Roland H. Dippel

Originally published in Das Orchester, January 2026 (translated and published here with permission of the author)

14 December, 2025

At long last, there is some movement in the engagement with “Heiteres Musiktheater”. In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), this was the institutional, formal, and theoretical umbrella term for what in the West was long referred to as “popular musical theatre” — operettas, musicals, musical comedies, and hybrid forms. Socialism had neither an independent commercial theatre scene nor musical hubs such as Broadway or the West End; instead, it maintained dedicated repertory theatres for operetta and musical.

Various famous operettas from Eastern Germany, as presented on an LP cover in the GDR.

These houses were among the cultural flagships of the socialist system, at a time when Western venues such as Munich’s Gärtnerplatz Theatre or the Vienna Volksoper increasingly shifted their focus toward opera from the 1960s onward.

A Surge of Premieres in the 2025/26 Season

This season alone, four new productions of works created in the GDR can be seen in (Eastern) Germany: Gerd Natschinski’s Messeschlager Gisela (1960) at the Staatstheater Cottbus; Guido Masanetz’s In Frisco ist der Teufel los (1962) as the Komische Oper Berlin’s “Christmas operetta”; followed in winter 2026 by Natschinski’s Mein Freund Bunbury (1964) at the Eduard-von-Winterstein-Theater Annaberg-Buchholz and at the Landesbühnen Sachsen. This concentration is encouraging. A cycle of GDR operettas and musicals currently under consideration at the Komische Oper Berlin could generate a signal effect similar to that once achieved by Barrie Kosky’s series devoted to twentieth-century operettas and “classic” U.S. musicals.

Yet even 36 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall — and after the final world premiere, Masanetz’s Eine unmögliche Frau on 13 May 1990 in Annaberg — the long-overdue, broad-based reassessment has still not taken place. This temporal distance is comparable to the period between the end of the Second World War in 1945 and the NATO Double-Track Decision of 1979. Operettas premiered during the Third Reich, such as Die ungarische Hochzeit, Maske in Blau, and Hochzeitsnacht im Paradies, remained successful in West Germany. In the GDR, by contrast, the operetta tradition from Kálmán to Künneke was largely dismissed — with few exceptions — as “late-bourgeois decadence” and a “capitalist industry of stupefaction.”

Ironically, this very disparagement triggered a wave of enthusiasm in Eastern Germany during the 1990s for early twentieth-century operetta, while publicly funded theatres in the “old” Federal Republic increasingly embraced the musical. Meanwhile, the GDR’s own counter-reaction to the alleged decline of the genre — more than 200 new works composed between 1949 and 1990 — remained largely ignored and insufficiently researched in reunified Germany, as well as in Austria and Switzerland. To this day.

Missed Initiatives and Fragmentary Rediscovery

There were repeated attempts to address this repertoire, though none provided a decisive impulse. The Gesellschaft für unterhaltende Bühnenkunst initiated efforts that were later continued by the Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik at the University of Freiburg, where the online project „Ur- und Erstaufführungen des populären Musiktheaters im deutschsprachigen Raum seit 1945“was developed.

The ladies of the ballet in “Messeschlager Gisela,” at the Staatsoperette Dresden 1961. (From: Andreas Schwarze’s “Metropole des Vergnügens,” Sax-Phon Press 2016)

Around 2000, the wave of “Ostalgie” (nostalgia for East Germany) produced a modest revival with productions of Messeschlager Gisela, Mein Freund Bunbury, Natschinski’s Servus Peter (1961), and stage adaptations of the film musical Heißer Sommer (1968). In 2015, the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig honored composer Guido Masanetz on his 101st birthday with semi-staged performances of In Frisco ist der Teufel los. Later rediscoveries included Gerhard Kneifel’s musical Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten (1970), based on the farce Der Raub der Sabinerinnen, staged in Leipzig in 2020, and Harry Sander’s Prinz von Preußen, an adaptation of Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1978), produced at the Gerhart Hauptmann Theatre in Görlitz in 2023. These were among the most “exotic” revivals to date.

Yet even these two highly successful productions failed to spark broader curiosity among theatre professionals about the extensive GDR repertoire — regrettably so.

Perspectives of the Heirs: Masanetz and Natschinski

Sibylle Masanetz, widow of the composer who died in 2015, cited one reason for this neglect: “In the old Federal Republic, much of the GDR’s output remained unknown. This tendency persisted long after the fall of the Wall, also because many leadership positions in theatres in the new federal states were filled with personnel from the West.”

