Richard C. Norton

Operetta Research Center

1 September, 2006

The overwhelming and instant success of Erik Charell’s operetta spectacle Im weißen Rössl at Berlin’s Großes Schauspielhaus (the so-called “Theater der 5000”[1]) on 8 November 1930 sparked immediate interest from foreign producers. Historically speaking, German operette typically ventured first from Berlin to Vienna (and vice versa) before reaching Hungary, France, England and the United States.

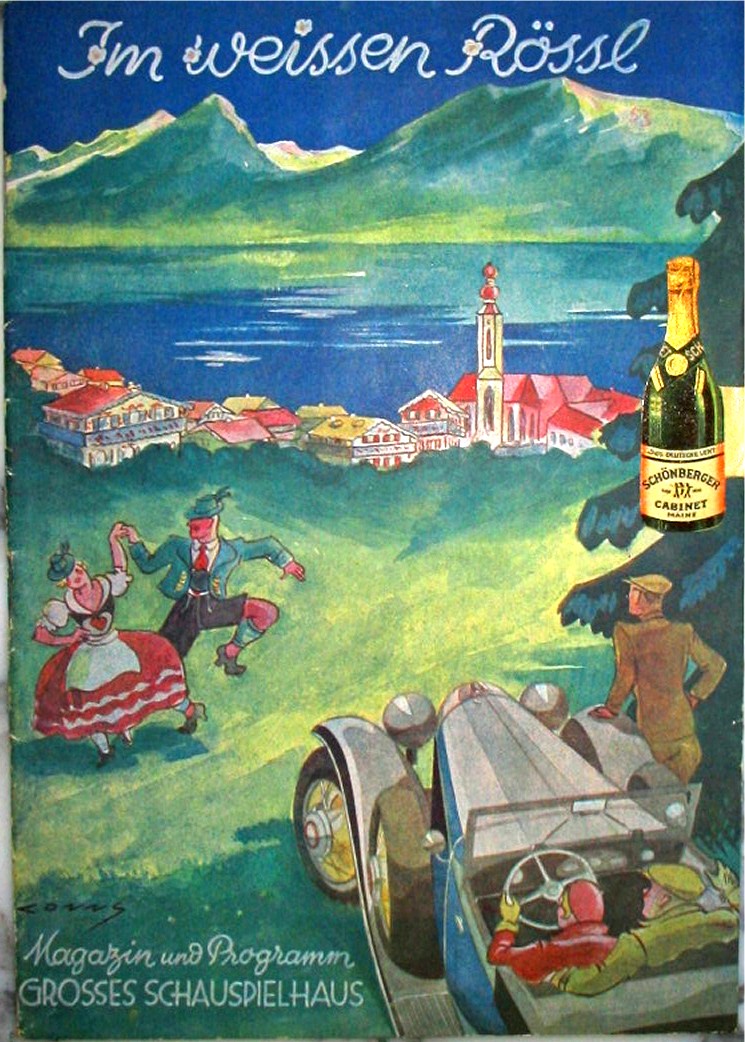

Souvenir broschure of the original 1930 Berlin production of “Im weißen Rössl”.

Ever since the 1880’s, when the Viennese operettes of Johann Strauss, Franz von Suppé and Karl Millöcker became internationally popular, and especially following Franz Lehàr’s worldwide phenomenon Die lustige Witwe which became The Merry Widow in London’s West End (8 June 1907, Daly’s 778 performances) and on Broadway (21 October 1907, New Amsterdam, 416 performances), American and English impresarios maintained a network of local representatives, agents and correspondents for the purposes of acquiring and licensing Berlin and Viennese operette for English language adaptation and production. The foremost American practitioners of this trans-Atlantic business were the Messrs. Shubert, brothers Lee and J.J., whose revisions of Walter Kollo’s Wie einst im Mai andHeinrich Berté’sDas Dreimäderlhaus, became American cash cows under the titles Maytime and Blossom Time. Often derided by the critics but beloved by audiences, the Messrs. Shubert proved equally adept at producing revue and operetta, less so with musical comedy. Following the Messrs. Shubert’s success with Eduard Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda as Caroline, Emmerich Kàlmàn’s Gräfin Mariza as Countess Maritza, and his Zirkusprinzessin as The Circus Princess, it is not surprising to find Kàlmàn invited to co-compose an altogether new show directly for Broadway, with star librettist Oscar Hammerstein II (who wrote the legendary musical Show Boat simultaneously); their collaboration resulted in the premiere of Golden Dawn in 1927, a voodoo-musical/operetta set in Africa, filmed by Hollywood with Vivienne Segal in the lead in 1930. – On the other side of the Atlantic, in Berlin and Vienna, American jazz became the derniere crie, also in operetta and especially in revues. „Ein neues Tempo rannte gegen den Wiener Walzer an“, schreibt Paul Markus über jene Jahre in seinem Buch Und der Himmel hängt voller Geigen:

Trillerpfeifen und Autohupen und Kuhglocken klangen aus den Orchestern. Der argentinische Tango, vor dem Krieg noch als ‚unanständig’ verfemt, war mit einem Male salonfähig […], und die jungen Leute, die jahrelang in den Schützengräben ihr Vergnügen entbehrt hatten, hupften in den abgehackten Synkopen des Foxtrotts. Die Welt drehte sich nicht mehr im Dreivierteltakt, sondern schob, hüpfte und lief beim Tanz.[2]

In his very first own revue An Alle, Erik Charell introduced Berlin in 1923 to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The rest of the score, which contained songs by Irving Berlin (“Alexander’s Ragtime Band”) and other Broadway giants, was arranged and supervised by Ralph Benatzky, Charell’s musical collaborator from then onwards. Benatzky was particularly good in adapting American style music for German needs, demonstrating a great feeling for the new rhythms which he also included in his other work, created without Charell. Their joint effort Im weißen Rössl was to be the last of the great Schauspielhaus revue operettas, in many ways their opus magnum. It too had a jazz band in the orchestra and brilliantly juxtaposed Austrian sounds played by a Schrammel Kapelle onstage with American beats coming from the orchestra pit. The BZ am Mittag wrote:

(D)as Lokalkolorit wird sozusagen synkopiert von der Internationalität der Girls und Boys, die beweisen sollen, daß auch St. Wolfgang nicht außer der Welt liegt. Ihre Tänze sind das fließende Band, das die Handlung aufrollt, heranträgt, in Takte und Akte teilt. (…) Der Rhythmus, die Zweiteilung setzt sich bis ins Orchester fort, dessen Linke Jazz, dessen radikale Rechte Zither und Laute sind, Heimwehrlaute unter Steirerhut und Hahnenschwanz.[3]

With such international sounds, it is hardly surprising that the Rössl went on a very successful international tour. After Germany, Austria, Italy and France it conquered the English speaking world with two productions which were both newly created and directed by Erik Charell himself. Analyzing them, one understands what he wanted the Rössl to be and how he wanted it performed, which is very different to what we today consider to be the Weiße Rössl. Making this survey even more fascinating and important.

The “Tiroler Gruppe” as Charell originally used them in “Für Dich” 1925.

The German Conquest: The White Horse Inn in London

In late 1930, shortly after the Berlin premiere of Im weißen Rössl, English impresario Sir Oswald Stoll, Managing Director of the London Coliseum[4], was seeking a musical spectacle capable of filling this spacious 2200-seat house located just north of Trafalgar Square, in an altogether new policy, a reprieve from the house’s previous diet of variety[5]. Theatre historian Felix Barker in his volume The House That Stoll Built: The Story of the Coliseum Theatre, outlined the strategic £40,000 risk that Stoll undertook to change the theatre’s performance policy. Stoll chose Harry Graham, London’s most experienced adaptor of German operette[6], for the assignment of British book and lyrics. Seventeen years earlier, Graham had adapted Jean Gilbert’s Die Kino-Königin as The Cinema Star for West End eyes and ears. His British adaptations of Jacobi’s Szibill from Budapest, Stolz’s Der Tanz ins Glück, Der Fürst von Pappenheim, Gilbert’s Katja die Tänzerin, Oscar Straus’ Die Perlen der Cleopatra, and Franz Lehàr’s Der blaue Mazur had followed throughout the 1920s. Graham was at the peak of his career in 1931; including the forthcoming Das Land des Lächelns, Viktoria und ihr Husar (Paul Abraham) and Casanova (Benatzky/Johann Strauss) this same year, White Horse Inn would be Graham’s longest-running hit of all. Working with uncommon haste and skill, librettist Harry Graham adapted the original German libretto and lyrics for English ears, and White Horse Inn opened exactly five months later in London on 8 April 1931.

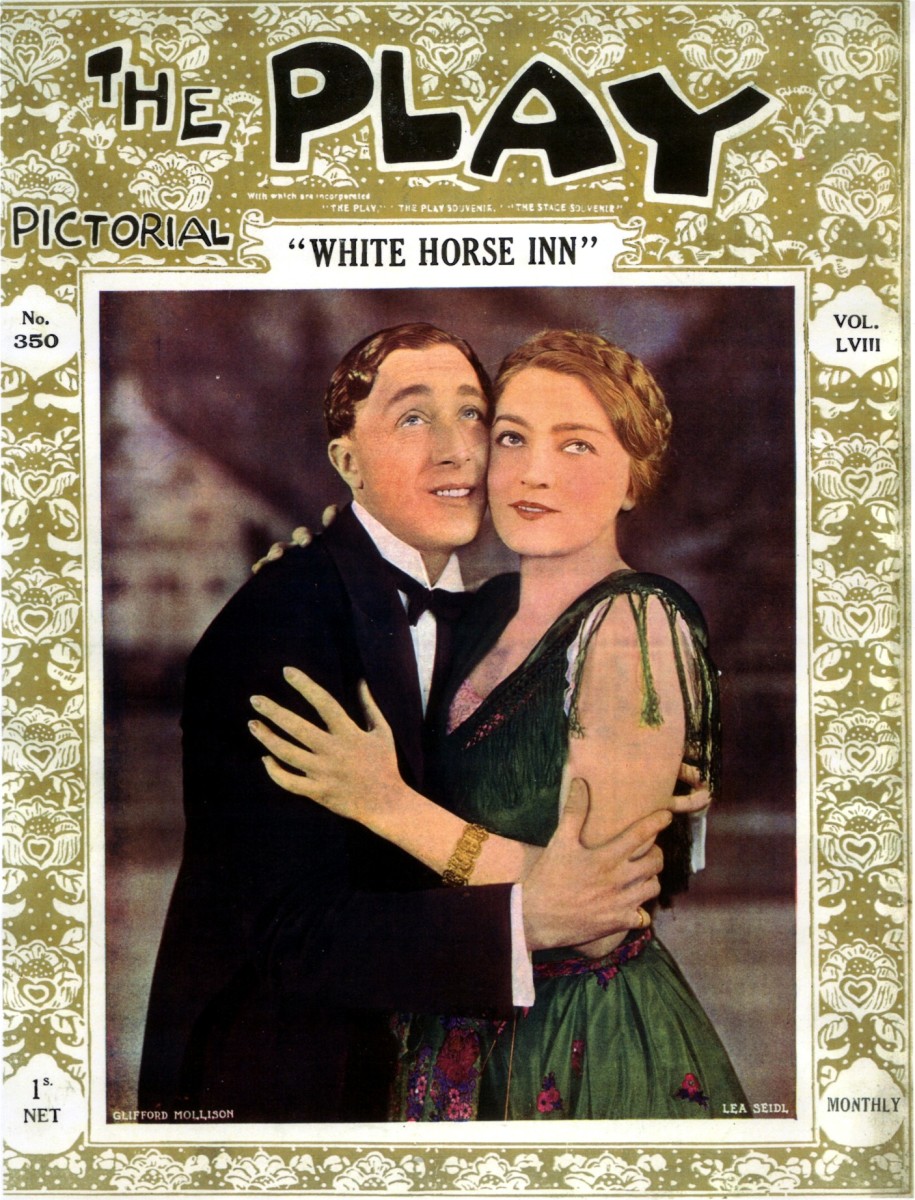

Souvenir broschure for the London production starring Lea Seidl.

