Kurt Gänzl

Kurt of Gerolstein (Blog)

8 October, 2016

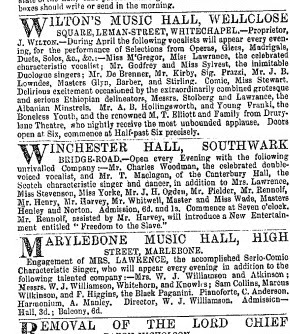

One thing leads to another … Answering various queries, after my 15 years old article on The Black Crook, which tries to debunk the mythology surrounding the production of this so called ‘first American musical’ (it was far, far from it), was re-published recently, I got sidetracked: into other unexplained details concerning that pasticcio leg-show spectacular, details which are glibly repeated by one Broadway website and another. Not to mention Wikipedia.

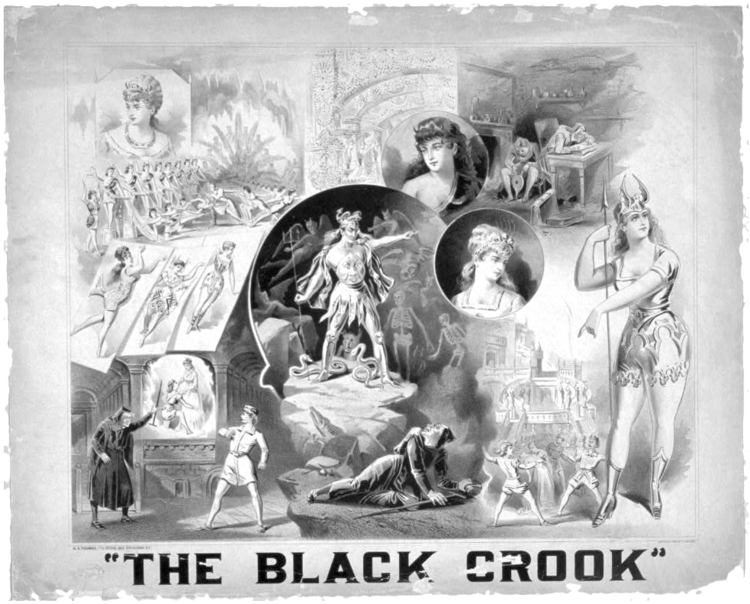

Poster for the original “Black Crook” production.

The most attractive and success-bringing elements of the original production of The Black Crook were, of course, its scenery, its massed troupes of little ‘dancing’ girls and its genuine-star dance soloists (when the advertisements could spell their foreign names correctly), but, somewhere in there, there was some dialogue, lots of incidental and dance music and the odd song.

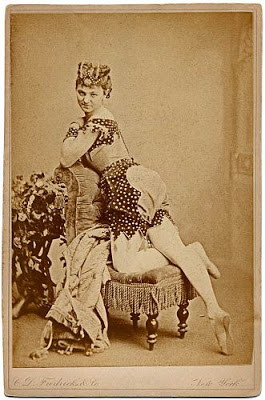

Dancer from “The Black Crook” advertising herself in a ‘shocking’ pose. (Photo: Archive of Kurt Gänzl)

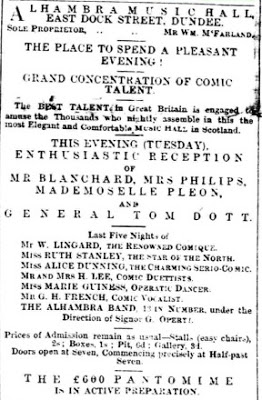

The music. Let’s get the music credit for the show correct. The show was a pasticcio of music old, oldish and made for the occasion. Such new music as was required was – as the bills clearly state, and as was the custom of the time – the work of the conductor, Thomas Baker. The usual formula was ‘the music selected, arranged and composed by …’. Quite who decided (in modern times) to tack the name of Giuseppe Operti on to the credits I know not. Il Signor Operti (‘pianist to His Majesty the King of Sardinia’) was, at the time of the Black Crook’s opening, strumming the keyboard in Dundee, Scotland, at the Alhambra Music Hall.

