Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

The son of a German bookbinder, music-teacher and cantor called Eberst, but known as Offenbach, the young Jacob was given a good musical education from an early age. When he was 14 years old, his father took him to Paris where he secured a place at the Conservatoire (becoming Jacques instead of Jacob) but, after a year of studies, he left to earn a living as an orchestral cellist, ultimately in the orchestra of the Opéra-Comique. He progressed from orchestral playing to solo work and, in the 1840s, gave concert performances in several of the world’s musical capitals.

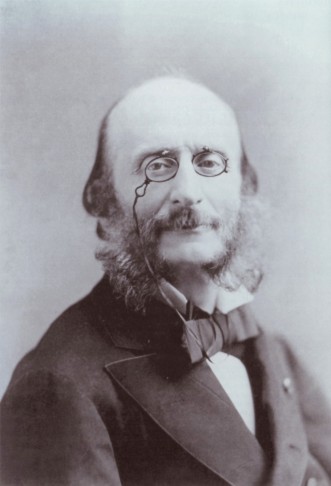

Jacques Offenbach in 1876, four years before his death.

Offenbach began writing music almost at the same time that he began performing it, at first producing occasional pieces, orchestral dances and instrumental and vocal music before, in 1839, he was given the opportunity to compose for the stage for the first time with a song for the one-act vaudeville Pascal et Chambord, produced at the Palais-Royal. That commission, however, had no tomorrow and, although Offenbach began writing with serious intent for the stage in the 1840s, he found that he was unable to get his works staged. The Opéra-Comique, the principal producer of lighter musical works, rejected his efforts and although Pépito, a pretty if slightly self-conscious little opérette housing some parody of Rossini, was played briefly at the Théâtre des Variétés, he was obliged to mount performances of his other short pieces under fringe theatre conditions to win a hearing. Not even when he was nominated conductor at the Théâtre Français in 1850, a post which led him to be called upon to supply such scenic and incidental music and/or songs as might be required for that theatre’s productions, did he succeed in getting one of his opérettes produced. Then in 1855, he launched himself on the Parisian stage from two different fronts.

On the one hand, with the help of a finely imagined and funny text by Jules Moinaux, he managed to place one of his opérettes at Hervé’s Folies-Nouvelles. This piece, Oyayïae, ou La Reine des îles, was in a different vein from his previous works, works which had been written rather in the style of a Massé or an Adam, with the polite portals of the Opéra-Comique in sight. Oyayaïe was written in the new burlesque style initiated and encouraged by Hervé, and it rippled with ridiculous and extravagantly idiotic fun. There was not a milkmaid or a Marquis in sight and the show was peopled instead by the folk of burlesque with Hervé himself at their head, in travesty, as the titular and cannibalistic Queen of the Islands.

By the time that Oyayaïe had found her way to the stage, however, Offenbach had already set another project on its way. The year 1855 was the year of the Paris Exhibition, and the city’s purveyors of entertainment were preparing for lucratively larger audiences than were usual as visitors from out of town and overseas poured into Paris. It seemed like a good time to be in the business. Thus, Offenbach, who had managed the production of his early unwanted works himself and who now saw Hervé presenting his own works successfully at the Folies-Nouvelles, decided to become a manager. He took up the lease of the little Théâtre Marigny in the Champs-Élysées, rechristened it the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, and opened with a programme made up of four short pieces by J Offenbach: a little introductory scena Entrez Mesdames, Messieurs, a virtual two-hander for two comics Les Deux Aveugles, the three-handed opéra-comique Une nuit blanche and a little pantomime Arlequin barbier. Les Deux Aveugles proved a major Parisian (and later international) hit, Une nuit blanche (which also subsequently became much favoured in English under the title Forty Winks) supported it happily, and Offenbach’s little theatre and its programme became one of the most successful entertainments of the Exhibition season. Thus launched, the composer/producer began to vary his programme, taking in some pieces by other writers, writing himself four further opérettes and two further pantomimes and scoring a second significant success with the sentimental scena (‘légende bretonne’) Le Violoneux in which the young Hortense Schneider made her first Paris appearances.

