Dario Salvi

Cambridge Scholars Publishing

27 September, 2017

New operas are hard to come by these days—at least that is what I have always been told. Finding an opera house or an opera company willing to take a chance in producing a new title or reviving an old work is said to be almost impossible. Everywhere you go the operas belonging to the standard canon are performed. You could travel the world for a year and see a different production of one of these standard operas every day. But how many operettas could you find and where?

Cover for Richard Genée’s “The Royal Middy/Der Seekadett,” edited by Dario Salvi. (Cambridge Scholars Publishing)

Well, if you are lucky enough to live in Central Europe you might bump into some productions of works by Millocker, Suppè, Johann Strauss Jr., Oscar Straus, Kalman, Lehàr and a few others. If you are in the United Kingdom you are more or less limited to the works by Gilbert & Sullivan. Elsewhere Die Fledermaus and the Merry Widow are the queens of operetta, with Offenbach as king; but if you are lucky you might bump into The Dollar Princess in Philadelphia, Countess Maritza in Sicily or even Die Afrikareise in Norfolk, UK.

Conductor Dario Salvi and his Imperial Vienna Orchestra.

On a lighter note, there definetly is a revival for operetta. We have to thank all the operetta lovers out there that spend their time and money to try and bring back this often neglected art form. As for me, I want to be a driving force in this revival. I want to show that we cannot afford to let this music and poetry be forgotten any longer. The work of reviving an old musical masterpiece surely is gigantic.

One must think about finding all the music, the conductor’s score, vocal scores for the singers and choir, promptbooks and scripts, stage directions, costume plot, scenery etc.—and most of the time without knowing if the final result will be worth all of that energy, time and money. In my experience, it certainly always is.

Pasha Fanfani (center) with Bedouins, on the poster for the 1884 production of “A Trip to Africa” at Haverly’s Theatre, Broad Street, Philadelphia. (Photo: Dario Salvi Collection)

I have had the pleasure of restoring, researching and reviving more works in the last two years than I could have possibly predicted. It all started with Suppè’s comic opera Die Afrikareise (A Trip to Africa). Years of research and hard work paid off. The music is exciting, beautiful, and Viennese with a subtle nudge to the Arab world. The plot is layered, exotic, sensual and over the top—which is, after all, part of the draw of operetta. Performing the work on stage with a chorus, singers and an orchestra was the climax of it all, and having been able to record it and save it for future generations was a sheer pleasure. The moment I closed the last chord of the Finale I was hooked for life. I had to bring back more and more of this amazing music and these impossible plots. (For a review of the recording, click here.)

Composer and librettist Richard Genée.

Suppè and Genèe were my first loves in the world of operetta—the former for his music, the latter for his stories. When I discovered that Genèe was also a composer of note (and notes) I wanted to find out more about him. While working on other projects (Meyerbeer’s Romilda e Costanza and Brandenburger Tor, Suppè’s Mozart, Rumshinsky’s The Broken Violin and Genèe’s Freund Felix) I found my attention often shifting to two recordings by the Hamburger Rundfunkorchester of two of Genèe’s Operas, Nanon and Der Seekadett. I was already familiar with the music from Nanon, having conducted Anna’s Song, the Quartett and the Overture (after having restored it from the manuscript) in concerts before.

I did not know anything about Der Seekadett, but I liked what I heard. Sadly, these recordings are only excerpts from the operas at only 25 minutes long, and heavily arranged as medleys of songs. I wanted to find out more about what was not there. Luckily enough I found some selections, quadrilles, marches and vocal numbers in the Library of Congress (USA) and even Eduard Strauss composed (or compiled) a quadrille on melodies from Der Seekadett.

Before deciding if I really wanted to dedicate all this time into working on Der Seekadett I had to know more. I concentrated on the libretto, by F. Zell (aka Camillo Welzel) but I could not find it anywhere. Giving up is not part of my nature and so after a month of thorough research I managed to obtain everything I needed. I sourced the English libretto from the American version of the opera, called The Royal Middy (please look at the Historical Reviews and Performances section of the book to find out more about why this name was adopted) as well as the Italian libretto of Lo Scacchiere della Regina (The Queen’s Chessboard), as it was known in Italy. I loved what I read and heard in the recording and wanted to rescue the work.