She added candidly: “I always believed that the quality of my husband’s works would automatically generate interest among theatres and opera houses. That was not the case.”

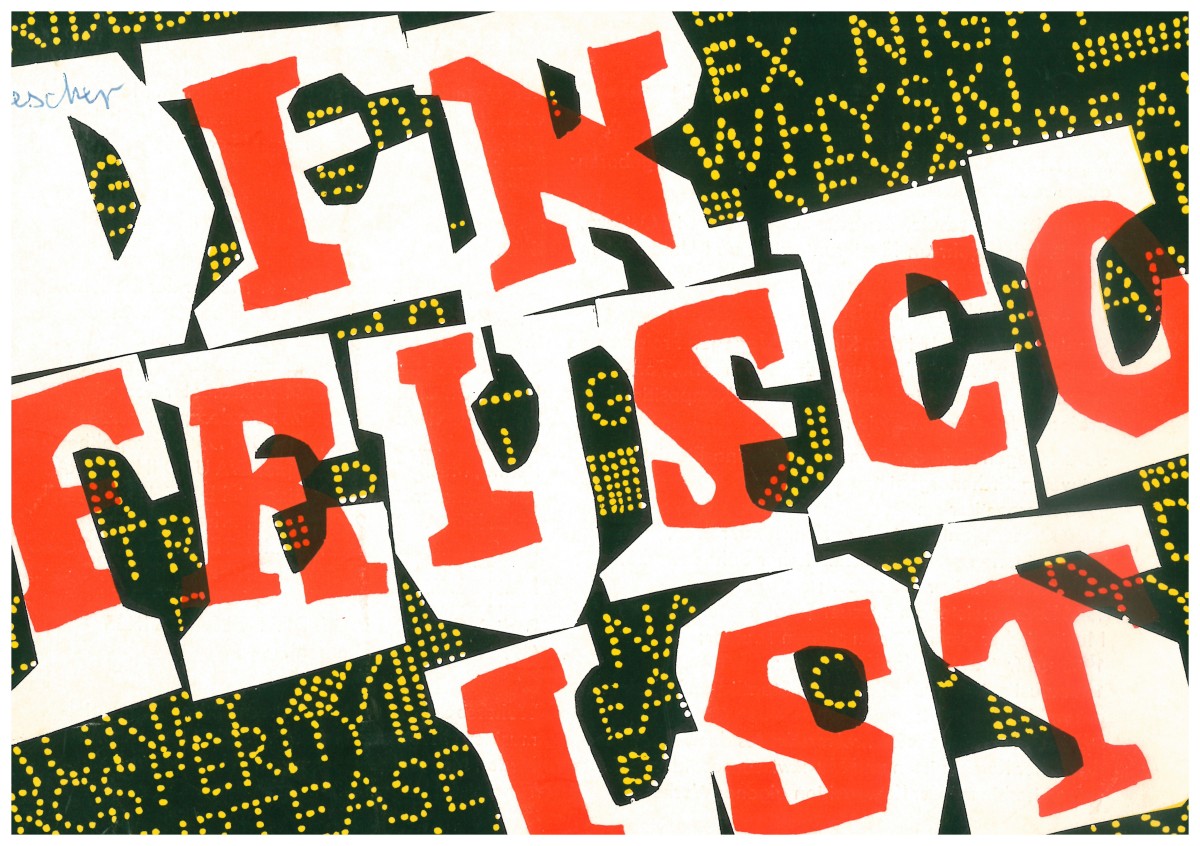

Cover of a program for “In Frisco ist der Teufel los” from 1965. (Photo: Archiv of the Operetta Research Center)

Another factor was the transfer of GDR publishing archives to other publishers. Music theatre works originally issued by Henschel Verlag and the state-owned VEB Lied der Zeit are now distributed by Bärenreiter and Schott. After reunification, some “classic” operetta recordings from the GDR labels Eterna, Amiga, and Nova were reissued on CD — but not works of “Heiteres Musiktheater”, Even Piper’s Encyclopedia of Music Theatre and Volker Klotz’s influential standard work Operette largely ignored East German production. Only YouTube eventually enabled more fruitful research.

The paperback edition of Volker Klotz’s 1991 (Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst,” at Piper.

