Harry Forbes

Forbes on Film & Footlights

12 August, 2018

Enterprising Ohio Light Opera, ever devoted to ‘authentic’ productions from the world of musical comedy and operetta, seems to go from strength to strength each year, and this season was no exception with seven worthy productions including a peerless Candide which has to rank as a highlight of composer Leonard Bernstein’s centenary year. I was fortunate enough to be there during the fifth annual Festival Symposium week (July 31 – August 3) – Taking Light Opera Seriously – which meant that besides the seven mainstage musicals and operettas – The Pajama Game, Babes in Arms, Fifty Million Frenchmen, Iolanthe, La Périchole, Candide, and Cloclo, a real rarity – there were myriad lectures and special concerts further illuminating those productions and paying homage to OLO’s 40 years.

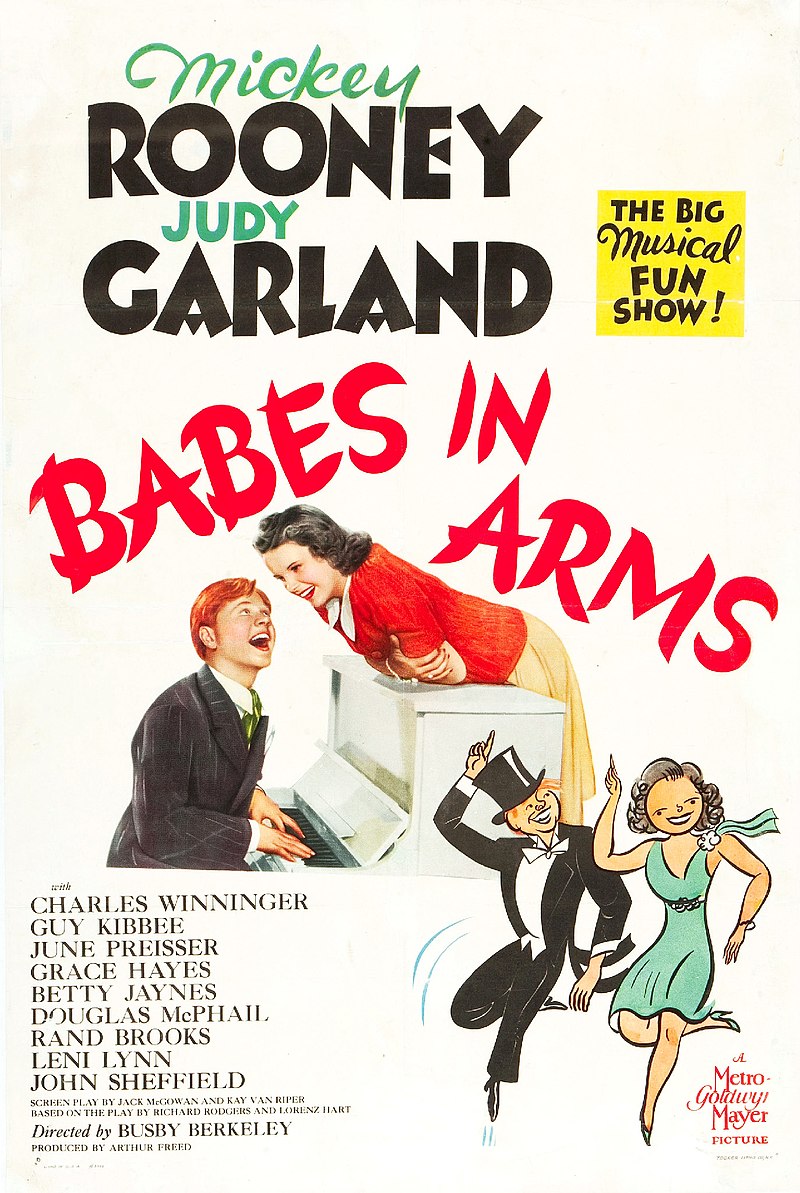

Scene from the 2018 Cole Porter production of “Fifty Million French Men” at Ohio Light Opera. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

As in previous seasons, I was struck by the high level of musicianship both in the pit and on the stage, the incredible versatility of the cast who can morph from ensemble player to varied leads with astonishing ease, and the integrity of the overall enterprise under the savvy leadership of Artistic Director Steven Daigle and Executive Director Laura Neill.

