Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

22 May, 2018

Here it is, finally: a full biography of Jetty Treffz (1818-1878), first wife of Johann Strauss and responsible for bringing the composer to the Theater an der Wien and to the world of operetta. The results? Everything from Fledermaus and Zigeunerbaron to Eine Nacht in Venedig and, ultimately, Wiener Blut. It’s surprising that no one has bothered to write this biography earlier, as far as I can see there are only biographical entries in various encyclopedias. The man who now took the task upon himself is Peter Sommeregger, his book is entitled Die drei Leben der Jetty Treffz – der ersten Ehefrau des Walzerkönigs. (“The three lives of Jetty Treffz – first wife of the waltz king.”) It’s a 145 page publication that was financially sponsored by the culture department of the City of Vienna, and via the Mariann Stegmann Foundation. You could say, perfect conditions for a researcher and a great book!

“Die drei Leben der Jetty Treffz” by Peter Sommeregger, 2018.

The three lives the author refers to are Jetty’s early career as an opera singer, touring extensively throughout Europe with the Julien’s Concerts series that travelled the British Isles, then her 20 year relationship with super-rich industrialist Moriz Todesco (1816-1873) with whom she had several illegitimate children, and of course her late 1862 marriage with the much younger Johann Strauss for whom she became a mother-substitute and sexual confidante, as well as an all-important manager of the family business and international career, including the famous trip to the United States.

Strauss’s concert at the Peace Juilee Festival Hall in Boston, 1872. Jetty Treffz helped organize this US tour and joined her husband on the trip.

There is no shortage of things to talk about when dealing with Jetty, described by London’s Morning Post in 1849 as “a handsome woman with a ripe mezzo-soprano voice, a charming style, and great dramatic feeling.” A little earlier, in 1846, she had sung Adalgisa in Bellini’s opera Norma opposite the great Jenny Lind, who many will remember today as a character in the movie The Greatest Showman (and love-interest of Mr. Barnum, played by Hugh Jackman).

Jetty Treffz in 1850, as depicted by George Baxter.

Luckily, the entire Strauss correspondence has been edited and published, so we know very well what part 3 of her life was like and how the Strauss’ family spoke with one another and about each other. The big surprise being how explicitly open Strauss discusses sexual jokes and sexual matters with his world-wise wife. These statements, e.g. about a rubber sex doll which fucks women (invented in the UK) and erotic drawings by Strauss have long been ignored by researchers, because they were considered ‘unworthy’ of a genius like Strauss, as the 2003 catalogue Johann Strauss Ent-arisiert explained, in combination with an exhibition at the Wiener Stadt- und Landesbibliothek.

The 1878 drawing by Johann Strauss showing an opulently proportioned lady. He sent this card entitled “Auf der Seehundjagd in Wyk auf Föhr” to his lawyer Dr. Max Neuda; it shows Mrs. Neuda and contains a highly suggestive poem.

We’re 15 years onwards now, and you’d think that such aspects would be included in the most natural way in a new biography. Also questions about Treffz’s long relationship with Mr. Todesco. Why did he not marry her? Was it just because he was Jewish and she Roman-Catholic? (As Mr. Sommeregger suggests.) Would a sanctioned relationship with an ‘opera singer’ and courtesan have ruined his social standing in Viennese society and at the Habsburg court? How was their relationship viewed by society back then, as documented by letters, protocols, newspaper articles etc? And why was a union with a celebrity like Johann Strauss possible, without causing any scandal? Because they were both ‘artists’ and thus coming from the morally ‘questionable’ world of entertainment?

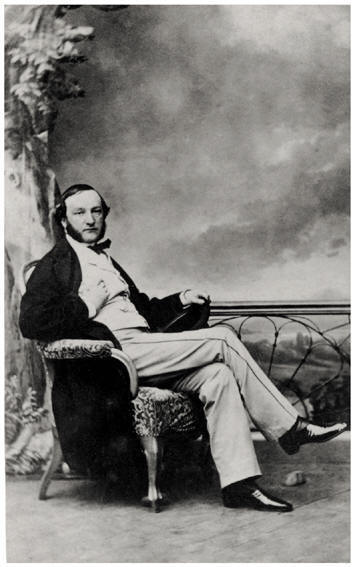

Moriz Todesco, who co-owned the Marienthal and Trumau Incorporated Spinning Mill Company.

