Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

19 May, 2018

Kurt Gänzl is no stranger to readers of these pages. As the author of The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre and many other well-known works on operetta history, he’s made a name for himself. He also has a blog entitled Kurt of Gerolstein where he posts fascinating biographical articles on 19th century singers, many of them with an operetta/comic opera background. His latest book is entitled Victorian Vocalists. We managed to get Mr. Gänzl to give us an interview on 19th century operetta titles – and their international success. And: about the stars that made these titles such a global phenomenon.

Operetta researcher Kurt Gänzl in Australia, were he spends the summers. (Photo: Private)

If La belle Hélène is the most successful French operetta of the 19th century, what is the most successful Viennese title?

I wouldn’t rate Belle Hélène as #1 of all, but it’s certainly up there on the podium alongside Orphée, Chilperic, La Fille de Mme Angot (my personal fave). I would say the big few of contemporary central Europe would be Bettelstudent (original version), Fatinitza, Boccaccio, Fledermaus, with Bettelstudent getting my gold medal. But we all have our special favorites.

How do you rate what’s most popular in the 19th century? Based on performance statistics (if there are any)? Based on comments by contemporaries? If you single out Bettelstudent then that verdict is based on … personal preference?

I think both. Bettelstudent (original ending, not the modern saccharine ending) is definitely my favorite 19th century ‘Germanic’ operetta. But you go through the contemporary Austrian newspapers (which I have) and my big three were just as often played as Fledermaus. It’s only the 20th century which has deified Fledermaus or rather the name of Johann Strauss. Fledermaus, for example, was not successful in England, America etc. But Boccaccio was a huge hit there! [As was Hélène, of course.]

