Emese Lengyel

Széchenyi István University (Győr, Hungary)

17 August, 2025

At the beginning of the 20th century, a Singspiel, János vitéz, premiered at the Király Theatre and became a milestone of Hungarian musical literature. Hiding in the shadow of the successful, the entire oeuvre of the author, Pongrác Kacsóh, is also considered an essential part of Hungarian theatre history and musical literature produced at the beginning of the 20th century.

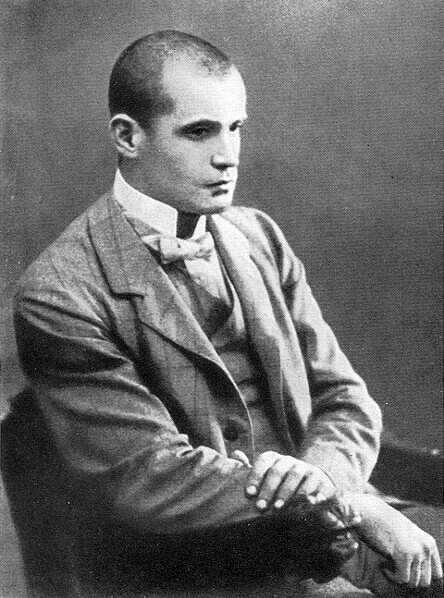

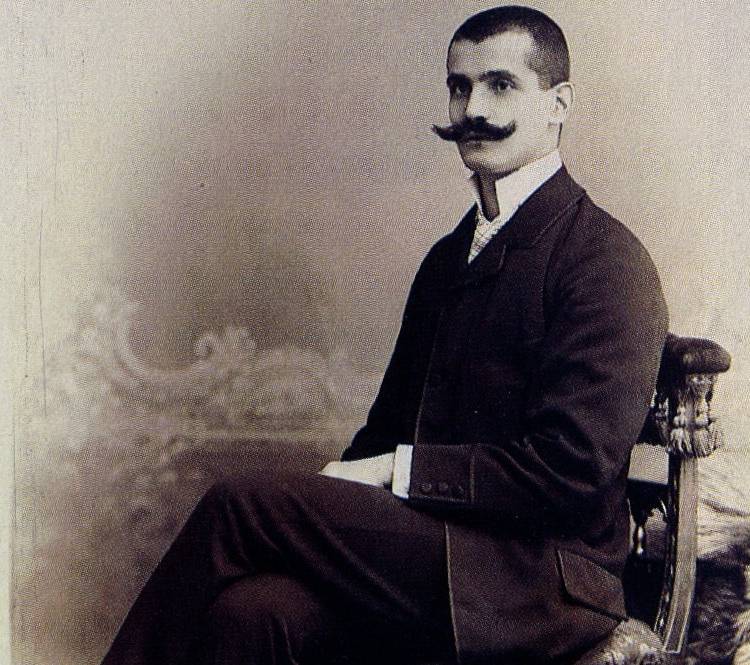

Pongrác Kacsóh in 1900. (Photo: Unknown)

The young Pongrác Kacsóh (1873–1923) [1], nicknamed Gráci, spent the second half of his high school years in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca, today in Romania), acquiring a significant amount of his musical knowledge there, such as learning to play the piano and the flute. Ödön Farkas (1851–1912) [2], composer and teacher, director of the Cluj Conservatory, introduced him to the art of music in greater depth.

However, Kacsóh did not only achieve success in the field of art, and at first, he was not even predicted to have a great career in the world of melodies, as he excelled in the sciences of mathematics and physics as well. He went to university in Cluj and obtained his doctorate in 1896. [3] In 1984, historian Elek Csetri published a comprehensive article about his secondary and higher studies [4], in which he relied heavily on Kacsóh’s university notes. All the awards Pongrác Kacsóh received which are noted in Csetri’s article, were complemented with significant monetary rewards and were won through competitions.

Despite that, the author also mentions that it quickly became apparent to Kacsóh’s masters that the young man possessed outstanding knowledge not only in the field of physics but also in music, as Csetri remarks, “in terms of [Kacsóh’s] artistic development, it is not without importance that he is remembered for his ‘beautiful… musical knowledge’ within the industry. Thus, he moved towards this direction at the end of his ‘proper’ university studies, in the 1894-95 academic year, since, at that time, he only participated in physics-related and musical competitions, testing his knowledge and preparedness. Among the questions related to his fields, a topic that required individual research and experimentation appeared repeatedly, in which a ‘physical phenomenon or group of phenomena’ had to be described.