For years, Schott and Bärenreiter were occupied with reviewing and cataloguing often incomplete performance materials. Their parallel initiatives to enhance visibility may now begin to bear fruit. Bärenreiter recently repositioned the GDR repertoire through a scholarly essay by Katrin Stöck. In spring 2025, Schott published an annotated catalogue in which “Heiteres Musiktheater”in the GDR is presented on equal footing with “Operetta and Musical” in the Federal Republic and after 1989, alongside the Parisian, Viennese, and Berlin operetta traditions.

Equally active is Gundula Natschinski, widow of Gerd Natschinski, in safeguarding her husband’s compositional legacy. Her son Lukas, from her marriage to the composer, is an energetic collaborator. He will conduct the new production of Mein Freund Bunbury in Annaberg-Buchholz, while his mother will appear there as Lady Bracknell, singing the evergreen “Ein bisschen Horror und ein bisschen Sex.” Naturally, the family also welcomed the Cottbus revival of Messeschlager Gisela in Axel Ranisch’s adaptation for the Komische Oper Berlin’s theatre tent at the Rotes Rathaus in 2024.

The whole ensemble on the “Messeschlager Gisela” production at Staatstheater Cottbus, 2025. (Photo: Bernd Schönberger)

Nevertheless, these successes represent less an expansion of territory than a defense of existing ground. The Staatstheater Cottbus remains the only subsidized theatre to have staged Messeschlager Gisela twice since 1989. The first production, in 1998, was directed by Steffen Piontek, who later also presented Servus Peter and Heißer Sommer during his tenure at the Volkstheater Rostock. In Annaberg, Mein Freund Bunbury is only the second new staging since reunification. After the ebbing of the Ostalgie wave, even performances of this former blockbuster became rarer. Why?

Strong Works as Burden, Stigma, and Historical Document

“Do you really think anyone is still interested in this today?” was the response given in 2016 by Roland Seiffarth when asked about this repertoire. Before the fall of the Wall, the long-serving chief conductor of the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig had shown greater commitment to GDR premieres of works by Robert Stolz than to new compositions from his own country — with the exceptions of Kneifel, Masanetz, and Natschinski.

After the heyday from the late 1950s to around 1975, “Heiteres Musiktheater” was declared to be in crisis, as the planned output of successful works failed to materialize. Numerous productions were mounted, including Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten, Conny Odd’s Karambolage (1969), and Siegfried Schäfer’s Verlieb dich nicht in eine Heilige (1969). After reunification, the genre vanished abruptly, not least because key protagonists fell silent. Klaus Eidam, chief dramaturg of the Dresden State Operetta and a respected librettist, was no longer accessible for inquiries. After Caballero (1988) and the fall of the Wall, Natschinski showed no further ambition to write stage works and would have preferred Steffen Piontek’s 1998 Cottbus production to tackle one of his historical subjects such as Casanova rather than the contemporary Messeschlager Gisela. Before the First German Musical Congress in 1995, it was primarily interested parties from western Germany who catalogued and salvaged materials ahead of the large-scale dismantling of GDR cultural institutions.

Internal Conflicts and Self-Denigration

Even within the GDR, the positioning of “Heiteres Musiktheater” was cautious. Its stars were not cultural ambassadors of the state like opera singers Theo Adam or Ute Trekel-Burckhardt. Performers such as Gunter Sonneson and Dagmar Frederic expanded their careers toward West Germany only after reunification. The artistic potential of Eva-Maria Hagen — Gerd Natschinski’s creative companion from Messeschlager Gisela through Terzett to ABC der Liebe (Dekameronical) — and recordings of Frisco, Bunbury, and Conny Odd’s Alarm in Pont L’Evêque with Gisela May never approached the public recognition of the artists’ other achievements. The performers themselves showed little interest in integrating “Heiteres Musiktheater” into their public image.

The LP cover of Masanetz’s greatest stage success, “In Frisco ist der Teufel los”.

In the 1990s, neither the Staatsoperette Dresden nor the Metropol Theatre Berlin advocated for the marginalized cultural heritage that lay squarely within their remit. Even before 1989, repeated trials of legitimacy weighed heavily on artistic self-confidence. Officially, “Heiteres Musiktheater” in the GDR was categorized on equal footing with opera, drama, and dance. Internally, however, the fear of devaluation was profound. Erwin Leister, chief director of the Musikalische Komödie and director of a GDR television adaptation of Messeschlager Gisela, spent decades in Leipzig striving for recognition of “his art.” Now over 100 years old and still following the scene with keen interest as a respected adviser, Leister speaks bluntly of the “schizophrenia” inherent in the responsibility for “Heiteres Musiktheater”: its anarchic potential — which did exist in GDR operettas and musicals — was never fully exploited.

