Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

20 December, 2018

Sometimes you read an operetta essay that deeply disturbs you – not because it is badly written or full of errors, but because it takes time for the information to sink in and work its way into your brain. Such an essay is Bonnie Gordon’s “Operetta and Display,” published in English in 2015 in Kunst der Oberfläche: Operette zwischen Bravour und Banalität. The disturbing aspect, for me, was her comparison of operetta divas such as the fictional Nana in the Émil Zola novel with colonial and racial displays at the universal exhibitions in Paris, and Gordon’s equation of Zola’s “Blonde Venus” with Hortense Schneider as Venus’ daughter Helen of Troy and with Sara Baartman, the famed “Hottentot Venus” whose body was dissected after her death in 1815, so that her remains (including her genitals!) could be exhibited at the Musée de l’Homme.

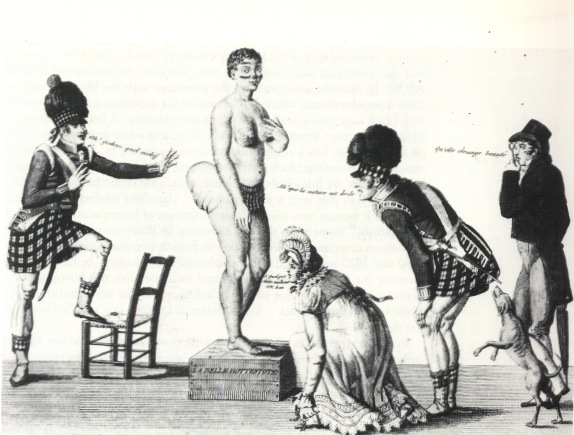

19th century French print “La Belle Hottentot” of Sara Baartman.

According to Bonnie Gordon’s argument, Zola’s “Blonde Venus” is characterized by an “excessive and dangerous sexuality” that makes her an immediate sensation in the Paris operetta world of the Théâtre des Varietés in the 1860s (it’s the same time and theater where La Belle Hélène premiered with “La Snédèr” in the title role). Nana is an object of desire, and because she comes from a poor working class background and needs money to survive, she “descends” into the demimonde class, just like the heroine in Zola’s Thérèse Raqin who does so because of her mother’s African blood: “Both women fall into paths of destruction because of their inherently degenerate genealogies.”

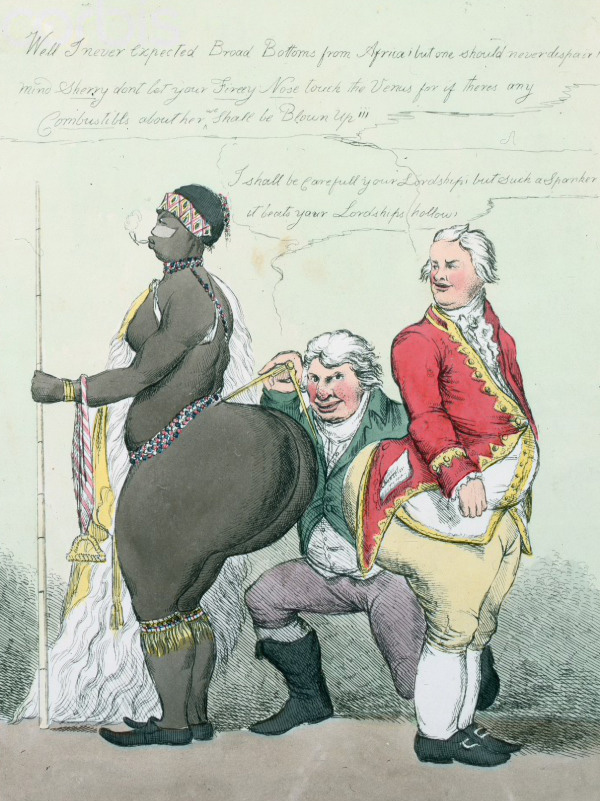

“A Pair of Broad Bottoms”: 1810 caricature of Sara Baartman by William Heath.

Gordon argues that 19th century French imagination projected images of Venus onto black female bodies as part of a cultural effort to naturalize the supposed essential licentiousness of the black female body: “Nude black women embodied the ultimate difference – the sexualized savage.”

Is Nana a sexualized savage, too? And if she is, does this apply to Hortense Schneider and other famous 19th century stars as well? Is such savagery what high class male operetta goers longed for when they attended Offenbach and Hervé performances? In a different text Zola writes: “The pleasure-seekers used to meet here [i.e. the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, Offenbach's 'other' stage]. The little theatre in the Passage Choiseul had the reputation of a distinguished, shady establishment where it was the done thing to be seen. The vice of a whole epoch passed through it – I mean the vice in gloves and diamonds.”

Charicature of Offenbach’s stage, the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens.

In his shows Offenbach puts decadence and promiscuity on display, and nowhere more so than with the notorious “infernal gallop” from Orphée aus enfers. So Gordon asks if the leading female characters in these shows were empowered and emancipated? “The story becomes more complicated if the conversation moves beyond the operetta stage to the off stage lives, reputations, and perceptions of female operetta stars. The performative power and erotic agency that female singers claimed earned them distrust and disgust.” They were seen as “erotic sorceresses” who bewitched audiences with their “voluptuous gestures” – including the Khedive of Egypt who built a special theater in Cairo to have Miss Schneider perform Helena.

