Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 October, 2014

The German journalist Klaus Waller has written a 240 pages biography of Paul Abraham: Der tragische König der Operette. It is the first full-length bio of the superstar of Weimar Republic jazz operetta, who was driven out of German immediately by the Nazis in 1933. Because his hits – Viktoria und ihr Husar (1930), Blume von Hawaii (1931) and Ball im Savoy (1932) – were seen as the pinnacle of degeneration. We caught up with Mr. Waller to discuss his new book.

Journalist and biographer Klaus Waller. (Photo: Privat)

You are not only an experienced author, but also an experienced biographer who has – among other things – written a biography of former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder. What drew you to Abraham?

Years ago, my local newspaper ran an article on the fate of Paul Abraham whose melodies I knew from my childhood. The episode in which he conducts an imaginary orchestra in the middle of New York’s traffic – completely out of his mind – fascinated me. During my work for Wikipedia, where I wrote many articles about people who had been persecuted by the Nazis, I realized how little information was available on Abraham’s life and career. So I started researching.

Scene from the 1932 movie version of “Blume von Hawaii” starring Marta Eggerth.

Is there anything “political” about Abraham that links this new book with your previous work?

I had been busy before studying subjects from the Weimar Era and the dramatic consequences these people faced once the Nazis came to political power. In addition, I am first and foremost a journalist. I am always interested in politics, no matter whether we are talking about the political situation during the Weimar Republic or in a reunited Germany.

Abraham was the most successful operetta composer of the early 1930s, his Blume von Hawaii the single most successful show of the era. Why have there been no earlier attempts to write a biography of this once famous man?

Maurus Pacher and György Sebestyén both wrote about Abraham before. Pacher sketched a very brief overview, covering the then-known facts on Abraham. Sebestyén tried to get a grip of his subject by fictionalizing the story. What probably deterred several later authors is the fact that publishers regularly turn down the topic, as there seems to be too little interest in operetta per se, and Abraham in particular is claimed to be too unknown.

My own literary agent, who had previously sold many of my books, found the theme “totally unexciting” and refused to take action.

When you started your research: what were the most difficult parts of reconstructing Abraham’s life and career?

Pail Abraham at the hight of this career in the early 1930s.

The hardest thing was to discover that after so many years you cannot clarify many questions anymore. There are only some witnesses alive today, from Abraham’s last years in a Hamburg clinic. He himself was not able, at that point, to give any information on his life. From the glory days, i.e. the period before 1933 or even 1938, but also from the years in exile, there are no witnesses left after 80 years. Prior to me, János Darvas researched the life of Abraham for his Arte documentary film. The material he collected forms the Paul Abraham Archive of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. However, there is a clear focus on Abraham’s time in Hamburg in that archive, there are few items or documents from the earlier periods. Abraham kept no diary, and there are few original letters. There are some interviews, however. But you have to remember that Abraham staged himself as an “artist” in many of these.

He invented – like artists such as Joseph Beuys – large parts of his vita, with little concern for continuity.

It is absolutely amazing that his statements about his childhood, about the university days and about his alleged title of “professor,” his self-stylization as a child prodigy etc. have never been questioned before, although he constantly contradicts himself. But his statements fit the image of the brilliant artist who become an overnight sensation, and that’s the image many people still want to cherish.

Are there still any people around who could give first-hand testimony about Abraham’s wife?

There are, as far as I know, no living descendants of Abraham’s family. He had no children. What happened to Charlotte Abraham is not known to me. The important witnesses are, as I said, dead.

Paul Abraham and his wife Charlotte, in the Budapest days.

After decades of neglect, Abraham is experiencing a revival in recent years: the radio station in Cologne tried reconstructing the original orchestra material of the three famous Abraham operettas, the same reconstruction team (Hagedorn & Grimminger) are busy working on Abraham’s last European operetta, Roxy und ihr Wunderteam, for Dortmund right now, Gießen performed the supposedly “original” Viktoria und ihr Husar on stage, Blume von Hawaii is being produced at various places in Germany and Austria, and Barrie Kosky scored a major triumph with Ball im Savoy at the Komische Oper Berlin. Why do you think modern audiences are suddenly so fascinated by these works, when no one deemed them worth looking at for so many years before?

It probably needed an enthusiastic theatre director like Barrie Kosky to initiate this development with such wide-reaching effect. His production of Ball im Savoy managed to reach a cosmopolitan Berlin audience, just like Abraham himself did back in the late Weimar years. Still, the Abraham Renaissance – if you want to call it that – is only an insider phenomenon. Abraham’s music is not part of everyday culture anymore, not on the scale it was in the early 1930s and even in the 1950s and 1960s. In my youth, there was no radio station without regular programs featuring operetta melodies. There were also no television shows without “Operettenpotpourris.” Today, that is not the case anymore.

The reason Abraham is being rediscovered now by an entirely new generation is that his music is being perceived as “modern” and different to the nostalgic and old-fashioned style commonly associated with “Wiener Operette”.

Abraham is like a fresh breeze from a time that many – including young people – find particularly exciting.

Volker Klotz in his book Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst (1991/2004) labeled Abraham “degenerate” and worth forgetting. Did that have an impact on the way Abraham was perceived by the operetta world at the turn of the millennium?

The cover of Klaus Waller’s Abraham biography.