The truly annoying thing about Mr. Sommeregger’s book is that he discusses none of these questions. All he says, somewhere along the way, is that her status as an ‘unmarried’ women with several illegitimate children ‘must have been bitter’ for her – and far removed ‘from a bourgeois existence’ (“gutbürgerliche Existenz”). He doesn’t ask whether Jetty actually wanted a bourgeois existence, or whether such an existence would have been possible for someone with her social background. Remember the detailed description of wedding regulations included in the catalogue Sex in Vienna. Desire. Control. Transgression (at the Stadtmuseum Wien, 2016) and the harsh social regulations women (and men) faced back then? It’s not that facts aren’t available to sketch a nuanced social picture in a biography.

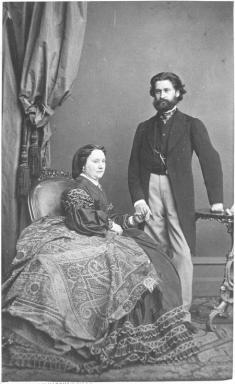

The dashing young composer Johann Strauss and his wife Jetty Treffz, 1862. She brought 7 illegitimate children into the marriage.

Also staggering is the fact that Mr. Sommeregger mentions various divorces (between Jetty’s parents, her daughter, within the Strauss family, especially the Strauss parents etc.) as if such a separation were the most natural/easy thing in the world. Every Johann Strauss Jr. fan knows that the composer had enormous problems with his second wife Angelika Dittrich to get a divorce in Catholic Austria – he had to convert to Protestantism and become a citizen of Coburg to obtain a divorce. Afterwards, he was a social outcast at court in Vienna. It seems that Mr. Sommeregger has never heard of any of this.

Sheet music cover for “Away Now Joyful Riding” showing Jetty Treffz as the singer of that song.

Instead, he’s happy to talk about Jetty’s opera roles, giving the names and dates of composers as footnotes (“Daniel François Auber [1782-1871]: französischer Komponist”). But what Jetty did in the six years when she did not sing publicly and lived by the side of Moriz Todesco instead isn’t worth a single footnote or quote from any society column. We never hear what their life together actually looked like. All he says is: “As well-known as the liason between Moriz and Jetty was within their circle of friends, it was officially never mentioned.” He doesn’t give any evidence for this, nor does he seem to have seriously looked. And when it comes to the other Todesco family members and what they might have said about Jetty and Moriz, Mr. Sommeregger also remains vague. There is only a passing mention of Moriz’s brother Eduard whose wife Sophie set up a famous salon on Vienna – that ran in competition to Jetty’s salon.

The Palais Todesco on Kärntner Street, Vienna, seen in 2006. Sophie Todesco had her salon here, Moriz built a smaller private mansion next door. (Photo: Gryffindor / Wikipedia)

Todesco did adopt his daughters, but not the male offsprings, and he did marry them off very well. And the children were part of Jetty’s later life, with highly contrasting accounts of their relationship to their mother. These accounts are partly quoted in the book, but never analyzed.

Johann Strauss “out-weighing” Jacques Offenbach: a Viennese newspaper caricature from the 1870s.

When we finally get to the operettas Johann Strauss wrote because of Jetty’s influence there is also no attempt to discuss the genre per se – we don’t even hear about Jacques Offenbach and Paris-imported-operettas as role models for Strauss. Franz von Suppé doesn’t pop up either. And what ‘operetta’ meant in Vienna in the 1860s and 70s – as opposed to today – isn’t described in a single sentence. More annoyingly, the fact that Richard Genée was hired to help Strauss write these operettas, with contracts silencing Genée about his substantial compositional contribution, isn’t mentioned either, although Jetty-as-manager must have been instrumental in setting up this deal which only came to light recently when the original scores of Fledermaus etc. became available after restitution cases. It seems Mr. Sommeregger couldn’t be bothered with any of this.