This was no doubt possible only because Stoll retained the entire German production team, Erik Charell as conceiver and director, Hans Müller as its original author, Ernst Stern as the production designer, and Max Rivers for dances. Another import from Berlin was the female star Lea Seidl as Josepha. She had been the famous “Marie von der Haller Revue,” and was thus the star of Charell’s greatest competitor in the field of revue – Herman Haller. His theater, the Admiralspalast, stood on the opposite side of the Spree River in Berlin, across from Charell’s temple, the Grosses Schauspielhaus. Choosing Seidl for his production meant casting a decidedly naughty, frivolous woman as the Rössl proprietress, a representative of Berlin’s Roaring Twenties, a reckless “Sally Bowles” of operetta. Thus Charell set the tone for his whole London enterprise, just he had when casting Camilla Spira in Berlin, of which the press noted, she is “fesch, blond, gsund, salzkammergut, eine junge Hansi Niese“.[7]

While the basic narrative structure of the German original remained intact, several characters and much of the topical humor was Anglicized for local tastes. The central romantic duo, Josepha Voglhuber (sic) and Leopold Brandmayer, remained for the most part unchanged. For London audiences, Wilhelm Giesecke, the comic but irascible Berlin manufacturer of men’s underwear, became John Ebenezer Grinkle, a choleric, paunchy Oldham[8] manufacturer of ladies’ patent underwear, the “Apollo” combination, and one-piece “Vestinicks” that buttons up the front. Author Harry Graham was unable to find a precise foreign equivalent for Gieseke. His insistence upon speaking Berlin dialect reflects his great pride, as it is both the dialect of the German capital and the German Kaiser. Ironically, what sounds provincial in English (i.e. speaking dialect), is meant to sound vastly superior in the German original, if not downright arrogant! Giesecke/Grinkle’s nemesis, Smith of Hammersmith, purveyor of the “Hercules” combination, and one piece “Shirtopants” which buttons up the back, has dispatched his son, Sigismund Smith (formerly Sigismund Sülzheimer), to the White Horse Inn to negotiate a settlement between the rival manufacturers. Renaming Sülzheimer as Smith sacrifices the recognizable Jewish joke. Not only did Giesecke feel superior by speaking Berlin dialect, he also calls Sülzheimer a “Shylock,” a term of open disparagement which makes their ultimate reconciliation only funnier. All of this was abandoned for a more generic, gentler contrast of big city vs. provincial behaviors. Giesecke’s daughter Ottilie was renamed Ottoline for London audiences. Otto Siedler, the dapper city lawyer for whom our heroine Josepha pines, became Valentine Sutton; it is he who suggests the commercial marriage “union” between Ottiline and Sigismund, thereby cornering the “underwear market of the world.”

For its London debut, Charell and Stoll chose stalwart and proven musical comedy/operetta talents, none of whom could compete with the spectacle of the show itself. Clifford Mollison, cast as Leopold, worked first as a dramatic actor in the West End before appearing as Adolar von Sprintz in London’s The Blue Mazurka (Lehár’s Der blaue Mazur) in 1927, after which he committed to musicals almost exclusively: Rodgers & Hart’s The Girl Friend , Lucky Girl, Here Comes the Bride, Nippy. His portrayal of Leopold is a decidedly British affair, turning the head waiter into a sort “Jeeves” butler (the famous P.G. Wodehouse character), which offers a whole set of new comic possibilities. (The Sunday Times noted that “Mr. Clifford Mollison (…) sticks manfully to the English tradition of musical comedy”.[9])

Lea Seidl, as noted above, also originated Lehár’s Friederike in London in September 1930. She remained in the UK and became a naturalized British citizen, starring in a revival of A Waltz Dream (Ein Walzertraum), Dancing City and No Sky So Blue following her success in a full year’s run of White Horse Inn. The Observer remarked on Lea Seidl:

Yet out of the welter emerges such charming personal achievements as Miss Seidl’s innkeeper (…) a performance so clear in outline, sympathetic in characterisation and charmingly sung, that one is tempted to start instanter for these Tyrolean heights.[10]

Jack Barty, cast as John Ebenezer Ginkle, was first a music hall comedian and Variety artist, appearing in Christmas pantomimes such as The Sleeping Beauty and The Queen of Hearts. Ginkle’s daughter, Ottoline, was played by Rita Page, a singing/dancing soubrette and veteran of featured roles in dozens of West End musicals.[11] In the role of Ottoline’s romantic partner, Valentine Sutton, Bruce Carfax performed much the dashingly roguish hero he had played before in The Maid of the Mountains 1930 revival, Sons o’ Guns, The Blue Mazur, and would continue to play (as Paris) in Offenbach’s Helen, Jerome Kern’s The Cat and the Fiddle and Music in the Air.

Acquatic exercises in London.

Frederick Leister, given the choice cameo as The Emperor, lent the evening a note of gravitas as the production’s sole experienced non-musical dramatic actor. Cast as Sigismund Smith, George Gee, the popular comic sidekick in dozens of British musicals, segued effortlessly from similar roles in London’s Rio Rita, Hold Everything, Virginia, The Girl Friend, and Australia’s Tell Me More and the title role in the Eddie Cantor vehicle Kid Boots.

An examination today of Harry Graham’s libretto suggests that his text is decidedly old-fashioned, in the declamatory style typical of English operetta of the 1910s and 1920s, but it does stick closely to the German original. Instead of naughty wit or cosmopolitan charm, the characters express themselves broadly with hearty cheer and loads of exclamation points. For example, Karl and Leopold speak as Josepha makes her first entrance:

Karl: Take my advice, Herr Leopold, as man to man. Sending roses anonymously every day to Frau Josepha – it’s madness. Women will be the ruin of us chaps.

Leopold: One woman, yes! Every time she looks at me with her lovely eyes… every time she speaks to me with her silvery voice… I forget everything.

Josepha (enters, with her back to the audience, angrily): Himmel donnerwetter noch ein mal.

Leopold: That silvery voice!

Josepha: Leopold! What do we charge for goulash?

Leopold (gazing at her in dreamy admiration): When you ask me things like that, I forget everything.

Josepha: Naturally! Blockhead![12]

The show’s first big hit song, the duet between Leopold and Josepha (“Es muss was Wunderbares sein!”) became “It Would Be Wonderful indeed, if you could love me.” A straightforward and adequate translation, but when indigenous Berlin humor pops up, Graham has difficulty finding any English equivalent. The hilariously funny double-meaning parody chorus of the Dairymaids (“Eine Kuh, so wie du, ist das Schönste auf der Welt!”), become merely plain and dull as in “Happy Cows” sung by the Dairymaids:

Happy cows, as you browse,

Naught can rouse you from your dreams,

And although, as we know,

Life is slow, how safe it seems.

All you do is to moo

And to chew the new-mown hay;

It’s so calm on the farm

And no harm can come your way.[13]

Stolz’ slow-fox duet for the secondary lovers, Otto Siedler/Valentine Sutton and Ottilie/Ottoline, “Die ganze Welt ist himmelblau” became “Your Eyes.” Graham dispensed with Granichstaedten’s appeal from Leopold to Josepha (“Zuschau’n kann I net”) and replaced it with Stolz’ hit song “Adieu, mein kleiner Gardeoffizier” (from the film Das Lied ist aus) which in English became “Good-Bye,” and the show’s unexpected hit. Even though it stayed in nearly all later English language versions of the White Horse Inn, it was never used for German version, possibly because the original German lyrics are so well known, that changing them to fit the story (as was done in London) seemed impossible. The success of this one song is responsible for Robert Stolz’s name on the cover of all English language piano scores of the Rössl, in equally large letters as the name of Ralph Benatzky.

Ottilie/Ottoline and Otto Siedler/Valentine Sutton’s second duet (“Es ist wohl nicht das letzte Mal”) was likewise replaced by a Stolz song “You Too” (“Auch du wirst mich einmal betrügen”). Giesecke/Ginkle and Josepha’s rousing paean to alpine life “Im Salzkammergut, da kann man gut lustig sein!” was translated simply as “Salzkammergut” replete with thigh-slapping and clog-dance ensemble, a showstopper. Lea Seidl as Josepha was given an all new Act 2 solo “Why Should We Cry for the Moon,” prior to the Act 2 Finale. In Act 3, the Emperor’s kind words of advice to Josepha (“’s ist einmal im Leben so”) became the gentle “In This Fickle World of Ours.” Other songs, “Im Weissen Rössl am Wolfgangsee” (as “The White Horse Inn”), “Und als der Herrgott Mai gemacht” (as “Fairies”), Stolz’ “Mein Liebeslied muss ein Walzer sein” (as “My Song of Love”) hewed more closely to their Berlin originals, though the decicely naughty humor of some Robert Gilbert lyrics is somewhat lost.

