Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

Although the Broadway musical theatre had established itself worldwide with its light-handed song-and-dance shows – Going Up, Irene, Mercenary Mary, No, No, Nanette, Sally and their kind – American producers had largely gone for imported shows or composers when the more musically substantial, romantic type of ‘operetta’ was required. Since the days of Victor Herbert and Mlle Modiste and Naughty Marietta, there had been few local successes in the operettic vein, but the enormous triumph of Blossom Time (Das Dreimäderlhaus) had shown postwar producers that there was a vast audience for a robustly sentimental show on classic light-opera lines, and they reacted accordingly. The show which gave the Broadway musical its first major international success of the kind was Rose Marie.

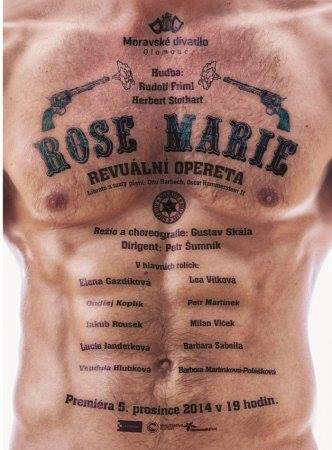

Poster for a Czech production of Friml’s “Rose Marie” in the new millennium.

Rose Marie was commissioned by Arthur Hammerstein from his nephew, Oscar II, and from Otto Harbach and composer Rudolf Friml with both of whom the younger Hammerstein had worked regularly since the pair’s first collaboration a dozen years earlier on The Firefly. The Firefly, built for an operatic diva, had been the last example of a memorable Broadway operetta, since which Harbach and Friml had concentrated on following the fashion for light comedy and dancing musicals, from the well-named High Jinks to the jaunty Blue Kitten of two seasons previously. Harbach and Hammerstein had also collaborated, under Arthur Hammerstein’s management, on three musicals: Herbert Stothart’s Tickle Me and Jimmie and the previous year’s colourfully Ruritalian Youmans/Stothart success Wildflower.

Using the producer’s suggested Canadian setting as a backdrop, the authors put together a plot which was, perhaps, rather more dramatic than was standard and which had a distinct air (and quite a bit of the plot) of Willard Mack’s 1917 play Tiger Rose to it.

That plot turned on a murder, the murder of a drunken villain by his mistress, and the use of that murder by the woman’s ex-lover to entrap his rival for the love of the show’s heroine. If the terms in which that tale was told here were less than precisely powerful, if the dramatic facts were rather drowned in romantic considerations and low comedy, and if the murderess in the case was also the entertainment’s principal dancer, the killing nevertheless remained as a dramatic spine for what producer Hammerstein referred to mouthfillingly as ‘an operatic musical play’.

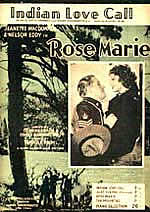

The first (silent) film version starring Joan Crawford.

Rose Marie la Flamme (Mary Ellis), the sister of a French Canadian trapper (Edward Cianelli), is in love with miner Jim Kenyon (Dennis King) rather than the well-off city man Edward Hawley (Frank Greene) whom her brother would have her wed. When Hawley’s half-caste ex-mistress Wanda (Pearl Regay) stabs her drunken Indian concubine (Arthur Ludwig) to death, Hawley engineers it that the suspicion falls on Kenyon, and the miner is forced to flee before the Mounties. Blackmailed by her brother, who agrees not to reveal Kenyon’s escape route if she will agree to marry Hawley, Rose Marie is gradually persuaded that Jim really is a killer, but Kenyon’s comical little friend Hard-Boiled Herman (William Kent) tricks the truth from Wanda. When the guilty girl realizes, rather late, that as a result of her actions she is going to lose Hawley to Rose Marie, she interrupts their wedding with her dramatic revelation. With the air now cleared, Rose Marie and Jim can finally get together. The comic element of the piece was provided by another triangle in which both Herman and the Mountie Captain Malone (Arthur Deagon) battled for the hand of soubrette Lady Jane (Dorothy Mackaye).

The music of Rose-Marie, and most particularly the romantic music, was one of the show’s principal assets. Rose Marie and Kenyon joined together in the Indian Love Call, a song which in later decades would become mocked – for its words rather than its melody – as the representative of old-fashioned musical theatre. The song had nothing of the old-fashioned or even the conventional about it in 1924 and it won an outstanding success as sung by King and Miss Ellis. King had a strong, lilting song (w Deagon) in praise of ‘Rose Marie’, Herbert Stothart combined with Friml on a ringing ensemble for ‘The Mounties’ and a pounding stage-Indian ballet (‘Totem Tom-Tom’) both of which backed up their spectacular set pieces with unusual strength, and, in contrast, Friml provided a delicately dancing melody for the heroine’s song about the ‘Pretty Things’ that money and Hawley can buy her, a piece which proved much more popular than the waltz ‘Door of my Dreams’ which the composer had thought would be the hit of the evening. Stothart was also responsible for some of the comic numbers, of which Herman’s profession of faith, ‘Hard-Boiled Herman’, stood up the best in front of the tidal wave of success that attended the lyric part of the score.