As indicated, adding fascinating depth to the shows during the symposium were Lehár biographer Stefan Frey from Munich, Offenbach expert Laurence Senelick of Tufts University [author of the recent Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture], Rodgers and Hart scholar Dominic Symonds from the University of Lincoln in the UK, and musical theater author and regular ORCA contributor Richard Norton who is based in New York, each offering witty and erudite background on the shows in their respective fields. The speakers are always well chosen, but this was an exceptionally interesting group.

The participants of the Festival Symposium (“Taking Light Opera Seriously”: Mike Miller, Laurence Senelick, Richard C. Norton, Dominic Symonds, and Stefan Frey. (Photo: Paul Drooks)

Daigle kicked off the week by asking how each of the speakers came to his interest in musical theater, and the answers were varied. Senelick’s first love was Gilbert and Sullivan, until he discovered the rather more intriguing sex appeal of the Offenbach works. Norton grew up in Boston, once the big tryout town for Broadway musicals, and thus got to see many works in their nascent form. Symonds’ boredom with Sunday school choir led to his being offered a role in a local production of Oliver. And Frey got hooked on Lehár when he heard the Merry Widow waltz in, of all things, Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days.

In a special operetta film presentation, OLO board chairman Michael Miller, the master organizer of the symposium (with invaluable help from wife Nan), presented a series of well chosen video clips culled from the company’s 141 show titles. Vintage excerpts demonstrated the consistent quality of the company going back as far as 1984 with such productions as Merrie England, The Firebrand of Florence, and Robin Hood. So, too, there were some bittersweet clips of the late, much loved tenor Brian Woods and others who have since passed on.

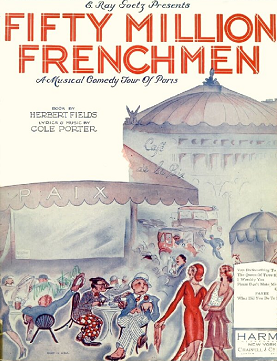

Poster for the 1939 MGM film version of “Babes in Arms” starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney.

To begin with the musicals, Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms with its treasure trove of standards and a rather flimsy but, in Rodgers’ own words, “serviceable book,” received first-class treatment. Sarah Best had just the right breezy insouciance as grifter Billie, and handled the standards “Where or When,” “My Funny Valentine” and “The Lady is a Tramp” (with its multiple encore verses) with requisite style. The phenomenal Alexa Devlin – a vocal and dramatic chameleon – knocked “Johnny One-Note” and her other numbers out of the park.

Benjamin Krumreig and Gretchen Windt socked over “I Wish I Were in Love Again” and “You Are So Fair” with period perfect aplomb. And Spencer Reese not only scored in his role as the lead “babe” Val but provided resourceful choreography for the show including the lengthy “Peter’s Journey” ballet with nifty hoofing from Timothy McGowan and Hannah Kurth (choreographed originally by the great George Balanchine). In fact, it should be noted that Reese’s imaginative dances for all the productions has helped OLO considerably up its game across the board.

Sarah Best and Spencer Reese in the 2018 production of “Babes in Arms” at Ohio Light Opera. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

The number originated by the Nicholas Brothers, “All Dark People Are Light on Their Feet” was shorn of its prefix as in its New York Encores revival and simply presented as “Light on Our Feet,” with good hoofing by DeShaun Tost and Adam Kirk as the black brothers whose appearance in Val’s show is almost thwarted by a Southern bigot.

Symonds’ pre-show lecture, crisply delivered with apt visuals (like the other speakers), described the circumstances of how Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart met, and their early work on such shows as Fly With Me (1920) and The Garrick Gaieties (1925) which would already bear the hallmarks of their later work.