The winner of the 100 HUF entry fee was senior-year Pongrác Kacsóh, who researched ‘electrical vibrations’ under the title L’importance de la question…, making ample use of the results of foreign research on the topic. The committee that evaluated the work also added that “[a]t the end, the applicant reports some of his experiments in the direction as well as their results, and finally, he provides a summary of the development of the theory regarding these phenomena.” [5] In the meantime, Kacsóh also obtained his teaching certificate, so he continued his career as a teacher, however, not in Cluj, but in Budapest (“[o]n September 15, 1897, Kacsóh Pongrác gained a teacher’s certificate, and based on this, in 1898, he began teaching at the District 8 State High School” [6]). Urban legend or not, he is known today as a strict teacher.

The path leading to his first Singspiel

The young high school teacher felt at home in the art scene of the capital city, so it is not surprising that many of his contemporaries noted that Kacsóh was a regular at opera performances and concerts. He also took music composition lessons from Academy of Music teacher Viktor Herzfeld (1856–1919) [7], who taught, among others, the defining authors of Hungarian operettas, such as Pál Ábrahám, Ákos Buttykay and Jenő Huszka.

However, a fate-altering event occurred soon enough, where Kacsóh was able to present himself to the public as composer. “His desire to develop some kind of musical activity became stronger, and in order to increase his technical experience, he took a job as a music teacher at Málnai’s well-known girls’ educational institution. The constant music occupation soon led to the development of Kacsóh Pongrác’s true vocation,” [8] noted his colleague, composer Béla Szabados (1867–1936) [9], in 1930. Kacsóh’s career as a composer may have begun partly with the trust of László Beöthy (1873–1931) [10], an influential journalist and theatre director of the Pest theatre scene.

The antecedent of this milestone is none other than Kacsóh’s first song play, Csipkerózsika [Sleeping Beauty], which, among others, writer, journalist and colleague Árpád Pásztor (1877–1940) [11] remembered in the columns of Pesti Napló in 1931 as follows: “March 25, 1904 – the early spring bustle in front of the Málnai girls’ institute of Gyár utca. Parents, students, and acquaintances arrive on rubber-wheeled fiacres, and on jolting, horse-drawn cabs, pedestrians smiling, and the ladies are in long dresses with leg of mutton sleeves and narrow waists, cut to emphasize the figure, and wide hats loaded with feathers and flowers on their heads, silk stockings on the legs sticking out from under the skirts are a great rarity… there is Miss Silbermann, the headmistress, welcoming the guests excitedly, including Superintendent László Torkos – all waiting for today’s institute performance, the arithmetic and singing teacher, dr. Kacsóh Pongrác wrote a play, and he also composed the music for it… The play is titled Sleeping Beauty and its music is rather lovely.” [12]

The institute performance was attended by Aurél Kern (1871–1928)[13], journalist of Budapesti Hírlap and composer (later, between 1915 and 1917, director of the Opera House) alongside János Csiky (1873–1917) [14], music writer and composer, also a student of Ödön Farkas. [15] Through them, László Beöthy, who had been the director of the Király Theatre since November 1903, was able to spread the word about the talented composer, even though the first season did not bring the much-awaited success for his theatre. [16]

