Chris Weber

Operetta Research Center

11 October, 2023

We’ve all read stories about the big players: Jacques Offenbach, Ludovic Halevy, Henri Meilhac, and certainly Napoleon III. But you can get a better—and certainly more interesting picture – with the ‘little’ stories, the tales of those people who come into intimates contact with those great names. Even better if their stories tell you about the world in which they all lived.

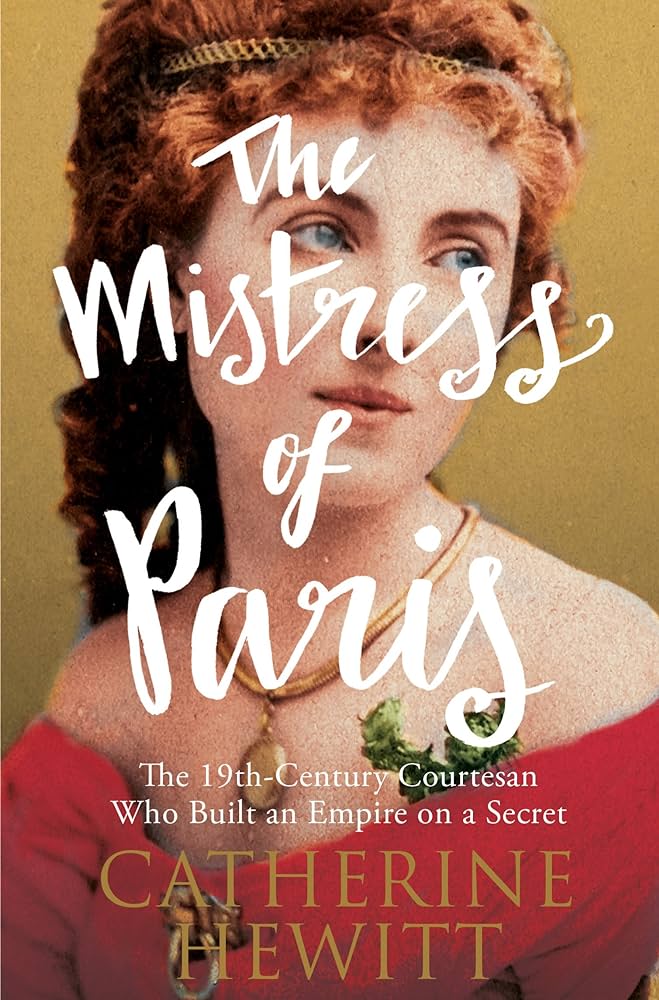

Catherine Hewitt’s “The Mistress of Paris”. (Photo: Icon Books)

After all, Offenbach did not live in a vacuum. Whom did he live with? Or to put it bluntly, whom did he sleep with? While this doesn’t tell you what made him “tick”, you are naturally interested in anyone who he was interested in.

I became interested in Valtesse de la Bigne (1848-1910) when I read the liner notes of Opera Rara’s wonderful new recording of La Princesse de Trebizonde. Jean-Christophe Keck tells of the long-suffering Mrs Offenbach coming with the local police to eject Valtesse from the first night audience at the original premier of La Princesse de Trebizonde in Baden-Baden. If you don’t have the CD, please get it: it’s wonderful. But if you don’t, you can read what I wrote about it here.

The thing is that there seems to be a discrepancy: there are two versions of that story. The book I’m reviewing here (and it’s about time I told you the title of it) is called The Mistress of Paris. The subtitle “The 19th-Century Courtesan Who Built an Empire on a Secret” may not really be needed. But it was probably put on to tease people into buying it. You don’t need to be teased. This is a wonderful book by Catherine Hewitt, and it was the first of a series of books on undeservedly little-known 19th century French women.

If you want a short, 15 minute, biography of her, go here:

Another one, twice as long, but I’m not sure twice as good, is here:

The “secret” Hewitt refers to in her subtitle was that nearly everything about Valtesse was invented. Life dealt her a rough hand at birth. Child of a violent, alcoholic father and a ‘sex-worker’ mother, she was raped in the street at age 13, became a prostitute, and there, like all too many women of that time – and ours – her story might have ended. But there was something about her: she longed to educate herself; to become something better. So, step by step, that’s what she did. It helped that she had dazzlingly red hair, porcelain white skin and was strikingly attractive.