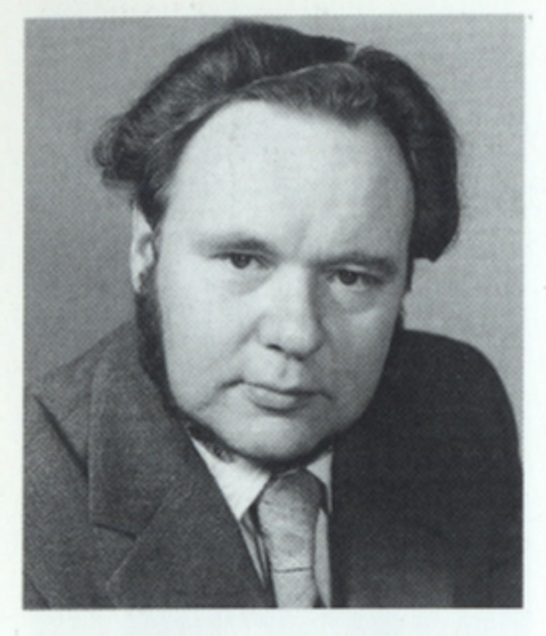

Composer Gerd Natschinski. (Photo: William Pauli)

This sense of inferiority, felt even in everyday theatrical practice, was compounded after reunification by the awareness of being condemned to irrelevance and collective oblivion. Contributions in opera and spoken drama, by contrast, were acknowledged. Paul Dessau’s The Condemnation of Lucullus, staged by Ruth Berghaus at the Berlin State Opera, was long celebrated as an exemplary fossil of a historical era. The disappearance of light musical theatre from the GDR — into which considerable time and energy had been invested — thus represented a stigma both before and after 1989. Hardly any contemporary witness of “Heiteres Musiktheater” expresses pride in having been part of history or in having shaped an enduring component of GDR culture. Such pride would correspond to defining a British-American cultural identity without Broadway or the West End.

Opportunities and Broader Visibility

These internal conflicts remain largely hidden from the public. Most revivals of GDR musicals — such as the Bunbury production that remained in the Leipzig repertoire for 20 years — adhered to GDR-era directing styles and appealed to nostalgic impulses among eastern German audiences. This changed only in 2019 at the Brandenburg Theatre with Frank Martin Widmaier’s production of Bunbury. Casting “East German stars” Dagmar Frederic and Gunter Sonneson, Widmaier opted for a contemporary, partially stylized aesthetic, demonstrating that this GDR flagship work could succeed with both older and younger audiences without nostalgic trappings.

