N.N.

The Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter No. 106

December 2023

In the summer of 1876 Jacques Offenbach visited Philadelphia. At “The Offenbach Garden,” located on the southeast corner of Broad and Cherry Streets in the center of town, Offenbach conducted the inaugural concert on Monday night, June 19, 1876 in the midst of city’s summer-long celebration of the Centennial of the Declaration of Independence. Among the 60 musicians in the orchestra was a 21-year-old violinist named John Philip Sousa. In the fall of 1876, the building became, as seen below, a “Horse and Carriage Bazaar.” It was torn down in 1893 and replaced by an eight-story Odd Fellows Temple, which lasted until it was removed in 2008 for the expansion of the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

“The Offenbach Garden”. (Drawing by the American artist, Frank Hamilton Taylor (1846-1927) courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia)

The following article from 27 June, 1876, provides interesting insights into America and the city whose blue laws prohibited Offenbach’s Grand Sacred Concert two days earlier on 25 June. The laws of course could not prohibit the sold-out performance of La Jolie Parfumeuse at the Arch Theater conducted by Offenbach. The December Issue of the Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter reprints this article that is well worth reading, because of the way “operetta” or rather opéra bouffe is characterized:

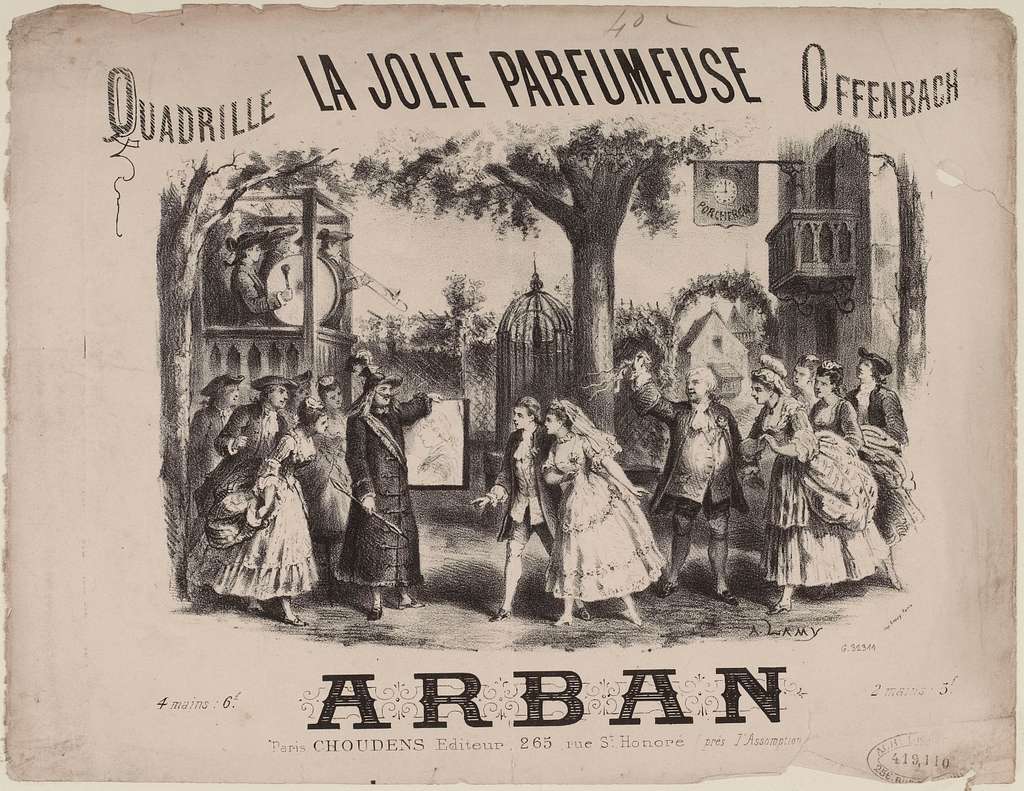

Sheet music cover for an Offenbach quadrille based in tunes from “La Jolie Parfumeuse”. (Photo: Choudens)

Opéra bouffe is a subject that a discreet critic would rather shun. If he have any regard for his conscience and for the public morals or the public taste, he cannot well commend it; to condemn it is not only to pronounce the public taste all wrong and the public morals no better than they should be, but to suggest an assumption of superior virtue, toward which, when exhibited in a daily newspaper, a scoffing public is somehow apt to take an attitude of skepticism.

