Michael Hardern

Operetta Research Center

15 February, 2019

Ah yes, the Weimar Republic. Again? While the Museum für Fotografie in Berlin is currently showing a marvelous exhibition on the revolution of 1918/19 that lead to the founding of the first German Republic, combining revolution and street fighting photos with ‘entertainment’ as a counter mirror of social upheaval, and adding a symposium on March 1 to discuss what cabaret, film and operetta have to do with politics (with guest speakers such as Alan Lareau and Kevin Clarke, as well as curator Evelin Förster), there is something else to look forward to. On 19 February the Philharmonie in Berlin will host a talk in their ‘Philharmonischer Diskurs’ series entitled ‘Babylon Berlin.’

The cover of the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.” (Verlag Kettler)

The guests for the Philharmonic talk are bestseller-author Florian Illies, historian Manfred Görtemaker, and journalist Tilman Krause as master of ceremonies. They want to discuss how ‘golden’ the Golden Twenties actually were.

From an operetta perspective, it might be said that the Weimar Republic years of operetta ‘Made in Berlin’ were nothing short of miraculous. The sheer number of hits that premiered during those years is staggering, as is the musical innovation these shows demonstrate.

Poster for Charell’s revue “Von Mund zu Mund”.

It starts with Eduard Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda in 1920 and his intoxicating ‘Batavia Foxtrott,’ continues via the dazzling revues and revue operettas by Erik Charell, culminating in Casanova, Drei Musketiere, and Im weißen Rössl.

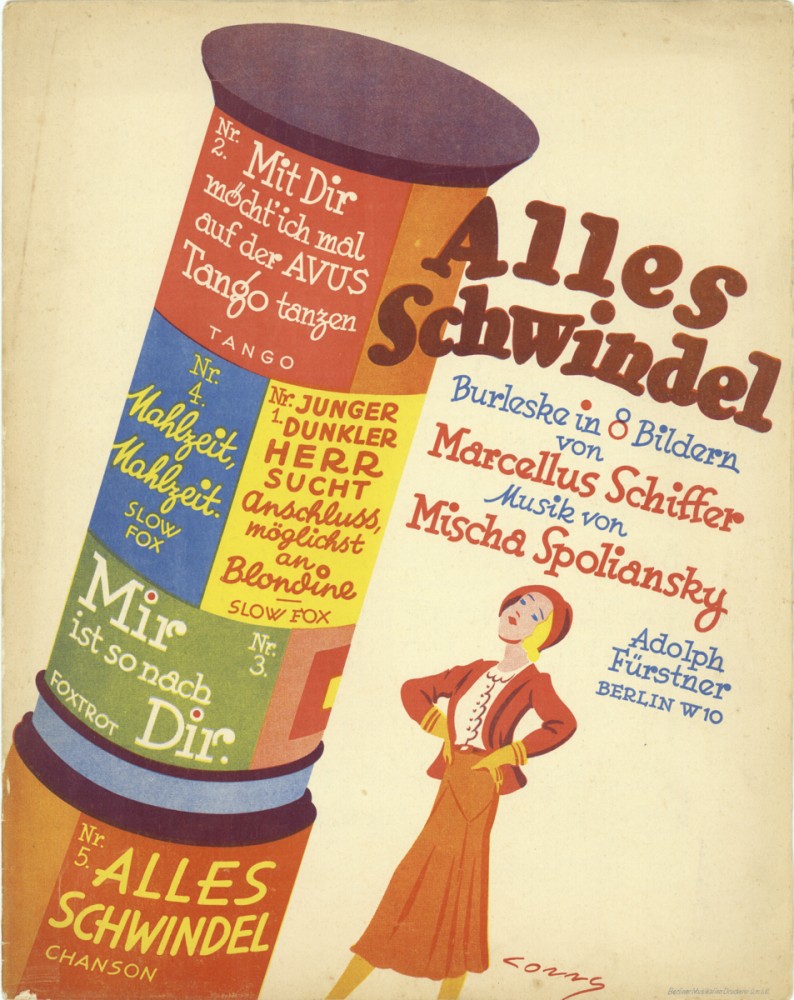

Then there are the ‘romantic’ Lehár operettas written or adapted for Richard Tauber and premiered in Berlin: Paganini, Friederike, Das Land des Lächelns. There are also the new Tonfilmoperetten by Werner Richard Heymann, and the cheeky cabaret operettas of Mischa Spoliansky, e.g. Alles Schwindel, Rufen Sie Herrn Plim and Zwei Krawatten.