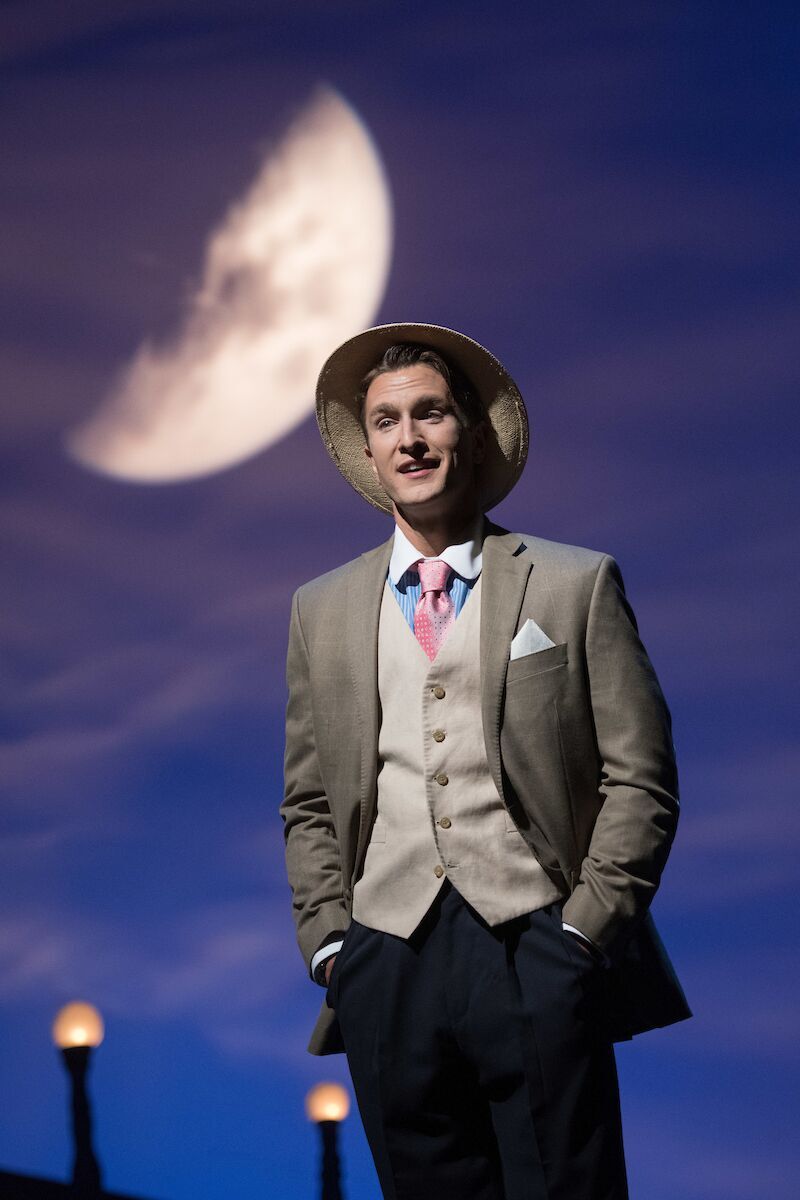

Sheet music cover for Cole Porter’s “Fifty Million Frenchmen,” 1929.

The rarest of the musicals was Cole Porter’s 1929 Fifty Million Frenchmen. Though New York has periodically seen resurrections of this delightful piece about Yanks on the loose in Paris – a 1991 version conducted by Evans Haile, a Lost Musicals import from England in 2006, and a Musicals Tonight version in 2001, among the best of them – this was the first fully staged production with full orchestra of my experience, and quite a delight.

Loaded with Porter pearls like “You Do Something To Me” (smoothly delivered by Stephen Faulk and Best) and “You’ve Got That Thing” (Nathan Brian and Joelle Lachance) the players were finely matched with their parts, and the action played out neatly on Daniel Hobbs’ pretty set. Versatile Hannah Kurth was showgirl May, and didn’t disappoint with her flashy numbers “Find Me a Primitive Man,” and “I’m Unlucky at Gambling.” And here was Devlin again outstanding in her songs, including “The Tale of the Oyster.” Yvonne Trobe – a standout in all her appearances this season – was amusing as the disapproving mother of Best’s character. Faulk, for whom this was something of a breakout season, had an especially sublime moment at the end of the first act singing the rueful “You Don’t Know Paree.”

Stephen Faulk in the 2018 production of Cole Porter’s “Fifty Million French Men” at Ohio Light Opera. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

In his symposium talk, Norton explained how the titular phrase had popular currency in that era, and played the song “Fifty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong,” written in 1927 and popularized by Sophie Tucker, to demonstrate his point.

Of more recent vintage, Richard Adler and Jerry Ross’ The Pajama Game from 1954 was also solid, anchored, as it was, by OLO’s stellar leading man Nathan Brian and Devlin who displayed fine chemistry. Brian did full justice to his character defining “A New Town is a Blue Town” and the show’s big hit tune, “Hey There,” and two of them sparked with “There Once Was a Man.” Sarah Best gamely essayed the role of Gladys originated by Carol Haney and danced a respectable “Steam Heat.” Neer excelled in the Eddie Foy, Jr. part of her perennially jealous boyfriend Hines. Reese was well cast as union agitator and would-be ladies man Prez, and Hannah Kurth aged convincingly as Mabel, partnering neatly with Neer on “I’ll Never Be Jealous Again.” These productions pride themselves in their completeness, and thus included the often forgotten “I”ll Never Be Jealous Again” ballet in the second act wherein Hines imagines Gladys’ multiple infidelities.

