Dániel Molnár

Operetta Research Center

28 August, 2019

Operetta appears more and more frequently in scientific discourse, but what about revues and variety shows? It’s a new field for theatre historians to discover, and one day perhaps it will also have its own research center. I would like to share a couple of results and interesting facts from my newly published book about shows during Hungarian Stalinism without going into deeper scientific analysis. (That’s in the book.)

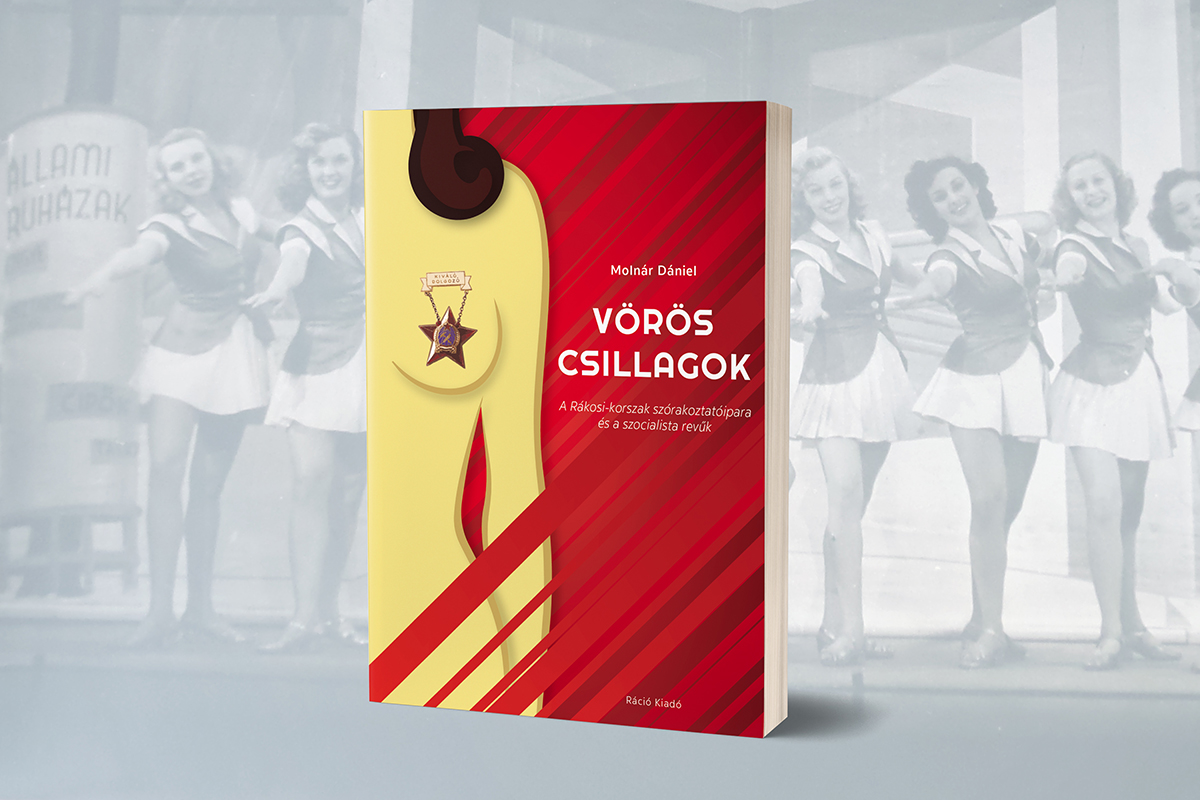

Daniel Molnár’s book and a line of ’State Department store girls’ in the background. (Photo: Collection of Béla Karády)

There are three important factors which made this research possible. (1) Due to the nationalization of theatres in 1949, almost their complete documentation survives in state and local archives. (2) The kind help of 19 private collectors of theatre documents and memorabilia from all over Europe, who shared their knowledge and collection with me. Without their help this study would have resulted different (= mostly false) deductions. I have to thank particularly the four main former collaborators (already in their 90s) who decided to leave their story with me soon before they died. (3) A PhD-student grant from Atelier – French Hungarian Department of Historiography and Social Sciences (University Eötvös Loránd Budapest) which helped me to have regular meals during the first three years of the research.