Once the end of the summer season arrived, however, accompanied by the closing of the Exhibition, it soon became clear that the little theatre way out in the Champs-Élysées was no longer a good proposition. Offenbach needed to shift his activities to a more central location if he were to continue as he had begun. He leased an auditorium in the Passage Choiseul, gained a permit in which the limit to the number of characters allowed in his pieces was raised from three to four, and opened, still as the ‘Bouffes-Parisiens’, at the end of December with a programme which featured but one piece of his own. However, that one piece was a winner. Ba-ta-clan was a return to the burlesque genre of Oyayaïe, and it gave Offenbach the producer and Offenbach the musician a fresh success comparable to that of Les Deux Aveugles. The new house was rocketed off to the same kind of start as the old one had been. The successes of his winter season included Offenbach’s melodrama burlesque Tromb-al-ca-zar and an adaptation of Mozart’s little Der Schauspieldirektor as well as the prize-winning efforts of two neophyte composers, Georges Bizet and Charles Lecocq, before the happy manager moved back to the Champs-Élysées for the summer with a programme including such new pieces as La Rose de Saint-Flour — a piece in the rustic opérette vein of Massé’s Les Noces de Jeannette or of Offenbach’s own Le Violoneux — and Le 66.

At the end of this second summer, Offenbach abandoned his first little home, and established himself on a full-time basis at the Passage Choiseul, now the one-and-only Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. There he continued to mount an ever-changing programme of short pieces, through the year 1857 (Croquefer with a fifth character semi-mute, Une demoiselle en loterie, Le Mariage aux lanternes etc.) and into 1858 (Mesdames de la Halle, with a full-sized cast at last permitted, and a musical version of Scribe and Mélesville’s little vaudeville La Chatte metamorphosée en femme), whilst taking the company and its repertoire on tour to Britain and to Lyon, to command performances, and managing to lose money all the while.

The restrictions as to the size of his productions having finally been withdrawn, Offenbach now stretched out for the first time into a more substantial work. October 1858 saw the Bouffes-Parisiens’ first production of a full-sized, two-act opéra-bouffe, a piece written in an extension of the Hervé-style which Offenbach and his librettists had carried so successfully through from Ba-ta-clan to Tromb-al-ca-zar and Croquefer. This style blossomed into something on a different scale in Orphée aux enfers, a gloriously imaginative parody of classic mythology and of modern events decorated with Offenbach’s most laughing bouffe music. The triumph of Orphée aux enfers put the Bouffes-Parisiens on a steady footing, and those corners of the international theatrical world which had not yet taken more notice of Offenbach than to pilfer such of his tunes as they fancied for their pasticcio entertainments began to wake up to the significance of the new hero of the Paris musical theatre and his work.

However, in spite of its great home success (228 successive performances at the Bouffes) and the wide spread of the popularity of its music, Orphée did not, at the time, produce the major change of emphasis in the international musical theatre that, in retrospect, might have been expected. It took a number of years, further shows (and not always the same one for every area) for the Offenbach pen to do that.

In the meanwhile, there were further successes — financial, or at least artistic — to come. The year 1859 brought two more: the short Un mari à la porte and Offenbach’s second full-length piece, the hilarious burlesque of all things medieval Geneviève de Brabant which, although it was a financial loser, confirmed the triumph of Orphée at the Bouffes-Parisiens. But there were also some real and substantial failures. When Offenbach moved outside his usual genre and finally forced the gates not only of the Opéra-Comique (Barkouf, to a libretto co-written by Scribe) but also of the Opéra (the ballet Le Papillon), he had two thorough flops. Back at the Bouffes, however, he produced in 1861 a third triumphant full-length work, the Venetian burlesque Le Pont des soupirs, the shorter but no less successful La Chanson de Fortunio and the Duc de Morny’s delightful Monsieur Choufleuri restera chez lui le…, followed in 1862 by the sparkling musical comedy Le Voyage de MM Dunanan père et fils, the little M et Mme Denis and, at his preferred spa town of Ems, Bavard et Bavarde a little piece which he subsequently worked up into a larger one as Les Bavards. But, whilst the successes piled up, the money did not. The dizzily spending Offenbach was not a talented manager and the series of outstandingly popular shows which should have made his fortune instead left the Bouffes-Parisiens almost permanently in the red. After the production of M et Mme Denis he was obliged to give up the theatre he had begun, and in 1863 the only fresh Offenbach music premièred in Paris was a song written for a little Palais-Royal vaudeville, Le Brésilien, by his old collaborator, Ludovic Halévy, and the librettist’s newest partner, Henri Meilhac.

