Hans-Dieter Roser

Operetta Research Center

27 February, 2016

Vienna, 17 March 1883. At the legendary Theater an der Wien, Franz von Suppé’s latest show Die Afrikareise is given its world premiere. It is his 22nd operetta, at least that is what it says in an entry made by the composer himself in a handwritten list of his works; it can be found in the library of the City of Vienna (Wienbibliothek). It is his last listed complete work; later entries only mention unfinished projects.

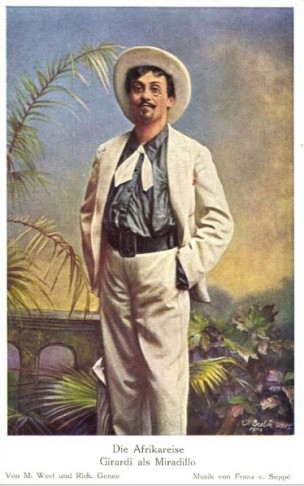

Star comedian Alexander Girardi in his “Afrikareise” costume.

With the premiere of Die Afrikareise, Suppé returns to the place where his career as an operetta composer had once begun. Twenty-three years earlier, his one-act Das Pensionat presented at the same theatre had been the start of a specific “Viennese” form of operetta, a new and separate sub-genre that established itself as an alternative to the successful Offenbach model previously imported from France. Several other composers had tried finding such a local formula for Viennese operettas, but it was Suppé who took the decisive step forward. The success of his amusing little piece about a boarding school for girls was so overwhelming that Viennese audiences showed more interest in Das Pensionat than in the latest compositions of the internationally more renowned Johann Strauss Jr., who had just returned from a concert tour to St. Petersburg in 1860.

In 1862, Suppé left the Theater an der Wien when it became clear that its director Alois Pokorny could not pay the salaries of his employees anymore. Suppé had both worked and lived at that famous theatre, in a room covered with skull-wallpaper, sleeping in a coffin, as is befitting for an eccentric star composer. He moved on to the provisional wooden – but very exclusive – Theatre on the Franz-Joseph-Kai, run by director Carl Treumann. When it burned down in 1863, the company moved onto the equally luxurious Carl-Theater in Praterstraße, where members of the imperial family, wealthy investors, the nouveau rich and the demi-monde met for nightly entertainment. The theatre was bombed in 1944 and pulled down in 1951.

The Carl-Theater in Vienna at the turn of the century.

While at the Carl-Theater, Suppé established himself as the most important composer of Viennese operettas. It was there that his three major full-length works were first seen: Fatinitza, Boccaccio,and Donna Juanita. All three became international successes, Boccaccio (based on the ‘scandalous’ The Decameron) probably being the single most successful Viennese operetta of the 19th century, globally speaking.

