Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

29 August, 2019

When Germany’s ultra-conservative Offenbach crusader Peter Hawig – who in a recent Jacques Offenbach Society newsletter remarked that “tying” the composer to anything explicitly sexual is “unappetizing” – writes about courtesan Cora Pearl and (!) the million dollar mermaid Esther Williams in the booklet for this latest Offenbach CD, you might want take a deep breath. And wonder: what is going on? The CD in question presents ballet music for the revised Orphée aux enfers version of 1874, with the world premiere recording of the later added aquatic ballet Le Royaume de Neptune, i.e. in the kingdom on Neptune, Offenbach’s very own version of Aquaman. (Yes, move over Jason Momoa and Nicole Kidman.)

The cpo cover for an album of Offenbach’s ballet music wrwitten for the 1874 version of “Orphée aux enfers.” (Photo: cpo)

As you probably know, Offenbach expanded his small scale 1858 Orphée for the Théâtre de la Gaîte into an “opéra-bouffe-féerie” of four acts and 12 scenes. The supersizing of the originally rather intimate show meant that a lot of dancing was added. This glorious extra music has been included in various recent performances, at least partially. It’s in the Marc Minkowski Orphée from Lyon, it’s also in the latest Orphée from the Salzburg Festival. The most expansive recording of the 1874 version is by Michel Plasson on EMI, there’s also an album on Philips with Antonio de Almeida conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra, it includes most of this ballet music and the newly composed overture. Plasson only recorded the rousing second part of it, de Almeida the entire thing. (I admit the shortened Plasson version is a much more effective opening; for me at least; it knocks you right in the face with its fanfare.)

The EMI recording of “Orphée aux enfers” conducted by Michel Plasson. (Photo: EMI)

So here you have all of this ballet music, again. Not quite as quirky as Mr. Plasson plays it, often a little slower and with more gravitas, performed by conductor Howard Griffiths and the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (DSO). The must-have item on this new album, however, is music that was only recently discovered, composed by Offenbach as a later extra alteration of the 1874 version.

In the “original” 1874 score the third act (in Eurydice’s boudoir) ends with a ballet of golden flies who are summoned by Cupid to find Eurydice. You’ll recall that she’s gone missing to run off with Jupiter. At the end of the ballet, Pluto as the God of the Underworld flies off into the air himself – it’s one of those jaw-dropping moments that opéras-féeries were famous for, a century before Marvel Studios or Roland Emmerich made such effects their trade mark.

Since this new Orphée was a success, it ran for quite some time. And it seems that Offenbach needed some novel attraction to draw in crowds in the summer of 1874. As an antidote to the heat, he conceived an water ballet as substitute for the dancing golden flies. This water ballet is entitled L’Atlantide or Le Royaume de Neptune, consisting of eleven (!) extra scenes.

In this underwater spectacular, Eurydice can be seen on the shores of the mythical island Atlantis. The tide begins to rise and water consumes the entire stage. We’re swept away to a sea world where lobsters and crabs dance (à la Disney’s Little Mermaid), where children are costumed as toads etc. In this wet-and-wild paradise scenes of jealousy are being played out (between the crabs), before Aphrodite awakes and takes us to the lost world of Atlantis itself – with trumpeters, amazons, Argonauts. And let’s not forget Eurydice!

The 32 minute (!) ballet ends with the birth of a pearl, then this entire magical world sinks back into the deep ocean – a hidden treasure island, in which Neptune rules triumphant.

This ballet was recently discovered by Jean-Christophe Keck in a loft, he claims. It was edited, and published by Boosey & Hawkes, it was then given a first concert performance in Vienna. After that, DSO recorded it in Berlin, in March 2019. Now, hardly five months later, there is this CD, released by cpo.

