Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

13 May, 2009

When composer Ralph Benatzky (1884-1957) – fresh from his international triumphs with Casanova, The Three Musketeers and White Horse Inn – signed a contract with publisher Georg Marton in September 1933 for a new musical and political farce based on the comedy Margarete von Navarra (by Ladislaus Fodor) times were not exactly rosy for operetta composers in Germany. The Nazis had come to power in January 1933 and had begun to ‘clean up’ the predominately Jewish entertainment world radically.

Composer Ralph Benatzky in the 1930s. (Photo: Archive of the Operetta Research Center.)

As a consequence, many actors, authors and composers had fled from Germany and based themselves in Vienna, the other great German-language operetta metropolis of the era. Though Benatzky himself was Christian, most of his preferred interpreters (and his wife) were Jewish. Having been an ardent opponent of the Nazis from the mid-Twenties, Benatzky shifted the center of his activities from Berlin to Vienna too, and tried to find new paths for writing operettas – leaving behind the massive revues that had made him famous in the 1920s and opting for smaller scale, more intellectual, more cabaret-style forms of operetta. He scored great successes with the shows composed in that ‘new’ vein, e.g. Adieu Mimi, Das kleine Café, Bezauberndes Fräulein and Meine Schwester und ich.

In 1934 Benatzky eventually started work on the new operetta Marton had signed him up for, originally called, like the stage play, Margarete von Navarra, a parody on the French establishment in the 1840s, depicting politics as a frivolous society game for the rich and bored. Later the title was changed to Der König mit dem Regenschirm, “The King with the umbrella”, referring to the French monarch Louis-Philippe (1773-1850), who, it is said, used to dress up as a civilian and go jovially walking among his subjects, pretending to be one of them.

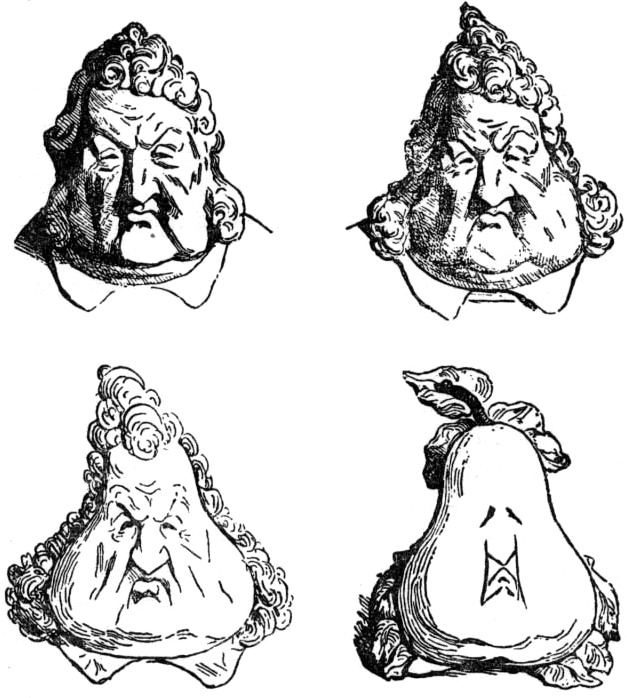

The famous 1831 caricature of Louis Philippe turning into a pear would mirror the deterioration of his popularity. (Honoré Daumier, after Charles Philipon, who was jailed for the original.)

However, the caricatures of Honoré Daumier famously ridiculed the king, showing the seemingly harmless monarch as a corrupt ruler, removed from the throne by the 1848 revolution, which brought on the glamorous Second Empire and Napoleon III instead.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter portrait of King Louis Philippe.

In Benatzky’s operetta, Louis-Philippe only appears once, singing a purposefully silly song (“Ich geh’ zum Beispiel gern spazieren”, i.e. “I, for example, love to go walking”). The main action deals with the farcical ex-minister Morelli who speaks in an idiotic Italian-French accent (“Una, due, tre…”) and who instructs Count Percy d’Avencourt in the ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of politics. Percy, freshly appointed as prime minister, is also freshly married to Suzanne. She is proud of her husband’s unexpected political career, to the helpful extent of giving him the political program that makes him universally popular – Margarete of Navarre’s manifesto: “people should stay at home and have babies, eat and be happy” – but she is less delighted with the fact, that her ever more powerful husband is never at home and never in her bed. So she plots to overthrow the government – and get her man back. A faint echo of Aristophanes’ feminist anti-war comedy Lysistrata, 411 BC.

The show was originally produced in April 1935, to great critical acclaim, in Vienna at the Theater in der Josefstadt by director Otto Preminger (1905-1986), who would soon leave Austria and embark on a major Hollywood-career (directing Carmen Jones, The Man with the Golden Arm, Porgy and Bess, Bonjour tristesse, Anatomy of a Murder).

The actor Oskar Karlweis, as seen on an autograph postcard from 1935.