President Grant and Jim Fisk watch “La Périchole” at the Fifth Avenue Theater in New York, 1869. As shown in the “Illustrated Police Gazette.” (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

On the operetta side, Offenbach’s fizzy La Périchole probably ranked as the least effective of this season’s offerings. Though the score was beautifully played with requisite brio under the direction of Wilson Southerland, and the vocalists were all accomplished, the staging was merely efficient and felt more like “La Périchole-lite” with precious little Gallic (or Peruvian) flavor, and there was way too much slapstick for a work that doesn’t need it. (The new translation was by Jacob Allen.)

A scene from Julia Wright Costa’s production of “La Périchole” at Ohio Light Opera, 2018. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

Despite his boyish looks and manner, Neer’s casting as the heroine’s impetuous young boyfriend was a stretch, but like such other OLO stalwarts in the cast as Boyd Mackus as the Viceroy, sang more than creditably. And delightful company regular Gretchen Windt made a very appealing Périchole. Cory Clines had a funny non-singing bit as a bearded prisoner in the jail scene.

In his witty talk on the influence of Offenbach on modern culture, Senelick played us excerpts from classic French recordings of the score (with Suzy Delair and Fanely Revoil), and one could plainly hear what was missing in purely stylistic terms.

Kiah Kayser’s setting and Kim Griffin’s costumes were generically colorful, but didn’t much suggest Peru. “It could be anywhere,” remarked my elderly seat companion who fondly remembered the famous Met revival in the 1950s she had seen while still in college.

Senelick, incidentally, offered a second talk on the Moscow Art Theatre’s Musical Studio in the 1920s which gave the work in a revolutionary interpretation as one of its first productions. He also explained how Offenbach was once the most performed composer in the world. So much so that he related how in a Russian performance of Hamlet, there was an interpolated character of the Gravedigger’s Daughter who actually sang something from La Périchole!

Act I of the Moscow Art Theatre “Périchole” with Olga Baklanova in the title role and Yagodkin as Piquillo. (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

Altogether more satisfactory was Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe. In fact, it was one of the best productions of that work of my experience, nicely designed by Kim Powers (sets) and Jennifer Ammons (costumes). Imaginatively directed by OLO veteran Ted Christopher, who also played the Lord Chancellor with strong voice and incisive diction (his “Nightmare Song” tripped off the tongue effortlessly), and cleverly choreographed by Reese, the overture was accompanied by a balletic pantomime giving the backstory of the heroine Iolanthe’s thwarted alliance with the Lord Chancellor before she was banished “to live among the frogs.” There was only occasionally a sense of perhaps too much dancing. The first act finale with its confrontation of Peers and Fairies was especially thrilling.

Ted Christopher’s 2018 production of “Iolanthe” at Ohio Light Opera. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

Sarah Best made an ideal Iolanthe bringing great poignancy to the part, and dancing most gracefully too. Tenor Stephen Faulk successfully assumed the normally baritone part of Strephon. Brian and Benjamin Krumreig’s solos were beautifully sung, and the two excelled comically as those twittish lords Mountararat and Tolloller respectively, as did Hilary Koolhoven as shepherdess Phyllis. Clines made a stalwart Private Willis, while Julie Wright Costa was quite the best Queen of the Fairies I’ve seen, extracting the maximum humor from every line without overdoing it.

Surely the catnip for buffs this season was the rare production of Lehár’s 1924 Cloclo, not played in the U.S. until a 2009 mounting. Béla Jenbach’s libretto on this occasion (originally written for Leo Fall) was performed in Daigle’s expert translation. Infused with 20th century dance rhythms, it was written as the composer was half-way through writing Paganini. and at something of a career crossroads. The subsequent success of Paganini (and the fruitful start of his association with tenor Richard Tauber) led the composer to create more of those grandly romantic pieces with unhappy endings.

Cloclo, on the other hand, is more in the vein of a lighthearted farce, minus many of the elements of classic operetta, as Frey pointed out; there’s no nobility, no misalliance, no ball. I felt it might almost have served as the plot of one of those Jerome Kern Princess Theater shows.