Ems, again, was the venue for one of his tiniest and sweetest pieces, Lischen et Fritzchen, and Vienna — where his works had begun to raise interest — the chosen city for his next venture into the area that had suited him so ill in 1860: Die Rheinnixen, an opéra-comique produced at the Vienna Hofoper, proved as total a failure as had Barkouf in Paris. Offenbach returned to the Parisian theatre with Les Géorgiennes, less successful perhaps than his previous three-act shows but still back in his ‘own’ world, and then, at what was clearly a crucial point in his career, he began the collaboration which would lead him to an even more outstanding position in the musical theatre than that he had already conquered with Orphée, Geneviève and Le Pont des soupirs.

Halévy and Meilhac joined the composer to write his second burlesque of classic antiquity, La Belle Hélène. Produced by Cogniard at the Théâtre des Variétés in December 1864, the piece won its trio of authors a ringing success such as Paris had not seen in years. And now Offenbach began his real take-over of the world’s stages: Vienna was conquered in 1865 with Geistinger’s Die schöne Helena, and as Offenbach, Halévy and Meilhac swept the stage of the Variétés with further burlesque triumphs in Barbe-bleue (1866), La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867), Les Brigands (1869) and the rather less burlesque but ultimately equally successful La Périchole (1868), London fell belatedly before Emily Soldene in Geneviève de Brabant and Julia Mathews’s La Grande-Duchesse, whilst in America Lucille Tostée’s La Grande-Duchesse gave serious impetus to a craze for opéra-bouffe in general and for the works of Offenbach in particular. And at home, the composer continued to turn out successes: the glittering comedy-cum-opérette La Vie parisienne for the Palais-Royal, the frivolous La Princesse de Trébizonde premièred at Baden-Baden before taking over the stage of the Bouffes-Parisiens, and the little bouffonnerie L’Île de Tulipatan. Les Bergers, a sardonic three-part look at fidelity in love through the ages, and La Diva, a vehicle for Schneider, both staged at the Bouffes, and two further pieces for the Opéra-Comique, Robinson Crusoe and Vert-Vert, proved less popular.

Les Brigands was playing at the Variétés when the Prussian army marched into Paris. Offenbach, like his chief competitors of times before and after, Hervé and Lecocq, marched quickly out and he spent the year of the conflict capitalizing on his now-thoroughly-spread fame around the world. When he returned, however, things did not take up where they had left off. The days of opéra-bouffe were done, and so were the days when Offenbach, Halévy, Meilhac and their star Hortense Schneider reigned over the Paris musical theatre and its glittering audiences. Hervé-esque burlesque with its weirdly extravagant tales and laughing music was no longer the order of the day, the dazzling gaiety of the Variétés shows was of yesterday. The fashion, like the régime, had changed. Offenbach still found hits: the grand opéra-bouffe féerie Le Roi Carotte owed both some of its success and also its truncated run to an extravagant production which made it impossible to balance the books, La Jolie Parfumeuse (1873) and Madame l’Archiduc (1874) both found genuine international successes one level below his greatest opéras-bouffes, and a Christmas show for London, Whittington, fared much better than a Vienna one, Der schwarze Korsar (23 performances). But none was a Grande-Duchesse or a Belle Hélène.

At the same period, however, Offenbach decided almost perversely to go back into management. He took the Théâtre de la Gaîté and there staged revivals of his two earliest Bouffes-Parisiens successes, Orphée aux enfers and Geneviève de Brabant, and of La Périchole, each of which he expanded to larger proportions, with mixed results: if the Orphée took least well to having additional songs and scenes stuck into its fabric, it did best at the box-office. However, box-office proved Offenbach’s downfall once again and a distastrously expensive flop with Sardou’s play La Haine found him once more an ex-theatre manager and financially in a parlous state.