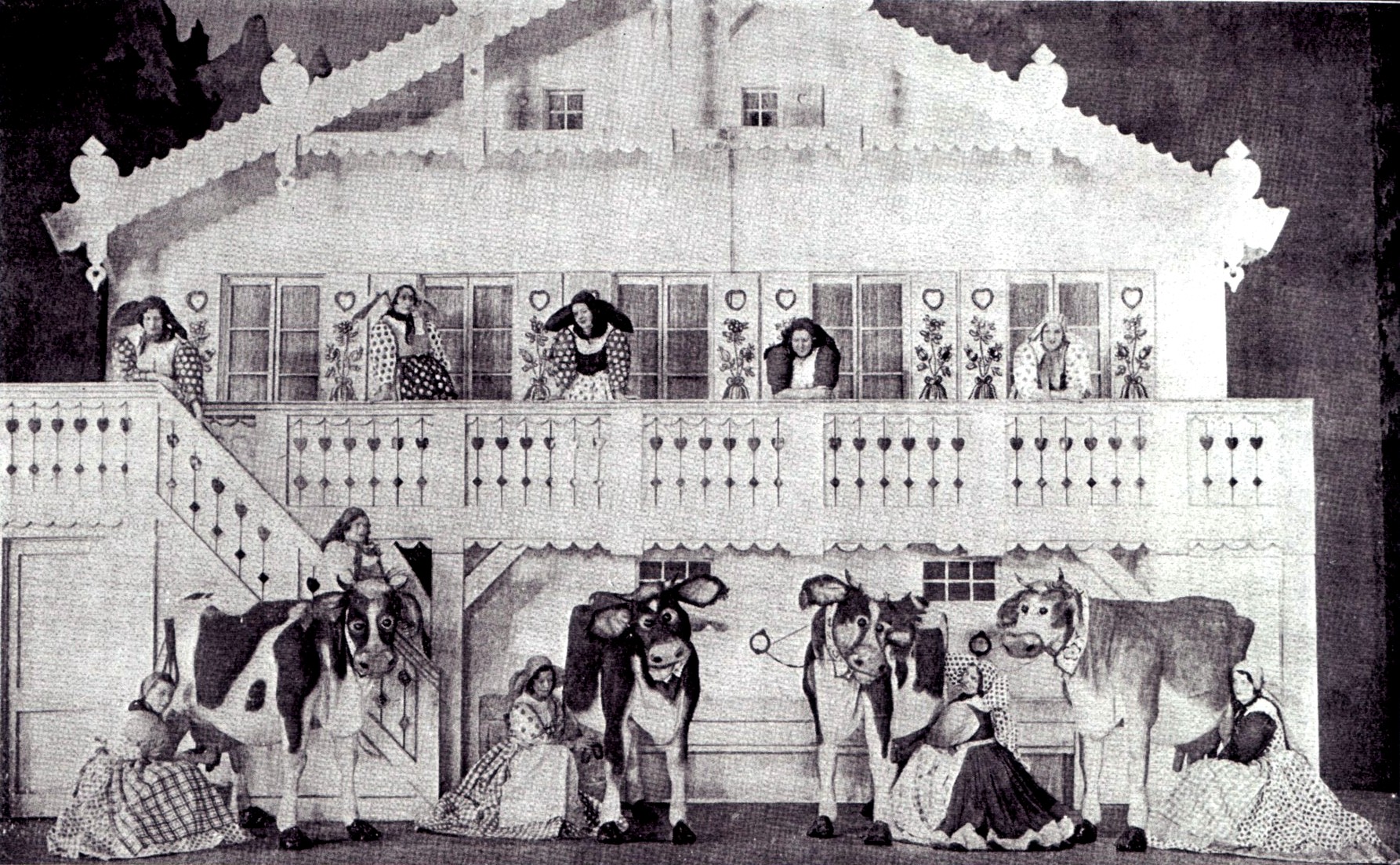

The cow shed scene from the London production.

It seems that the English could not find an equivalent for “Und als der Herrgott Mai gemacht, da hab’ ich es ihr beigebracht. Ein Vöglein hat gepfiffen, da hat sie es begriffen”. Oral sex was obviously not something to sing about in Great Britain 1931.

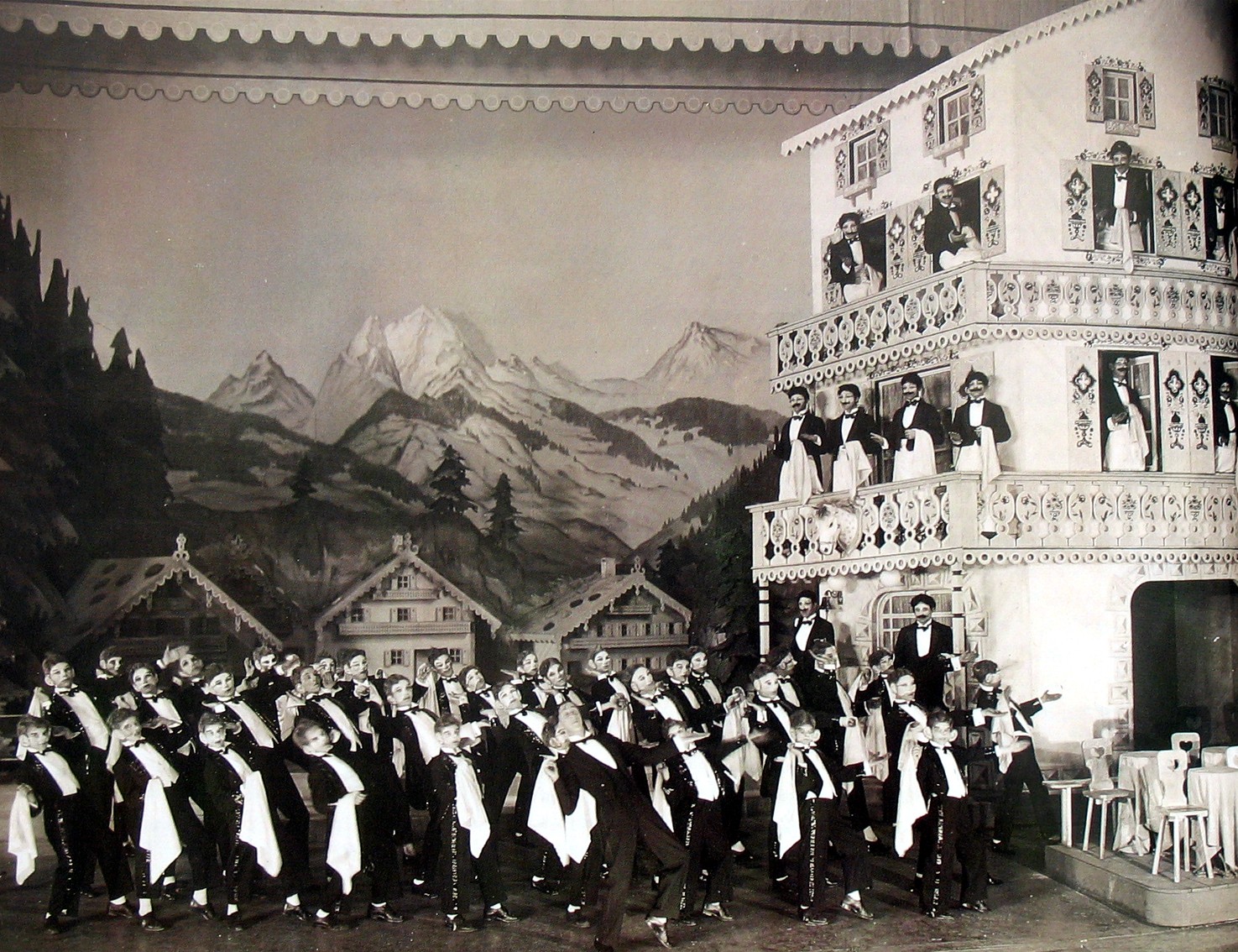

Oswald Stoll was intent upon retaining as many of the production elements which made Charell’s Berlin production a success. The façade of the London Coliseum was adorned with tyrolean green, blue, red and white architectural detail. The sheer spectacle of the cast size, enormous “Im weissen Rössl” set with its windows and balconies, the view of the Austrian Alps beyond, the arrival of tourists by boat, the train, the lake, the rain finale to Act 1, the innumerable (fake) cows, the procession of live animals, the athletic male ensemble in their authentic “slap dance,” combined with the catchy songs and gusty humor to make a popular entertainment of broad commercial appeal. Its pre-1914 Austrian setting celebrated a bucolic, innocent era just before the great world war, economic depression and political upheavals, yet well within the immediate memory of many theatre-goers who yearned for simpler, safer times. At the same time, the music with its jazz band integrated into the orchestra, the big revue-style choreography and the ultra-modern stage effects gave it enough of a contemporary touch to prevent White Horse Inn from looking old-fashioned and stuffy.

Lea Seidl demonstrating how to properly dress and dance in an Alpine setting.

Stoll’s attraction, billed in its published sheet music as a “Musical Play” and in the daily newspapers as a “Play with Music and Dance”, was performed twice daily at 2:30 and 8:15 from Monday to Saturday, for a grueling 12–performance week. Note the absence of the dread word “operetta”! With the advent of talking films, London stage managements were attempting to match the challenge of the cinema, both in terms of a twice-daily performance schedule and sheer visual spectacle. Charell’s advantage: Where cinema could offer only black & white, White Horse Inn had brilliant color on stage and sets in 3-D! Stoll’s decision to play a 12-performance week was a nod to the expectations of the Coliseum’s traditional audience, but declining weekday attendance necessitated a premature closing. Had the White Horse Inn played a traditional 8-performance week, it might reasonably have run as long as Chu Chin Chow, Maid of the Mountains or Me and My Girl, all of which attained runs of nearly 4 years.[14]At its peak, White Horse Inn was grossing over $40,000, more than double any other musical attraction in London West End.[15]

From London to the Provinces, Australia and South Africa

Prospective American audiences, in particular the New York theatre-goers who read the New York Times, were well acquainted with the work of Erik Charell despite the fact that his shows had yet to be seen in America. The New York Times’ Berlin correspondent C. Hooper Trask filed frequent accounts of the popular Berlin theatre scene, in particular Charell’s productions of Casanova, Die drei Musketiere and Im weißen Rössl.[16] The London premiere of White Horse Inn was also duly noted in the New York Times on 27 April 1931:

It requires 250 people and a revolving stage to conduct a love affair in the Alps. Such is the moral lesson for tourists in ‘White Horse Inn’, an opulent and be-yodeled operetta by Erik Charell, which Sir Oswald Stoll is presenting on a colossal scale.[17]

The London reviews amply rewarded Stoll for his courage. G.W.B. in the newspaper The Era writes, that every adjective has already been used to describe White Horse Inn, and one can only repeat “magnificent,” “wonderful,” “dazzling,” “glorious”, and the favorite one of all, “kolossal,” at the same time realizing how “inadequate words look in cold print.”[18] H.H. in The Observer stated:

One’s immediate reactions blend awe with pleasure, and the impressions that remain are like a dream such as might trouble the journey home from narrowly escaped avalanches and Baedecker gone-mad. Yet it is an experience not to be missed.[19]

The hit songs from the score were widely sung and recorded by the popular bands, Jack Hylton and the New Mayfair Orchestra (HMV), Ray Noble (HMV), Debroy Somers (Regal), Jack Payne (Columbia), Jay Wilbur (Imperial), Rolando (Edison Bell), the vocal selection was published by Chappell & Co, Ltd. Vocal selections were recorded by both HMV and Columbia, but, unusual for a hit show of its day, no Original Cast Album was made. Perhaps the lack of stars in the leading roles was the reason. Following a run of nearly a year, Stoll sub-licensed White Horse Inn to his younger protegé Prince Littler, its physical production and ensemble were cut down for touring purposes, and it was seen throughout the 1933, ‘34 and ‘35 seasons in Manchester, Birmingham, Nottingham, Liverpool and other major venues. Australia picked up on the London success and J. C. Williamson Ltd., the leading local producer, mounted its own version in Sydney (31 May 1934, Theatre Royal) and Melbourne (28 July 1934, Her Majesty’s) followed by a continental tour, becoming a huge favorite for decades to come. St. Wolfgang, the Salzkammergut, the White Horse Inn et al. afforded audiences “down under” a touristic adventure and visual feast they would otherwise be unlikely to explore in person. Williamson sent its Australian tour on to South Africa, where it played Durban (29 January 1935), with Nita Croft starred as Josepha, and Bruce Anderson as Leopold.