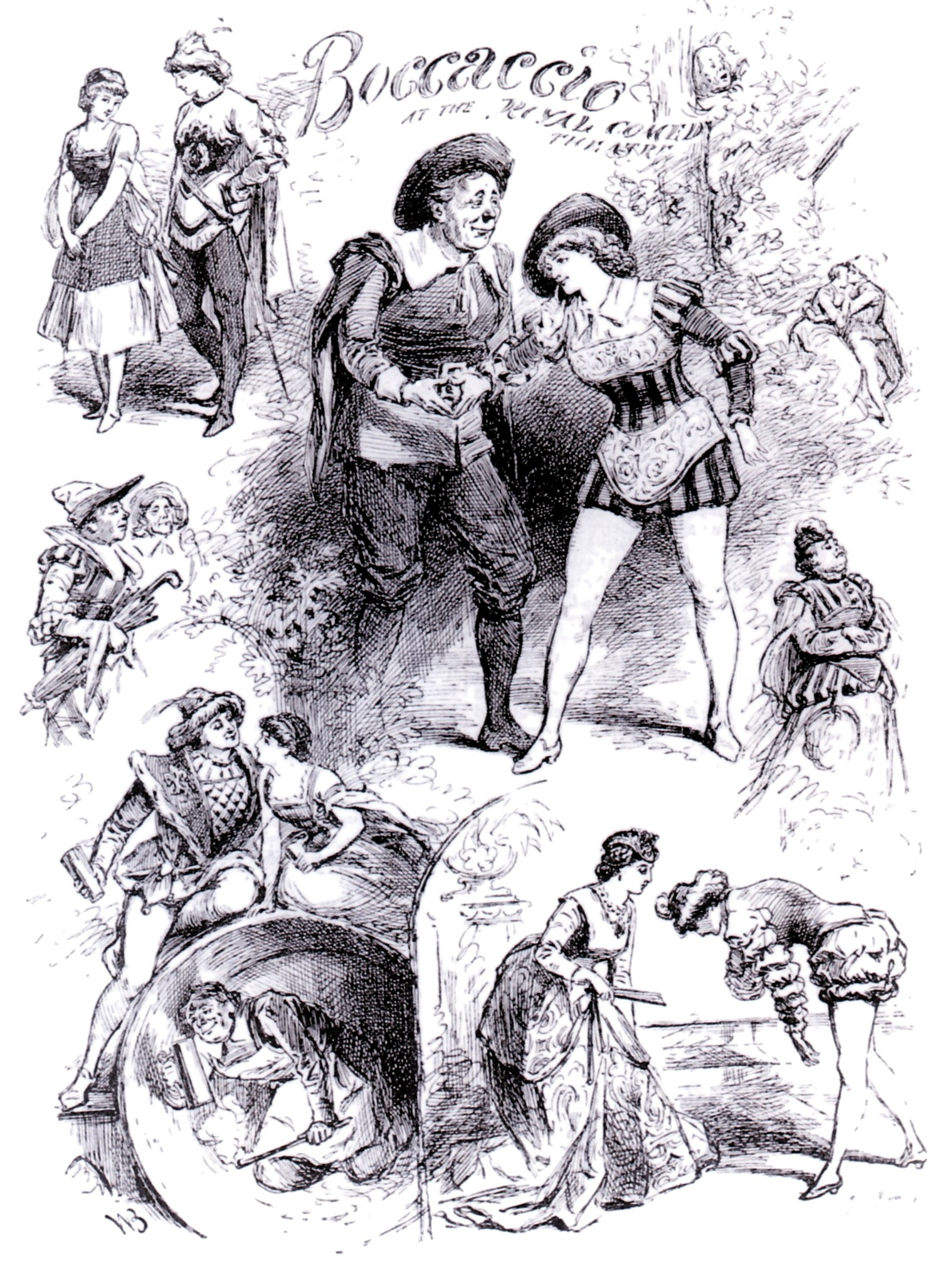

Poster for a “Boccaccio” production in London, 1882.

After his contract with the Carl-Theater ended in 1882, Suppé decided to return to the Theater an der Wien, where Johann Strauss Jr. had triumphed, in the meantime, with his own stage works, most notably with Die Fledermaus (1874). Suppé decided to premiere his next new show there, Die Afrikareise. There had been nasty rumours after his last show at the Carl-Theater, the operetta Herzblättchen, that Suppé had lost his creative drive and was burned out. This rumour was not entirely unfounded: the average life expectancy in Vienna in the 1880s was 60 years; at 63, Suppé was considered an old man who had nothing more to say to the world.

But his creative powers had not waned. In Herzblättchen, the confused libretto of Carl Albert Tetzlaff (a renowned director, but amateur librettist) had not inspired Suppé much. He did not even consider the work worthy of a proper overture; instead, he recycled the overture for his one-act operetta Das Corps der Rache, a show that had flopped 19 years earlier, closing after only 11 performances.