Gustave Doré’s vision of the „Galop infernal“, as seen 1858 in Paris.

The leading Offenbach ladies all danced the cancan, and made a splash doing so. Frederic Loliée writes about Lise Tautin as Eurydice: “The applause was greater still when she danced a wild Cancan, which was a source of envy to some of the most daring professionals of Mabille, the more so as she wore the shortest of skirts.” Richard Wagner wrote: “In the Parisian cancan the immediate act of procreation is symbolically consummated. How any artistic element can enter into the thing, seems difficult to comprehend.”

Lise Tautin in 1858.

Such statements make it easy to understand why many 19th century critics thought Offenbach’s musical theater works had no “artistic element” and were “vulgar” and “dangerous” for society. An evaluation shared by Zola in Nana.

What Bonnie Gordon does in her essay is ask if we should (and could) compare the way Offenbach’s heroines on and off stage were treated in the 19th century to the way black women were/are treated and seen? “Operetta might be a productive site in which to consider social relations that determine what counted as black and what didn’t,” writes the University of Virginia professor.

“Attempts to control the black body, such as the display of the Hottentot Venus or the labeling of Josephine Baker as primitive, represent attempts to control the black female body as part of a process of managing the white female body and reifying the degenerating white male body. Thinking about the intersection of race and Operetta makes the business seem less empowering for women and more pernicious than a genre of topsy-turvey kitsch.”

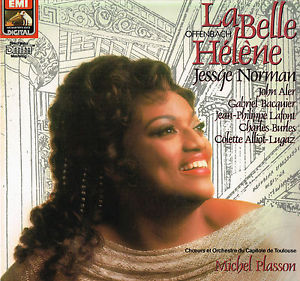

Jessye Norman on the cover of the 1985 recording of “La Belle Hélène.” (Photo: EMI Music France)

Those are the last words of Gordon’s essay, which cuts off rather abruptly, without going into a deeper Offenbach discussion. But maybe that’s why Gordon’s statements keep resonating in me, because I am still trying to make sense of them and find out where they might lead.

What happens when you apply Gordon’s “Black Venus” and “Hottentot Venus” perspective to a famous Belle Hélène recording such as the EMI version starring Jessye Norman? What if we don’t listen to that performance in a “color blind” way but specifically ask what it means to have an African-American soprano as the libidinous queen of Troy who suffers because “La main de la fatalité qui pèse sur moi”?

Ngako Keuni in “Dream Girls” style at the UdK production of “Die schöne Helena,” 2018. (Photo: Madis Nurms)

These thoughts came back to me as I watched a Belle Hélène performance last week in which Ngako Keuni briefly slipped into the role of Venus in Dream Girls style – for the “apple aria” sung by Prince Paris. How empowering was operetta, or rather, how empowering can it be today for black performers, for PoC, and for everyone else?

Bonnie Gordon doesn’t give final answers, she just asks a lot of questions and quotes many amazing historic sources, among them Cora Pearl’s The Erotic Memoirs of a Passionate Woman, to use the 1890 English title. (It’s a book I have never – ever! – seen quoted in any Offenbach biography to date, even though Miss Pearl appeared briefly in an Orphée production and was a regular in Offenbach- Morny-Napoleon III circles.)

1980s cover of a re-print of Cora Pearl’s Memoires.

Bonnie Gordon asks if all singers such as Tautin, Pearl and Schneider are rightfully “darlings of feminist musicology,” whether they really “remind us that male composers do not completely dominate the theater” and that “female singers have always had a performative power that flies in the face of the hegemonic male gaze”? That’s certainly a question to ponder on. Also Gordon’s claim: “What in Operetta is not about Gender and the Body?”

Indeed, that is one of the central aspects when dealing with the genre. Certainly if you focus on Offenbach; which was clear already when Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters came out, years ago, with so many historic quotes to digest that Offenbach research has been busy doing so till today.

With such gender and body discussions at the back of my mind, and with the “Black Venus” controversy rumbling in my brain after watching Belle Hélène recently, I found it all the more astonishing that the latest German language Offenbach books by Ralf-Olivier Schwarz and Heiko Schon shy away from these points. Mr. Schon admittedly mentions them in passing, but Mr. Schwarz in his full fledged biography pretends all of these debates have never happened, even though he quotes Zola’s Nana (but without the nude performance and without the brothel section, and without the respective quotes from Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters that confirm Zola’s fiction with real-life examples).

I guess these are the two extremes of current Offenbach research that mark the terrain for the 2019 celebrations. I wonder if Bonnie Gordon will publish another Offenbach and/or operetta essay in the context of the bicentenary of Offenbach’s birth.

I certainly would love to read it. And I would certainly love to hear more about the intersection of race and operetta – if La Belle Hélène is a good starting point for this, then that’s fine with me.

This is fascinating! I’m hoping for more discussions on race and gender within operetta in the future!

The Cora Pearl memoirs have not been cited by any reputable historian because they are a fabrication by a 20th-century British author.