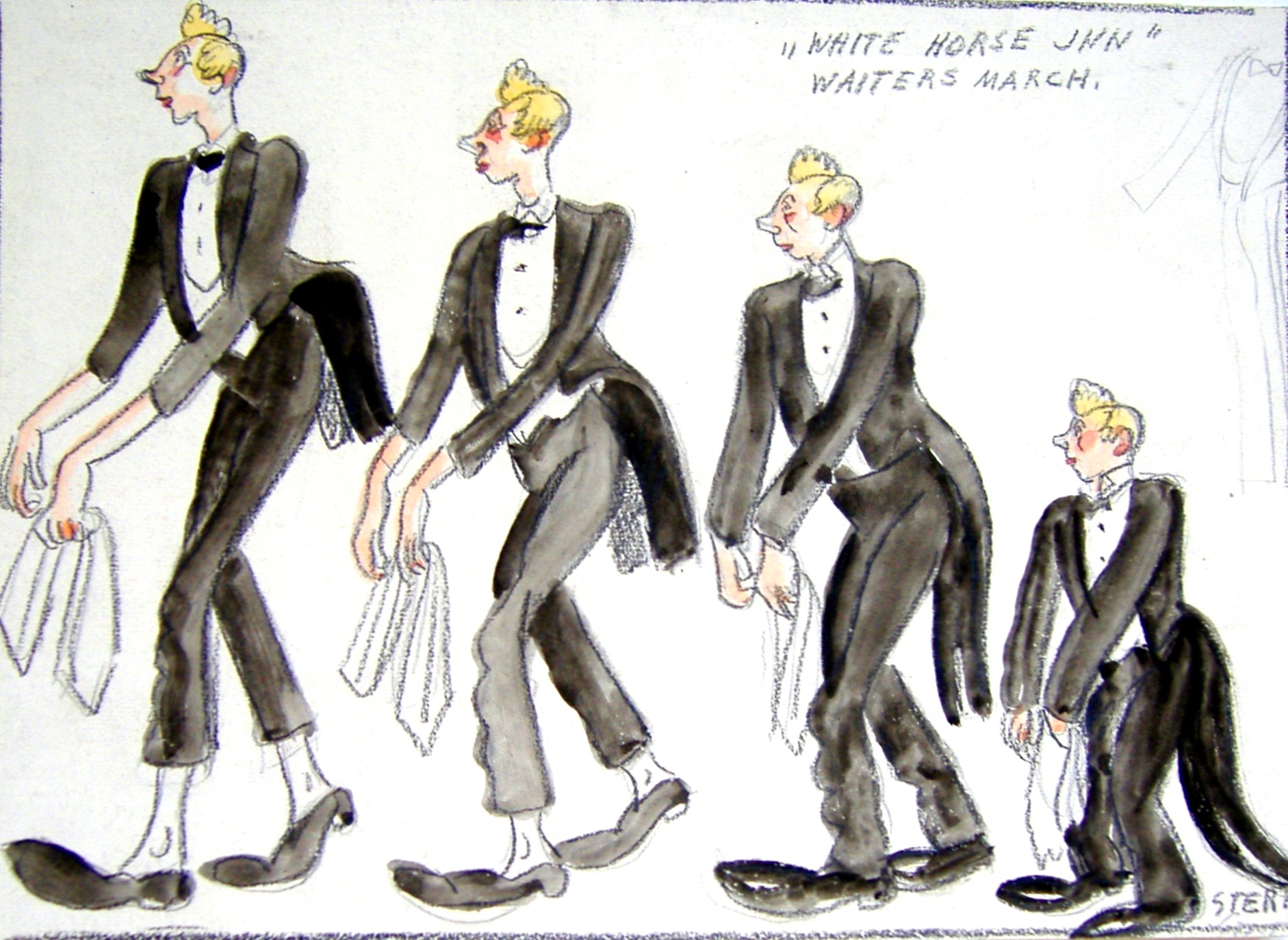

Waiters on parade: the grand marching scene from London, 1931.

The White Horse Inn became an enduring staple of the British musical theatre repertoire. Nine years later, at the outset of World War II, Prince Littler revived White Horse Inn at the Coliseum 20 March 1940 for 270 performances. London’s Empress Hall hosted the show “On Ice” in 1953, which then toured in 1954/55. Regional professional and amateur productions had been licensed by the Coliseum Syndicate, but with the demise of Oswald Stoll, such performance rights were assigned in 1957 to Samuel French,[20] who commissioned Eric Maschwitz and Bernard Grün[21] to revise the text for smaller productions. According to musical theatre authority Kurt Gänzl, the White Horse Inn was at one time quoted as the world’s most often played musical by amateurs.

Crossing the Atlantic

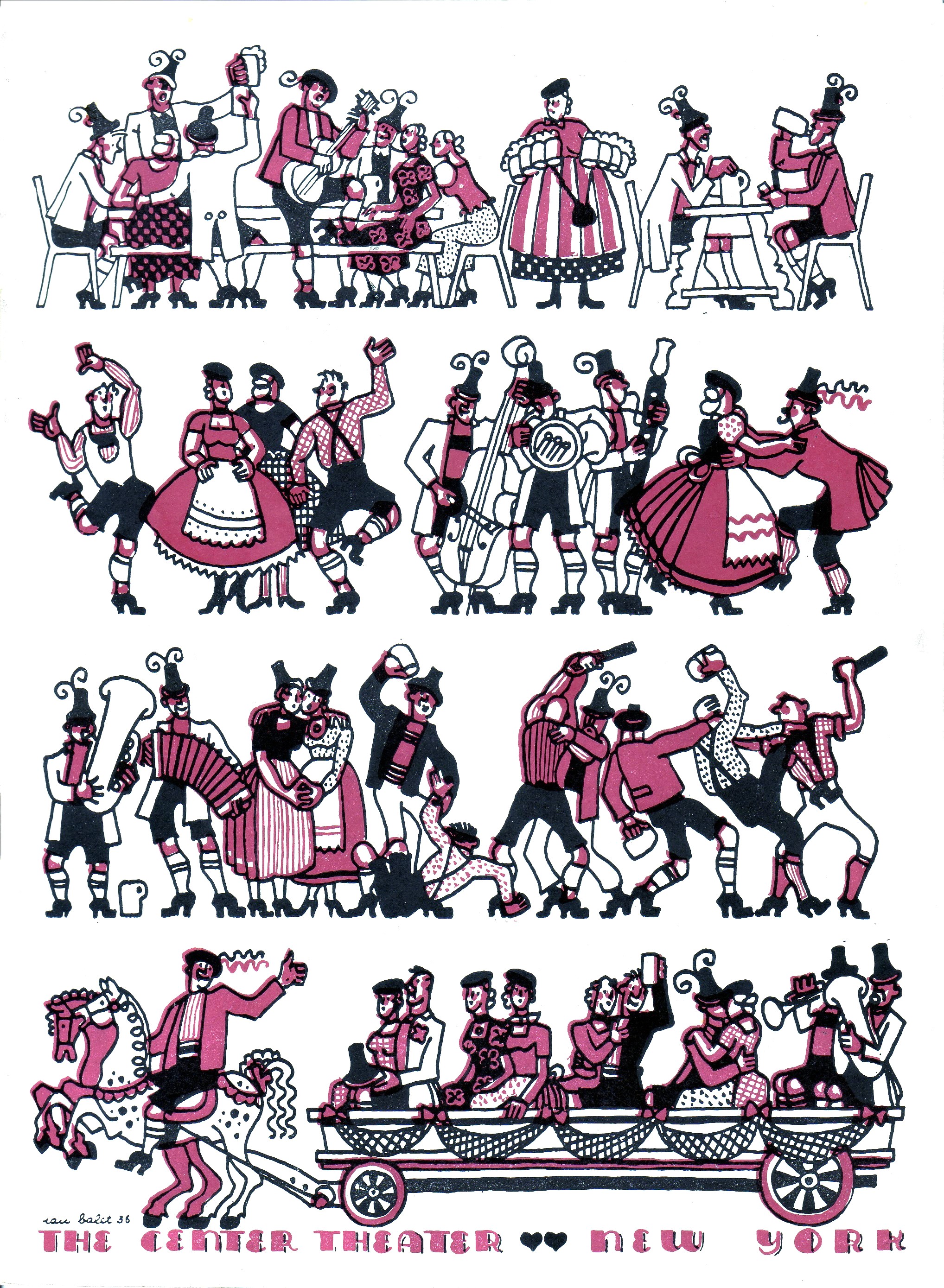

Program book for the 1936 New York production.

Despite its British success, White Horse Innis today – surprisingly – scarcely known in the United States, and thereby hangs a tale of intrigue, initial success, betrayal, misfortune and outright neglect. Sometime in 1931, Jacob Wilk, executive for Warner Brothers Films, approached Erik Charell with regard to a possible American production of White Horse Inn. At the time Charell was unavailable, under contract first to Ufa to produce films (Der Kongress tanzt, also with Robert Gilbert lyrics, but music by Werner Richard Heymann), and then subsequently Fox Pictures, for whom he directed Caravan in Hollywood.[22] With its financial reorganization, Fox’s interest in Charell and White Horse Inn lapsed, since Caravan had flopped. The earliest public announcement of an American Rössl disclosed in April 1932 that Broadway entrepreneur Earl Carroll[23] was negotiating with Oswald Stoll to bring the entire British production intact to New York upon its London closing; he claimed that the entire company could set sail and open in one month’s time.[24] Several months later the New York Times announced that Rockefeller Center’s management determined that their new RKO Roxy Theatre would cease showing films, and White Horse Inn was expected to be its first presentation; the Messrs. Shubert, Broadway’s most aggressive producers of operetta, had considered the project, but negotiations then fell through.[25]

In the summer of 1933 Erik Charell, now a refugee from the Nazi regime because of his Jewish background and homosexuality, accompanied by his production staff, arrived in New York on the Ile de France to negotiate an American production[26].

