Michael D. Miller

Operetta Foundation Los Angeles

31 October, 2020

In 2013 and 2016 the University of British Columbia performed two of Emmerich Kálmán’s early symphonic poems, Saturnalia and Endre és Johanna, a recording of those concerts was made. Now, it is possible to hear these works for the first times on a CD released by the Operetta Foundation in Los Angeles, part of their ongoing campaign to make important Kálmán works and recordings newly available. In the booklet for the new disc, Michael D. Miller as long-time Kálmán crusader and head of the Operetta Foundation explains what’s special about Saturnalia and Endre és Johanna. He also discusses the other titles on the album, including forgotten music from Gräfin Mariza and a composition by Charles Kálmán.

The cover of the new CD with Emmerich Kálmán’s Symphomic Poems. (Photo: Operetta Archives)

“Today, with a certain shyness, Kálmán hides his debut works from the eyes of the public. His symphonic works Saturnalia and Endre és Johanna are never performed.… Kálmán let me look through the full score of his Saturnalia.… You feel sorry for these first creations of the Master. But as reality led him on quite a different path, one feels inclined to be grateful all the same.… Kálmán has become that delightful smiling musician who, however, knows all too well that mankind is disposed to crying now and then.” These words (here in English translation) were penned in 1932 by music critic Julius Bistron and are included in his biography of Kálmán in commemoration of the composer’s 50th birthday. Kálmán’s first quarter century was filled with intertwined delights and disappointments—contrasts that would, for his remaining almost half century, define both his persona and the tension-racked ebb and flow of emotions that musically permeate dramatic encounters in his operettas.

Despite continuing research, we know relatively little about Emmerich Kálmán’s initial forays into composition. The earliest work mentioned in his memoirs was a 1902 song cycle—now lost, and perhaps never performed—to poetry of Ludwig Jacobowski. His first produced works, programmed in a 1903 concert at the Budapest Academy of Music, were a Scherzando for String Orchestra, the first movement of a piano sonata, and some piano pieces.

A man cycling across a bridge in Budapest. (Photo: Viktor Keri / Unsplash)

A reviewer spoke of “the most beautiful effects out of the string orchestra” and wrote of a sonata movement of “grand scale with virtuoso fingering.” Kálmán’s contribution, the next year, to the Academy’s graduation concert was a symphonic poem titled Saturnalia (premiere: February 29, 1904 in Budapest), a musical depiction of the traditional wild revelries in honor of the Roman god Saturn. With orchestral and harmonic palettes reminiscent of the symphonic poems of the composer’s countryman Franz Liszt, the work also bore, most obviously, the influences of Saint-Saëns, Richard Strauss, and Brahms. The German-language Budapest newspaper Pester Lloyd spoke of “a major coloristic talent in the making,” a composer who “commands the modern orchestra effects surprisingly securely in a nearly virtuoso manner,” and a work that “speaks decidedly of talent.”

Kálmán biographer Stefan Frey reminds us that the work—seemingly far from the world of operetta—nevertheless betrays the composer’s penchant for alternating musical moods between “tears and laughter, ecstasy and melancholy,” a trademark that he would increasingly exploit as his operetta career later blossomed.

In April of 1905, a concert of the National Association of Hungarian Musicians included not only Saturnalia, but also an overture titled Endre és Johanna (Andrew and Johanna) by Ladislaus Toldy. Kálmán, through his reading and musical leanings, had become very interested in “fantastic and somber subjects,” particularly from Hungarian history. This work, no doubt inspired by Eugen Rákosi’s 1902 play of the same title, dealt with the ultimately tragic 14th-century marriage—when they were both about six years old—between Johanna, granddaughter of King Robert the Wise of Naples, and her cousin Andrew, son of King Charles I of Hungary.