The original 1931 poster for “Alles Schindel.”

And let’s not forgot the Berlin triumphs of Fritzi Massary with Leo Fall titles such as Madame Pompadour and Oscar Straus works like Die Perlen der Cleopatra.

There are, of course, the glorious heights of Paul Abraham too, whose Viktoria und ihr Husar, Blume von Hawaii, and Ball im Savoy all started their meteroric careers in Berlin.

Sheet music cover for Paul Abraham’s “Die Blume von Hawaii,” 1930. (Photo: Archive of the Operetta Research Center)

Whether Mr. Krause and his talk guests will discuss the musical entertainment side of ‘Babylon Berlin’ remains to be seen.

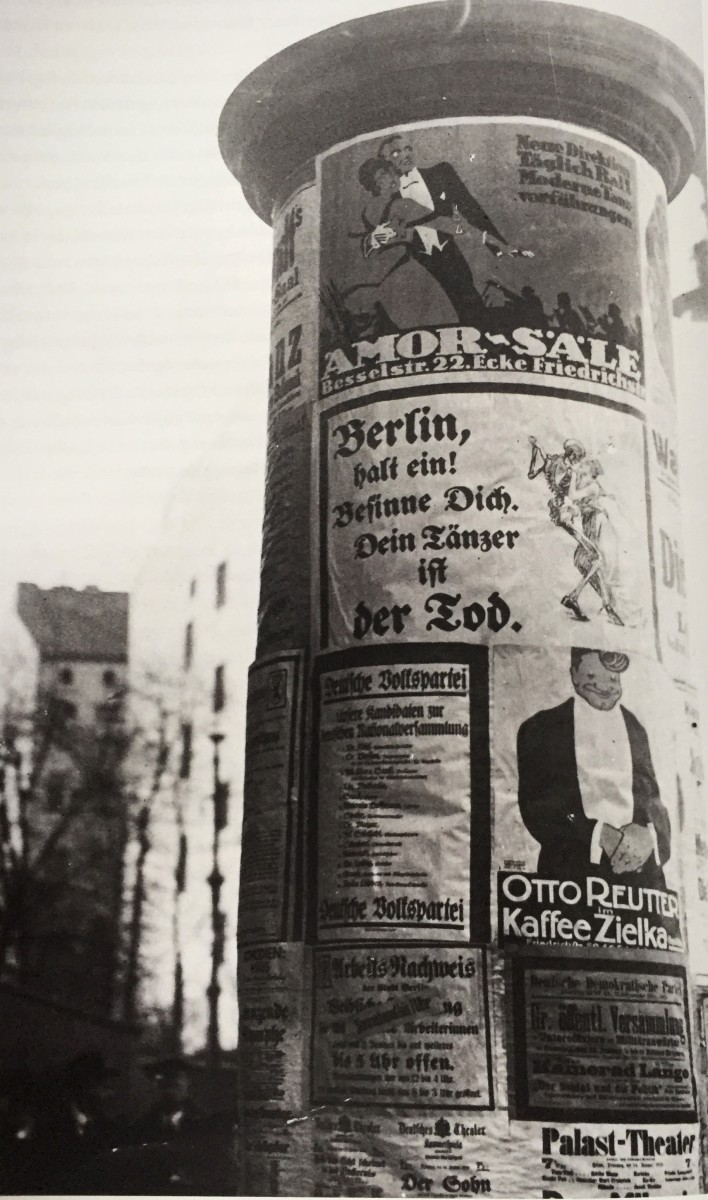

Derek Scally in the Irish Times wrote a big article about this recently in his ‘Letter from Berlin.’ He stated: ‘For a city so rich in culture, and drowning in history, it is surprising to experience first-hand Berlin’s long cultural history drought. The ruptures of war, and the postwar suspicion of anything homegrown, has seen Weimar-era musical theatre, for instance, pared back to threadbare Threepenny Operas and a careworn Cabaret revival that has been playing to tourists for a decade. But Berlin’s growing international cachet in the last decade appears to be having a positive, knock-on effect on locals, encouraging them to explore their own cultural past with greater curiosity than before.’