The “Indian Love Call” was one of the show’s greatest hits.

The producer extended his determination that the production was ‘operatic’ by announcing that he would not list the numbers separately in the programme (a determination echoed 60 years later by Andrew Lloyd Webber’s refusal to individually track his cast recordings) as they were part of the action. Of course, the comedy pieces in particular were nothing of the kind. The action surrounding them was as often as not there only to justify the songs and a piece such as ‘Totem Tom-Tom’ with its balletic murderess at its head was inserted solely as incidental spectacle. However, for anyone who cared, many of the numbers were indeed solidly linked to the characters or tale, just as they had been in musical theatre since the days of such ‘realistic’ musicals as Le Mariage aux lanternes and well before.

Hammerstein also posted up his serious intentions by his lead casting. Rose Marie was played not by an established star, from either the opera or musical stage, but by the young Mary Ellis who had played supporting rôles alongside Chaliapin and Caruso at the Metropolitan Opera at a very young age before quitting opera for the straight theatre. Rose Marie was her only musical rôle in America. Leading man King, like Miss Ellis, had abandoned a lyric career begun in Britain for Shakespeare on Broadway, but it was Miss Ellis who got the big billing, even if it were under the title.

The spectacular part of Rose Marie was also contributory to its success. Arthur Hammerstein’s Canadian settings as given shape by Gates and Morange were dazzling, the towering cliffs and mountains adding, Maid of the Mountains-style, both to the dramatic moments and to the long-distance moments of the romance, the `gowns and costumes’ of Charles Le Maire no less attractive and very numerous on the backs of the large company, whilst David Bennett’s arrangment of the dance of the massed ranks of Red Indian girls who featured in ‘Totem Tom-Tom’ was a show-stopper. If Hammerstein had operatic pretensions with Rose Marie, he certainly did not allow that to stop him taking out an insurance on success with a lavishly spectacular stage production.

Rose Marie was a huge hit on Broadway. One of the biggest of all time, even if, in cold figures, in the ultimate tot-up its run came to just 557 performances, a figure inferior to those chalked up by Irene and such old-time favourites as Erminie, Adonis or A Trip to Chinatown, but on a par with Florodora and Sally.

The first touring companies were on the road before the Broadway run was six months old. They were joined soon after by others, and these tours continued way beyond the end of the New York run. Alfred Butt took up the piece for London and produced it at the venerable Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which had been struggling along on a mixture of spectacular drama, pantomime and even films. Another young American performer, Edith Day (the original Broadway and London star of Irene), starred opposite patented tenor Derek Oldham and comedian Billy Merson and, once again, the piece found a huge following which resulted in an 851-performance, two-year run and the definitive re-orientation of the famous house to musical productions.

Poster for the 1928 film version with the young Joan Crawford in one of her first “Western” roles.

In Britain, as in America, the touring companies were on the road whilst the metropolitan production ran on, but London, unlike New York, also subsequently welcomed Rose Marie back on several occasions. Miss Day starred in a 1929 revival at Drury Lane (100 performances) and Raymond Newell played Kenyon at the Stoll Theatre in 1942, but a 1960 revival at the Victoria Palace done with neither the conviction nor the means of the original only reinforced the prejudices of those for whom such pieces were by then `old-fashioned’.

The show was produced by J C Williamson Ltd in Australia with Harriet Bennett (Rose Marie), Reginald Dandy (Jim) and Frederick Bentley (Herman) in the leading rôles, and once again it scored a major success through nine months in Sydney and a further six in Melbourne (Her Majesty’s Theatre 26 February 1927), but Rose Marie‘s longest run of all came, wholly surprisingly, in Paris. The Isola brothers who ran the Théâtre Mogador visited London and saw No, No, Nanette and Rose Marie. They bought both and staged Nanette first with such success that they were obliged, eventually, to cut short the show’s run in order to stage Rose-Marie (ad Roger Ferréol, Saint-Granier, and with a hyphen between the Rose and the Marie) within their option period. But this time the success was even greater, and by the time Rose-Marie closed, the production had created a Parisian long-run record with 1,250 consecutive performances.

Two young performers, Cloë Vidiane and Madeleine Massé, alternated in the title-rôle, the baritone Robert Burnier was Jim, Félix Oudart was Malone and the comic Boucot appeared as Herman whilst the world-travelling American dancer June Roberts led ‘Totem Tom-Tom’ (choreography credited to co-director J Kathryn Scott, so presumably not a copy of Mr Bennett’s).