Charell’s intended partner was the American producer Martin Beck, who was unable to secure the Radio City Music Hall for its stage premiere, after he determined the production would be too large for his own 1200-seat Martin Beck theatre[27]. Charell claimed to have the financial backing of an English syndicate, and attempted to book a larger unidentified Broadway house. Alas for Charell, the summer of 1933 marked the commercial and economic nadir of the Great Depression in the United States. Despite the commercial successes of Jerome Kern’s Music in the Air, Vincent Youmans/Richard Whiting’s Take a Chance and Cole Porter’s Gay Divorce on Broadway in 1932, the first nine months of 1933 witnessed the premiere of no successful new musical productions, a collapse in sources of theatrical capital, and a diminished theatre-going public, who preferred the cheaper cost of films. Undaunted, Charell in early September 1933 announced that a “well-known brewery” was offering the English syndicate $25,000 for the beer concession to the American production[28]. Days later, the English syndicate terminated its negotiations for the Hippodrome[29] and abandoned the White Horse Inn project altogether[30].

Two years later in October 1935, Erik Charell, already in exile from the German regime, returned to New York to negotiate an American premier with prospective American producers and the film studios (MGM, 20th Century-Fox and Warner Brothers)[31]. No longer was the Hippodrome under consideration as a potential venue as it currently housed Billy Rose’s colossal vanity production, Rodgers & Hart’s Jumbo. Once again, the Center Theatre in Rockefeller Center, which had turned legit with The Great Waltz[32] in October 1934, then lapsed back into films in September 1935, was chosen as the premier venue. In February 1936 the New York Times finally disclosed that a triumvirate of producers, Rowland Stebbins, Warner Brothers and the Rockefellers would present White Horse Inn in September 1936[33]. Warner Brothers provided $150,000, Stebbins $75,000, Charell and his pool of investors $30,000, Rockefeller Center interests $10,000 in house renovations[34]. Laurence Rivers, Inc., Stebbins’ production company, retained sole billing.

Conspicuously absent from these accounts is the name Sir Oswald Stoll. Despite the production’s success in Great Britain, Stoll’s production rights evidently included only the UK and Australia; any option to produce in the United States had presumably lapsed. Consequently, rather than Americanizing Harry Graham’s UK script, Charell would later be compelled to commission an all-new, all-American adaptation of the German text and lyrics. Here was a unique opportunity to shed Graham’s operetta conventions for a faster, modern White Horse Inn.

It had taken Charell and his attorneys many months to conclude these complex negotiations to secure the hefty $200,000 capitalization.

But from the outset, the producers quarreled. Stebbins had wisely quit Wall Street in 1929 to pursue a career in show business. By his own admission a neophyte, he presented Marc Connelly’s black biblical parable The Green Pastures in 1930. Its improbable success and 640-performance run may have persuaded him of his own invincibility; his next six shows had all lost money. His expertise may have been questionable, when with regard to producing White Horse Inn, he confessed: “I am the only person in my family who’s never seen it.”[35] Warner Brothers was interested in White Horse Inn primarily as a film property, and agreed to co-finance the stage production with the intent of filming the show in 1937. The Rockefeller family interests hoped to establish the Center Theatre permanently as New York City’s largest popular legitimate stage venue to rival the now obsolete Hippodrome; for their share, the Rockefellers were prepared only to extend the stage 16 feet, and to pay for other such renovations and Austrian tyrol enhancements to the theatre.

Arrival of the tourists on the massive NY stage.

Stebbins was expected to return from Florida on 1 April 1936 for pre-production; several props from the London production had been salvaged and were already stored at the Center Theatre.[36] New York World-Telegram columnist Willela Waldorf welcomed confirmation of the show’s New York opening, noting that Leo Singer had announced it for production in 1934 at the Casino, and that Otto Harbach, lyricist for Jerome Kern’s Roberta, was sought for Americanizing the text (the man who wrote the lyrics for “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”[37]). A legal notice appeared in the New York papers on 5 May 1936, announcing that Jack L. Warner on behalf of Warner Brothers had acquired the exclusive film rights to White Horse Inn from Felix Bloch Erben, (the 1935 Austrian film by Carl Lamac notwithstanding), and intended to co-produce the New York stage production.[38] Al Jolson – the actor know for his portrayal of The Jazz Singer – reportedly brought the project to the attention of Warner Brothers, and on 12 July 1936, he announced his intention of returning to the legitimate stage, presumably as Leopold[39]. David Freedman was ultimately contracted to prepare the new American libretto; at the time of his signing, Freedman was the “most prolific and best known of radio script writers”[40] especially for his work for Eddie Cantor. He had contributed revue sketches to two Shubert revues, The Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 and The Show Is On, vaudeville dialogue for Smith & Dale, as well as numerous newspaper articles and co-authorship of Eddie Cantor’s biography My Life Is in Your Hands. Lyricist Irving Caesar was world famous as the lyricist for No, No Nanette, whose songs (“Tea for Two” and “I Want to Be Happy”) became international standards. He also provided the lyrics for George Gershwin’s first break-out hit “Swanee” (1918) popularized by none other than Al Jolson, and wrote the American adaptation of Robert Katscher’s Die Wunder-Bar as a vehicle for Jolson in 1930.

Ernst Stern’s fantasy costumes for the girl dancers.

Erik Charell arrived in New York harbor on the Normandie on 25 May 1936[41] for casting and pre-production, accompanied by Hans Müller, Max Rivers and Ernst Stern – all three Jewish refugees from their own country. The show was announced to open 5 September 1936[42]. Early casting ideas for possible Leopolds included, beside Al Jolson, Maurice Chevalier, Eddie Cantor, Bob Hope and Jack Oakie[43], Warner Brothers hoped to persuade either Eddie Cantor or Al Jolson to star as Leopold on stage or on film. However, both Cantor and Jolson had been absent from the musical stage since 1930, preferring the luxury of musical films. Both stars demanded that musical vehicles be tailored to their talents, whereas White Horse Inn was decidedly an ensemble show, not exclusively a vehicle for the role of Leopold. Under exclusive contract to Sam Goldwyn, Cantor currently commanded a fee of $175,000 per film, plus 15% of the gross, which no Broadway producer could hope to match[44]. On 24 July 1936 it was announced that diminutive Broadway comic Jimmy Savo had been signed by Charell. As a courtesy to his future producers, Savo invited Charell, Stebbins and Jacob Wilk (of Warner Brothers) to see his performance in a summer stock revival of Moliere’s The Would-Be Gentlemen. After seeing this show, Wilk determined that Savo was not capable of playing their leading man[45], and in a bitter public spat (“Not with our money”), resolved to break the actor’s contract; he was fired 19 August 1936. Savo’s agent Sam Lyons charged the producers with breach of contract before Actor’s Equity[46], and Savo finally agreed to accept 55% of his agreed weekly salary until 1 June 1937, or else the show’s closing[47]. Meanwhile, William Gaxton was eventually hired to star opposite young Kitty Carlisle as Katarina, as Josefa had been re-named. Gaxton was Broadway’s preferred leading man, masculine, confident, dapper, elegant, droll, but never outwardly funny. His principal stage partner, Victor Moore, with whom he co-starred in George & Ira Gershwin’s Pulitzer prize winning musical satire, Of Thee I Sing, and its sequel, Let ‘em Eat Cake, in 1931 and 1933, had cemented his stage persona as the straight man to Moore’s joke-meister. Although Gaxton savored success without Moore in Rodgers & Hart’s A Connecticut Yankee and Cole Porter’s Anything Goes, his un-remarkable singing voice was never recorded, and he was decidedly less fun without Victor Moore. Gaxton, arriving one week late in rehearsals, described Charell’s unique modus operandi:

This is the only show I have ever been in where we began using props at the opening rehearsals. I like it. Charell even rehearses off-stage noises from the beginning. The first day I rehearsed with the company I certainly hadn’t expected to hear the steamboat whistle blow on its cue. Well, the pitch wasn’t right, so they stopped the scene until they found the right note. Then they went back and let the whistle try again. The chorus and most of the company had been working a week or so before I arrived and they were using their props—bird cages, beer steins, or whatever they might be. That is Charell’s method. It was Belasco’s too…. Look at those rows and rows of seats. Everybody must see and hear. Still, the sound amplification in the Center Theater ought to make the hearing easy.[48] Kitty Carlisle’s principal stage credit had been as Prince Orlowsky in Champagne, Sec, a streamlined adaptation of Die Fledermaus in 1933.

At this time she was better known for her incipient film career in Paramount’s Murder at the Vanities, She Loves Me Not and MGM’s just released Marx Brothers caper, A Night at the Opera. A classically-trained singer, Carlisle had an easy soprano voice, personal beauty and charm to spare, and a gracious humor about herself. It’s unlikely that anyone would have thought her as wicked or naughty as Camilla Spira or Lea Seidl though.

Billy House, best known as a vaudeville comedian, got a big career break when cast as William McGonigle, the American name for Wilhelm Giesecke. His previous Broadway appearances have included the Shuberts’ Luckee Girl and The Street Singer, Walter Buck, Assistant Stage Manager, in Murder at the Vanities, followed by a takeover of Bernard Granville’s role in All the King’s Horses.

Robert Halliday, cast as Robert Hutton (Americanized Valentine Sutton/Dr. Otto Siedler), boasted a constant stream of Broadway musical/operetta credits since his debut in 1921, including Pierre in Sigmund Romberg’s mega hit The Desert Song, Robert Mission in Romberg’s equally successful The New Moon and Schani (Strauss Jr.) in London’s Waltzes from Vienna. The actress Carol Stone, comedian Fred Stone’s daughter, was signed to play Natalie (otherwise Ottolie/Ottoline), Hutton’s object of affection[49]. Buster West, a comic dancer, was chosen for the role of Sylvester/Sigismund; previous Broadway appearances in Greenwhich Village Follies (1923), George White’s Scandals (1926) and the forgotten musical Ups-a-Daisy lead to vaudeville tours of every major European city, according to his program biography.

The Emperor Scene: Kitty Carlisle and William Gaxton.