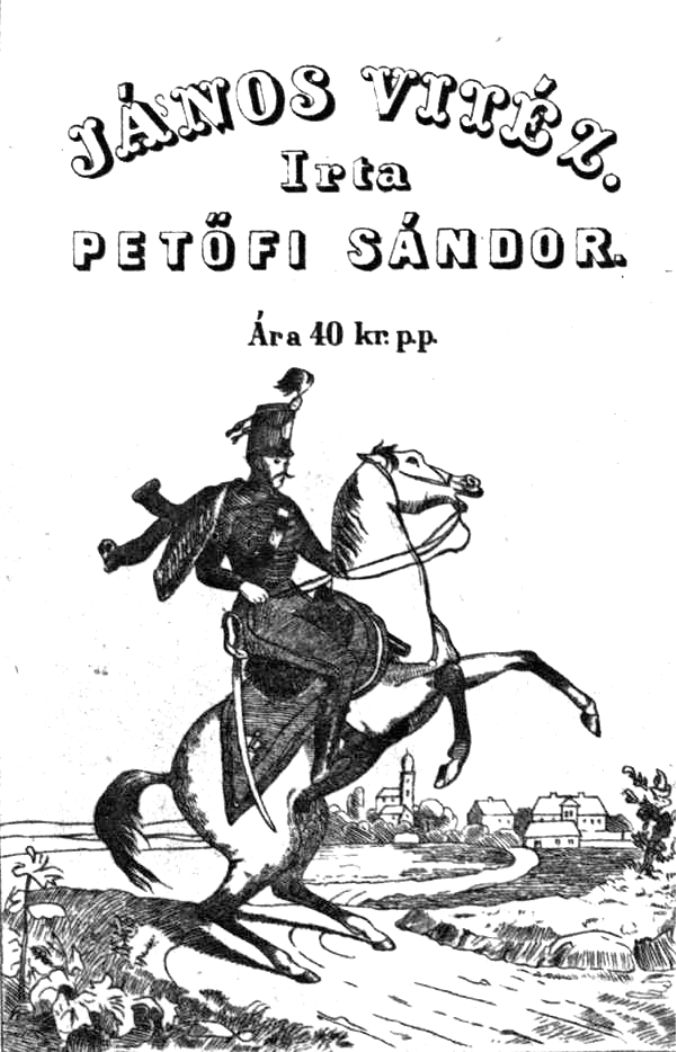

The original cover to “János vitéz”. (Drawing by Soma Orlai Petrich)

However, the golden age of the Király Theatre began on November 18, 1904 with the Singspiel János vitéz, which is due to Pongrác Kacsóh and his co-authors, Károly Bakonyi (1873–1926) [17] and Jenő Heltai (1871–1957) [18] as “Kacsóh was commissioned by Károly Bakonyi, the author of the libretto of Bob herceg [Prince Bob], who asked Kacsóh to write music for Petőfi’s well-known narrative poem, János vitéz, a compulsory reading in the lower grades of high school. And the bohemian poet Jenő Heltai, struggling with constant financial problems, undertook to write the poems.” [19]

Famed Hungarian diva Sári Fedák (1879-1955).

The success proved to be rather overwhelming, with prima donna Sári Fedák in the title role, who formerly also proved herself in the title role of Prince Bob, that the other Kacsóh compositions did not even come close to the triumph of János vitéz.