Suppé’s inspiration moved onto a totally different level with Die Afrikareise, mainly because the grand master of Viennese operetta librettos, Richard Genée, joined forces with him. Together with his long-term writing partner F. Zell he had paved the way for Suppé’s greatest previous operetta successes. But to regard Genée only as a librettist is not doing him justice; he was also a talented composer, esteemed even by Johann Strauss Jr. (with whom he wrote Die Fledermaus). Also, Genée was perceptive to the literary trends of his time and to the public’s expectations. For Die Afrikareise it was not F. Zell who collaborated with him, however, but Moritz West alias Dr. Moritz Nitzelberger. He was a friend from school and university colleague of composer Carl Zeller (Der Vogelhändler). He was also the director of the Moravian-Silesian Central Railways.

F. Zell had taught him how to write librettos in his spare time, so he could be part of the glittering and sexually liberated world of operetta in Vienna. It proved a perfect antidote to his more bureaucratic railway day-job.

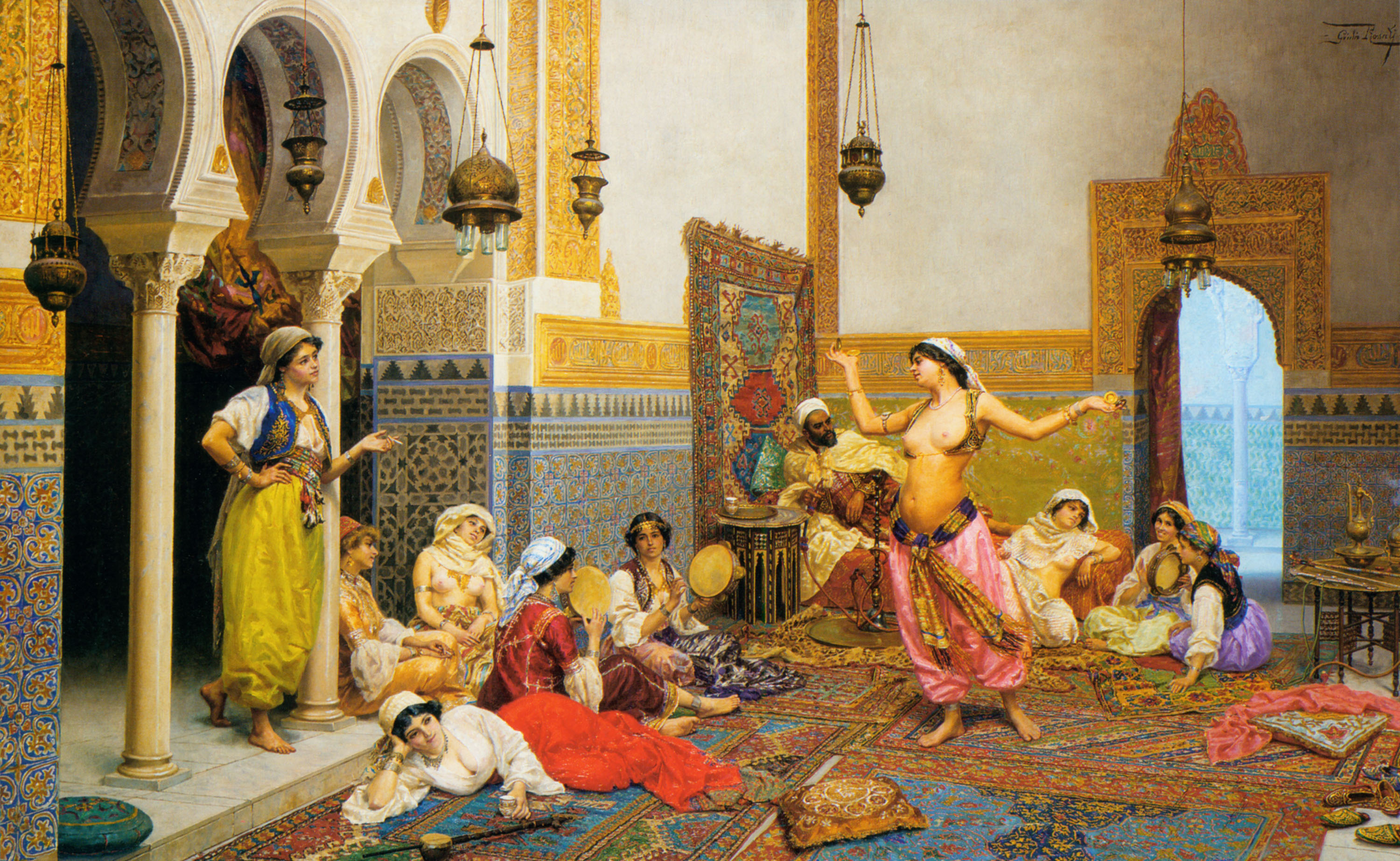

In sketching out the plot, Genée employed a well-tried strategy which he had invented for Viennese operettas. Whereas Offenbach’s Parisian works resorted to political parody and a radical send-up of the moral restrictions of bourgeoisie society, Viennese Operettas – within the confines of the strictly Catholic Habsburg regime – had to dispense with parody and a too-open criticism of Catholic moral values. Especially after 1880, Viennese operettas often replaced parody with sentimentality and added folk music elements. The formerly dominating erotic elements were now mostly restricted to cross-dressed female singers in trouser roles, showing off their legs, preferably in exotic places that stirred the imagination, such as Venice (carnival) or the Middle East (harems). The names of far-away cities and countries, known to the audience only through literature and newspaper reports, aroused feelings of longing for remote places and dreams of suppressed erotic longings.

The harem dance, oil on canvas, by Giulio Rosati.