Valtesse de La Bigne in a portrait by Henri Gervex. (Photo: Musée d’Orsay)

It was Jacques Offenbach who was instrumental in Valtesse’s journey to the top. But also, it was the times: the Paris of that era was a place where almost anything could happen. The world that gave us those wonderful romances by Alexandre Dumas like the Count of Monte Cristo (a story where marvelous things do happen with perfect believability) could give us a Valtesse. She came up with the name because it was so close to “Votre Altesse”, or “Your Highness”.

She later added de la Binge as it was an aristocratic version of her mother’s last name, Delabigne. Fortuitously, it was also a famous old name from the Normandy Calvados region she originally came from.

In today’s world where you get a Social Security number from birth and cameras follow you everywhere, it probably isn’t possible to do what she did. The pre-1914 world was more gracious, and more free, in that regard.

Self-Educated with Eyes and Ears Wide Open

And yet the eternal verities held true then as now. If you want to get ahead in life, spend less than you earn and educate yourself. Keep your eyes and ears open and your mouth shut, and attach yourself to only the best in both things and people. This Valtesse did, consistently. I’m not going to call her by her birth name: I’ve actually forgotten it. She made herself from top to bottom. Of course, she had an innate sense of style without which she likely couldn’t have gone far.

You learn about the different levels of prostitution in the book: at the lowest rank were the streetwalkers, called grisettes. Up from that were lorettes, the more respectable mistresses. Top of the heap, and devilishly hard to get into were the upper-class courtesans.

Valtesse never seems to have been a grisette: there is no talk of the pimps or procurer that either protect or exploit her. From a very early age, Valtesse was different. This is nowhere more clearly seen than with her relationship with the famous painter Camille Corot.

The painter Camille Corot. (Photo: Nadar)

He was much older than her; there never seems to be any hint of anything but an artist/model relationship. Except that there was more than that: she learned all she could from him, asking questions about perspective, color, and any other important aspect of what makes a great painter, or separates him from the mediocre.

Corot lived in her neighborhood, and from a young age Valtesse had a very arresting look: bright red hair which when the sun hit it just right had steaks of gold. And blue eyes that bewitched so many. A nose, a figure … she had it all except for breasts that she lamented were too small. Nowadays she could do something about that, but it doesn’t seem to have hurt her.

She quickly moved on to rich clients: that was where the money and security was. But the unexpected happened: she fell in love, a real, deep and true love. It was with a young man from a wealthy family who loved her, and gave her two daughters, yet though he repeatedly promised, would never marry her: his family wouldn’t hear of it. And they threatened to cut off his allowance if he did marry, against their will.

Valtesse de La Bigne, portrait by Édouard Manet, 1879. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

So there she was—a teenager with two children and only one profession to fall back on. It could have turned ugly from here, but it didn’t. The reason seems to be Jacques Offenbach. Giving her babies to her mother, Valtesse changed her name and resolved never to be dependent on any man.

It was her neck-turning looks and manner of holding herself that brought her to Offenbach’s attention. Unlike stars like Hortense Schneider, Valtesse had no talent besides those looks. She first appeared on stage in a revival of Orphée aux enfers in the 1860s. She was Hebe, the goddess of youth, appearing with the other deities on Mount Olympus in Act One, Scene Two in a non-speaking role. She was 15. Her looks got her noticed by newspapers; one critic described her as “as red and timid as a virgin by Titian”. Even then, she could appear as something other than the fact.

Her First Speaking Role

Soon afterward she had her first speaking role in the one-act Le fifre enchanté, done at Bad Ems in July of 1864. It premiered one day after her 16th birthday. (It first brought her in contact with the team who would write the words to Trebizonde four years later.)

Then came another one-act revival at Bad Ems: La chanson de Fortunio as Saturnin, a clerk (so a “pants role”). The next role appears to not be until the fateful year of 1869, when on March 22 La Diva premiered. A three-acter by the famous team of Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, who both figure in Valtesse’s life. She played “Berthe”, but sadly this means little to us today: we do know that famed mezzo Frederica von Stade once expressed deep interest in reviving La Diva, but that never happened.

It’s never been recorded, and these few YouTube snippets are about all that exists. Here is the overture:

The next work, a few weeks later, was the now-famous La Princesse de Trebizonde. Valtesse had a small role as a page. Now, if she was appearing in the first version, at Baden-Baden in July of 1869, then it is hard to imagine her being in the audience and Offenbach’s wife Hermine getting the local police to eject her!