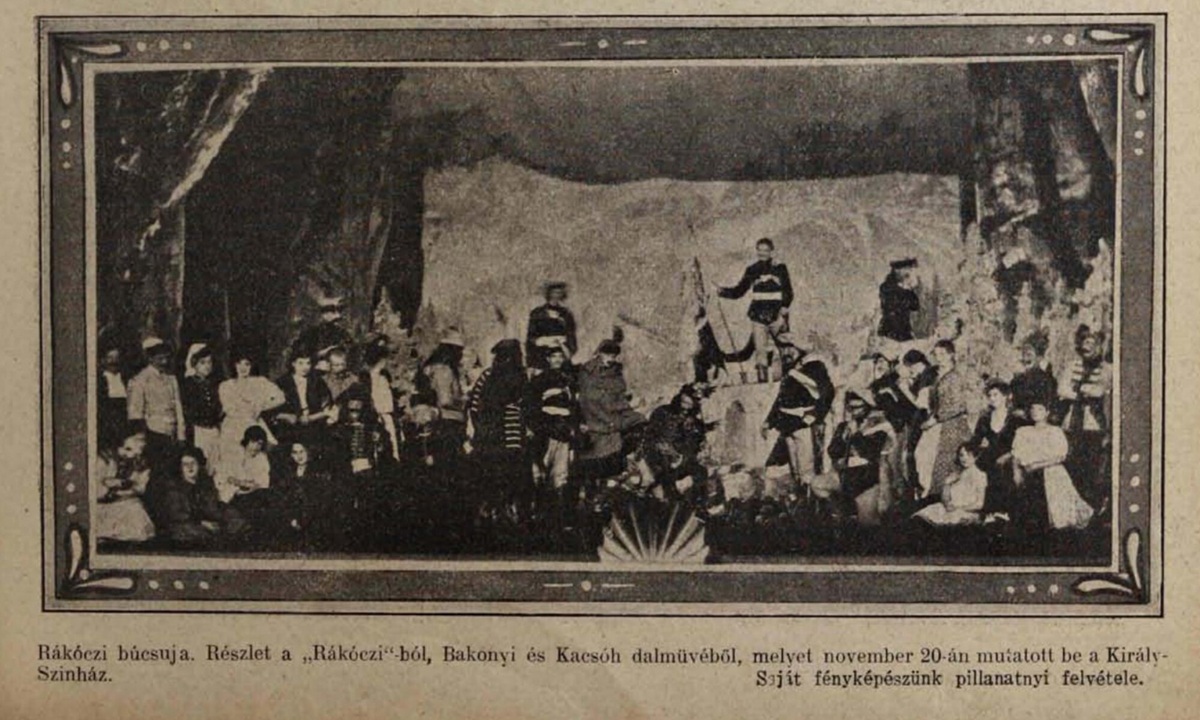

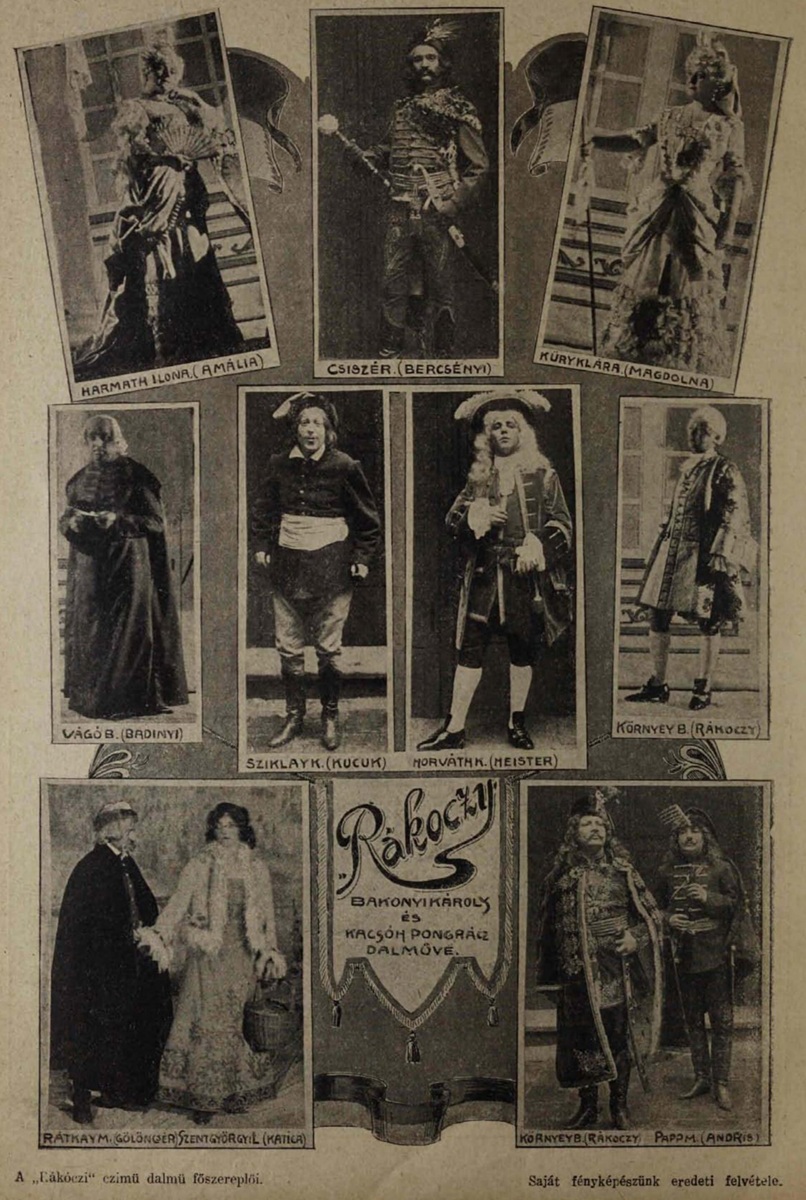

Two years later, in 1906, another Singspiel – titled Rákóczi – premiered in Király, the libretto of which was also authored by Károly Bakonyi, and, as a critic of Budapesti Hírlap noted, “after the sweet, naive directness of János vitéz, Rákóczi is bursting with power, awareness, certainty, with the omniscience of effect, using all kinds of shiny tools of modern knowledge. (…) Despite the widening of the range of his skills, despite the melodic power, warmth, intimacy and, above all, the Hungarianness of Kacsóh’s invention remained. He is a musical poet who truly, deep down, in his heartfelt source of inspiration, is Hungarian! One of those who did not artificially learn the language of Hungarian notes, who speak their sweet mother tongue, when the joy of a Hungarian rhythm bounces, the sweet pain of a Hungarian melody sobs in their music. In the small kuruc melodies of Rákóczi, we recognize the traces of the author of János vitéz, the constructed ensembles show the renowned, modern master” remarks the journalist, in a style that today’s reader would probably find corny. [20]

