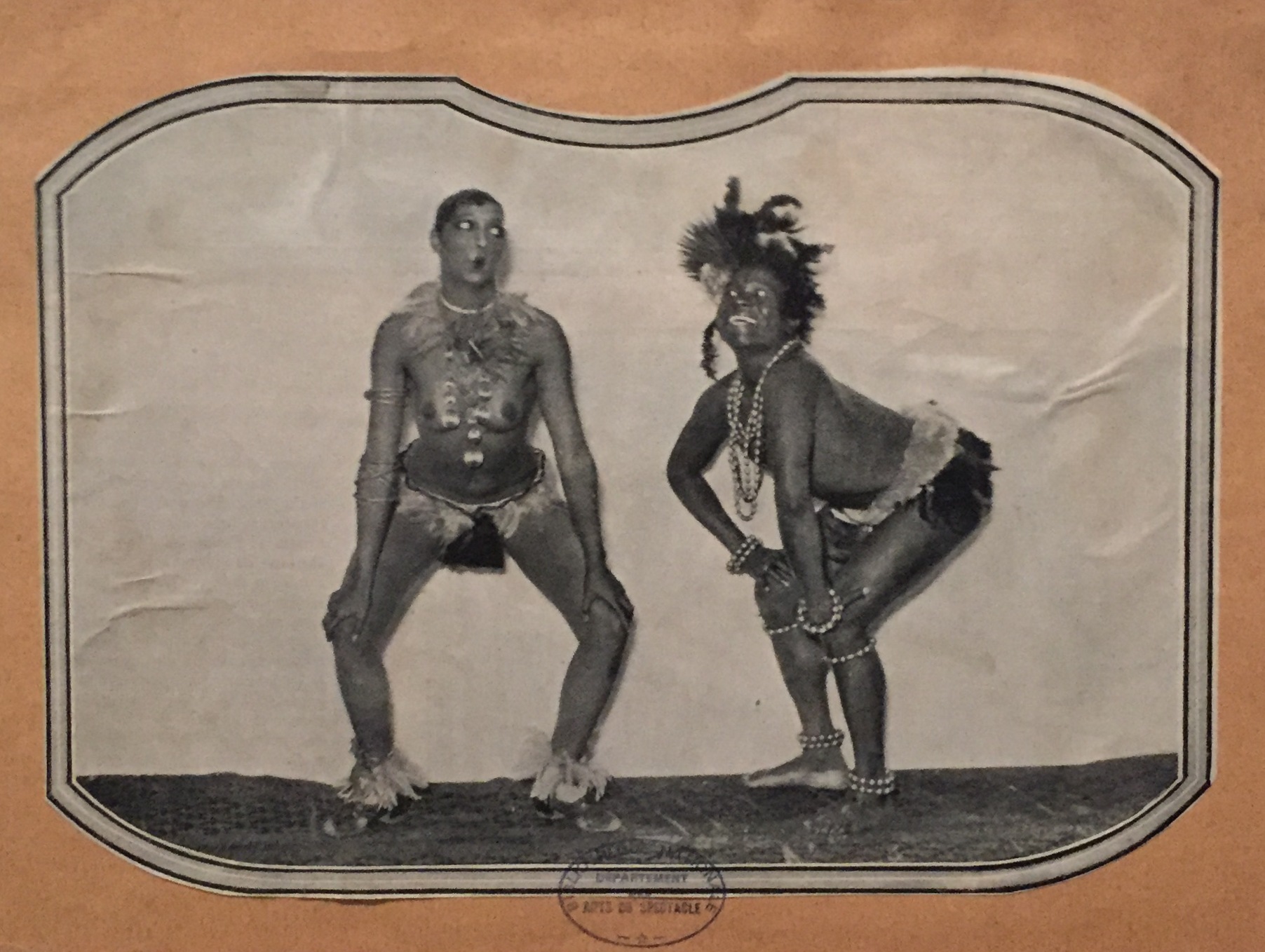

The chronology of representation was quite brilliantly done by the Orsay Museum, showing – with regard to the entertainment world – how black performers found their way into circus acts.

The exhibition also highlights the life and career of the clown called “Chocolat” whose story has recently been turned into a movie entitled Monsieur Chocolat and starring Omar Sy.

While the successful exhibition was in French and English, the voluminous catalogue of 380+ pages is only available in French. Which is somewhat shocking considering that the Orsay Museum is an international institution and the topic of representation of People of Color and blacks in particular is one that’s interesting for a very wide audience – which was clear to me as I visited the exhibition and saw the very international crowd.

Cover for the Malibran version of “La Créole” featuring Lina Dachary.

While I am still waiting for that English edition of the catalogue, I recommend the re-issued Créole recording on Malibran, combined with Offenbach’s Le 66. And if the Josephine Baker recording(s) show up anywhere, please send them my way.

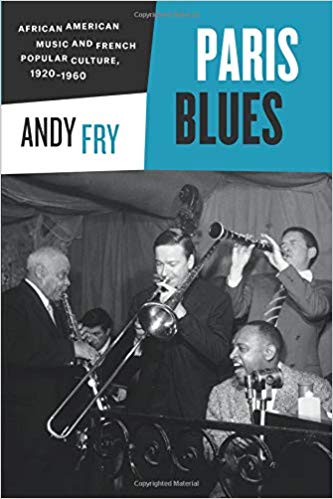

Andy Frys book “Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960,” published by University of Chicago Press in 2014.

By the way, there is an English language book by Andy Fry that includes a chapter called “Du jazz hot à La Créole” about Josephine Baker. There we read: “Wrapping original and revised texts, reception and biography together in the operetta’s plot, [the book] considers how the same tensions as characterized French reactions to ‘others’ and their. La Créole at once completed the construction, and tested the limits, of a complex redefinition of Baker as French. If most observers saw Baker’s transformation as an affirmation of France’s ‘civilizing mission,’ the few dissenters paradoxically risked insisting on her difference in terms of an essentialized blackness. A comparison with other musical treatments of a similar story (Carmen, Madama Butterfly) and contemporary Baker films (Princesse Tam-Tam, Zouzou) reveal the unhappy logic of their argument. Recognizing both ‘savage’ and ‘civilized’ personas as witty performances relocates Baker’s agency. It may even help to move beyond fixed racial categories to dynamic cultural processes: ‘creolization.’ While Baker was highly skilled at mediating audience expectations, however, the Créole chapter concludes that she was never wholly able to escape them.”

It would be great if operettas such as La Créole could be included in today’s discussions about representation, and the problems of racial stereotypes past and present. It would also be great if such a discussion would not immediately lead to screaming and wild accusations (on both sides).