Nevertheless, when M. Offenbach himself comes among us and treats us to an exhibition of La Jolie Parfumeuse, an opera in which he has reached the highest development or the lowest degradation – as you chose to put it – of his art, we must say something, and there is no apparent reason why it should not be said sincerely. In the first place, it is to be observed that opéra bouffe is not an isolated phenomenon. It is but one manifestation of a spirit that just now pervades the art of Continental Europe, and is shown in painting and sculpture and literature no less than in music and the drama. Take the work of the fashionable French painters, or more especially the pictures of the Spanish-Italian school which our rich amateurs import at such fabulous prices. It is nothing but opéra bouffe on canvas.

Amorous old men in fantastical attire leering at immodest girls; bedizened courtesans loitering in palace gardens, setting traps for wealth and station; court jesters making sport of dignitaries – whatever the subject, the picture has nothing in it but reckless laughter or a cynical sneer. The spirit of opéra bouffe is deeper than its indecency.

“Die neuesten Noten des Herrn Jacques Offenbach,” i.e. the latest compositions from Mr. Jacques Offenbach. From: Kikeriki, 1865.

La Grande Duchesse, for example, is not violently immodest, and yet it remains the type of work of its class, and it is quite as immoral as most of them. It is not so much that vice triumphs over virtue as that there is no such thing as virtue. Honor and earnestness, love and duty, purity, sincerity and the rest – all these are the silliest abstractions, and life but a prodigious joke. It is not difficult to understand how this sort of thing, expressed in words and music that all could understand, took the popular mind, say in France in the later years of the Empire, or how people who saw no way to cure the realities of life found them easiest endured by laughing at them.

Jacques Offenbach photographed by Nadar in the 1860s.

A generation ago all this would have been incomprehensible to Americans, to whom life had always been very real and earnest; but later years have made a change. We have seen so much of opera bouffe in our own affairs – the vogues in prosperity, the incapables in power, the flush and glitter and tinsel everywhere – that we too have learned to laugh at it. Of course the license that goes with this leads to licentiousness and La Jolie Parfumeuse is a natural development of the Duchesse of Gerolstein; and yet we will do the good people who crowded the Arch Street Theater last evening the justice to say that we do not believe that many of them understood the nastiness of the play.

They saw Aimee looking as fresh and mischievous as ever in her youth, singing and chattering as gaily as a girl; they saw the irrepressible Frenchman laughing and strutting upon the stage in the utmost good humor with himself and everybody; they saw a whole party, in short, apparently enjoying themselves to the utmost and singing the jolliest tunes, and though they did not understand a word of it they laughed at it all heartily, and cheered the composer who had created all this merriment. It is of very little use to tell these people that the play is indecent, the music trifling and the whole performance unworthy of an earnest, sober-minded community.

“Be virtuous and you will be – laughed at” is the motto of opera bouffe, and we are afraid that if a company of M. Offenbach’s Parisians could set the critic up on the stage and execute a dance around him, the sympathies of the audience would not be with the critic. With this much of preface it is only needful to say of the performance last night – which, by the way, was somewhat delayed by the non-arrival of the actors’ luggage – that it was as sparkling as Aimee’s performances always are, with something more added in the presence of M. Offenbach, who conducted the orchestra with much spirit, and was very cordially received by the large audience.

Much of the company are familiar to our theatre-goers, though some are new, but it is altogether a homogeneous company, that does what it attempts to do thoroughly well, with such apparent enjoyment and naivete as quite to disarm criticism.

To read a discussion with operetta historian Kurt Gänzl on the pornographic side of the genre in the 19th century, click here.