Instead of quoting from historical sources (and there are many), or basing his narrative on historical documents, many descriptions begin with ‘probably’ (“it was probably not easy for her being separated from her children for such a long time”) or ‘it’s very likely.’ I have rarely read anything so embarrassing and badly researched. Why on earth the Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien and the Mariann Stegmann Foundation deemed it necessary to invest money in this project has to remain a question mark. What exactly drew Mr. Sommeregger to Jetty Treffz is also a puzzle, at least to me.

Georg Gaugusch’s “Wer einmal war,” volume L-R.

The level of insight is zero. You might as well read the Wikipedia article on her, and research the rest yourself. If you want to proper portrait of Moriz Todesco, you’ll have to wait until the next volume of Georg Gaugusch’s Wer einmal war: Die jüdischen Familien Wiens 1800-1938 comes out. (The last volume stops at letter R.) And if you want real (fun) facts about Strauss, stick to the letters, edited years ago by Franz Mailer as Leben und Werk in Briefen und Dokumenten.

Should you wonder why I am getting so upset about all of this, the answer is: a year ago Mr. Sommeregger as head of the Frida Leider Society sent me a letter-of-complaint because I had included Frida Leider in a Siegfried Wagner exhibition at Schwules Museum, explaining that there are rumors of her being lesbian and having lived for 30 years with her female partner (who posed as house keeper). Mr. Sommeregger told me off for spreading nonsense, claiming there was no evidence at all for such rumors. (And ignoring the fact that lesbians often – in that time, as today – chose to remain invisible because of social pressure; many married and had children and lived an outwardly heteronormative life, for fear of having their children taken from them.) Now Mr. Sommeregger himself presents a minimal evidence biography that skips over any questions of sexual moral in the 19th century. Instead, he suggests that everyone (including Jetty and Moriz and Johann) shares his own ideal of a “bourgeois existence” – which probably says more about Mr. Sommeregger than the people he writes about.

The book cover states that he has written academic articles for MUGI, the encyclopedia for Music and Gender (“Musik und Gender im Internet”). If this Jetty Treffz biography is any indication of what Sommeregger’s idea of gender research is … then this speaks volumes.

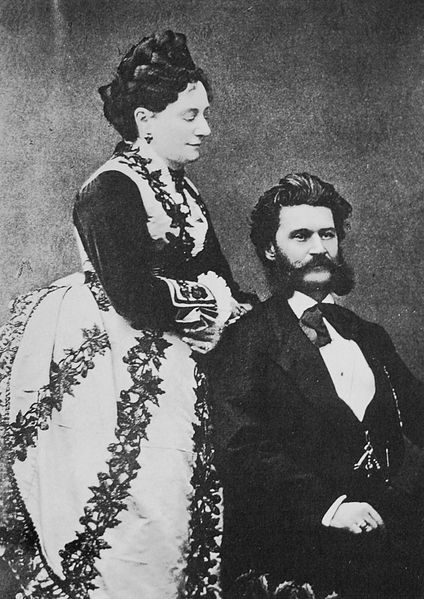

A portrait of Jetty and Johann Strauss.

On the positive side: the descriptions of Jetty’s operatic voice, taken from historic reviews, are fascinating. There surely is more material where this came from, and more source material should definitely be utilized for a proper Jetty Treffz biography, soon. What Moriz Todesco did while his official girl friend was on tour would also be interesting to know, how much he contributed to her wardrobe and how many of his connections she utilized for her artistic career also remains a mystery. Is her appearance in front of Queen Victoria the result of the Todesco influence? Or did Todesco love Jetty because she brought such connections into his (business) life?

You won’t find out in this book.