I will not get involved in theoretical musicological debates. My book is not a rehabilitation of Abraham’s music, but a description of his life. Whether Volker Klotz’s opinion on Abraham’s importance as an operetta composer is right or wrong is something others must decide. A small contribution regarding the evaluation of Abraham’s music comes from historian Klaus Peter Schumann who wrote the essay “Ein europäischer Gershwin?” I have included it in my book, as an extra, because musical analysis and evaluation are not part of my biographical text. But to answer your question: It could well be that Klotz’s verdict stopped many theatre people from looking closer at Abraham’s oeuvre.

That they did not take to trouble to form their own – independent – opinion, is sad and their loss.

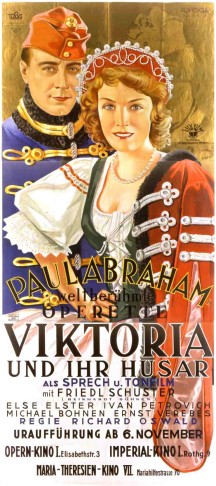

Poster for the movie version of Abraham’s “Viktoria und ihr Husar.”

Why does the damning verdict of guru Klotz suddenly not matter anymore?

The Zeitgeist cares little about such verdicts. The renaissance of operetta is only a tiny part of our newly found love with “Tralala,” as Kosky calls it. People are experiencing massive uncertainty because of the financial crisis and international conflicts that threaten their comfortable existence. For decades our attitude towards life was dominated by a feeling of immunity to crisis and war. This feeling has faded. Which might, incidentally, be an interesting parallel to the time when Abraham’s music first became so tremendously successful. It might explain why it has gained popularity again with today’s audiences.

When you listen to the various reconstructions of Abraham’s scores – in Cologne, Gießen, Berlin etc. – are there any modern day performances that match the original glory of Abraham?

That’s a question you should ask musicians. There are always trends and fashions, also in the way we play operetta: sometimes more schmaltzy, sometimes more jazzy. I cannot judge how difficult it is to play Abraham “originally,” I’m not a musician.

After Janos Darvas made his pioneering documentary movie about Abraham, various authors set out to write a biography. Your book is the first to actually come out, Karin Meesmann is busy finishing hers for publication in 2015. Did you contact the other biographers?

Arbaham rehearsing with Rózsi Bársony & Oszkár Dénes in Berlin, pre-1933.

I actually started work on my biography before I knew the Darvas film existed. The film was eventually broadcast at truly ridiculous late night times on television. I don’t see it as competition to my book, nor do I see Miss Meesmann as a competing author. I have spoken briefly with her, but that conversation did not lead to a cooperation, although I would have found that exciting. She comes from the field of music, I come from journalism. It would have been a perfect match, but it did not happen. Our two biographies will (hopefully) be very different and should complement each other.

Does Abraham’s life leave room for multiple interpretations?

There are so many gaps in Abraham’s life story, perhaps Miss Meesmann will have had better luck filling some of them. I would definitely welcome that. Especially the time between Abraham’s university days and his appearance on the international operetta scene. We are talking of exactly ten years. They are largely in the dark, to me. The few anecdotes that Abraham himself tells about this time are in my book, but there is a big question mark behind them. As I said, a lot of his stories are fiction. Once you discover that some of his statements are incorrect, you stop believing the rest.

The tragic fall of this briefly successful composer and the devastating fate of him being delivered to a mental hospital in New York and then flown back to Germany after the war in the so called “Airplane of the Damned” could be seen as Hollywood-worthy. Are there any plans to turn your book – or Abraham’s life story – into a movie, maybe with Adrian Brody as Pal Abraham?

Such plans definitely do not exist. But feel free to become active here.

Abraham being escorted off the airplane on this return to Germany, after WW2. He was taken directly to a hospital to be treated for syphilis.

Which episode in your biography of Abraham do you find the most touching?

The most fascinating and most shocking moment of his life is the crash after the exorbitant success in Berlin. You have to remember that he was a gambler, although a braggart. He predicted this success, jokingly, but probably never really expected it to happen. But then the triumph did come, over night, and he was the greatest star of the all. At first he could not believe this himself. And then, just as he reached the absolute top and accepted his new status, there comes the crash, caused by external forces. He never got over.

Last question: If you wanted to convince anyone of the glory of Abraham’s music, which number (and in which interpretation) do you recommend listening to?

I would suggest two songs. For the jazzy side of Abraham, “Do-do-do” with Oszkar Dénes, and for the romantic side, “Toujours l’amour” with Gitta Alpár. The versatility that is evident in these two compositions is what I personally love about Paul Abraham.

;

This interview and of course the biography itself are a very good introduction into the live and destiny of Paul Abraham. Its amusing to read, and you also get an impresseion of the way of live, that artist had in Berlin in the 20th and 30th.

Is there an English translation of Klaus Waller’s book planned?

Not that I know of.

I think the Germans’, certainly the Berliners’, taste in music and theatre did not change overnight because of Hitler in 1933. But was there an explicit ban on producing Abraham’s operettas and playing his music because he was Jewish?

The only work explicitly banned by the Nazis was “Der fidele Bauer” by Leo Fall. Because a state subsidy system was introduced for operetta in 1933, all theater director had to “discuss” there repertoire with the Reichsdramaturg, Dr. Rainer Schlösser. That made it easy for him to persuade those remaining in Germany which pieces were considered suitable, and which were not.

Thank you! The Nazi policy of “so oder so”. I know the new Reichsmusikkammar excluded Jewish composers, but the idea of a total and immediate theatre censure didn’t sound right to me. The jazz style of Abraham’s music seems to have lived on for a while despite it all, though it of course didn’t help Abraham. But the idea of happily mixing races (My golden baby, and the Mama from Yokohama) must have made the Reichsdramaturg angry, and Abraham’s librettists met a sad fate too, I believe.