Scene from the play “Rákóczi”. (Photo: Tolnai Világlapja, 1906, Vol. 6, No. 49)

However, it is worth noting that Budapesti Hírlap was owned by Jenő Rákosi at the time, and Rákosi was Beöthy’s uncle, Beöthy himself starting his journalistic career at this press outlet. Thus, praising the performance of the Király Theatre and Kacsóh was far from without interest. For instance (hoping that the author of the present study is not regarded as biased by any means), a journalist of Pesti Hírlap had a completely different view of the Rákóczi performance, remarking that “[...] Rákóczi not only could not catch up to the success of János vitéz but remained behind several of his ‘comrades’.” [21] Moreover, not only the music of the play was criticized, but also the story received a negative review from Pesti Hírlap.

Cast of “Rákóczi”. (Photo: Tolnai Világlapja, 1906, Vol. 6, No. 49)

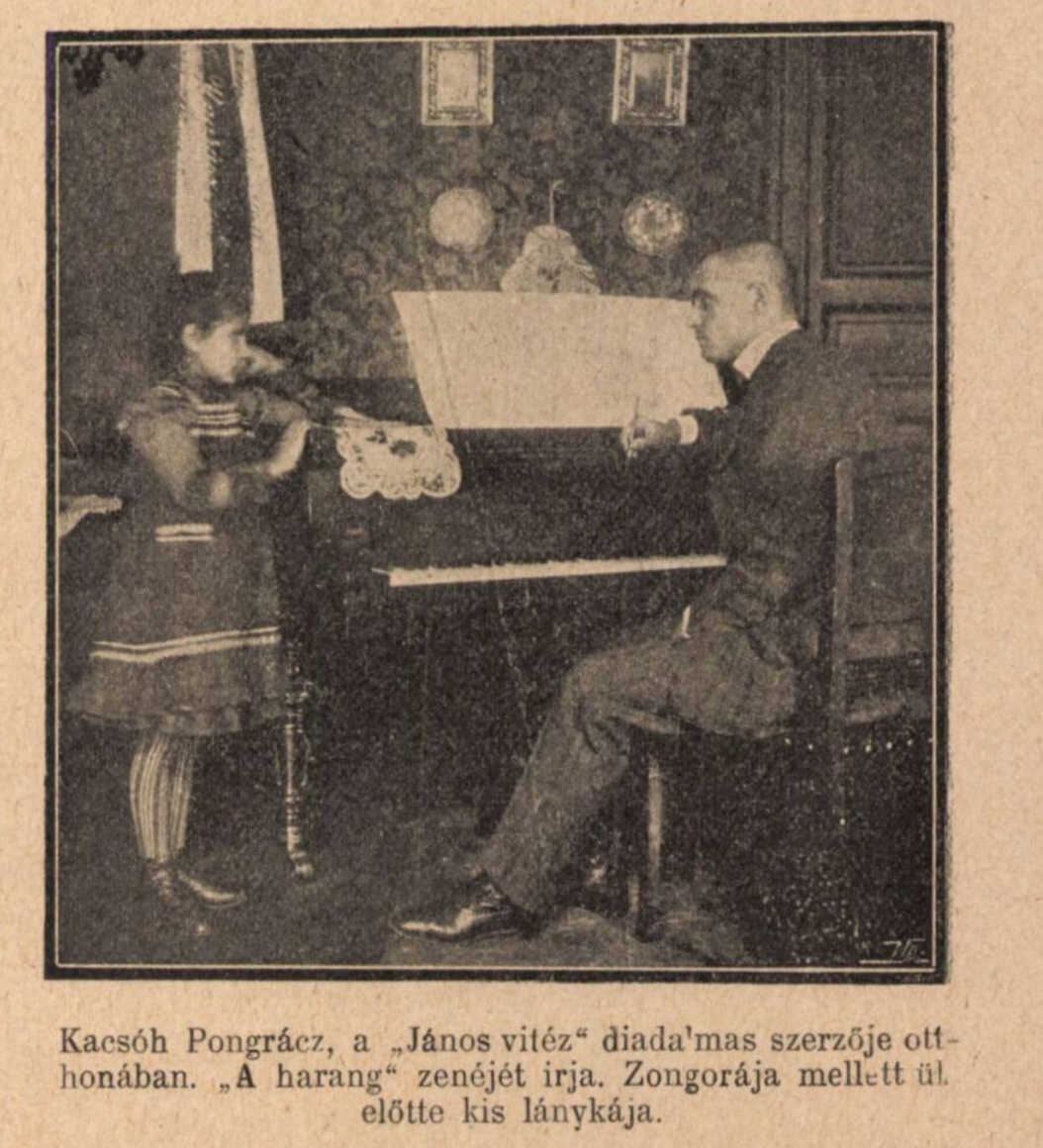

Although Kacsóh himself did not produce an original musical piece in 1907, he and Ákos Buttykay (1871–1935) [22] wrote accompanying music for Árpád Pásztor’s work, titled A harang [The Bell]. “The premiere of the three-act legend A harang took place on February 1, 1907, at the Király Theatre. [...] The critics remember it as having ear-catching, ‘audience-friendly’ music [...]” [23] Besides, Kacsóh also composed songs for Ferenc Molnár’s works, Fehér felhő [White cloud] and Liliom. [24]

Composer Pongrác Kacsóh writing the score for A harang. (Photo: Tolnai Világlapja, 1907, Vol. 7, No. 5)

Then, in 1908, Kacsóh undertook to present his work again, as his operetta Mary-Ann was staged in Beöthy’s theatre. The play of the British author Israel Zangwill (1864–1926) [25] was adapted for the Hungarian stage by playwright and critic Sándor Hajó (1876–1944) [26], for which the writer and journalist Andor Gábor (1844–1953) [27] wrote poems. This operetta tale is lesser known and was quickly forgotten about, although, if one is to believe the criticism published in Budapesti Hírlap, both the work itself and the performance were characterized by ‘sincere naivety,’ as “[t]he lovely, tender enamel of the fairy tale and its naivety shines unharmed