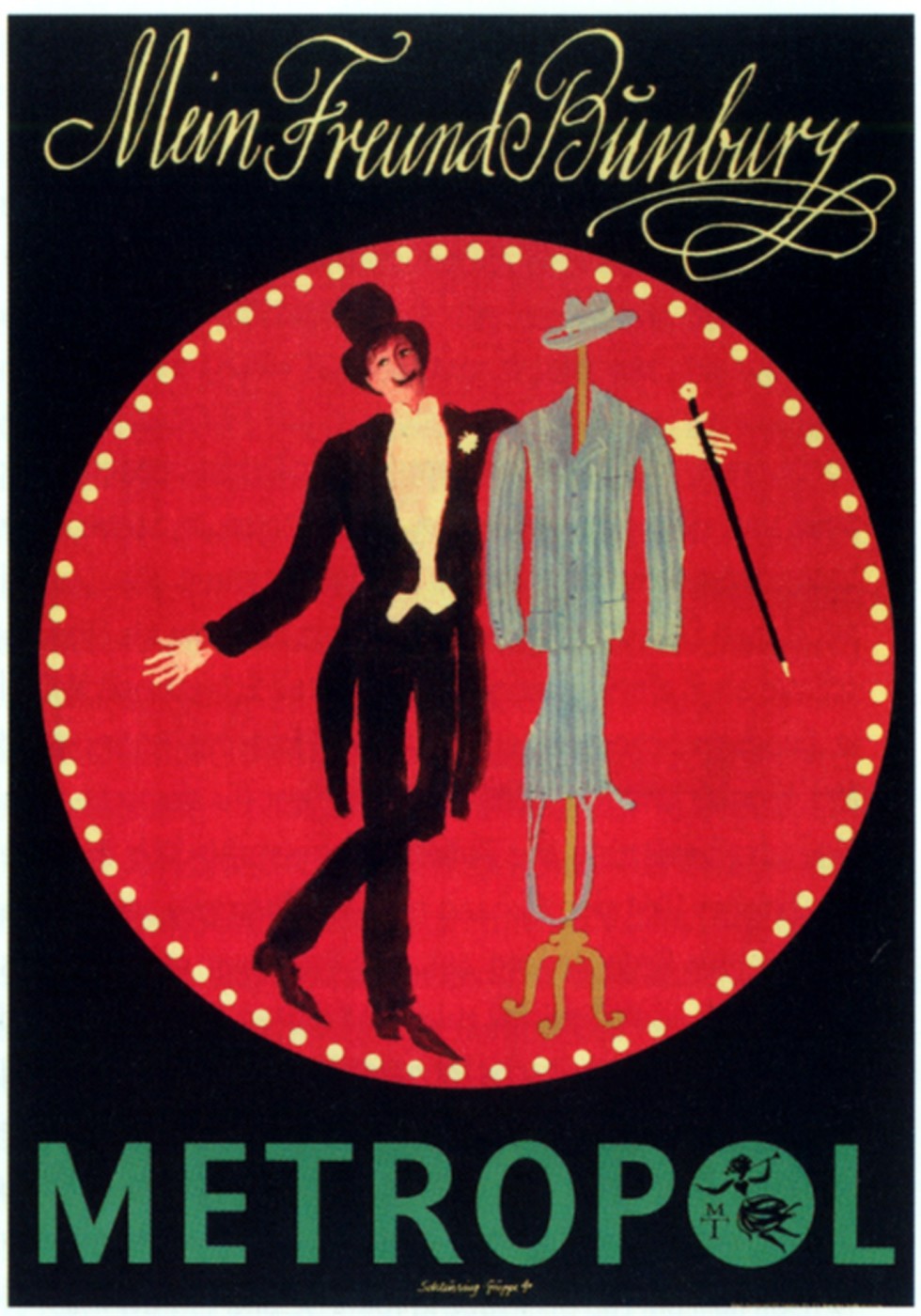

Poster for “Mein Freund Bunbury” at the Metropol Theater in East-Berlin, 1973.

Axel Ranisch, in his Berlin staging and adaptation, gently ironized the Leipzig Trade Fair setting of Messeschlager Gisela at its 1960 premiere. He did not fundamentally alter the narrative of corruption within the state-owned fashion enterprise VEB Berliner Chic, merely clarifying certain elements for younger viewers and intensifying the erotic pluralism. In this version, Inge is a cutter — who, unlike in Ranisch’s own production at Katja Wolff’s staging in Cottbus, goes away empty-handed. The strength of the Cottbus production, as in Brandenburg, lies in its renunciation of nostalgic, symbolic, critical, or realist “East German charm,” thereby proving the work’s vitality beyond theatrical visibility dependent on the GDR past.

In this respect, Martin G. Berger’s staging of In Frisco ist der Teufel los at the Schillertheater is of major significance for the current state of rediscovery. Berger consistently takes the narrative and its concerns seriously in his operetta productions, while offering an innovative, critical, and contemporary approach. This season thus marks the rare opportunity to see three major operetta and musical works from the GDR on stages in the new federal states.