Scene from Steven Daigle’s production of Léhar’s “Cloclo” at Ohio Light Opera, 2018. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

Cloclo is a Folies-Bergère performer with a platonic sugar daddy named Severin, who is the married mayor of Perpignan. When Cloclo sends him a letter asking for money, Severin’s wife opens the letter and assumes Cloclo is her husband’s illegitimate daughter (a revelation which tickles her maternal fancy), and invites the girl to come live with them, much to Severin’s surprise and consternation. She, for her part, loves the penniless Maxime (strong voiced Benjamin Dutton). Apple-cheeked Caitlin Ruddy made a spirited, well-sung heroine in a sort of American cheerleader way. Neer was amusing as her would-be older lover, going into paroxysms of discomfort any time she called him “daddy.” And Yvonne Trobe was touching and funny as the deluded wife.

So, too, there were some droll bits from Best as a daffy cook, Brian as a police officer assaulted by Cloclo, and Faulk as Cloclo’s amorous piano teacher.

Scene from Steven Daigle’s production of Léhar’s “Cloclo” at Ohio Light Opera, 2018. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

The show is really quite intimate in its scale, and the score pretty enough, especially a duet titled here “Love Will Pass Us By,” though on the whole, I felt, not perhaps rating as one of Lehár’s best, at least not on first live hearing. (There was a German radio performance a few years ago which struck me the same way.) But all praise to OLO for staging it.

At the symposium, the compelling Frey offered two interesting lectures related to Cloclo, one on the genesis of the work, and the other on the difficult lives of librettist Jenbach and Lehár’s other Jewish collaborators in the Nazi era.

Scene from Steven Daigle’s production of Bernstein’s “Candide,” Ohio Light Opera 2018. (Photo: Matt Dilyard)

Straddling the worlds of musical comedy and operetta is Leonard Bernstein’s troubled but glorious Candide. lt was given here in the excellent edition used by the Royal National Theatre in 1999 (which impressed me mightily at the time I saw it in London), and under Daigle’s brilliant direction, and Byess’ assured conducting, was far and away the best of the productions, representing an enormous leap forward for the company. Beautifully designed by Kiah Kayser (set) and Charlene Gross (costumes) – when the curtain rose, it might have been Le Nozze di Figaro – and cast to perfection, the performance elicited almost unanimous post show raves such as “it blew me away,” “tremendous,” and a chorus of “wow’s.”

Candide was double cast. At my performance, Krumreig was Candide, giving a gorgeously sung, movingly acted account of the role. Chelsea Miller was a tremendous Cunégonde, as virtuosic as any I’ve ever seen. Devlin deftly mixed humor and poignancy as the Old Lady. Caitlin Ruddy made an adorable Paquette. OLO veteran Boyd Mackus registered more strongly here as Martin than as the Viceroy in Périchole. So, too, Neer had his biggest and best parts as narrator Voltaire and Candide’s tutor Pangloss.

What made Candide especially thrilling was the morphing of these two-dimensional characters to ones we really care about by the end. And as misfortune follows misfortune, we come to genuinely feel for them. By the final curtain, there was not a dry eye in the house.

And though it may be a gratuitous observation, let me add that Bernstein’s score is absolutely sensational. OLO can be proud of having done great honor to the composer in his centennial year. The performance was prefaced by Symonds’ fascinating overview of Bernstein’s legacy with an emphasis on his New York themed musicals (On the Town, Wonderful Town, and West Side Story).