The piece was luxuriantly staged, with the individually credited mountain scenes, the Totem Pole Hotel, a maison de couture (with a mannequin parade) and a Quebec ballroom commissioned from four different designers, decorated by hundreds of costumes, and the music played by an orchestra of 50.

There had been spectacular musical plays in Paris for decades and decades, but Rose-Marie set off a new fashion for opérette à grand spectacle which would last for many years until it ultimately destroyed itself and the musical theatre in Paris by its excesses.

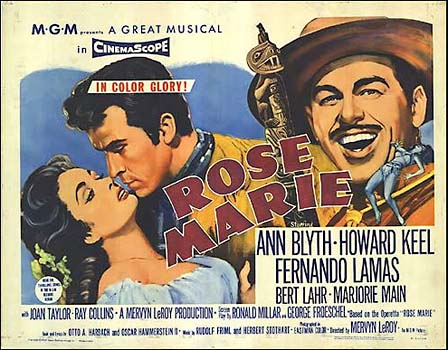

The film version starring Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy.

The Mogador brought back Rose-Marie in 1930 (20 January), 1939 (1 June), 1963 (23 November with Marcel Merkès and Paulette Merval) and in 1970 (19 December, starring Bernard Sinclair, Angelina Cristi), it was played at the Châtelet in 1940 (19 December with no less a Rose-Marie than Fanély Revoil) and 1944 (21 October, with Madeleine Vernon), at the Théâtre de l’Empire in 1947 and 1950 (12 May with Merval) and most recently at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin (18 February 1981) confirming itself as one of the staples of the musical theatre repertoire in France.

The show opened almost simultaneously with its Paris production both in Germany (ad Rideamus) where, in spite of Hammerstein’s personal supervision, operatic tenor Aagard Oestvig and soprano Margarethe Pfahl Wallerstein did not succeed in making the conventions of the Broadway operetta appeal, and in Hungary (ad Adorján Stella, Imre Harmath) where Irén Biller and Glenn Ellyn starred at Budapest’s Király Színház with rather more in the way of response. Prague also picked up on the show quickly (Urania Theater 18 June 1928) and the German version was introduced at the Brussels Stadttheater in 1933 (28 January).

The 1954 film version in Cinemascope.

In 1928 Rose Marie was also made into a film with Joan Crawford starred as a silent Rose-Marie (apparently with a hyphen!). If the tale without the songs was good enough in 1928, 1936 preferred it the other way round and the libretto was rewritten for a second MGM film in which Jeanette MacDonald, Nelson Eddy, Allan Jones and James Stewart participated. The score was also punctuated with bits of opera, ‘Dinah’, ‘Some of These Days’ and two extra Stothart songs. A third version, again rewritten, featured Ann Blyth, Howard Keel, Bert Lahr and Fernando Lamas and four additional songs dubiously credited to the aged Friml (who sat in an office at MGM and magically produced songs without a pen) as well as ‘The Mountie That Never Got His Man’.

The question of the hyphen in Rose(-)Marie has become a cause célèbre amongst those to whom such things matter. Stanley Green and Gerald Bordman, who must be considered the arbiters in such American matters of life and death, finally reached the compromise shortly before Stanley’s death that the stage show had no hyphen (except in France), whilst the film did. So why not.

UK: Theatre Royal, Drury Lane 20 March 1925; Australia: Her Majesty’s Theatre, Sydney 29 May 1926; France: Théâtre Mogador 9 April 1927; Germany: Admiralspalast 30 March 1928; Hungary: Király Színház 31 March 1928;

Films: MGM 1928 (silent), 1936 and 1954

Recordings: London cast recordings (WRC), selections (Columbia, Capitol, Decca, RCA, WRC etc), film soundtrack 1936 (Hollywood Soundstage), film soundtrack 1954 (MGM), French version (Pathé, CBS etc), Russian version (Melodiya) etc.

Do you have any pictures, recordings, paybills, cast photos of ROSE MARIE in 1924. My mother in law was an orphan. Her mother died in 1935 of an unknown blood disorder. She was a Chicago Socialite that was in the first cast of ROSE MARIE. Betty VanZandt (Elizabeth Margaret VanZandt) was mentioned in Chicago papers as the red haired beauty who sang in Rose Marie. My mother in law knew little about her mom. He father Albert Sobler and he died of a brain tumor. She was a Zigfield girl. Most of her articles were taken from her and her sister when she were placed in a home for orphans. I doubt that recordings of her performances exist, but surely pictures. She was mentioned with Jack Dempsey as well. Can you help?

We have forwarded your question to Kurt Gänzl. Hopefully he will be able to answer this.

Hello,

I was wondering if anyone would have a record/pictures of June Roberts. The American dancer involved in “Totem Tom Tom”. She was my great grandmothers sister and after 1945 my family never saw or heard from her again. Apparently she was trying to run from her husband in France, but nothing was ever recovered about her death or of any other living relatives that may still be in Europe.

The title of the show is hyphenated.