A view of Budapest at night. (Dan Freeman / Unsplash)

It must have caught Kálmán’s attention, for nine months later in a concert of the Budapest Philharmonic on January 24, 1906, he premiered his own musical version of the tale. What started out, in conception, as simply an overture to Rákosi’s drama was expanded into a 24-minute tone poem for large orchestra that, for all its orchestral color, never really gels. As Frey notes: “The music never seems to come to rest. Hardly has a lyrical phrase flowered than the king-sized orchestra sweeps it away.” The composer himself minced no words, later in life, in recalling this work as “a real, old, crappy cavalry boot.” There is no record of performances in the years immediately following the premiere, although in 1933 conductor/historian/composer Max Schönherr conducted the work for the Vienna Radio. The performance at the University of British Columbia in 2016 appears to be the first since this broadcast.

Emmerich Kalman as a young man in 1909, the year of his “Herbstmanöver” success.

In December of 1906, the European press announced that Kálmán was working on a one-act opera, with libretto by Franz Ferenczy, based on Oscar Wilde’s 1891 short story The Birthday of the Infanta. There was no further mention of this work and Kálmán himself made no reference to it in the rather extensive memoirs of his early life that he created for Bistron’s book in 1932. Despite some favorable reviews of his earlier serious works, particularly Saturnalia, Kálmán was unable to secure a publisher and, in a reputed fit of desperation, turned to operetta. The curtain had not even gone up at the 1908 Budapest premiere of his first operetta when the audience must have sensed that a new talent was looming.