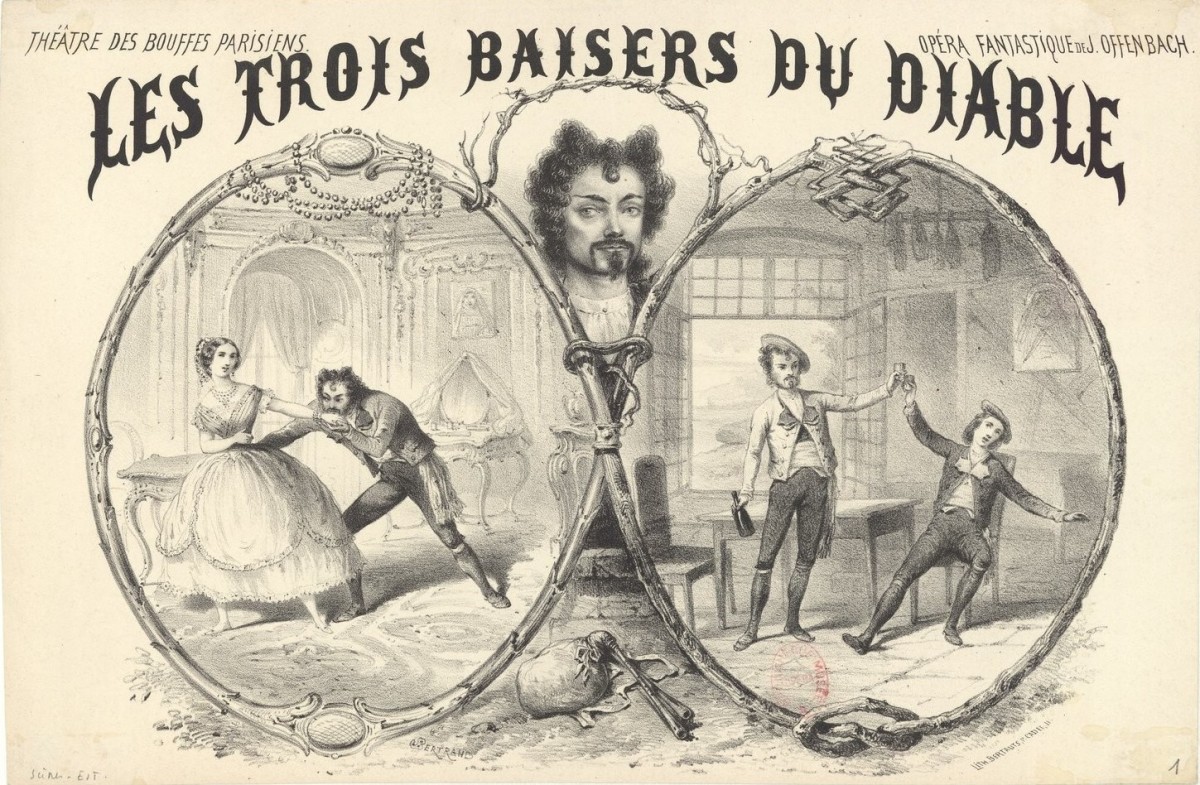

The mainstage productions were not the only music heard during the symposium week. There were, in addition, morning or (in one case) evening, concerts as well. Probably the most impressive of the lot was a musically complete concert version of Offenbach’s The Three Kisses of the Devil (Les Trois Baisers du Diable), with a libretto by Eugène Mestépès, which premiered in Paris in 1857. Performed in French with Southerland at the piano, it was a Faustian sort of tale involving a ne’er-do-well who has sold his soul to the Devil, and can retrieve it only if he gets the wife of his lumberback friend to kiss him three times. This was most definitely the composer not in an operetta mode, but rather demonstrating the operatic aspirations that would lead to his final work, The Tales of Hoffmann.

The Grand quadrille fantastique from Offenbach’s opéra fantastique “Les trois Baisers du Diable,” 1857 edition.

Ted Christopher sang very powerfully in his diabolic role. Ivana Martinic, who scored so impressively in last year’s symposium concert of “Ages Ago,” did so again as the wife, passionately resisting the man’s temptations as Marguerite does in “Faust.” Spencer Reese and Hannah Kurth also demonstrated their classical chops as the husband and neighbor respectively.

The other rarity – one of the three Victor Herbert scores unearthed after his death in 1935 (the other two being “The House That Jack Built” and “The Lavender Lady”) – “Seven Little Widows” was accorded an evening slot, but alas, featured merely excerpts introduced by Daigle who provided the interesting historical background. The work had book and lyrics by Rida Johnson Young (Naughty Marietta) and William Carey Duncan.

Once again, Southerland was the able accompanist opening the selection with the Interlude from the Prelude to Act 1, and this was followed by four vocal selections by Chelsea Miller and others, as well as another instrumental selection. What we heard was all very good, but it would have been more satisfying to hear the work in its entirety. Instead, the concert was rounded out with a fairly standard selection of Herbert “gems,” albeit well sung by members of the company. Audience favorites included Brian and Faulk’s campily over-the-top rendition of “The Streets of New York,” and Chelsea Miller’s “Art is Calling for Me.”

Traditionally, each year’s symposium contains a session of “Songs from the Cutting Room Floor.” This year, to commemorate the company’s 40th anniversary, this was expanded to two concerts, and included not only deleted songs from the current shows, but songs cut from past OLO productions, including Fiddler on the Roof, The New Moon, The Violet of Montmartre (who knew that Johnny Mercer wrote lyrics to a Kálmán work?), The Arcadians, and White Horse Inn.