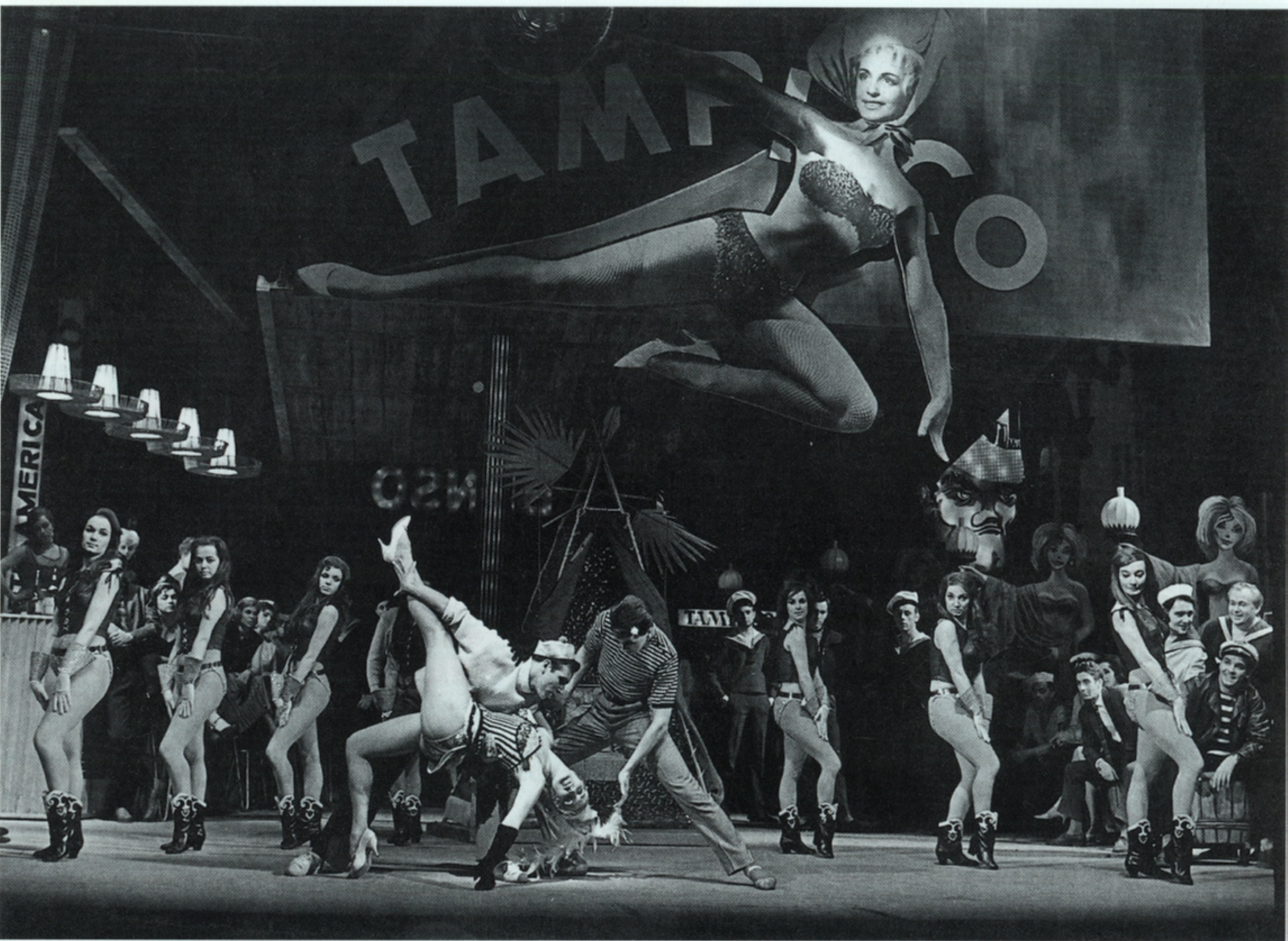

A scene from “In Frisco ist der Teufel los,” 1962.

Many other titles would also merit attention. One example is Masanetz’s operetta Mein schöner Benjamino (1963). The story of the “horse bride” Brigitta, who celebrates her “handsome Benjamino” as her “finest cavalier,” and her twin sister Marlis, raised in West Germany, ran for only a few performances. After the construction of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961, the West virtually disappeared from GDR stages, and acute political events thoroughly undermined the work’s relevance. Traces and pasted-over passages in the libretto suggest that the hotel “Zum rüstigen Tiroler” was originally located in the West German Alpine foothills rather than in the GDR district of Suhl.

Other works, too, promise — at a historical distance — less frivolity and more satirical edge, along with unexpected musical discoveries. One might choose among titles such as Irene und die Kapitäne, Damals in Prag, Ein Fall für Sherlock Holmes, or Vasantasena…

Roland H. Dippel has been intensively engaged with GDR popular musical theatre since 1993, following a suggestion by director Wilfried Serauky. Among other publications, he authored a 15-part series on the subject in the Leipziger Volkszeitung from 2015 onward, contributed to the annotated Schott catalogue Operettas & Musicals (2025), and wrote the entry “Heiteres Musiktheater” for the online platform Music History Online: GDR.