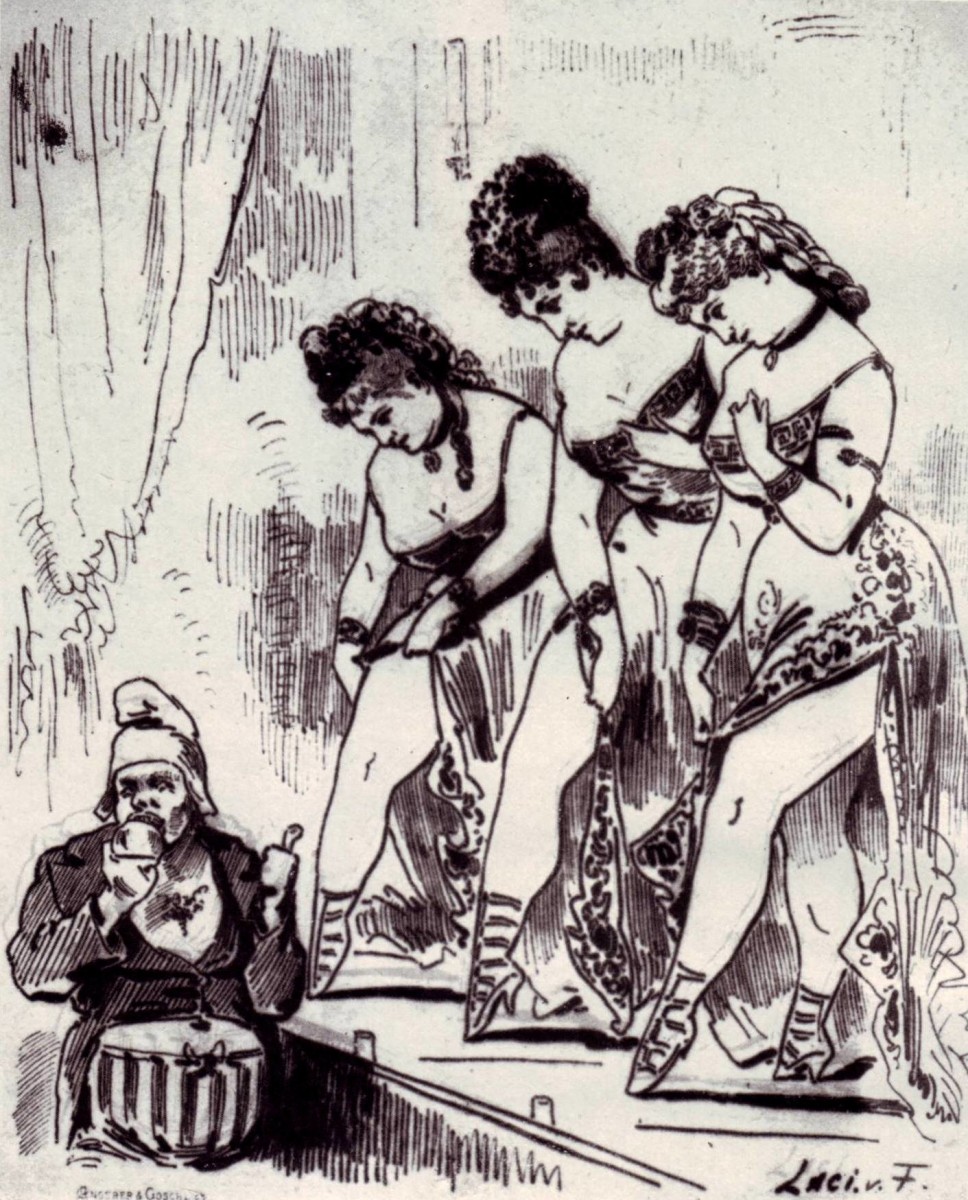

Three Helenas in Vienna, showing off their legs to the theater director in the 1860s.

Hélène was seen, by contemporaries, as the ultimate example of ‘indecency’: it shows matrimonial infidelity on stage, and not just the topic per se, but the actual act of ‘adultery’ in the form of a duet with music by Offenbach, in which the soprano and tenor are in bed – and ‘at it,’ in 6/8 time. How does Boccaccio compare with this? (After all, it’s based on the notorious Decamerone, which was considered for centuries as pornographic literature.)

Like Eurydice and her ‘fly’. All great fun. Boccaccio indeed. It’s all there, inherent in the story. Like much of The Decameron (which I haven’t read for half a century) and works such as The Canterbury Tales matters sexual are the key to the plots and the mover of the action. But in the nineteenth century nearly every French comedy or comic libretto was the same. ‘Indecency’ is in the eyes of the beholder. Remember, the works of Offenbach’s librettists were denounced as a Jewish plot to destabilize Germany by immorality. Really!

A staging of Boccaccio can be as overtly sexual or merely as ‘suggestive’ as it wants. The 19th century found (like me) ‘suggestive’ more titillating. The modern age seems to prefer leaving nothing to the imagination. I saw a very weak and colorless Boccaccio at the Volksoper once where Bumpti-rapata was staged with the cooper raping his wife against a wall. It looked so silly, the audience laughed.

Marie Geistinger as Boccaccio, in Vienna.

How important was a ‘juicy’ lead role for female artists for the success of operetta in the 19th century? (In his recent Offenbach study, Laurence Selenick points out that actresses earned exception salaries with roles such as Genevieve, Hélène, Grand-Duchesse or Périchole. Up to $ 1,200 monthly, paid in gold, while the average leading actress in the best dramatic theaters were paid $ 50 a week. What justified such salaries (and what did they have to do in return) and does the role of Boccaccio fall into this top earning category?

The larger part of the 19th century operetta audience was male, therefore the display of the female form and of female talents was an important part of laying out of a libretto. The casting of a role such as Boccaccio with an actress in travesty was not so unusual: women had been playing young men’s parts, regularly, for a long time. After all, male clothing allowed a much more obvious display of bodily ‘charms’ than the female, where an ankle was regarded as saucy. Likewise the costumes of antiquity … look at a photo of the well-endowed Emily Soldene as Drogan (Genevieve de Brabant) or Hélène! Eliza Vestris as Macheath (The Beggar’s Opera)!

Emily Soldene as Offenbach’s Helena.

I haven’t seen any prima donna’s pay slips (except Soldene’s), and I don’t know what kind of dollars are meant, but I would agree that opéra bouffe and operetta stars were paid better than run-of-the-mill actors and actresses. With dramatic stars, of course, the sky was the limit. (And let’s not forget, in the absence of primary proof, the old adage ‘I’ll pay you 50 a week, and tell the press I’m paying you 200.’)

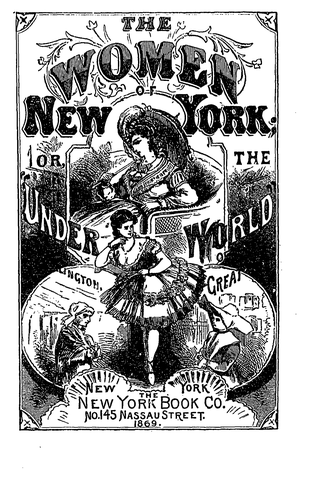

Mr. Selenick gives George Ellington’s 1870 book The women of New York, or Social life in the great city as his source for the ‘gilded’ salary figures. Ellington also wrote The Women of New York; or, The Under-World of the Great City a year earlier: “Illustrating the Life of Women of Fashion, Women of Pleasure, Actresses and Ballet Girls, Saloon Girls, Pickpockets and Shoplifters, Artists’ Female Models, Women-of-the-Town.”

George Ellington’s 1869 “The Women of New York; or, The Under-World of the Great City.”