Internal squabbling was not limited to Stebbins and Warner Brothers. White Horse Inn afforded the producers a unique opportunity for promotional tie-ins, now common practice in theatre and film some 70 years later, but seldom deployed in the New York theatre industry in 1936. Whereas performers often lent their name or image to print advertisements for fashion, food or luxury items, as a testimonial, the White Horse Inn producers were more ambitious. Given the show’s name, it was a natural fit when White Horse whiskey proposed that a white horse sketch without any specific product wording be placed on the front curtain, for a $50,000 fee. While Stebbins and Warners were eager to accept the offer to defray the production’s hefty capitalization, Rockefeller family interests nixed the deal rather than be criticized for promoting liquor. Another brewery proposal was rejected as well on the same grounds. For a fee of $7,000, Stebbins, Warner Brothers, the Rockefellers and Charell did agree to accept New York’s largest and indisputably premiere department store Macy’s plan to remodel the lobby as an Austrian tyrol village, whereby ticket-holders entering the lobby were greeted by vendors dressed in authentic costume, selling ski outfits, sweaters, scarves and souvenirs. The theatre ushers were likewise costumed, and costumed vendors carrying baskets of souvenirs mingled with the audience before and after the performance, and during the interval. Macy’s further agreed to promote White Horse Inn with store window displays and in newspaper print ads.[50]

Meanwhile, massive construction was underway to transform the façade and interior of the Center Theater on Sixth Avenue to resemble an Austrian alpine village. The stage was extended 16 feet into the auditorium, and pine forests grew up to the ceiling. Cloud effects were designed to extend from the stage overhead above the audience. The accumulated cost of all these alterations to the front of house were estimated at $30,000. On 18 September 1936, 1256 costumes were delivered for the cast of 162, of whom 104 were chorus, with 8 changes apiece[51]. White Horse Inn also employed three goats, one dachshund, one pony, six pigeons (four of which are used, two being spares[52]), a symphony orchestra of 65 and stagehands numbering 56. Greater headaches arose from the mechanical cows, whose heads and tails sway in unison as they moo, each manipulated from behind the set by a fleet of stagehands with ropes. Rehearsals however did not go smoothly. On 23 September 1936, Variety reported that all spending on the production had been halted once the outlays reached $300,000, with the excesses now covered by Stebbins:

Reported that the temperamental antics of the stager (Charell) have caused almost constant turmoil within the Center. Interference in almost every department by Charell has been evident, it is claimed, since the time he insisted upon having his way about every detail. Disputes with representatives of the backers are known to have been frequent.[53]

William Gaxton refused to rehearse until his contract was signed, at double the salary offered to Jimmy Savo, and with onerous riders, including Gaxton’s right of approval of all his dialogue and lyrics. The producers had exhausted the traditional five weeks of rehearsals at reduced salaries, and for the sixth and final week the entire company was on full salary; Equity denied the producers’ appeals on the grounds that Charell had already staged the show numerous times throughout Europe, and ought to be able to complete the task within the allotted five weeks.

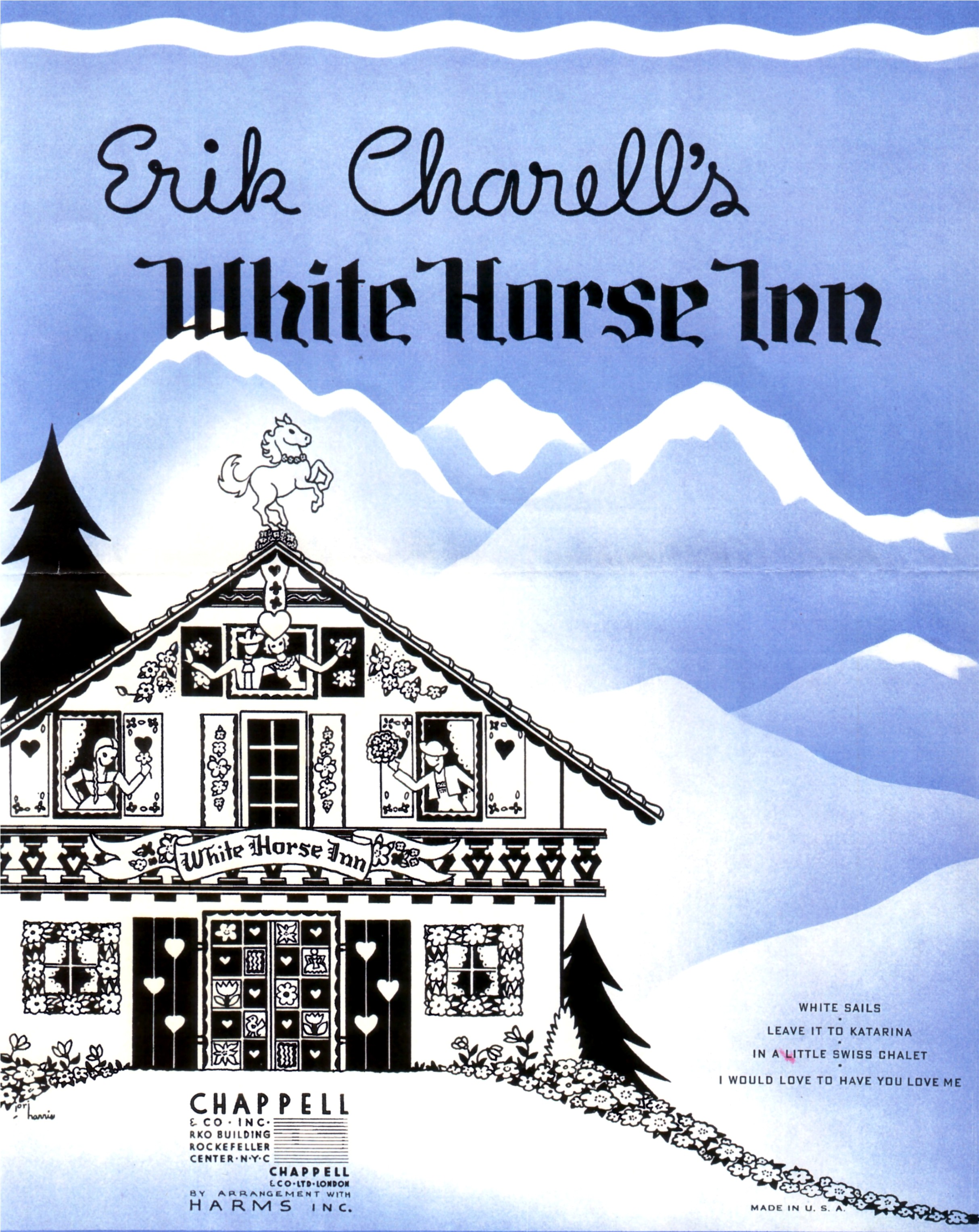

Sheet music cover from the New York production of “White Horse Inn”.

As in London, the basic narrative structure of the German original remained intact, but many more musical numbers were dropped or replaced with interpolations by other composers. Characters names and much of the topical humor were Americanized. Josepha became Katarina Vogelhuber. For New York audiences, Wilhelm Giesecke/John Ebenezer Grinkle, became William McGonigle, manufacturer of the one-piece Lady Godiva bathing suit, which buttons up the front with no back.[54] His rival’s son, Sigismund Sülzheimer/Smith, was reinvented as Sylvester S. Somerset, a Massachusetts manufacturer of the Goona Goona, with buttons in the back, none in front. McGonigle’s daughter Ottilie/Ottoline was renamed Natalie for American audiences. Otto Siedler, later Valentine Sutton in London, reappeared as Donald Hutton. Among lesser parts, Kathi, postmistress, became Hanni, to avoid confusion with the starring Katarina. Freedman’s script reveals it is markedly more contemporary and playful than Harry Graham’s language, decidedly more a musical comedy, as it is billed, than an operetta. The interpolations to the musical score and Irving Caesar’s lyrics are equally modern. The joyous refrain of “Im Salzkammergut” becomes very contemporary (telephones included) as “High Up on the Hills”:

High up on the hills – up on the hills,

Life begins, life and love are twins, you’ll agree;

You dance when you walk – sing when you talk –

You’re so gay, on a holiday, constantly;

There’s grape on the vine,

You can have your favorite wine,

Wines that cheer and steins that with beer overflow,

And when you’re alone, your telephone

Starts to ring, and a girl is yodelling,

Holdrio![55]

Erik Charell and his American producers took a free hand in adapting Berlin’s original Benatzky/Stolz/Gilbert/Granichstaedten score; strangely, any successful interpolations used in the previous English, Viennese, Hungarian, French or Australian productions were discarded[56]. The entire White Horse Inn score was freshly orchestrated by Hans Spialek, whose graceful and witty instrumentation blessed 12 Rodgers & Hart musicals, and nine Cole Porter shows. Nearly 50 years later, Spialek’s orchestrations for the 1936 Rodgers & Hart musical On Your Toes were restored for its 1983 revival, creating a sensation, and launching a vogue for recovering and recording historic musical theatre scores with their original orchestrations intact.

The White Horse Inn producers demanded the obligatory introductory song for their heroine, and thus Katarina and ensemble were given a new Jára Benes song “Leave It to Katarina” which many critics admired. Benes was a Czech composer of popular songs and films, based in Vienna; his operette, Auf der grünen Wiese premiered at the Vienna Volksoper in 1936, and was later filmed. The song’s charming music suggests it may have been the only new interpolation compatible with appeal of the original score. “It Would Be Wonderful” was revised into the heavy-handed “I Cannot Live Without Your Love.” London’s saccharine “Happy Cows” was discarded in favor of a choral “Cowshed Rhapsody” by the show’s German music advisor, Adam Gelbtrunk. The Stolz hit song “Your Eyes” acquired a parallel Irving Caesar lyric, “Blue Eyes” of comparable charm. Stolz’ other two duets (“You Too” and “My Song of Love”) for Hutton and Natalie were discarded as well; English composer Vivian Ellis contributed its Act 2 replacement “White Sails,” and a Richard Fall interpolation “The Waltz of Love” appeared in the Act 3 spot. William Gaxton as Leopold was denied the London hit “Good-Bye”[57] and offered instead an Eric Coates adaptation with the same name, “Good-Bye, Au Revoir, Auf Wiedersehn.” Sigismund’s self-titled comic turn, became a bland duet for Sylvester with Gretel, “I Would Like to Have You Love Me” by Tin Pan Alley[58] writers Gerald Marks and Sammy Lerner. Its generic music and lyrics are totally unrelated to the characters and plot, and would comfortably fit into any dozen musical comedies.

Katarina’s advice from the Emperor “We Prize Most the Things We Miss” won plaudits from some critics, but was not deemed worthy for publication.

A late Act 3 comic ballad for Sylvester and Gretel, penned by revue writers Will Irwin and Norman Zeno, “In a Little Swiss Chalet,[59]” was considered superfluous on opening night and then dropped. While Im weißen Rössl in its multiple international productions always freely accommodated musical interpolations, Charell and the American producers foolishly or inadvertently sabotaged one of the show’s greatest strengths, its hit score. Only three recognizable hit tunes (“The White Horse Inn,” “Blue Eyes,” and “I Cannot Live Without Your Love”) were retained, but with new and unfamiliar lyrics! None of the new songs achieved any popularity whatsoever. The only plausible rationale is that Warner Brothers, as was the then-common practice with musical films among all Hollywood studios, often junked a show’s original stage score for other new and inferior songs they owned or controlled.

Seen through the Critics’ Eyes: New York Reviews

The march of the waiters, as seen by Ernst Stern.