Jonathan Heller’s jaunty “When I Go Out Walkin’ with My Baby” intended for Oklahoma!; Benjamin Dutton’s “I’m Just a Sentimental Fool” and “Neath a New Moon” (the latter with Best); and Devlin’s “Vive La You,” written by Rudolf Friml for the 1950s film of The Vagabond King, were among numerous highlights. The first act closer, “Let’s Make It a Night” excised from Porter’s Silk Stockings with its infectious repetition of “Let’s,” became an instant earworm.

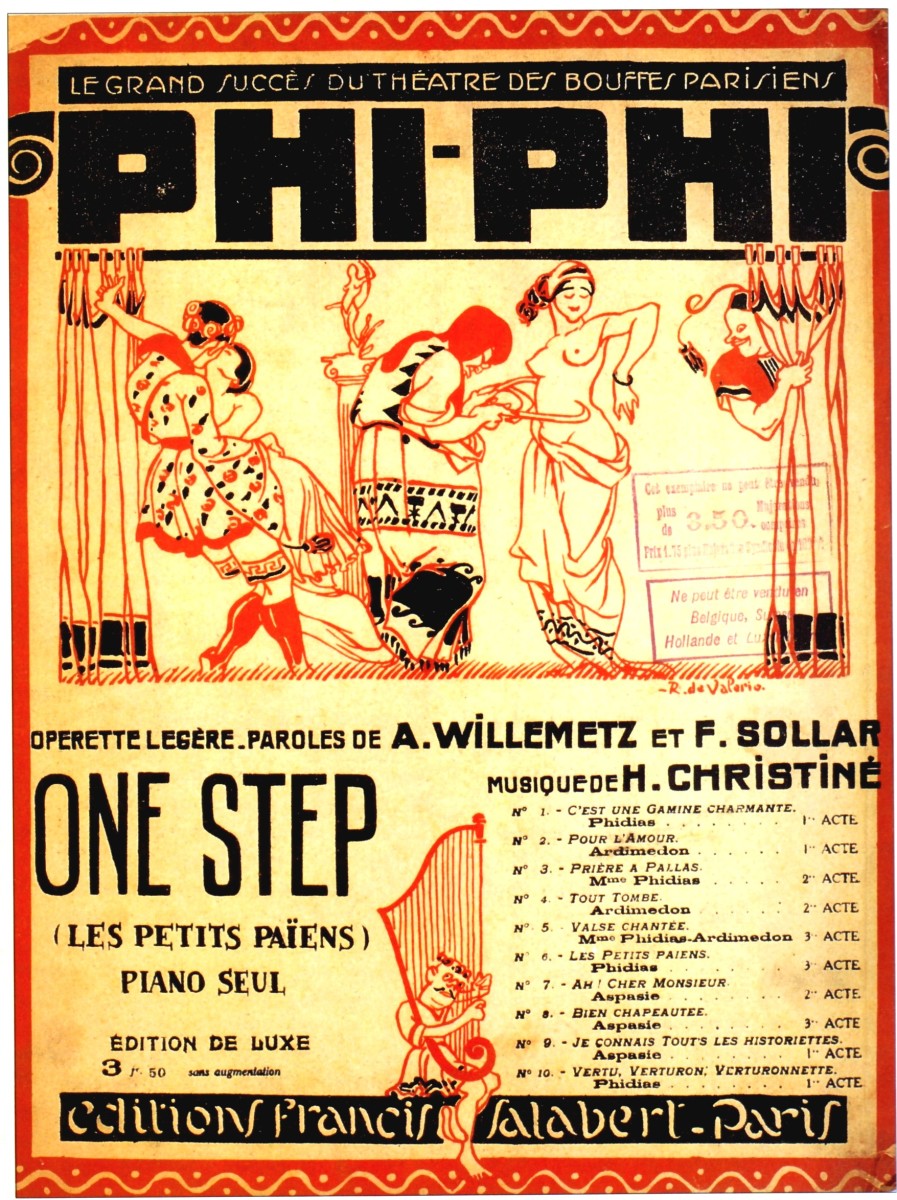

Sheet music cover for “Phi-Phi”.

Complementing this two-part concert, there was another double header labelled “The Next Forty Years,” divided into operettas and musicals, and offering selections from shows that OLO has never done. Phi-Phi, Venus in Silk, Rio Rita, The Pink Lady, Watch Your Step, Anya, and Christine were among the tantalizing selections which may or may not ever see the light of day in Wooster.