He was also, now, for the first time for many years, not alone at the head of the French light-musical theatre. The emergence of Charles Lecocq and, above all, the younger man’s triumphs in 1872 with La Fille de Madame Angot and in 1874 with Giroflé-Girofla, had rather overshadowed Offenbach’s works of the same period, whilst the success of Robert Planquette’s Les Cloches de Corneville in 1877 was the kind of success which Offenbach had not known for nearly a decade. Against these works, the long run of the spectacular opéra-bouffe féerie Le Voyage dans la lune, the at-best semi-successes of La Boulangère a des écus and La Créole and the utter failures of La Boîte au lait and Maître Péronilla weighed sadly light.

However, Offenbach was by no means done. In 1878, the year of Lecocq’s latest triumph with Le Petit Duc, he found himself in tandem with one of the most efficacious and talented pairs of librettists of the day, Henri Chivot and Alfred Duru, and to their brilliant, action-packed text for Madame Favart he composed a score which more than did it justice. Madame Favart was no opéra-bouffe, and the music the 60-year-old Offenbach wrote for it had none of the brilliant fireworks of the scores of Orphée, Geneviève and Barbe-bleue. It was a period comic opera, a farcical tale of sexual hide-and-seek with a series of fine rôles and fine songs, and with both something of La Fille de Madame Angot and something of the Palais-Royal comedy about it. It was also a hit. The team repeated their success the following year with the splendid La Fille du tambour-major, the hit of the Parisian season, and thus Offenbach, who had known so many years at the top of his profession, was able to go out of it at the top. He died the following year of heart trouble, exacerbated by the gout and rheumatics which had dogged him all his adult life.

Following his death, his opérette Belle Lurette (completed by Delibes) was produced at the Théâtre de la Renaissance and overseas, and the opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann (completed by Guiraud) at the Opéra-Comique. This last piece finally gave him, posthumously, the success at the Opéra-Comique which he had always wanted so much, but which he had never been able to win during his lifetime.

Inevitably, after his death, and more particularly following the expiry of his legal copyrights, Offenbach’s shows and his music became carrion for the compilers of pasticcio shows in the same way that they had been in his earliest years. One of these, in the wake of the huge success of the Schubert biomusical Das Dreimäderlhaus, even attempted to set his music to a version of his life. Offenbach (arr Mihály Nádor/Jenö Faragó), produced at Budapest’s Király Színház (24 November 1920), fabricated a romance between the composer (song-and-dance comedy player Márton Rátkai) and Hortense Schneider (Juci Lábass) which seemed a little unnecessary, given the fact that he had allegedly had a long liaison with his other principal star, Zulma Bouffar, amongst others. It won a considerable success, racking up 150 performances in Budapest by 25 April 1921, being very soon revived (20 September 1922) and then exported in various versions to Vienna’s Neues Wiener Stadttheater (ad Robert Bodanzky, Bruno Hardt-Warden), with Otto Tressler as the composer and Olga Bartos Trau as Hortense, to Germany variously as Der Meister von Montmartre and Pariser Nächte and, under the title The Love Song, to America (13 January 1925), where Allan Prior impersonated the composer alongside Odette Myrtil as Hortense and Evelyn Herbert as his wife, Herminie.

The English-speaking theatre, which made merry pasticcio with the composer’s music in the 1860s and 1870s, to the extent of inventing a handful of Offenbach opérettes to texts the composer had never seen (including that of Lecocq’s Fleur de thé) has, in later years, largely preferred to play the unadventurously small group of his most favoured opérettes which have been kept in their repertoire rather than manufacture its own. Broadway was, however, treated to a piece called The Happiest Girl in the World (Martin Beck Theater 3 April 1961) which mixed bits of Offenbach with bits of Aristophanes and little success, and London to a piece called Can-Can (Adelphi Theatre 8 May 1946), another called Music at Midnight (His Majesty’s Theatre 10 November 1950) and a new opéra-bouffe, well in the spirit of the old ones, Christopher Columbus.