Announcement for the Alhambra Music Hall in Dundee, Scotland. It mentions Il Signor Operti under “Direction.” (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

Since 1856, he had been living in Britain, where his engagements had included the post of prompter at Drury Lane, playing piano at Holder’s Music Hall, Birmingham, with the Italian opera stars in Dublin, and producing four performances of Verdi’s Macbeth for the Ladies’ Garibaldi Benefit Fund (oh dear! poor King of Sardinia!) at Birmingham Theatre Royal. With himself in the title-role. It was 1869 before he decided that the grass was potentially greener beyond the Atlantic, and headed for New York. I see him first (‘Signor Operti of Europe’) conducting at the new Tammany Hall. Anyway, he stayed in America, worked in mostly similar posts, composing, like Baker, when required, as he had in England, and died in Brooklyn in 1886. And, in between, he took the baton for a Niblo’s ‘version’ of the Black Crook in 1872 (12 February) on which occasion he took a conductor’s privilege of shovelling as much as possible of his own music into the programme, between the dances and the acts (snake-charmer, horse act, monkeys and goats, the Majiltons etc), of what was now a veritable variety show. And, of course, shovelling the original out. ‘Signor G Operti had composed considerable new music for portions of the spectacle’ reported the press. So that is the Signor’s connection with The Black Crook. The bones of the show under the same name anyhow. Five years after the original production, in a very approximate ‘revival’.

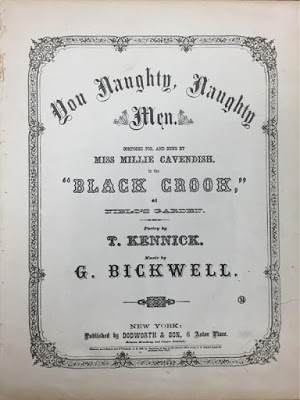

Sheet music cover for “You Naughty, Naughty Men,” a specialty number performed by Miss Millie Cavendish. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

The other name which finds its way into the www music credits is that of George Bickwell. Associated with one Theodore Kennick (words). These two gentlemen were the announced writers of the most popular of the ‘selected and arranged’ part of the score, a song entitled ‘You naughty, naughty men’, sung in the show by the English music-hall artist billed as ‘Millie Cavendish’. I wonder why no one has thought to investigate these three folk, considered by some to be so important to the History of The American Musical Theatre.

‘Millie’ got me into this, so I’ll leave her till last. George and Theodore? Strange, that two writers who turned out such a popular song don’t seem to have written anything else. In fact, they don’t seem to turn up anywhere. I began to suspect that they didn’t exist. That they were ‘authors of convenience’, covering the fact that ‘Millie’ had brought her song, manufactured to her needs, maybe from other folks’ material, from England. But then, I found George. Just one mention. In 1858-9. He was a very (very) minor music-hall pianist in London, and played accompaniments for J H Ogden, on tour. Did he compose or arrange the music for her music-hall act?

A 1858-9 newspaper clipping on J. H. Ogden. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

And what about the words … ? In 1840 (12 May), the Haymarket Theatre produced a version, by Frederick Webster, of Duvert and Lauzanne’s French farce Le Commissaire Extraordinaire, under the title The Place-Hunter. Tom Wrench starred, and Priscilla Horton was the soubrette, Babille, with a song. Called ‘O you naughty, naughty men’.

Priscilla Horton (1818–1895), as Ariel in “The Tempest.” Painted by Daniel Maclise (1806–1870).

Alas, I can’t get at the script to see if the rest of this (uncredited) song is the same, but I shouldn’t be surprised. Anyway, I would say that what one historian labels as an important song in the timeline of American show-songwriting is, in fact, a mish-mash of old English material sailing under fake colours.

‘I puts it to you and I leaves it to you’ as another American show says. And I am willing to be proven wrong. But I bet I’m not.