Isabelle Everson als “The Royal Middy.” (Photo: Archive Dario Salvi)

Through this work of passion, I discovered why the opera had a lifespan of 68 years. The plot is quite simple, easy to follow, full of funny lines and great moments (including a duel between a navy officer and our hero, Fanchette, a lovely lady disguised as a Naval Cadet). It includes a cast of ladies dressed as cadets, children in the role of chess pieces, soldiers, sailors, politicians, monarchy, priests, a millionaire and an insubordinate slave—and if this wasn’t enough, the second act finishes with a human chess game.

Miss Ada Rehan as Donna Antonia in “The Royal Middy,” January 1880 at Daly’s Theatre. (Photo: Archive Dario Salvi)

Underneath all of this, the music is nothing short of sublime. Do not be fooled by the Hamburg recording—what you hear is a mutilated version of the opera, with shortened songs, questionable interpretations of tempi and a modified orchestration. Despite these drawbacks, it is a real pleasure to be able to listen to it, even in that form (there is a full bootleg recording from an Austrian 1994 production of the opera featuring Peter Thunhart as Dom Januario, which is sadly not commercially available). Great brass lines give us the pomp of the court, tambourines and castagnets give us the rhythm of a Brazilian bolero, there are waltzes, there are marches (we are after all in a Naval academy), and there are mellow melodies.

The music is never boring or stagnant, unlike many of the canonic operas. The attention of the listener is shifted constantly between arias, choral numbers, changes of rhythm and interesting harmonies. It surely is, in my opinion, a very good comic opera. There is no reason why Der Seekadett should not become part of the operatic (or operetta) canon.

At the time of writing, the orchestral score and parts are completed, the libretto, dialogues and all the material needed for a production is ready and a date is set for a concert performance at the Concert Operetta Theatre in Philadelphia in the autumn of 2017.

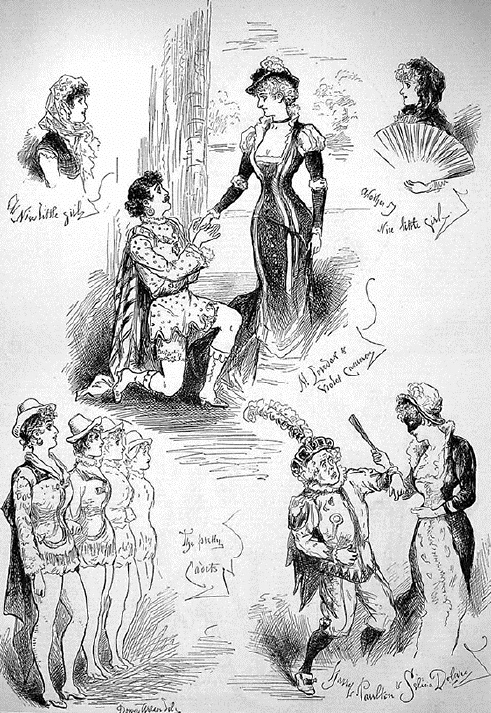

Scenes from “The Naval Cadets” from “The Illustrated and Dramatic News,” 17 April 1880, London. (Photo: Archive Dario Salvi)

While reading this book you will immerse yourself in a world populated by lovable and sometimes improbable characters, lovely poetry and interesting facts. Just a note of caution: the names of the characters change throughout the different versions and languages, for example Fanchette becomes Cerisette in England (in the highy criticised British adaptation called The Naval Cadets) and Norberto becomes Robert in Le Cadet de Marine in France and Lamberto in Lo Scacchiere della Regina in Italy—even though Lamberto is the name of another character in The Royal Middy.

Confused? That’s the beauty of it all!

Operetta researcher Dario Salvi exploring the ‘other’ side of the genre. (Photo: Private)

For more information, check the website of Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Are you able to supply the Genee CD.

Thank you

Andrew Hanley