The French musical theatre, too, even at its nadir of recent decades, has still found the space to give revivals of many of Offenbach’s works rather than to paste-up ‘new’ ones. It is the German-speaking theatre which, by and large, has been responsible not only for the most drastic remakes of the original works but also for the largest number of pasticcio shows. From the very earliest days when Karl Treumann rewrote and had re-orchestrated Offenbach’s pieces to suit the personnel of his company and local tastes in comedy, Viennese managers concocted their own Offenbach shows but, after the turn-of-the-century years, even though there were plenty of Offenbach shows to play, the new ‘make-your-own-Offenbach-copyright’ shows began in earnest. Amongst them may be numbered Die Heimkehr des Odysseus (Carltheater 23 March 1917), a version of L’Île de Tulipatan with a pasticcio score as Die glückliche Insel (1 act, Volksoper 8 June 1918), a composite of music from Der schwarze Korsar and elsewhere and an E. T. A. Hoffmann tale made by Julius Stern and Alfred Zamara as Der Goldschmied von Toledo (Volksoper 20 October 1920), Fürstin Tanagra (Volksoper 1 February 1924), Der König ihres Herzens (Johann Strauss-Theater 23 December 1930), a remade version of Robinson Crusoe as Robinsonade (ad Georg Winckler, Neues Theater, Leipzig 21 September 1930), an Italian Straw Hat musical Hochzeit mit Hindernissen (Altes Theater, Leipzig 16 February 1930), Das blaue Hemd von Ithaka (Admiralspalast, Berlin 13 February 1931), Die lockere Odette (Edwin Burmester, Staatstheater, Oldenburg 25 February 1950), Die Nacht mit Nofretete (Romain Clairville, Theater am Rossmarkt, Frankfurt 13 November 1951), Hölle auf Erden (Georg Kreisler, Hans Haug, Nuremberg 21 January 1967), Die klassiche Witwe (1 act, Cologne 20 June 1969) and many others.

In Italy, as early as 1876, a certain Sgr. Scalvini brought out an extravaganza called L’Amore dei tre Melarancie at Rome’s Politeama with a score of pilfered Offenbach music.

1847 L’Alcôve (Pittaud de Forges, Adolphe de Leuven) 1 act Salle de la Tour d’Auvergne 24 April

1853 Le Trésor à Mathurin (Léon Battu) 1 act Salle Herz 7 May

1853 Pépito (Battu, Jules Moinaux) 1 act Théâtre des Variétés 28 October

1854 Luc et Lucette (de Forges, Eugène Roche) 1 act Salle Herz 2 May

1855 Le Decameron (Jules Méry) 1 act Salle Herz May

1855 Entrez Messieurs, Mesdames (Méry, Ludovic Halévy) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 July

1855 Les Deux Aveugles (Moinaux) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 July

1855 Une nuit blanche (Édouard Plouvier) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 July

1855 Le Rêve d’une nuit d’été (Étienne Tréfeu) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 30 July

1855 Oyayaie, ou la reine des îles (Moinaux) 1 act Folies-Nouvelles 4 August

1855 Le Violoneux (Eugène Mestépès, Émile Chevalet) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 31 August

1855 Madame Papillon (Halévy) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 October

1855 b (`De Lussan’ ie de Forges) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 29 October

1855 Ba-ta-clan (Halévy) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 29 December

1856 Un postillon en gage (Plouvier, Jules Adenis) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 9 February

1856 Tromb-al-ca-zar, ou Les Criminels dramatiques (Charles Dupeuty, Ernest Bourget) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 April

1856 La Rose de Saint-Flour (Michel Carré) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 12 June

1856 Les Dragées du baptême (Dupeuty, Bourget) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 18 June

1856 Le 66 (de Forges, Laurencin) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 31 July

1856 Le Financier et le savetier (Hector Crémieux, [Edmond About, uncredited]) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 23 September

1856 La Bonne d’enfant[s] (Eugène Bercioux) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 14 October

1857 Les Trois Baisers du Diable (Mestépès) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 15 January

1857 Croquefer, ou le dernier des Paladins (Adolphe Jaime, Tréfeu) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 12 February