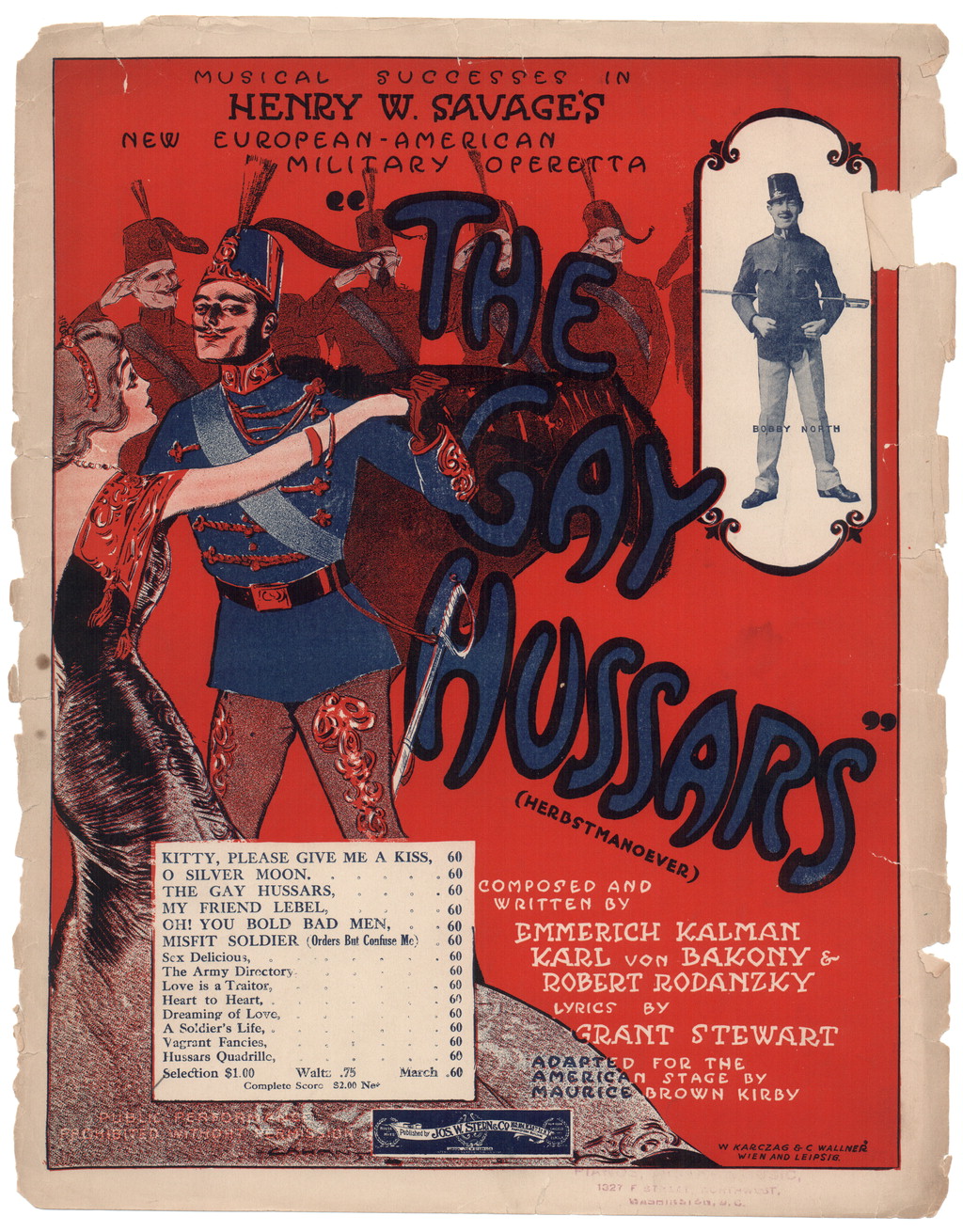

The overture to Tatárjárás (Ein Herbstmanöver when it came to Vienna) remains one of the most exciting in all of operetta, unabashedly capturing the military theme of the show’s storyline, but punctuated midway by one of Kálmán’s most sublime, and soon-to-be trademark, slow haunting waltzes. (A review of the recent complete Herbstmanöver recording on OEHMS Classics can be found here.)

Musical selections from the Broadway production of “The Gay Hussars”, based on “Ein Herbstmanöver”, as published by Jos. W. Stern & Co., New York, 1909. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In the third act of Kálmán’s 1924 operetta Countess Maritza, the penniless Count Tassilo, recently fired from his job as bailiff on the wealthy Maritza’s estate, laments, in his aria “Fein könnt’ auf der Welt es sein,” that although women continually have the upper hand over men, we should all be glad that they are here to stay. Amazingly and regrettably, this most beautiful song is often cut from productions of the operetta.

Composer Emmerich Kálmán at the height of this success, in 1926.

As the curtain rises on Kálmán’s 1915 The Gypsy Princess, cabaret singer Sylva Varescu is regaling the crowd at a Budapest nightclub with a passionate song, “Heia, heia,” about her mountainous homeland and the fiery passion of a Magyar maiden who seeks nothing more than an equally lustful partner.

Charles Kálmán, born in Vienna in 1929, began writing music seriously while a student at Columbia University in New York City. From operettas to musical comedies to film scores, from orchestral suites to concertos, and from waltz to galop, he carved out a highly successful 65-year career, adapting to changing styles, but never abandoning the old-world musical influences from his father and his contemporaries.

Charles Kalman sitting at his grand piano, in the Munich apartment on Maximilianstraße, 2006. (Photo: Operetta Foundation)

The waltz La Parisienne is totally charming: for a moment, one hears shades of Chabrier, then Ravel, then Khachaturian, and then, with the glorious waltz tune two minutes into the piece, maybe a title love theme for a Hollywood film.

It was while preparing musical materials for the UBCSO performance of his father’s Endre és Johanna that, sadly, Charles passed away on February 22, 2015.

You can order the CD directly via the Operetta Foundation in Los Angeles.

Dear Sir,

My name is Tibor Gátay and I am librarian of Budapest Festival Orchestra.

I have one question about the Kálmán CD. Please tell me the information where can I find the performing material of the two symphonic poems of Kálmán.

Best wishes,

Tibor Gátay

librarian of BFO

I am so happy to hear about a CD release of Kálmán’s early symphonic works. I’ve always been curious about composers’ unknown side, and I read about them in the booklet of the Cpo CD of Kálmán’s artsongs (those should get to be known and sung at lieder recitals, they’re truly beautiful!) and I was hoping that someone somewhere would be adventurous, if not crazy enough to record them, and just today, I read your article about them.

Merci beaucoup for your wonderful website!

Sincerely from Taipei