And now, ‘Millie Cavendish’. Whom the press at one time claimed mendaciously to be ‘of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane’. Here is another person who doesn’t appear to have existed. Well, in spite of the grave in Greenwood Cemetery, King’s, labelled ‘Millie Cavendish, died 23 January 1867’, and a Wikipedia article, she didn’t. And this one I can sort out much better than I can George and the wretched Theodore.

‘Millie’ lived only for the short time she appeared on the Niblo’s stage. But she’d spent fifteen years, in England, as a characteristic vocalist on the music-halls under a different name. She was (either really, or just professionally) Mrs Lawrence. Just that. I have searched and searched for Mrs ? Lawrence and her husband in the public records of the day, but so far with no luck. But I have plenty of sightings of them in action, beginning in Sheffield’s Royal Adelphi Concert Hall in August 1852. Mr L is part of a blackface double-act with one John Stolber (d Cairo 26 November 1869), and Mrs L is doing her serio-comic act. Songs and ‘mimic of men and manners’. Both acts were successful. Lawrence and Stolber ‘the Albanian Minstrels’ played in Germany, Spain, Egypt and doubtless elsewhere as well, until Stolber’s death. Mrs L played first-class halls, often topping the bill. I track her from Sheffield to Rendle’s Hall, Portsea, to Chatham’s Railway Saloon, and in 1855 to London’s Surrey Music Hall, the Middlesex, Holder’s Birmingham, the St Helena Gardens, Jude’s in Dublin the Whitebait, Glasgow, and then – in 1858 – to the daddy of them all, the Canterbury Hall.

1858 newspaper listing. (Photo: Archive Kurt Gänzl)

Wilton’s, the Raglan, Deacon’s, the London Pavilion, the Marylebone and back to the provinces at Hull, Scarborough (‘combines a fine figure, pleasing deportment and a musical voice’), the Manchester Free Trade Hall Monday Pops, Leeds Amphitheatre (‘a great success’) et al. In 1864 she was seen at the Knightsbridge, the Pavilion, the Marylebone, alongside a certain Signor Alberto who would become Alberto Laurence and a well-known New York singing teacher, at the Lansdowne Islington Green, in 1865 she was starred at Holder’s … but she is less in evidence than heretofore. I spy her at the Marylebone in April 1866 … and then comes the trip to America, the invention of ‘Millie’ and her sad death.

Mrs Lawrence (Mr seems to have disappeared off to foreign parts with good pal Stolber some years ago) had had a fine career, and apparently in spite of a handicap. She was an epileptic.

And she was said to have died in her New York digs from a cranial injury suffered during a fit. Some of the newspapers said it was an ‘apoplectic fit’. I suppose some were less charitable. One paper proffered that she had a husband and two children in London. I’ll find them in the end. But first I’ve got to find out what they were called!

So, there we are. A little more clarification, the demystification of a few more folk, but a good deal still to find. But if I publish this now, maybe someone else can lay hands on some proof. Find a copy of The Place-Hunter. Find some first names for the Lawrences (is he the George ‘singer and dancer’ in the 1861 census?). Find … well, anything relevant.

Poster for the “Black Crook” production 1866.

PS: I can’t let these folk go. And I have found a little more George. It appears that his name was rightly George Day Backwell, son of Devonshire musician Joseph Lewis Backwell and his wife Helen Day. His younger brother Joseph Day B was also a muso. And the reason that he didn’t write any more songs, is that he couldn’t. Round about the opening night of The Black Crook - maybe even before, I hope after - George died, at Brentford, at the age of 34. Brother Joseph had died at 27. Father died in 1867. I hope George’s widow/partner collected the royalties. Or, dreadful thought, was Bickwell-Backwell listed as the composer of the song because he was dead … only a death certificate would tell for sure.

To read the original article on Kurt Gänzl’s Gerolstein blog, click here. And for part 1 of Kurt Gänzl’s Black Crook essay, from 2001, click here.

This information is very valuable. Thank you!