I would think that Antonie Link – the world’s first Boccaccio in 1879 at the Carltheater in Vienna – fell into the ‘star’ category and would have been paid accordingly. I think whoever played the role in Amstetten or Salzburg would not! Justified? Just as today, a performer is ‘worth’ only as much as he or she brings in in ticket sales. And Link and Boccaccio were big draws.

Antonie Link as Wladimir Dimitrowitsch Samoiloff, (Lieutenant of a Circassian Cavalry Regiment) in Suppé’s “Fatinitza.” It’s a role she created in 1876.

Suppé is often seen as ‘slightly boring,’ today. As ‘classical’ and ‘restrained’ next to mad-cap Offenbach. Is that was his contemporaries said too about his music? Is it time to re-consider our evaluation of Suppé and understand him in a new way?

Suppé was a working conductor with a huge workload. I just updated his theatrical worklist the other day. It runs for pages and pages. He composed all sorts – I don’t think the scores for his burlesques, for example, would be regarded as ‘restrained’ or ‘boring’. The tiny portion of Suppé’s work that is generally known today is made up of his most ambitious works. And it contains jewels of composition: the ladies’ trio in Boccaccio, the chorus and march in Fatinitza … the equal, I think, of anything in, for example, of Les Contes d’Hoffman. I think it is foolish to blame him for ‘not being Offenbach.’ Everybody was not Offenbach; or Hervé. In my opinion, Suppé and Millöcker are unjustly neglected, in our German day, in favor of the ‘buzzword’ Strauss, whose theatrical output isn’t their equal. And if they ‘weren’t Offenbach’, why shouldn’t one like camembert and Emmenthaler?

Poster for a “Boccaccio” production in London, 1882.

There are various recordings floating around, e.g. the EMI full cast album with Anneliese Rothenberger. Do they give an adequate idea of what made Boccaccio so successful a century ago?

It’s long while since I listened to them, for Musical Theatre on Record, which I don’t have by me. I can’t remember what I said. I remember best the ladies trio … but I suspect they were all (given the period) rather beautifully sung and rather straight-laced. Also, fatally, with a baritone or tenor in the title-role. Am I right?

Have you seen Boccaccio on stage yourself? How would you describe the performance you saw as opposed to the performances you read about in the 19th century?

Yes. I flew from France to Vienna especially to see the piece at the Volksoper. They had done a great job of Bettelstudent (with the wrong ending), so I was excited. It was one of the biggest disappointments of my theatrical life. A director so ineffably, unimaginatively bad … and poor Mr. Bo Skovhus being a mezzo-soprano substitute amid acres of grey, grey, greyness. I was in press seats, but nevertheless I stood up, booed, and turned my back on the stage. So, you might say, I haven’t really seen Boccaccio. The piece was never so clumsily treated in the 19th century. The Decameron is good, sexy, fun. The operetta ditto. Modern directors, alas, seem incapable of getting that flavor. They get some gimmick and give it preference over all: even altering text and score if it doesn’t fit with their preconception.

If I look at books such as Richard Traubner’s Operetta: A Theatrical History, Boccaccio doesn’t get a special mention. Why has the show dropped out of the general operetta discussion (and when did this happen)?

It hasn’t dropped out of mine! (laughs) As I said, Bettelstudent, Boccaccio and Fatinitza are the central European medal-winners of my 19th century. I think Richard probably didn’t really know the piece …

But you are right. Ask even a Viennese to name half a dozen 19th century operettas. They’ll say Fledermaus, Zigeunerbaron …. ummmm. Suppé and Millöcker aren’t buzzwords, I’m afraid. So their shows don’t get done. So nobody knows them. So nobody does them. They drag out Fledermaus once more. Get a life, guys!

The two big Viennese titles everyone knows today are Fledermaus and Lustige Witwe. The Strauss operetta is also about adultery, the Lehár operetta about suppressed sexual longing that breaks free in a “waltz without words” at the end. How important is adultery and sex for 20th century operetta and operetta audiences?

Oh, very important. Both Fledermaus and Witwe are based fairly and squarely on French comedies, and French comedy quite simply lived, breathed and breakfasted on matters sexual. Mind you, it helped that the works of Meilhac, Halévy and their compatriots were also the most skillfully constructed and written and literate stage pieces of their era. I have their Complete Works in umpteen volumes on my bookcase and return to them frequently. A joy! (It would be fun to see a Fledermaus musical done to the original text!).

If Boccaccio was once successful because of the ‘kinky’ stuff in it, why hasn’t our age of Kinky Boots rediscovered Suppé’s masterwork on a grand scale?

Kinky? I don’t find it kinky! I just find it good rollicking fun, of the Canterbury Tales kind, set to first-class comic opera music … and, well, it just needs one colorful, skilful, well-cast production of the piece as it was written … let’s hope it happens!

kevin, thanks for the article post.Really thank you! Great.