The choice of locale for Die Afrikareise was: Cairo and surroundings. This was influenced by current political events, namely the occupation of Egypt by the English in 1882. It was a reaction to the nationalistic Urabi Revolt which opposed international financial control of the country, forced onto the Khedives. The revolt was put down by British troops under Field Marshall Garnet Joseph Wolseley. This political background is not mentioned in the libretto, but the topicality of the locale.

The music of “Die Afrikareise” never uses African rhythms or Egyptian sounds, like Verdi did in “Aida.”

It stays completely within the conventional spectre of Viennese operetta. Suppé never leaves the sound-world which he himself, as the founder of this particular sub-genre, had established. Whereas Strauss Jr., for example, was responsive to fresh musical influences, such as Richard Wagner, Suppé was not. Even though he had been present at the first Ring des Nibelungen in Bayreuth (1876) to hear his friend and former star Amalie Materna, who sang Brünnhilde. Maybe it was his hearing Wagner “pontificate” during the intervals that put him off? In his Afrikareise, you hear the triangle and tambourine as markers of exotism, for the rest, the half-nude female slaves happily dance the polka. Suppé also stayed faithful to his other compositional principles and ended the work with a rousing march in E-major. A successful instrumental version appeared under the title “Over Mountains and Valleys”.

Afrikareise introduced some interesting novelties. The libretto no longer moves the plot forward, step by step. Instead, the action develops erratically and jumps from situation to situation, as though to mirror the pace of modern life, almost like a 1920s Broadway revue. And just like in the jazz age, the new music is mixed with references to the classics, here, Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio is quoted.

The first performance of Afrikareise at the Theater an der Wien had an excellent cast: Karl Blasel, Therese Schäfer, Joseph Josephi, and Caroline Finaly. They were all stars from the highest firmament of Viennese operetta. The brightest star among them was Alexander Girardi in the role of Miradillo. The Wiener Zeitung wrote about him that he was “greater than the music, the text and everything else.” In short, he was a superstar. And he delivered a knock-out performance as a European conman (from Sicily), living in a hotel called “Pharaone” in Cairo and constantly on the run from his creditors.