Advertisements in Berlin in January 1919, combining political messages with show business. (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

The ‘exploring’ involves many revivals of long forgotten works by Straus, Abraham and Spoliansky. It also involves institutions such as the Museum für Fotografie including operetta and the entertainment industry in their discussion of important historical changes such as the 1918/19 revolution.

Advertisment for “Berlin Babylon”, which is also shown on Netflix.

It means that the TV series Babylon Berlin – which lends its name to the philharmonic discourse evening – included much music from the above mentioned operettas, e.g. the song “Mir ist so nach dir” from Alles Schwindel. It had barely made a comeback in the Maxim Gorki Theater production that it popped up in season 2 of the series.

Sung in the TV series by Volker Bruch and Hannah Herzsprung, the two actors carry the fame of that number out into the world, in a way a book like Marcellus Schiffer: Heute nacht oder nie (by Victor Rotthaler) never could. (Mr. Schiffer wrote the lyrics for Alles Schwindel.) And in a way that Jonas Dassler and Vidina Popov on stage could never do either.

Jonas Dassler and Vidina Popov as Tonio and Evelyne in “Alles Schwindel” at Gorki Theater, Berlin. (Photo: Ute Langkafel)

According to the Irish Times, Berlin is currently rediscovering ‘operetta’s true diversity, highlighting pan-sexual extravaganzas that go far beyond the perfumed operetta cliche.’ And that’s what Babylon Berlin is doing on a grander scale as well.

Even a work such as Frühlingsstürme by Jaromír Weinberger is scheduled for a comeback in Berlin, at the Komische Oper. Labeled by some as ‘The Last Operetta of the Weimar Republic’ because it premiered in 1933 with Richard Tauber in the lead role, it certainly marks the end of an era.

But what happened after 1933 is also of new interest. The Komische Oper presented Nico Dostal’s Clivia some years ago, a show that premiered in December 1933 and mirrored many of the new ideological ideals.

Coming up in May 2019 in Abraham’s Roxy und ihr Wunderteam which originally premiered in Budapest and Vienna in 1937, before the ‘Anschluss.’ It shows how exiled authors such as Abraham and Grünwald poked fun at Nazi ideology by turning it upside down. Adding ‘degenerate’ music to a very ‘Aryan’ plot that starts out ‘heroically,’ before the action turns totally amok.

The original Viennese “Roxy” team: Oscar Denes (l.), Rosy Barsony, and Hans Holt. (Photo: ORCA)

In a way, that is the real ‘Last Weimar Republic Operetta.’ The movie version came out in early 1938 and never went into wider circulation because the Nazis invaded Austria where is immediately disappeared from cinemas.

Roxy also highlights a very specific German humor that in this case is more Austro-Hungarian but still typical of many Weimar Republic products. After all, Abraham’s other famous lyricist was Fritz Löhner-Beda who wrote so many of the era’s nonsense ‘Schlager’ that we still enjoy today.

He also wrote the Buchenwald Lied while in the concentration camp of the same name, before he died in Auschwitz in 1942.

Bringing these various levels of discourse together – the tragedy, the humor, the liberation, the jazzy glamour, the human despair – is what makes the discussion of Weimar Republic operetta so fascinating and worthwhile.

Here, you can see and hear Friedrich Hollaender singing ‘Ausgerechnet Bananen’ with a text by Fritz Löhner-Beda in the 1961 movie Eins, Zwei, Drei by Billy Wilder (who of course knew Mr. Löhner-Beda and about his fate).

It will be interesting to see where the new discussion shall lead us – hopefully further than it did back in 1961 when noone wanted to hear about the fates of Löhner-Beda and all the other. And when noone was seriously interested in jazz operettas as ‘revolutionary’ pieces from the German past!

For more information and tickets for the ‘Philharminischer Diskurs’ on February 19, click here. For details on the symposium at Museum für Fotografie, click here.