through the piece in its new form, praising Sándor Hajó’s work to its extremes. Had that all been lost, the effect could not have been as deep and harmonious as it has flowed from the hearts tonight. The music of Pongrác Kacsóh is quite like the main concept of the play: soft, dreamy, flowy and moving. The music of romantic dreams. There is some great purity in it, incapable of receiving any other feeling than those of the similarly pure, beautiful, and elevated.” [28]

Cast of the play “Mary-Ann”. (Photo: Magyar Színpad, 1908, Vol. 11, No. 343)

In 1911, Kacsóh composed the accompanying music for the Hungarian stage adaptation of Maurice Maeterlinck’s A kék madár [The Blue Bird]. [29] Besides, he also produced a Singspiel (song play) titled Pityergő, for the cabaret stage, the premiere of which was held on April 9, 1914, at the Medgyaszay Kabaré (the former Modern Színpad). [30] Moreover, in 1914, he even composed the soundtrack for Mihály Kertész’s movie, [31] Az aranyásó [The Gold Digger]. [32]

His last work is entitled Dorottya, which was based on the Csokonai epic. It was possible to read about Kacsóh’s Dorottya as early as 1916 and 1917 since Színházi Élet published articles about opera house performances and comedy operas of the time. [33] Then, in 1919, the contemporary press was sure that the Király Theatre would host the new Kacsóh Singspiel (song play). [34] The work was finally presented long after the composer’s death, in January 1929, at the City Theatre in Szeged. At the premiere, amongst others, László Beöthy delivered a speech in which he celebrated the rebirth of rural acting. [35]

His role as a music teacher and in public life

Zenevilág [36] (a theatre, musical and musical literature weekly) was published between 1900 and 1916 in Hungarian and German [37], its editor-in-chief and owner was Lajos Hackl N., and from November 1902, from vol. III, no. 13, Kacsóh joined Hackl as editor-in-chief. [38] In 1909, Kacsóh started teaching again, albeit because of a ministerial decree. He worked as the director of the real school in Kecskemét until 1912, and despite his duties as a teacher, he was an active player in the town’s musical life.