The analytic history of revues and variety shows in Hungary was a blank canvas, so I approached post-war shows from two main different points of view. First, focusing on the changes in legal regulations, as well as the institutional changes of the field comparing to its pre-war state. A new municipality-owned central management, called FŐNI (abbreviation for ’Municipal Institutions of People’s Entertainment’) was founded, managing two open air stages, the largest theatre hall of the city, a revue theatre, a chamber music-hall, the Municipal Grand Circus, and other small family businesses in Városliget (City Park). This institutional reorganization can be described simply as the last phase of transforming Hungarian theatre structure; however, it was more than that: a group of ambitious twentysomethings’ rise to control a significant, but less prestigious part of Hungarian theatre.

In 1948, co-working with Margit Gáspár (a communist intellectual, who soon took over the Operetta Theatre with govermental approval) a group of young cadres – also a close circle of friends – Béla Karády, János Kublin, András Sólyom planned to take over the remaining private elements of theatre industry. Research showed that the new institution was in fact not created based on instructions of the Party, nor copying a Soviet example (as it was obligatory in almost every field); but rather the personal interests of the aforementioned group. Their personal relationships, political connections and the low prestige of entertainment made this possible: it fell quite far from the main political-personal battles and interests of esteemed theatre professionals.

Lilliputian (midget) revue singing about industrial productivity. (Photo: Ernő Márton Kovács, fortepan.hu)

We Attempt To Fill This Genre With Socialist Meaning By Taking Out Its Bourgeois Motifs

The second aspect was the analysis of actual productions – alongside with the practices of how a production was created from an idea to opening night under strict governmental control – contrasting the process with the 1952 Folies Bergère show Une Vraie Folie. The structure of Hungarian shows changed radically: they became plot-driven and so they rather resembled operettas and musical comedies of the time. (Genre flexibility seemingly allowed to change the emphasis of show effects, but from season 1950/51 the productions started to follow a single dramaturgical pattern.) The reason behind this was the rhetorically rejected, but still existing cultural distinction that valued drama-based productions higher than other ones. The appearance of traditional role types radically decreased and socialist-realist role types were introduced with direct or indirect political messages. Apart from the classic communist stock characters, completely new role types appeared in the shows, like the ‘astonished countryman’ which was frequently used to present the new ’wonders’ and old sights of the city. The villains’ personality (either intriguing or comic) corresponded with the political imagery of determined ‘enemies of the state’. The hero’s sidekick type usually gives up his ‘old-fashioned’ thoughts and behaviours by the end of the show, and joins the new society. Star roles remained (as well as the related dramaturgical and staging patterns to his/her entry and leave), but their significance were considerably reduced comparing to the ‘progressive hero’ and ‘progressive heroine’ types.

“Go slowly, you get farther!” Almost every scene had to have educational/propagandistic content. (Photo: National Széchényi Library – Department of Theatre History)

Traditional revue show themes were discarded or reinterpreted in communist context. Most of these themes (Budapest as a metropolis, exotics, self-reflection, history/nostalgia, attractions, love) could persist, but parodies of other entertainment products (e. g. current hit shows, operettas) and references to nightlife or even to evenings themselves were discarded. Jazz, as a popular music genre, was ‘preserved through banning’ since it still could have appeared on stage but exclusively in negative context. Eroticism on stage was restricted, and soon almost completely disappeared – its maximum was a kiss between the working class lovers under the Stalin Bridge in the finale.