With the possible exception of Billy Rose’s Jumbo which capsized the preceding season at the Hippodrome, White Horse Inn was unquestionably the most lavish and eagerly awaited musical theatre premier of the New York season. Advance word of the show’s success in Berlin, London, Vienna, Paris, etc. created unreasonable expectations. Indeed, New York’s theatre critics often take offense when told any production has been a success elsewhere, provoking snide cultural slurs or derisive observations about superior local tastes. Happily, White Horse Inn elicited a handful of rave notices from the most influential critics. Brooks Atkinson wrote in the New York Times: “A hospitable evening seasoned by good taste in lavish showmanship.”[60] Richard Watts stated in the Herald-Tribune: “A beautiful colorful and sufficiently lively show…It is my private opinion that ‘White Horse Inn’ is several times livelier than the previous European spectacle ‘The Great Waltz’, and at least as handsome.”[61] And Gilbert W. Gabriel wrote in the New York American: “Here, believe me, is a very magnum of delights. You’ll soon be toasting Miss Carlisle with it. You’ll drink it with great gulps of pleasure in the costuming, the staging, the whole holiday air of the whole idea. You’ll have—in your good old way—a grand old time. So…Prosit. ‘White Horse Inn’!”[62] White Horse Inn was thus advertised in the daily papers: “Music, maids and minstrels by the million. The biggest thing in town for the money.”[63]

Rocky Mountains: Trouble in the Alpine Paradise

The public response for the first three months was exceptionally strong. After the opening, Charell trimmed thirty minutes running time, by shortening some of the dance sequences and cutting the duets “White Sails” and “In a Little Swiss Chalet,” so that the performance could conclude in less than three hours. The show’s advance sale and weekly grosses frequently outpaced its predecessor The Great Waltz with which it was so often compared. With a top ticket price of $3.85, the production grossed between weekly $40,000-$53,000 out of a possible $60,000 for the first 15 weeks of its run, against a breakeven of $30,000. White Horse Inn accumulated a profit of $160,000 against production costs of $263,000[64]. According to expected traditional seasonal patterns, attendance slumped after 1 January 1937, and White Horse Inn grossed between $31,000-35,000 for the next eight weeks. However, the producers were in open disagreement over promotion strategies, the future of the show, and the responsibility for covering weekly losses, should they occur. Both the New York Times[65] and Variety[66] reported that Warner Brothers wished to withdraw from the production, claiming its investment was intended merely to secure its rights to make the film version. A flurry of proposals and counter-proposals for Warner Brothers to withdraw, for Rockefeller to take over the production, and for salary cuts were made, and then rejected. Stebbins was vacationing in Florida at the time, and his general manager Charles Stewart, saw no reason to cut salaries when the production had posted no losing weeks[67]. Charell was not present for these meetings, because he was tending to the illness of his brother and manager, Ludwig Charell, on the West Coast[68]. Finally, Charell returned from the West Coast for one last look at White Horse Inn before returning to Paris. He announced that the production would tour next season.[69] Impresario Sol Hurok claimed in the New York press he would be interested in presenting a tour in the fall of 1937.[70] Milwaukee and St. Louis reportedly offered $300,000 in guarantees for touring dates the next season.[71] In hindsight, the failure of the production management to agree upon spending cuts and royalty reductions in advance during loss weeks, a common practice in commercial theatre, and to resolve their differences, doomed the show.

The dirndls for the chorus, designed by Ernst Stern.

Whereas originally White Horse Inn was expected to last until the end of May when business traditionally dips for the summer, rumors suggested the production might close by Easter. Belatedly, Variety announced that the weekly breakeven had been cut by $5,000 to $25,000; rent and royalties had been reduced, the cast was reduced by 19, the orchestra by 6.[72]On 14 March 1937, a forthcoming national tour of White Horse Inn was announced, beginning with an open end run in Chicago, and a series of one-week stands in major Eastern cities. Warner Brothers was reportedly cold to the idea of a national tour which might compete with their film.[73] Unless control of White Horse Inn were ceded to Rowland Stebbins, the production might close for good. In the face of rumors and confusion, morale backstage was not great. Gaxton announced that he would not be willing to tour in White Horse Inn, by some accounts jealous of the generous praise lavished upon his young co-star, Kitty Carlisle. White Horse Inn’s London librettist, Harry Graham, had died 30 October 1936 at age 61, while most unexpectedly, David Freedman, its American librettist, died in his sleep of heart disease 8 December 1936 at the young age of 39. At the time, Freedman was testifying against Eddie Cantor in a breach of contract lawsuit; at issue was Cantor’s verbal assignment of a disputed share in Cantor’s earnings to Freedman, his leading comedy writer for radio. Whether this legal action might have influenced Cantor not to appear in White Horse Inn is unknown. Cantor would undoubtedly have made an outstanding Leopold, even if he required the role be augmented to sole star status.

Undocumented and ignored by the recording and film industries

No American popular recordings whatsoever of any songs in White Horse Inn’s score were made during the New York run, inexplicable for the time. While Original Cast recordings were commonly made from a show’s hit songs in Berlin, London and Paris at the time, the practice in New York was not as widespread until the Oklahoma! 78rpm cast album won a huge public in 1943. Far more common were popular vocal 78rpms by big bands and popular vocalists. For example, contemporary rivals to White Horse Inn which played during its New York run were Cole Porter’s failure Red, Hot and Blue and Rodgers and Hart’s hit On Your Toes. The latter’s hit songs were recorded by Paul Whiteman, Ruby Newman, Hal Kemp and Henry King on the Victor, Decca, Brunswick and Bluebird labels. Red, Hot and Blue’s popular hits were recorded by Eddy Duchin, Ruby Newman, Will Osborne, Leo Reisman, Guy Lombardo and Leonard Joy on the same labels. The only plausible reason for this neglect is that White Horse Inn’s score was divided between eleven composers and lyricists, and two competing publishers, Chappell and Harms; however, to dispel this theory, the concurrent 1936 edition of the Ziegfeld Follies was divided between two publishers, and five of its songs were widely recorded. As was then the custom, William Gaxton, Kitty Carlisle and Carol Stone made a guest radio appearance with concert orchestra Sunday afternoon 25 October 1936 on the Magic Key program on WJZ radio station in New York singing songs from the show, but no known aircheck recordings are known to have survived.

In late March White Horse Inn advertised “last weeks” with the intent to close 3 April 1937, but many in the cast were incensed at the scheduled closing.

According to the New York Times, the production had posted a profit in 25 out of 28 weeks of its run, and the cast applied to Actors Equity to continue on a cooperative basis, which Equity refused.[74]A meeting of the Charivers Corporation, the corporate name for the producers, on Friday, 2 April 1937, won the production a brief reprieve and the production was announced to continue “indefinitely.” However, all the managerial indecision, indifference and squabbling had allowed the advance sale to dwindle to $11,000, and White Horse Inn closed on Saturday, 10 April 1937, after 221 performances. A season’s run such as White Horse Inn’s was respectable; to the public eye, it looked like a big hit. With Charell absent and no firm plans to tour, the production sets ($53,000) were burned, its costumes ($65,000) dispersed for $1500, its orchestrations lost. Charell returned to New York “in tears,” disgusted to find his hopes for a national tour destroyed[75]. Without a national tour, a complete set of orchestrations, any deal for stock or amateur productions, a film version or any American recordings of the production, White Horse Inn was swiftly forgotten. The St. Louis Municipal Opera, known nationwide for its popular summer season of open air musical revivals, staged its own White Horse Inn in the summer of 1938[76].

Going West: The White Horse Inn and Hollywood

Warner Brothers never did make any film of White Horse Inn; perhaps international political tensions made the jolly denizens of St. Wolfgang a dubious prospect for film success. Undaunted, Erik Charell, now unable to work in Austria after its German annexation, adapted, produced and directed a popular all-black jazz adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Center Theatre in November 1939. Swingin’ the Dream, this lavish and now legendary production featured Benny Goodman and his orchestra, Maxine Sullivan, Louis Armstrong, Bill Bailey, Jack “Moms” Mabley, the Deep River Boys, the Dandridge Sisters, dances by Agnes deMille, scenery inspired by Walt Disney’s cartoons, and a score by James Van Heusen. It collapsed after 13 performances, as did Charell’s hopes for an American career, and the future of the Center Theatre, thereafter consigned to a decade of ice shows and eventual demolition. On 19 October 1948, Charell announced plans to revive L’Auberge du Cheval Blanc at the Théâtre Chatelet in Paris on 10 November; he had commenced discussion with Warner Brothers about a possible film version. Meanwhile Max Hansen was starring as Leopold in the Swedish production Sommer i Tyrol. On 14 May 1952, industry reports announced that Charell at long last had secured the rights to Im weißen Rössl from Warner Brothers, with the intent of making a new on-site film shot in English, French and German. Neither the Austrian film of 1934, nor the German remakes of 1952 and 1960 were ever commercially released in the US, only the Argentine film El caballo blanco was shown briefly in 1948.

Arriving in the 21st Century

It was not until the summer of 2005 when the Ohio Light Opera presented a new English translation of White Horse Inn by noted American operetta authority Richard Traubner, that American audiences were able to see and hear White Horse Inn once again. This new version adhered more closely to the original Berlin score, shedding the later interpolations by Richard Fall, Jára Benes, Gerald Marks, Vivian Ellis and Eric Coates. The narrative was compressed from three into two acts, and the first act finale became “Salzkammergut.” Sigismund recovered his glorious ode to the self, which now sounds like this:

Why is it Sigismund’s a really gorgeous spec’men?

Why is it Sigismund’s a very dashing prince?

Why is it men, on seeing him, feel so much less men?

Why is it he’s the one—and none before or since?

Why is it Sigismund is so divinely handsome?

Why is it Sigismund shines out in any room?

Why is it mothers, far and wide, would pay a ransom

To get a Sigismund, a Sigismund, as groom?[77]

The Berlin cast of “Im weißen Rössl”, 1930.

Once again, Giesecke becomes a vacationing Berliner (not an Englishman or American on holiday), and the only interpolations were those by Benatzky and Stolz (“Im Prater blüh’n wieder die Bäume”). Perhaps now American audiences will be free discover the joys and humors of Im weißen Rössl in a translation closer to the original intended by Hans Müller, Ralph Benatzky, Robert Gilbert and Erik Charell?

Given the success of the “Encores Series” in New York, and “Reprise!” in Los Angeles, whose concert stagings of classic musicals in concert form with full original orchestrations (and subsequent CD releases) have enabled new generations to rediscover great musical theatre scores like the Romberg operetta The New Moon, Erik Charell’s Broadway White Horse Inn is now ready to recapture its English-speaking audience in all its former glory.

[1] V. Wittner, „Charells ‚Weißes Rößl’“, in: BZ am Mittag, 10. November 1930.