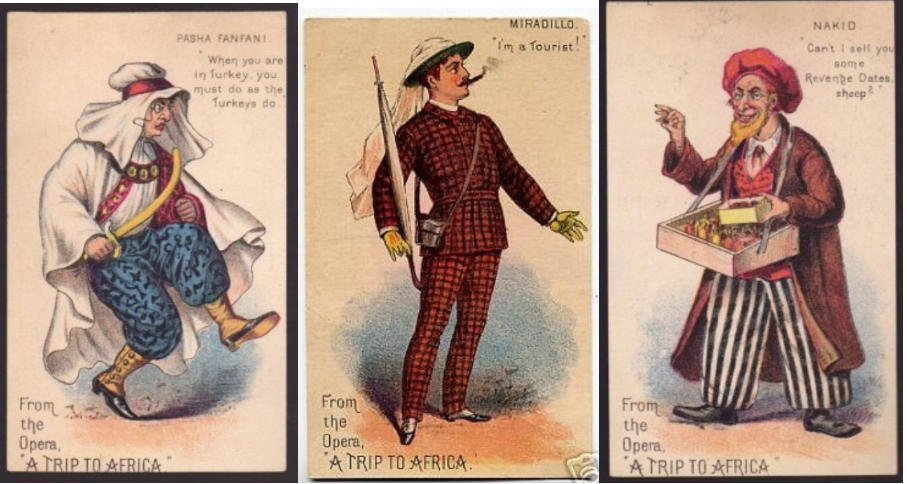

Suppé’s “Afrikareise” as seen in Boston, USA. (Photo: Dario Salvi Archive)

Even though the Vienna press was ambivalent in its evaluation of the new work, the audience loved the lavish show. The magazine Lyra praised it to the heavens, claiming Suppé had put all his rivals to shame with this, whilst the Wiener Zeitung accused the composer of being trivial, yet still acknowledging that the opening night was “an unheard-of success [ein unerhörter Erfolg]”, als “full on screaming and loud music that one feared going deaf.” These are two extreme opinions on an extreme work that quickly made its way to various theatres in Germany, large and small. In January 1884 Die Afrikareise was produced at Berlin’s famous Neues Friedrich Wilhelmstädtisches Theater, one of the notorious entertainment temples of the city where many Offenbach and Strauss operettas had been shown. One Berlin critic wrote: “The libretto does not offer much of a story that one could re-tell, but many colourful, very entertaining scenes.”

Many writers on Franz von Suppé had classified Die Afrikareise as one of his great works – in a line with Fatinitza, Boccaccio, and Donna Juanita – because of its many innovations pointing towards a more modern understanding of operetta, in the Busby Berkely and Erik Charell style. There was no London production, but the show went to the United States.

There was a production in 1884 at the Boston Bijou Theatre, with a printed English libretto for the American market.

Later, the show was somewhat forgotten because it did not fit the standard ideas of “traditional Vienna waltz operettas,” and could not be bent into that format which the more uninspired producers of operetta adhered to, especially after 1945.

Costume designs for the original Boston production of Suppé’s “Afrikareise.” (Photo: Dario Salvi Archive)

Perhaps our current times, with their more open minded understanding of the genre operetta, revue operetta, and the power of stage effects, is better suited to appreciate the unique charm of Die Afrikareise. Suppé’s inspired music more than deserves renewed attention. But so does the libretto that offers a colonial glance into an exotic world that we are today re-evaluating for our post-colonial sensibility.