Moroccoan fair-scene, 1949. Note how most of the dancer’s body are covered almost completely; however the line of their breasts are marked by the decoration. (Photo: Collection of Béla Karády)

The designer’s possibilities were narrowed by naturalistic obligations and the increased role of the writers: in some cases, scenes were already imagined and defined in textual form. In the tenth show, Most jelent meg (The latest issue) the journalists visit a factory:

Scene 19. An iron foundry. A huge bowl flies in slowly from the left with dignity, in front of the furnace on the right. The old Miska, Kőrösi, Éva, and the reporter are standing on the right side of the furnace.On the left a Worker holding a tapping rod in his hand. When a couple of seconds later Miska and Kőrösi sets the bowl under the mouth of the tapping, he [?] smashes the clay furnace lining in the throat of the furnace and the melting white iron river bursts through the tapping. Kőrösi stands touched and watches their reflections in the river of fire bursting from the furnace.

Unfortunately we do not have any iconographical sources for this scene. For better understanding I recommend watching the Casting an iron episode of British Instructional Films. This was the result of a writer’s and not a designer’s fantasy: it is quite difficult to turn narrative elements like „watching their reflections in the river of fire” into a stage spectacular; but it corresponded to the state propaganda developing the heavy industry. The designer’s task was only execution: how can one create such effect (with the lack of proper stage infrastructure) to fulfil naturalistic requirements? The designer must have got himself familiar with the process and techniques of actual iron casting to understand the description; and then find a way to stylize it as much as possible for the stage, still to be accepted as ’naturalistic’. Set structures, such as vertically organised scenes, mass scenes, and the decorational use of the human body were also discarded in the name of naturalism.

A very rare shot: The stage crew posing in a revue set. Municipal Comedy Theatre, 1952. (Photo: National Széchényi Library – Department of Theatre History)

Mission: Impossible

The attempts to create a socialist revue and to legitimize revues and variety shows for the stalinist state (like operetta) were unsuccessful. Even though they enjoyed a financial and political support and even ticket prices were cheap. If there were not a political intention to terminate the experiments (as it was for starting them), stage revues could theoretically survive this period. In the state-party structure the maintenance and support meant high expectations on administrative and production levels that the new managers and creators could not meet. To the participants of these experiments it was clear from the beginning that this complex popular entertaining genre cannot be reformed, since it was impossible to please the audience and fulfil political requirements at the same time. It is likely that these futile revue experiments significantly contributed to the fact that today Budapest does not have a representative revue theatre, like the Moulin Rouge in Paris or the Friedrichstadt-Palast in Berlin. Because of this failure, in the following years revues were mostly restricted to small stages and nightclubs – which made it much harder to compete with the new forms of entertainment.

“Live! Live longer! Even longer!” (Photos: Lajos Karasz – Ákos László Visky / National Széchényi Library)

The Theatre History Department of the National Széchényi Library decided to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the nationalization of Hungarian theatres. Based upon my book, I curated an exhibition of the same title which is also a sequel to my previous exhibition ’The Unknown Girl’ about Budapest nightclubs and entertainment in the 1930s. Although I had to deal with a space which is hardly suitable for an exhibition (and the infrastructure also had its issues) with the extraordinary enthusiasm of my colleagues helped me to make it a headline on the main Hungarian news site, index.hu. Since these productions were overlayed by government propaganda, my concept was that the visitor has to make an effort (like opening a drawer, pulling a curtain etc.) to actually see the exhibited iconographic and other show memorabilia. Besides being functional, I tried to use the given space symbolically. The one discovered collaborator of the state security in theatre business (the rest we still don’t know due to political restrictions of the folders) is in a huge catalogue drawer to give you the impression what could be beyond; or the politically denied actresses who were banned from stage are just dropped to the floor, ’excluded’ from the exhibition. (Visitors regularly attempt to pick it up their pictures and place them somewhere, but the cord is intentionally short to do so.) Due to its success it was prolonged until 12 October 2019, ending with a finissage and guided tours by me with selected gossips from the 1950s.

Red Stars: Entertainment Business in the Rákosi-Era and the Socialist Revues; Ráció Publishing, 2019 p. 494. with 129 pictures. (In Hungarian with English summary)