[2]PEM(Paul Markus), Und der Himmel hängt voller Geigen, Berlin: Blanvalet 1955, S. 139-140.

[3]V. Wittner, a.a.O.

[4]The present-day home to the English National Opera (ENO).

[5]“Variety” or “music hall” were the terms commonly used in England for a loosely assembled entertainment of performers, novelty acts, sketches, specialties and musical numbers, changed weekly. This was known as “vaudeville” in France and the United States.

[6]Felix Barker, “The House that Stoll Built: The History of the Coliseum Theatre,” Frederick Muller Ltd., London, 1957, pp. 205-217.

[7]V. Wittner, a.a.O.

[8]From the British Midlands, which suggests “provincial” to London audiences.

[9] (o.A.), “White Horse Inn”, in: The Sunday Times, 4. Dezember 1931.

[10] H.H., “White Horse Inn”, in: The Observer, 17. April 1931.

[11]Judy Blair in Little Tommy Tucker, Dolly in Rio Rita (both 1930), Babs Bascombe in Follow Thru (1929) later succeeding Ada May as its star, Peggy Ann (starring role on tour), Happy-Go-Lucky, No, No Nanette, Mercenary Mary, Yoicks etc.

[12]Harry Graham, White Horse Inn, production typescript, circa 1931, on deposit at New York City Public Library, Lincoln Center.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Barker, pp. 205-217.

[15](o. A.), “White Horse Inn reaching $40,000 gross weekly at Coliseum, London,” in: Variety, 13 May 1931.

[16]C. Hooper Trask, “But the Germans Like It,” in: New York Times, 4 November 1928; “More Musical Musketeers,” in: New York Times, 13 October 1929; “Mainly Erik Charell: Turning to a Native Form of German Music, He Achieves Success,” in: New York Times, 28 December 1930.

[17](o. A.), “Operetta in London Has a Cast of 250,” in: New York Times, 27 April 1931.

[18] G.W.B., “White Horse Inn”, in: The Era, 15. April 1931.

[19] H.H., “White Horse Inn”, in: The Observer, a.a.O.

[20]One of several theatrical licensing agencies which administer performance rights and royalties for professional stock, regional and amateur productions.

[21]Maschwitz and Grün formed a loose partnership in writing English language pasticcio operettas drawn from light classical composers: the Hungarian confection Paprika (also known as Magyar Melody) in 1938 and 1939, Waltz Without End (1942, after Chopin), Summer Song (1956, after Dvorák).

[22](o. A.), “That ‘White Horse Inn,’” in: the New York Times, 16 August 1936.

[23]Earl Carroll was a rival to Broadway producers Florenz Ziegfeld and George White in producing his own series of annual revues 1923-1940. Carroll’s were notable more for the naked female form than for their wit, spectacle or memorable songs. Carroll produced editions of his Earl Carroll’s Vanities in 1930, 1931 and 1932, a comparable Earl Carroll’s Sketchbook in 1929 and 1935, and combined his spectacular revue components into a murder mystery musical, Murder at the Vanities in 1933.

[24](o. A.), “May Get White Horse Inn: Earl Carroll hopes to bring successful play here,” in: the New York Times, 23 April 1932. Carroll’s claim from his own press office resonates today as more of an entrepreneurial boast than a serious proposal. He’d been compelled to lease his own theatre, the Casino, to his arch-rival Florenz Ziegfeld, for a revival of Show Boat. The sheer logistics of mounting a White Horse Inn production required several months of prior planning. It’s also unlikely that Actors Equity would have permitted a visiting all-English company at a time of severe local unemployment.

[25]Howard Barnes, “The Playbill: Lunts in Shakespeare,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 15 January 1933.

[26](o. A.), “White Horse Inn is projected here: Spectacular play, with cast of 250, would turn theatre into village—London backing,” in: New York Times, 22 July 1933.

[27]Herbert Drake, “Producers and Plays,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 30 July 1933.

[28](o. A.), “Gossip of the Rialto,” in: New York Times, 10 September 1933.

[29]The Hippodrome was a vast, 5200-seat theatre which occupied half a city block on Sixth Avenue between 43rd and 44th Streets in New York City. Built in 1905 to house mammoth spectacles, it had seldom operated profitably under a succession of theatrical managements. It was demolished in 1939.

[30]George Ross, “So This Is Broadway: Brewery Mourns as “The White Horse Inn” loses its $100,000 Angel,” in: New York World-Telegram, 18 September 1933. (o. A.), “Production abandoned: White Horse Inn will not be seen here this season,” in: New York Times, 20 September 1933.

[31](o. A.), “News of the Stage,” in: New York Times, 12 October 1935.

[32]American adaptation by Moss Hart of London’s Waltzes From Vienna, produced by Oswald Stoll at the Alhambra Theatre 17 August 1931 for 607 performances. The English production was itself an adaptation of the Viennese singspiel Walzer aus Wien (1930).

[33](o. A.), “News of the Stage,” in: New York Times, 20 February 1936.

[34](o. A.), “[White Horse] Inn, with a cast of 130, will be second $250,000 show in Center,” in: Variety, 5 August 1936.

[35]Donita Ferguson, “White Horse Inn, the Showpiece of 1936-37,” in: New York Woman, 23 September 1936.

[36]Howard Barnes, “The Playbill: Big Names for Golden: [White Horse] Inn again,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 2 February 1936.

[37](o. A.), “Stebbins to produce The White Horse Inn;” George Ross, “So This Is Broadway,” in: New York World-Telegram, 14 April 1936.

[38]Cost of film rights, $150,000. Contract with Felix Bloch Erben dated 3 April 1936.

[39]Jolson would make an implausible Leopold. He was accustomed to having stage, and now film, vehicles tailored to show off his exclusive talents. White Horse Inn’s score was not in his style, and would have required more than just a few interpolations to fit his demands.

[40]David Freedman obituary, in: Variety, 9 December 1936.

[41](o. A.), “News of the Stage,” in: the New York Times, 25 May 1936.

[42]Louis Sobol, “The Voice of Broadway,” in: New York Evening Journal, 25 May 1936.

[43]George Ross, “So This Is Broadway,” in: New York World-Telegram, 14 July 1936.

[44]Richard Barrios, “A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film” (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 347.

[45](o. A.), “Big Specs’ Coin Troubles: Turmoil at Center when Warners try to withdraw—Rockefellers’ Idea of Salary Cuts stymied,” in: Variety, 20 January 1937.

[46]Actors Equity is the union of professional stage actors, a closed shop.

[47](o. A.), “Big Spec’s Coin Troubles,” in: Variety, 20 January 1937, states that Savo received $550/week for the run. Thus his salary would have been $1000/week. (o. A.), “News of the Stage—Savo controversy settled,” in: New York Times, 31 August 1936.

[48]Helen Ormsbee, “Gaxton Finds Great Difficulty in Filling Center Theater Stage,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 27 September 1936.

[49]Her prior credits were minor, non-musical: Spring in Autumn (1933), Mackerel Skies, Jayhawker, and one film, Freckles.

[50]Ibee,in: Variety,, 7 October 1936.

[51]Howard Drake, “News of the Theatres,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 18 September 1936.

[52]Bosley Crowther,“Kitchen of White Horse I,” in: New York Times, 22 November 1936.

[53](o. A.), “Halt Called on Spending in “Inn” as Full Pay Starts with Show Not Ready; Erik Charell’s Antics,” in: Variety, 23 September 1936.

[54]Already in the 1934 Austrian film, the men’s underpants had been exchanged for a bathing suit. More sexy, perhaps, but not as incongruously funny.

[55]Irving Caesar and David Freedman, White Horse Inn typescript, 1936, on deposit at New York City Public Library, Lincoln Center.

[56]Dropped were Stolz’ “Adieu, mein kleiner Gadeoffizier” from Das Lied Ist Aus film which became “Good-bye” in London; Australia’s “Lend Me a Dream” by Ivor Novello; France’s “Je vous emmènerai dans mon joli bateau” composed by Anton Profès; Vienna’s two by Granichstaedten “Ich hab’ es fünfzigmal geschworen” and “Zuschau’n kann I net.”

[57]Perhaps because Harry Graham’s lyric “I go to fight a savage foe” and Leopold’s last stand for the Fatherland sounded particularly militaristic and lacked Leopold’s self-deprecatory humor.

[58]Popular song writers, not known for their theatrical expertise or reputation.

[59]Swiss (?) you may rightly ask. Perhaps no one told Messrs. Irwin and Zeno that the show White Horse Inn and its historical basis “Im Weissen Rössl” are set in Austria on the Wolfgangsee, not Switzerland!

[60]Brooks Atkinson, “White Horse Inn an Elaborate Musical Show, Opens the Season in Rockefeller City, in: New York Times, 2 October 1936.

[61]Richard Watts, Jr., “The Theatres: Lavishness in the Tyrol,” in: New York Herald-Tribune, 2 October 1936.

[62]Gilbert W. Gabriel, “White Horse Inn, That Celebrated Spectacle in Mr. Rockefeller’s Center,” in: New York American, 2 October 1936.

[63]Stage Magazine, December 1936.

[64](o. A.), “Big Specs’ Coin Troubles,” in: Variety, 20 January 1937.

[65](o. A.), “News of the Stage,” in: New York Times, 19 January 1937.

[66](o. A.), “Big Specs’ Coin Troubles,” in: Variety, 20 January 1937.

[67]Ibid.

[68]Ibid.

[69](o. A.), “Lunts Want Stravinsky to do a score; Kaufman Trial,” in: New York Daily News, 24 January 1937.

[70](o. A.), Newspaper clipping dated 4 February 1937.

[71](o. A.), Newspaper clipping dated 6 February 1937.

[72](o. A.), “White Horse Inn nut dropped to $25,000,” in: Variety, 24 February 1937; (o. A.), “[The Eternal] Road may fold before May 15, needing coin to tour, if and when,” in: Variety, 14 April 1937.

[73](o. A.), “Stallings-Schwartz show next for Center Theatre?” in: New York Daily News, 14 March 1937.

[74](o. A.), “News of the Stage: The White Horse Inn Dilemma,” in: New York Times, 2 April 1937. (o. A.), “News of the Stage: White Horse Inn to continue,” in: New York Times, 3 April 1937.

[75](o. A.), “Charell wants [White Horse] Inn to tour next season,” in: Variety, 21 April 1937.

[76]Close examination of the production typescript, on deposit at the New York Public Library, credited to David Freedman and Irving Caesar, reveals it is very closely modeled upon the New York version.

[77]New lyrics by Richard Traubner, copyright 2005, by permission of the author.

I published the French album of “L’Auberge du Cheval blanc” online http://comedie-musicale.jgana.fr/content/prog/prog022.pdf

full of photographs of the 1932 production.

and a lot of other documents here : http://194.254.96.55/cm/?for=fic&cleoeuvre=22