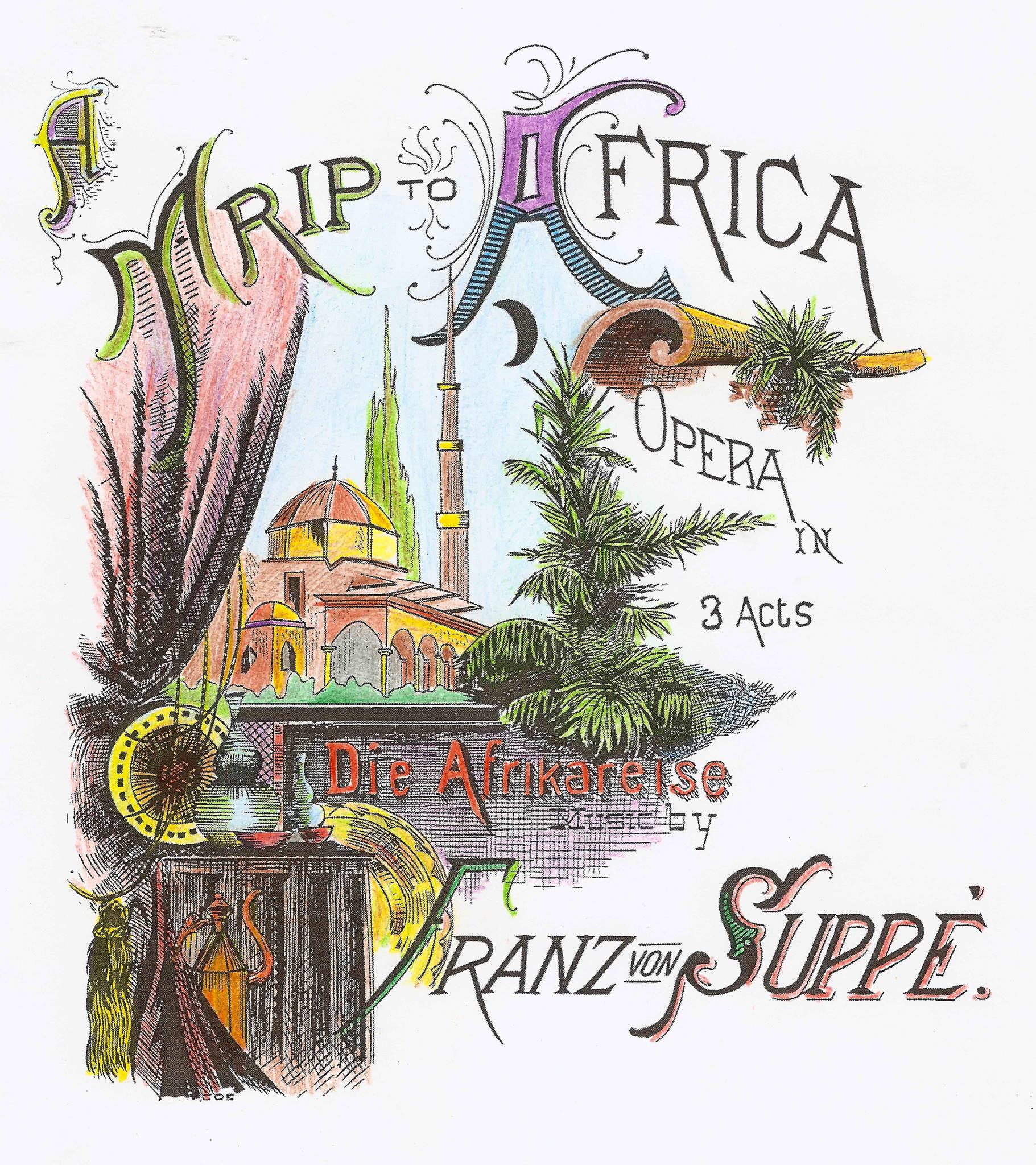

Sheet music cover for Suppé’s “Die Afrikareise.”

There is a scheduled concert performance on December 3, 2016, at the Maddermarket Theater, Norwich in England. It is a project of Dario Salvi and the Imperial Vienna Orchestra. For more information, click here.

I’ve long thought Suppe was underrated and the run of Boccacio at the Volksoper in the 70s and 80s was a gem in all aspects.

Kurt Ganzl tells me that the later production was a big let-down, however. They had almost stopped believing in it.

BOCCACCIO was the greatest Vienna operetta hit of them all, in the 19th century. FLEDERMAUS and all the other Strauss titles did not even come close. And for some reason Suppé got this image of being a “boring old fart” compared to the more “funky” Strauss Jr. But that’s not true. Any composer who sleeps in a coffin and has skulls on his wallpaper is not “boring.” Strangely, noone wants to rediscover Suppé as a truly modern and extravagant man, and play his operettas accordingly. Is it the long shadow of Nazi times? (After all, it’s due to films such as OPERETTE by Willi Forst that Suppé got this dusty image.)