A local newspaper remarked after the opening night: “Just as the dark tragic theater form of Naturalism blossomed at the turn of the century, in times of peace, now, in times of great uncertainty, audiences like to see nothing more than stories set in a time which one did not have to endure and overcome, but in which one enjoyed oneself and had fun. King Louis Philippe, who promised the French a good and contented life, and reigned with a radical, but loveable philosophy of general happiness, seems to be the ideal character for a show today.” Preminger’s production set the action in a giant music box that kept turning, from scene to scene, making the operetta obviously anti-realistic and world politics (and revolutions) nothing more than a ‘Muppet show’. In Preminger’s production, the singers were added as figurines in a slapstick comedy filled with bouncy Rumbas, Foxtrotts, Slow Waltzes and Can Cans. The leads were taken by two Jewish cinema and theater superstars of the time: Oskar Karlweis (1894-1956), of Drei von der Tankstelle-fame, as Percy, an experienced Benatzky interpreter with an unmistakable squeaky voice and much personal charm, and fat bellied Otto Wallburg (1889-1944), who had been Benatzky’s original Giesecke in White Horse Inn and one of the leads in Der Kongress tanzt, as Morelli.

Much of the show’s initial success rested on the comic timing and zany humor of these two artists. Other parts were taken by saucy operetta diva Rita Georg (1900-1973); Benatzky himself sat in the pit and played the piano, together with a small scale orchestra of 12 musicians.

The papers called König mit dem Regenschirm “the prettiest, most charming and wittiest work Benatzky wrote so far” and labeled the performance “extraordinary.” It settled in for a long run in Vienna and was an artistic and commercial success.

However, once all of the above mentioned artists left Austria for the US, or (like Wallburg) had been deported to concentration camps, the show was largely forgotten. Still, the Nazis kept putting on Benatzky titles even after their creator had departed for the United States too. There were too few ‘Arian’ composers around that they could play, so Benatzky was – together with Franz Lehár and Eduard Künneke – their first choice among the living, internationally acclaimed operetta composers. Especially the ‘chamber’ works were performed, for which Benatzky had also written the lyrics, which made them ideally suited to the Nazi’s racial ideology, since no Jewish librettists were involved, as in Lehár’s case. (Even if Benatzky, like Lehár and Künneke, was married to a Jewish women, a fact the Third Reich cared to mostly ignore.) It’s not surprising, under these circumstances, that Viennese publishing house Doblinger issued a “new version” of König mit dem Regenschirm in 1939/40 for the German market, with toned down political jokes.

But this new version never caused the stir and hype of the original production.

It is amazing that of all the operettas on offer after 1945, including the formerly forbidden ‘degenerate’ (“Entartete Musik”) pieces by Jewish composers, the Berlin radio station RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) should have chosen to produce the political satire König mit dem Regenschirm in 1948, only three years after the end of the war and one year before the founding of the German Democratic Republic.

The logo of “RIAS” in neon signs.

But it seems that in those turbulent times of a Germany in ruins, the Nuremberg trials taking place, and the political future highly uncertain, a show about a woman who wants her man to turn his back on politics and return to home, bed and a family life was just as topical as it had been, for different reasons, in 1935.

The young actor Erik Ode in uniform.

Though the star-studded RIAS production was recorded only 13 years after the Viennese world premiere, the style of performance could not be more different. The score was rearranged in the new ‘swing fashion’ of the era by Austrian conductor Alfred Strasser (who later wrote the music for German film classics like Grün ist die Heide and Das Spukschloß im Spessart), the musical clock idea and the associated mechanic music (functioning like a leitmotiv in Benatzky’s original concept) was erased from the score, and instead of the irresistible Jewish burlesque style of Karlweis and Wallburg, a more harmless, less edgy style of operetta performance, typical of the Nazi era, was adopted by the lead singers: later legendary TV-detective Erik Ode (1910-1983)as Percy, giving a laid back rendition of the hit song “Mal geht man links, mal geht man rechts” (“Sometimes you walk left, sometimes right”), cabaret star of the RIAS radio program Die Insulaner, Joe Furtner (1893-1965) as Morelli and film-diva Winnie Markus (1921-2002) as a sweet voiced, but resolute Suzanne (photo left).

Winnie Markus as an operetta heroine.

Whatever the stylistic drawbacks, the performance is fascinating. It is one of the few surviving operetta recordings from that little-known and little-documented era, and it is also the only existing full recording of this now largely forgotten Benatzky masterwork. It certainly deserves a revival – perhaps more in the farcical style of 1935 than the over-sweet and over-chaste approach of 1948? Still, as a reminder of post-war operetta history in Germany this RIAS-version – issued on CD for the first time ever – is priceless. It also refrains from the later, unfortunate operetta ideal of casting shows with opera singers who over-sing and under-act the music. Here, we hear typical character voices who adapt well to the requirements of Benatzky’s stylish score, even if they miss most of the obligatory irony and parody. Maybe the over-the-top grotesque humor of ‘Jewish’ German-language operetta from before 1933/38 can be revived in the new millennium?

Fascinating article. Will try to seek out CD.