Then, between 1912 and 1922, duty called him to Budapest again: in December 1911, at the invitation of the capital, Pongrác Kacsóh undertook municipal service and began working as a music lecturer. Here, he organized the lower-level district music courses, and then, by setting up the middle- and higher-level departments, he also expanded music education in the capital’s schools completely. [39]

Another portrait of Pongrác Kacsóh. (Photo: Unknown)

The backbone of the music poet’s work were those music pedagogy and historical works that he published continuously from 1904. He was a member of the Országos Magyar Zenész Szövetség [National Association of Hungarian Musicians] and later worked as its president for a year. Based on the minutes published in the Magyar Zenészek Lapja by the Association, it becomes evident that Kacsóh was unanimously elected president at the regular general meeting on March 21, 1913. [40] “[...] in his speech, he thanks you for the trust that placed him at the head of the association and promises that, given his talent, he will always strive to promote the material and moral well-being of Hungarian musicians. His busy schedule does not allow him to continuously participate in the association’s administrative tasks, however, whenever the interest of the association so requires and in more important matters affecting the association, he will strive to benefit the National Association of Hungarian Musicians with his operation. He, thus, accepts his election” [41] – despite these, Kacsóh was only able to fulfil the promises made in this speech for a short time, as he resigned from the position after one year citing his busy schedule.

“The National Association of Hungarian Musicians, as the Hungarian department of the International Association of Musicians, elected music director Elemér Sereghy into the place of Dr Pongrác Kacsóh as president”, [42] as the results of the association’s regular annual general meeting were announced in A Zene on April 10, 1914. [43]

Still, Kacsóh was not only a composer, editor, teacher and artist holding the most diverse positions. In 1913, he married Georgina Flóra Rózsa Nagy, and, although they parted ways later in 1917, a son was born from their marriage, whose parents named him János. Ultimately, what would Pongrác Kacsóh name his son after, if not the ‘crown jewel’ of his career, János vitéz?

After the composer died in 1923, the boy’s guardian became his friend and former best man, theatre director László Beöthy, who paved the way for János vitéz and all Kacsóh compositions. “Nineteen years ago, a new theatre, a young actress and a young poet met. The future of Hungarian theatre, the extraordinary career of a great artist and your immortality were born out of this meeting. The place of this meeting was the Király Theatre, from the moment you set foot there, it was not your second, but your first, true home, the locus of your enthusiasm, the cheerleader of your joys, the comforter of your sorrows, the trumpeter of your talent, the servant of your fiery mind…” [44] – said Beöthy at Pongrác Kacsóh’s funeral, and it seems that the theatre director’s intuition proved to be correct, as the name of the composer and his greatest work still sound familiar to all of us today.

[1] Székely, György, ed. “Kacsóh Pongrác.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Budapest, Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 347. An article about the composer in English was written by Kurt Gänzl, see Gänzl, Kurt. The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre: Second Edition. Vol. 2. New York, Schirmer Books, 2001, p. 1047.

[2] Székely, György, ed. “Farkas Ödön.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. 1994, p. 204.

[3] The authors frequently cite the year 1897. However, as the author’s doctoral dissertation was printed in Cluj in 1896, I opted for using the earlier date in the present essay. The title of the doctoral dissertation is Az egyenlőségi és egyenlőtlenségi elv viszonya a mechanikában [The Relationship Between the Principles of Equality and Inequality in Mechanics].

[4] Csetri, Elek. “Kacsóh Pongrác tanulmányai Kolozsváron” [“The Studies of Kacsóh Pongrác in Cluj”]. Nyelv- és Irodalomtudományi Közlemények [Linguistic and Literary Studies], Vol. 28, No. 2, 1984, pp. 141–146.

[5] Csetri, Elek. “Kacsóh Pongrác tanulmányai…” [“The Studies of Kacsóh Pongrác in Cluj”], p. 145.

[6] Szabados, Béla. “Kacsóh Pongrác.” Muzsika, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1930, p. 61.

[7]https://www.arcanum.com/hu/online-kiadvanyok/Lexikonok-magyar-eletrajzi-lexikon-7428D/h-75B54/herzfeld-viktor-75D84/(Accessed July 29, 2022)

[8] Szabados, Béla. “Kacsóh Pongrác.” Muzsika, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1930, p. 61.

[9] Székely, György, ed. “Farkas Ödön.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 710.

[10] Székely, György, ed. “Beöthy László.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 84.

[11] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 597.

[12] Pásztor, Árpád. “Csipkerózsikából János vitéz. Hogyan került színre Kacsóh Pongrác?” [“From Sleeping Beauty to János vitéz: How Kacsóh Pongrác’s Work Was Adapted to the Stage.”] Pesti Napló, Vol. 82, No. 260, 15 Nov. 1931, p. 20.

[13]https://mek.oszk.hu/02100/02139/html/sz13/278.html (Accessed July 31, 2023)

[14]https://mek.oszk.hu/08700/08756/html/I/szin_I.0351.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2023)

[15] Pásztor, Árpád. “Csipkerózsikából János vitéz. Hogyan került színre Kacsóh Pongrác?” [“From Sleeping Beauty to János vitéz: How Pongrác Kacsóh’s Work Was Adapted to the Stage.”] Pesti Napló, Vol. 82, No. 260, 15 Nov. 1931, p. 20.

