Michael Miller

Operetta Foundation

22 July, 2020

Because of the required commitment of time, money, and dedication, it is a safe bet, with the exception of the Bloom/Bialystock pairing in The Producers, that no production or creative team heads into a Broadway-bound musical project with any goal or expectation other than fashioning a hit show. The formula for doing so, however – after more than 150 years, 3000 Broadway musicals, and perhaps even more shows that closed out-of-town – remains almost totally elusive.

The world-premiere recording of Walter Jurmann’s “Windy City,” released by the Operetta Foundation in 2020 in their “Musicals Lost & Found” series.

As borne out by historical evidence, neither songwriting talent (Kern and Hammerstein’s Very Warm for May), star quality (Maureen O’Hara in Sammy Fain and Pearl S. Buck’s Christine), past success (the 1974 revival, featuring Alice Faye, of the 1927 hit Good News), nor good source material (Doctor Zhivago) is sufficient by itself, or even in combination, to ensure success.

In fact, many of the most notable flops in Broadway history were strong across the board in several of these categories. Years later, in many cases, those involved are still scratching their heads—trying to understand what failed, why it failed, and what, if anything, they might have done differently.

Once in a while, there is a second chance. Bernstein’s Candide was a 73-performance flop when it opened on Broadway in 1956, yet bounced back almost two decades later, achieving more than a tenfold increase in performances.

The original 1956 cast album of “Candide.” (Photo: Columbia Records)

A prime example of the above phenomenology, although it hasn’t yet been given a second chance on stage, is the 1946 musical Windy City (not to be confused with the 1982 British musical with the same title). Inferring from press reports, confidence must have been riding high as the stellar show team was assembled. Music was by Walter Jurmann, who was born in Vienna and became one of the most popular composers of popular tunes (Schlager) in both his hometown and Berlin.

He was forced to emigrate, first to Paris and then to America, where he wrote songs for more than two dozen films (including the well-known San Francisco for the same-named 1936 film with Jeanette MacDonald, Clark Gable, and Spencer Tracy).

Windy City lyrics were courtesy of New York City-born Paul Francis Webster, who had achieved a hit in 1932 with his first song, Masquerade (music by John Jacob Loeb), and later contributed song lyrics to dozens of films (featuring Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, etc.) and to Duke Ellington’s 1941 all-black musical revue Jump for Joy. He would go on, in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, to receive 16 Oscar Best Song nominations, winning three times.

The Creative Team

The book was by Chicago native Philip Yordan, who earned a law degree in 1936, but soon turned his attention to Hollywood, serving as producer on 21 films and eventually garnering three Oscar nominations (Best Story winner), Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Screenplay). His 1944 play Anna Lucasta, adapted for presentation by the American Negro Theatre, played almost 1000 performances.

The extensive dance elements of Windy City were assigned to pioneering black dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham, who gave up a promising career in anthropology to focus on Broadway and Hollywood. Set design was by Jo Mielziner, one of the century’s most influential forces in shaping the “look” of Broadway.

The show was produced by Richard Kollmar, who had begun his Broadway life as an actor (Knickerbocker Holiday, Too Many Girls) and then turned to producing (Early to Bed, Plain and Fancy). Orchestrations were by Don Walker, who by 1946 had more than 30 Broadway shows (On the Town, Carousel) under his belt, and would go on to score Finian’s Rainbow, Call Me Madam, The Pajama Game, The Music Man, Fiddler on the Roof, Cabaret, and Shenandoah, among dozens of others.

Although the two romantic leads were taken by musical theater unknowns Susan Miller (whose main-stage career evaporated after Windy City) and John Conte (who later carved out a career in stage, film, and television), the cast also featured noted vaudeville comedians Joey Faye and Al Shean (of Gallagher and Shean fame, and the uncle of the Marx Brothers), Patricia Neway (13 years later the mother abbess in The Sound of Music on Broadway), and racy burlesque striptease artist Lili St. Cyr.

The “Windy City” New Haven tryout window card.