All these concerts offered the chance for members of the ensemble to join principals in the spotlight, once again affirming the excellence of the company. Mailee Herzog’s “Love Will Find a Way” from The Maid of the Mountains, Sadie Spivey and Trevor Todd’s “Perfectly Marvelous” from Cabaret, Garrett Medlock’s “She Loves Me,” and Adam Kirk and Emily McCormick’s “They Like It As Much as the Men” from Jean Gilbert’s The Joy-Ride Lady were just a few of the standouts.

Conducting chores were taken (in polished fashion) by J. Lynn Thompson (The Pajama Game, Iolanthe, Fifty Million Frenchmen), Steven Byess (Babes in Arms, Candide, Cloclo), and Wilson Southerland (La Périchole, Iolanthe).

Direction was handled by the mighty Steven Daigle (Babes in Arms, Fifty Million Frenchmen, Candide, Cloclo), Ted Christopher (Iolanthe), Julia Wright Costa (La Périchole), and Jacob Allen (The Pajama Game).

The London version of Abraham’s “Ball at the Savoy” with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, showing Rosy Barsony on the cover.

Though we had already sampled some of Daigle’s possibilities for the future in the aforementioned concert, he asked the guest speakers at the closing roundtable which shows they would like to see performed there or anywhere. Senelick, quite logically, wished for more Offenbach or one of the other major composers of French operette like Hervé or Hahn. Norton expressed a desire for Paul Abraham’s Ball im Savoy which Oscar Hammerstein II adapted for its London production.

Symonds opted for one of the Ivor Novello shows, particularly Gay’s the Word, and one of Kurt Weill’s shows such as Lady in the Dark or Down in the Valley.

Historic postcard advertising “The Girls of Gottenberg” with music by Ivan Caryll and Lionel Monckton.

And Frey, for his part, suggested Caryll and Monckton’s The Girls of Gottenberg, the Kálmán Broadway titles such as Miss Springtime (Die Faschingsfee with Jerome Kern interpolations) or his unproduced collaboration with Lorenz Hart (Miss Underground). He also voiced a strong preference for the 1907 Adrian Ross version of The Merry Widow which he feels beats the original.

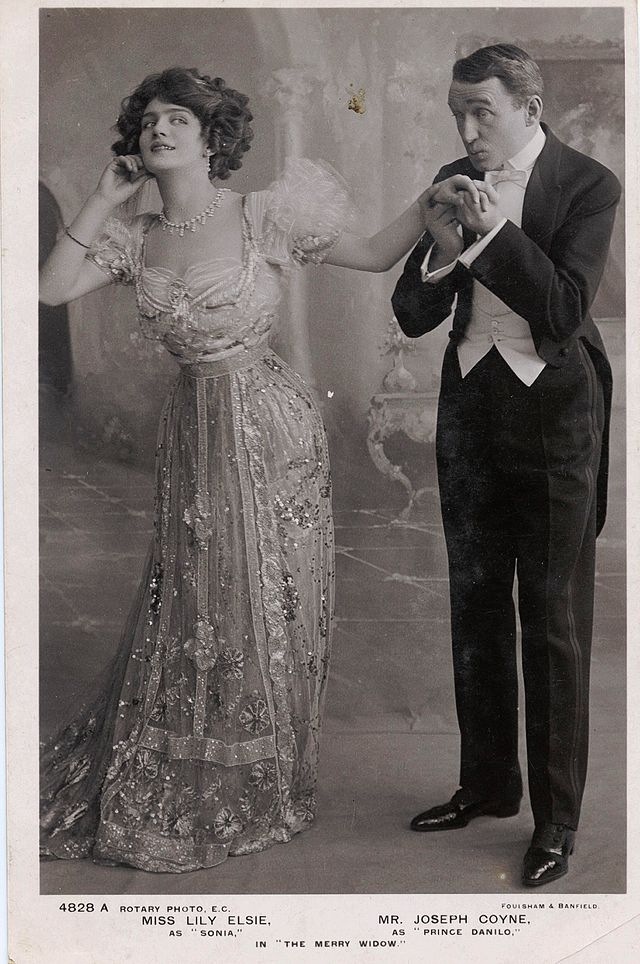

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in “The Merry Widow.” In its English adaptation by Basil Hood, with lyrics by Adrian Ross, the show became a sensation at Daly’s Theatre in London, opening on 8 June 1907.

It doesn’t seem OLO will run out of rich material anytime soon. I look forward eagerly to whatever goodies next season may bring.

For more information of Ohio Light Opera, click here. The original version of Harry Forbes’s article can be found here.