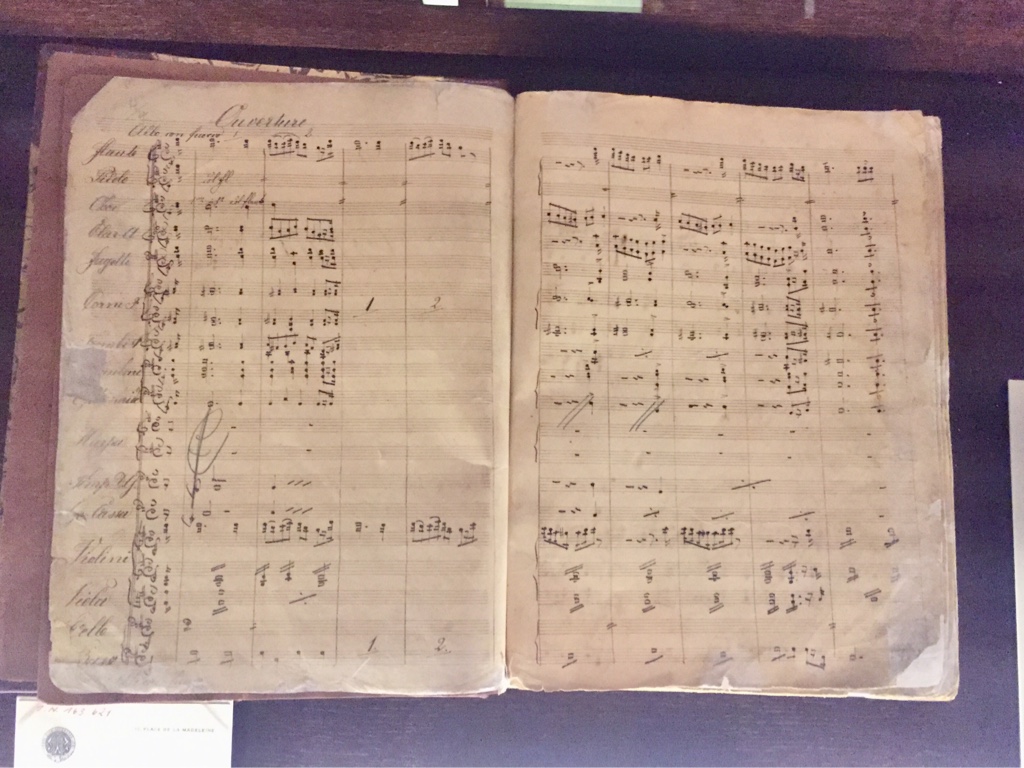

The CD closes – after the Ballet Pastoral and the Divertissement des sognes et des heures – with the better-known Carl Binder version of the Orpheus in der Unterwelt overture, written for the first Viennese production. That score was recently bought by the Vienna Stadt- und Landesbibliothek and included in their Offenbach/Suppé exhibition.

The full score for “Orpheus in der Unterwelt” arranged/orchestrated by Carl Binder in 1860 for a Carl-Theater production in Vienna. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

The music throughout is beautifully played by DSO, even though a bit on the grand side, not in a tongue-in-cheek version; but it’s a treat I enjoyed very much.

If you wonder how Cora Pearl fits into all of this, the answer is: she was Cupid in the 1867 revival (without extra ballet music). The fact that Mr. Hawig mentions her, and Miss Williams, documents a new way of thinking outside-the-box in German musicological circles. And maybe it also documents a new awareness of pop culture, in the wider sense of the world.

Famed courtesan Cora Pearl as Cupid in the “Orphée” revival, Paris 1867.

In the aforementioned newsletter of the Jacques Offenbach Society, Laurence Senelick writes about this summer’s symposium in Cologne and Paris, at which Mr. Hawig was obviously present, and states about two of his disciples: “There were stimulating papers on dance and reception history, but musicological pedantry was also on display, with papers painstakingly analyzing scores note by note and using terms too technical even for this audience of specialists.”

A different kind of musicological “pedantry” is evident in this cpo booklet, because Mr. Hawig takes great pains to explain that Offenbach’s operettas are not really “operettas” – a term we “mostly associate with the more sentimental Viennese shows of the 20th century,” he writes. But Orpheus and many other shows were labeled “operetta” in Vienna, Berlin, and elsewhere, so we might ask if the sentimental notion of the genre – as also promoted by Richard Traubner in his Operetta: A Theatrical History – might not need revision. (I think it does; and that would benefit Offenbach and many 20th century operettas.)

One way or another, this CD is a most welcome summer treat. Not just because Neptune’s ballet is filled with amazing music which Offenbach partly took from earlier sources (e.g. the Décameron dramatique, and Le Papillon). Some of the newly written music was later recycled by Offenbach in Le Voyage dans la lune, including the famous tune that was utilized for the Mirror Aria in Tales of Hoffmann; it pops up here unexpectedly and is as beautiful as always, even or especially in an underwater context.

It would be great if DSO and its new chief conductor Robin Ticciati could embark on a more expansive Offenbach voyage in the future and present more Offenbach music. The playing of the orchestra is wonderful. And there are still so many Offenbach shows that are not available in modern recordings, among them Genevieve de Brabant et al.

By the way, when Erik Charell produced his Im weißen Rössl in Berlin in 1930 he also included a notorious aquatic ballet, showing his hand-picked dancers in bathing suits jumping into the Wolfgangssee and emerging dripping wet. The Nazis and other conservative groups were appalled by this display of almost naked bodies in an Alpine setting. It ruined their idea of “German” culture. And they took Rössl out of circulation almost immediately in 1933. I’m sure the scandalous potential of such a bathing setting was not lost on Offenbach and a prime reason for him to take his audience on an underwater journey.

Jason Momoa as “Aquaman” in the 2018 movie version. (Photo: Warner Bros. Pictures)

As the 2018 hit movie Aquaman demonstrates, our fascination with underwater worlds à la Le Royaume de Neptune has not stopped, and dripping wet stars can still draw in crowds, not just during the height of summer.

For more information, click here.

how in the world is Aquaman the first thing to pop in your head when contemplating an underwater ballet by Offenbach?

In this context Busby Berkeley is the logical train of thought. But who nowadays remembers the production number By a waterfall from Footlight Parade (1933), or even more fitting- the Birth of Venus sequence in Spin a little web of dreams in Fashions of 1934? Esther Williams is, being an MGM Star, just the last still known female non singing musical stars of the pre 1950s.

The aquatic (and aerial) ballet had been a feature of the Parisian opéra-bouffe féerie for a long, long time before ORPHÉE. Check out, for example, BABIL AND BIJOU.