So … what happened? Windy City opened in New Haven on April 18, 1946, in Philadelphia on April 23, in Boston on April 30, and in Chicago on May 16. Per usual during this out-of-town tryout period, the book was tweaked and songs were added, subtracted, and shifted around. The 12-day gap between the May 4 closing in Boston and the Chicago opening was necessitated by a major overhaul of the script and the attendant extra rehearsal time. It had become clear that critics and audiences, pre-Chicago, had been jolted by the near-final-curtain suicide of the romantic lead, Danny.

Chicago theatergoers were met with a modified script in which Danny attempts suicide after a dream in which girlfriend Lola – a nightclub singer – has married the doctor who has been courting her. He recovers from his wounds, heads off to San Francisco, but returns a decade later only to learn that Lola never married the doctor, but rather a shoe salesman.

Danny makes no attempt to locate Lola, but, at the final curtain, walks off the stage wallowing in self-pity … still a far cry from the uplifting ending expected by Midwest audiences more attuned to the dramatic formula of Oklahoma!

It is worth noting that Windy City began life as a 1943 play, The Honest Gambler, by Philip Yordan – a play with much the same fundamental storyline as the musical, but with a much happier ending: Danny and Lola marry, have a child, and wind up working at the cigar shop that Danny bought with his gambling winnings.

Morphing into Of Him and Her

In 1944, the play morphed into a musical titled Of Him and Her, but with the suicide installed. Subsequent title changes—first to Danny Boy and then to Windy City—had little, if any, effect on the storyline until the final revision done for Chicago.

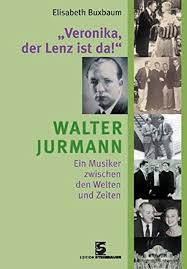

The 2006 biography of Walter Jurmann by Elisabeth Buxbaum. (Photo: Edition Steinbauer)

Almost a decade later, in 1955, Jurmann – still obviously with confidence in the show – prepared yet another script, Heads or Tails, which follows the basic plotline of the earlier versions, but sets the second act in Las Vegas, to which the entire cast has relocated to support Lola, engaged to the doctor, in her new job as a vocal headliner on The Strip. Only Danny hopes that she fails, becomes disenchanted with her doctor fiancé, and returns to him. She is a big hit in her debut but, nevertheless, near the final curtain, bolts from her wedding ceremony and falls into Danny’s arms.

Jurmann registered this version of the script with the Dramatists Guild. There is no evidence to suggest, one way or the other, whether the changes to the storyline were done in collaboration with Philip Yordan (who is still identified as the sole author) or by the composer himself.

Fast forward more than half a century: Jurmann’s widow Yvonne, who, since her husband’s death in 1971, has spent much of her time championing his music both in Europe and in her hometown of Los Angeles, spoke often of his continued fascination with the show long after it closed in Chicago. She talked of his frustration that the show had failed and how he delighted in trying to keep it alive for her by playing excerpts on the piano.

Ohio Light Opera Gets Involved

This CD producer caught wind of her enthusiasm, got caught up in it himself, and mentioned the show to Ohio Light Opera artistic director Steven Daigle, who, for that company, has created performance editions for numerous rare and forgotten operettas. Steven read through the script and instantly became enchanted with the music and lyrics, and fascinated by the gambling/romantic plot (a Guys and Dolls story four years before Guys and Dolls).

As had most of the reviewers back in 1946, he identified some of the weaknesses in the book and set out to revise the script – fleshing out some of the characters, providing back history to some of the subplots, and fashioning a happy ending that, at least for a 1946 musical, seemed to be demanded by the troubled, but sincere, romance of Danny and Lola.

Discussions by Yvonne, over the past few years, with Paul Francis Webster’s son Guy (recently deceased) and by this producer with Guy’s widow Leone and with Philip Yordan’s widow Faith have resulted in enthusiastic endorsements of this CD project, which brings to life this neglected work and the contributions to it by three of the driving forces in mid-20th-century music, theater, and film.

To order the CD via the Operetta Foundation website, click here.