[16] Székely, György, ed. “A Király Színház.” In Magyar Színháztörténet II. 1873–1920 [Hungarian Theatre History II. 1873–1920]. Magyar Könyvklub – Ország Színháztörténeti Múzeum és Intézet, 2001, p. 610.

[17] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 43.

[18] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 297.

[19] Ibid., p. 610.

[20] “Rákóczi.” Budapesti Hírlap, Vol. 26, No. 321, November 22, 1906, p. 12.

[21] “Rákóczi.” Pesti Hírlap, vol. 28, no. 321, November 21, 1906, p. 8.

[22] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 123.

[23] Lengyel, Emese. “‘Operettet, én?… Soha!… Nem is értek hozzá!…’ – Egy elfeledett operettkomponista, Buttykay Ákos (1871–1935) munkásságának nyomában” [“’Operetta and Me? ... Never!... I Don’t Even Understand It!’: On the trail of a forgotten operetta composer, Ákos Buttykay (1871–1935)”]. Szkholion, Vol. 20, No. 1–2, 2022, pp. 89–99.

[24] Szabados, Béla. Kacsóh Pongrác… p. 62.

[25]Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Israel-Zangwill. Accessed August 7, 2023.

[26] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 280.

[27] Székely, György, ed. “Pásztor Árpád.” In Magyar Színházművészeti Lexikon [Hungarian Theatre Art Encyclopaedia]. Akadémia Kiadó, 1994, p. 240.

[28] “Mary-Ann.” Budapesti Hírlap, Vol. 28, No. 292, December 6, 1908, p. 15.

[29] N.a. “Kék madár” [“The blue bird”]. Színházi Élet, Vol. 2, No. 36, November 19, 1911, p. 18.

[30] Alpár, Ágnes, ed. A cabaret – A fővárosi kabarék műsora 1901–1944 [The Cabaret – The Programmes of the Capital City Cabarets 1901–1944]. Budapest, MSZI, 1978, p. 97.

[31] Az aranyásó [The gold digger]. Hangosfilm/Sound film, https://www.hangosfilm.hu/filmografia/az-aranyaso. (Accessed July 31, 2023)

[32] “Az aranyásó” [“The gold digger”]. Színházi Élet, Vol. 3, No. 13, March 29, 1914, p. 5.

[33] N.a. “Új magyar opera” [“A new Hungarian opera”]. Színházi Élet, Vol. 5, No. 24, November 26, 1916, p. 24.

[34]n.a. “Kacsóh Pongrác…” Színház Élet, Vol. 8, No. 43, October 29, 1919, p. 38.

[35] Stella, Adorján. “A szegedi Dorottya-banketten a vidéki színészet újjászületését ünnepelték.” [“At the Szeged Dorottya Banquet, the Rebirth of Provincial Theatre Was Celebrated”]. Színházi Élet, Vol. 19, No. 4, January 20, 1929, pp. 30–32.

[36] This should not be confused with the similarly titled journal Zenevilág, which was published from 16 Dec. 1890 to 15 July 1891. For more on this, see Kárpáti, János. “Zenevilág (1890–1891).” https://ripm.org/pdf/Introductions/ZENintroor.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2022)

[37]Zenevilág (1900–1916). https://www.ripm.org/?page=JournalInfo&ABB=ZSZ. Accessed July 29, 2022.

[38] “A Zenevilág” [“The Music World”]. Pesti Hírlap, Vol. 15, No. 21, January 21, 1903, p. 6.

[39] Szabados, Béla. Kacsóh Pongrác… p. 63.

[40] N.a. “Jegyzőkönyv” [“Minutes”]. Magyar Zenészek Lapja, vol. 10, no. 8, April 15, 1913, p. 5.

[41]Ibid., p. 5.

[42]N.a. “Az Országos Magyar Zenés Szövetség…” [“The National Association of Hungarian Musicians...”]. A Zene, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1914, p. 83.

[43] N.a. “Jegyzőkönyv” [“Minutes”]. Magyar Zenészek Lapja, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 3.

[44] Beöthy, László. “Kacsóh Pongrác, Isten veled” [“Farewell to Kacsóh Pongrác”]. Színházi Élet, Vol. 13, No. 53, December 29, 1923, p. 8.