1857 Dragonette (Mestépès, Jaime) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 30 April

1857 Vent du soir, ou l’horrible festin (Philippe Gille) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 16 May

1857 Une demoiselle en loterie (Jaime, Crémieux) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 27 July

1857 Le Mariage aux lanternes revised Le Trésor à Mathurin (Carré, Battu) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 10 October

1857 Les Deux Pêcheurs (Dupeuty, Bourget) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 13 November

1858 Mesdames de la Halle (Armand Lapointe) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 March

1858 La Chatte métamorphosée en femme (Eugène Scribe, Mélesville) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 19 April

1858 Orphée aux enfers (Crémieux, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 21 October

1859 Un mari à la porte (Alfred Delacour, Léon Morand) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 22 June

1859 Les Vivandières de la grande armée (Jaime, de Forges) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 6 July

1859 Geneviève de Brabant (Tréfeu) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 19 November

1860 Daphnis et Chloë (Clairville, Jules Cordier) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 27 March

1860 Barkouf (Scribe, Henry Boisseaux) Opéra-Comique 24 December

1861 La Chanson de Fortunio (Crémieux, Halévy) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 January

1861 Le Pont des soupirs (Crémieux, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 23 March

1861 M Choufleuri restera chez lui le … (`Saint-Remy’, Crémieux, Halévy) 1 act Présidence du Corps-legislatif 31 May, Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 14 September

1861 Apothicaire et perruquier (Élie Frébault) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 17 October

1861 Le Roman comique (Crémieux, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 10 December

1862 Monsieur et Madame Denis (Laurençin, Michel Delaporte) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 11 January

1862 Le Voyage de MM Dunanan père et fils (Paul Siraudin, Moinaux) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 23 March

1862 Les Bavards (ex-Bavard et Bavarde) (Charles Nuitter) 1 act Ems 11 June, revised version in 2 acts Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 20 February 1863

1862 Jacqueline (Crémieux, Halévy) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 14 October

1863 Il Signor Fagotto (Nuitter, Tréfeu) 1 act Ems 11 July

1863 Lischen et Fritzchen (Paul Boisselot) 1 act Ems 21 July, Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 January 1864

1864 L’Amour chanteur (Nuitter, Ernest L’Épine) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 5 January

1864 Die Rheinnixen (Nuitter, Tréfeu) Hofoper, Vienna 4 February

1864 Les Géorgiennes (Moinaux) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 16 March

1864 Jeanne qui pleure et Jean qui rit (Nuitter, Tréfeu) 1 act Ems 19 July; Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 November 1865

1864 Le Fifre enchante (aka Le soldat magicien) (Nuitter, Tréfeu) 1 act Ems 9 July; Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 30 September 1868

1864 La Belle Hélène (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 17 December

1865 Coscoletto (aka Le Lazzarone) (Nuitter, Tréfeu) Ems 24 July

1865 Les Bergers (Crémieux, Gille) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 11 December

1866 Barbe-bleue (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 5 February

1866 La Vie parisienne (Meilhac, Halévy) Palais-Royal 31 October

1867 La Grande-Duchesse [de Gérolstein] (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 12 April

1867 La Permission de dix heures (Mélesville, P Carmouche) 1 act Ems 9 July; Théâtre de la Renaissance, 4 September 1873

1867 Le Leçon de chant electromagnétique (Bourget) 1 act Ems August

1867 Robinson Crusoe (Eugène Cormon, Crémieux) Opéra-Comique 23 November

1868 Le Château à Toto (Meilhac, Halévy) Palais-Royal 6 May

1868 L’Île de Tulipatan (Henri Chivot, Alfred Duru) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 30 September

1868 La Périchole (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 6 October

1869 Vert-Vert (Meilhac, Nuitter) Opéra-Comique 10 March

1869 La Diva (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 22 March

1869 La Princesse de Trébizonde (Nuitter, Tréfeu) Baden-Baden 31 July; Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, 7 December

1869 Les Brigands (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 10 December

1869 La Romance de la Rose (Tréfeu, Jules Prével) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 11 December

1871 Boule de neige revised Barkouf Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 14 December

1872 Le Roi Carotte (Victorien Sardou) Théâtre de la Gaîté 15 January

1872 Fantasio (Paul de Musset) Opéra-Comique 18 January

1872 Fleurette (Trompeter und Näherin) (de Forges, Laurençin)1 act Carltheater, Vienna 8 March

1872 Der schwarze Korsar (Nuitter, Tréfeu) Theater an der Wien, Vienna 21 September

1873 Les Braconniers (Chivot, Duru) Théâtre des Variétés 29 January

1873 Pomme d’api (William Busnach, Halévy) 1 act Théâtre de la Renaissance 4 September

1873 La Jolie Parfumeuse (Crémieux, Ernest Blum) Théâtre des la Renaissance 29 November

1874 Bagatelle (Crémieux, Blum) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 21 May

1874 Madame l’Archiduc (Albert Millaud, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 31 October

1874 Whittington (H B Farnie) Alhambra, London 26 December

1875 La Boulangère a des écus (Meilhac, Halévy) Théâtre des Variétés 19 October

1875 La Créole (Millaud, Meilhac) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 November

1875 Le Voyage dans la lune (Eugène Leterrier, Albert Vanloo, Arnold Mortier) Théâtre de la Gaîté 26 October

1875 Tarte à la crème (Millaud) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 14 December

1876 Pierrette et Jacquot (Jules Noriac, Gille) 1 act Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 13 October

1876 La Boîte au lait (Grangé, Noriac) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 3 November

1877 Le Docteur Ox (Mortier, Gille) Théâtre des Variétés 26 January

1877 La Foire Saint-Laurent (Crémieux, Albert Saint-Albin [Ernest Blum, uncredited]) Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques 10 February

1878 Maître Péronilla (Offenbach, Nuitter, Paul Ferrier) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 13 March

1878 Madame Favart (Chivot, Duru) Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques 28 December

1879 La Marocaine (Ferrier, Halévy) Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens 13 January

1879 La Fille du tambour-major (Chivot, Duru) Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques 13 December

1880 Belle Lurette (Blum, Édouard Blau, Raoul Toche) Théâtre de la Renaissance 30 October

1881 Mademoiselle Moucheron (Leterrier, Vanloo) 1 act Théâtre de la Renaissance 10 May

Memoirs:

Offenbach en Amerique: Notes d’un musicien en voyage (Calmann-Levy, Paris, 1877)

Biographies and literature:

Schneider, L: Offenbach (Librairie Académique Perrin, Paris, 1923), Martinet, A: Offenbach (Dentu, Paris, 1887), Decaux, A: Offenbach (Pierre Amiot, Paris, 1958), Brindejoint-Offenbach, J: Offenbach, mon grand-père (Plon, Paris, 1940), Faris, A: Jacques Offenbach (Scribner, New York, 1980), Pourvoyeur, R: Offenbach (Editions du Seuil, 1994), Dufresne, C: Offenbach ou la gaîté parisienne (Criterion, Paris, 1992), Dufresne, C: Offenbach ou la joie de vivre (Perrin, 1998),Schipperges, T; Dohr, C; and Rüllke, K: Bibliotheca Offenbachiana (Verlag Dohr, Cologne, 1998), Hawig, P: Jacques Offenbach: Facetten zu Leben und Werk (Verlag Dohr, Cologne, 1999), Harding, J: Jacques Offenbach: A Biography (John Calder, London, 1980), Brancour, R: Offenbach (Henri Laurens, Paris, 1929), Rissin, D: Offenbach ou le rire en musique (Fayard, 1980),

Moss, A and Marvel, E: Cancan and Barcarolle: Life and Times of Jacques Offenbach (Exposition Press, New York, 1954), Kracauer, S: Orpheus in Paris: Offenbach and The Paris of His Time (Knopf, New York, 1938), Renaud, M and Barrault, J-L (ed.): Le Siècle d’Offenbach (René Julliard, Paris, 1959), Schneidereit, O: Jacques Offenbach (VEB Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig, 1966),Yon, J-C: Offenbach (Bigraphies Gallimard, Paris, 2000), etc.