We know that the Offenbachs had a very secure relationship. His family was important to him. Yes, he had dalliances with the actresses and others who threw themselves at him. But even though he had two illegitimate children with courtesan and singer Zulma Bouffar, his wife was not threatened. Bouffar created many famous Offenbach roles, e.g. Gabrielle in La Vie Parisienne, Fragoletto in Les Brigands, and Prince Caprice in Le Voyage dans la lune (click here for more information).

Zulma Bouffar photographed by André Disdéri in 1866.

Another love was French comic actress Anna Judic. Judic was no courtesan, but a bonafide singing actress of great renown. For Offenbach she sang the lead in Le Roi Carotte (of which more later), Madame l’Archiduc, La Creole, Bagatelle, Grand Duchesse de Gerolstein, and La belle Hélèn. She also sang leads in works of Hervé (an operetta writer we should be more familiar with).

On top of that, an affair with Cora Pearl is rumored about, Pearl – as one of the most famous grandes horizonzontales of Paris – sang Cupid in the revival of Orphée in the late 1860s that also saw Valtesse as in a minor role, while Valtesse had no words to say, Pearl had no clothes to wear as Cupid. It caused a sensation – and top ticket prices!

Famed courtesan Cora Pearl as Cupid in the “Orphée” revival, Paris 1867.

Yet Hermine never seemed to be threatened by Bouffar, Pearl, Judic, or any of the others as she was by Valtesse. According to Hewitt’s book, things came to a head in February of 1870, when Offenbach took Valtesse to her first and perhaps only visit outside of France, to Italy. Hermine tracked them down in a Turino hotel (with the help of the local police) and confronted them.

Playing Mistress Johnson with an American Accent

Valtesse was nothing if not smart: she got out quickly and cleanly. Her timing was excellent: in a few months, the Franco-Prussian War would begin, and Offenbach would be persona non grata in an unforgiving, humiliated and angry France. If she was with Offenbach (he was 50, she was 21) to boost her career, he would not be in any position to further help her: Her last and largest role was a singing one in La romance de la rose.

This one-acter, which premiered (astoundingly) one day after the premiere of Les Brigands (with Bouffar) one of the most beloved of all his works. If that weren’t enough, the revised version of La Princesse de Trebizonde (the one we know today) premiered a mere three days before Les Brigands.

La romance de la rose has never been recorded. Her role was an American widow called Mistress Johnson who is seduced by a beautiful voice she hears singing one day. She mistakenly attributes this voice to the wrong person – and amorous chaos follows. (Including the jealous partner of the character who Mistress Johnson thinks is the owner of the beautiful voice.) Valtesse’s American accent apparently needed much work. She gets to say these lines:

Oh very good!

Oh very well!

Joli, charmant, spirituel!

Oh, sire, c’était très bien, très chic!

Oh! What is sweet love in miousic [sic]!

Here is the overture conducted by the late, great Offenbach specialist Antonio d’Almeida:

La romance de la rose premiered on December 11, 1869. It would be the last Offenbach premiere for two years. And these were two of the worst years in Parisian history. If you know the story of the Prussian siege, the bloody Commune, and how the French had to eat rats, and the 20,000 who died in the streets, and the destruction of the Tuileries, well, it is not a pretty tale.

Offenbach fled Paris early, somehow sensing what would happen. He lived in Spain, Vienna and London. The first new music he’d write wouldn’t premier until January, 1872. The title Le roi Carotte came from a tale by E T A Hoffmann. “The King’s Bride” with a translation by Paul Turner is a magnificent version. It’s a small book, with just the one tale, but if every Hoffmann tale was so well translated, this world would be wonderful. I can’t recommend it enough.

The English edition of “The King’s Bride” by Paul Turner. (Photo: Alma Books)

I mention it at all because the story of the Carrot King and his wish for a human bride is all very fantastical, and far away from his edgy satires of the 1860s. Paris had changed, and wanted fantasy.

In the meantime, Valtesse had fled to Nice: her ties to Offenbach would never again be so tight. Still, both she and Anna Judic attended Offenbach’s funeral. I wonder what that would have looked like, with Hermine and the children also there.

“The Thinnest Man in Paris”

But before we leave Offenbach, we’ve collected the stories of him that come out of this book. Called “the thinnest man in Paris”, his grandson swore that O. never weighed more than 50 kilos. That’s 110 lbs, and hard to believe. And yet you see it in his photographs. He was always moving, hating solitude. One comment was that he had “demonic energy” reminiscent of Paganini.

The young Jacques Offenbach playing the cello. A caricature from the 1840s.

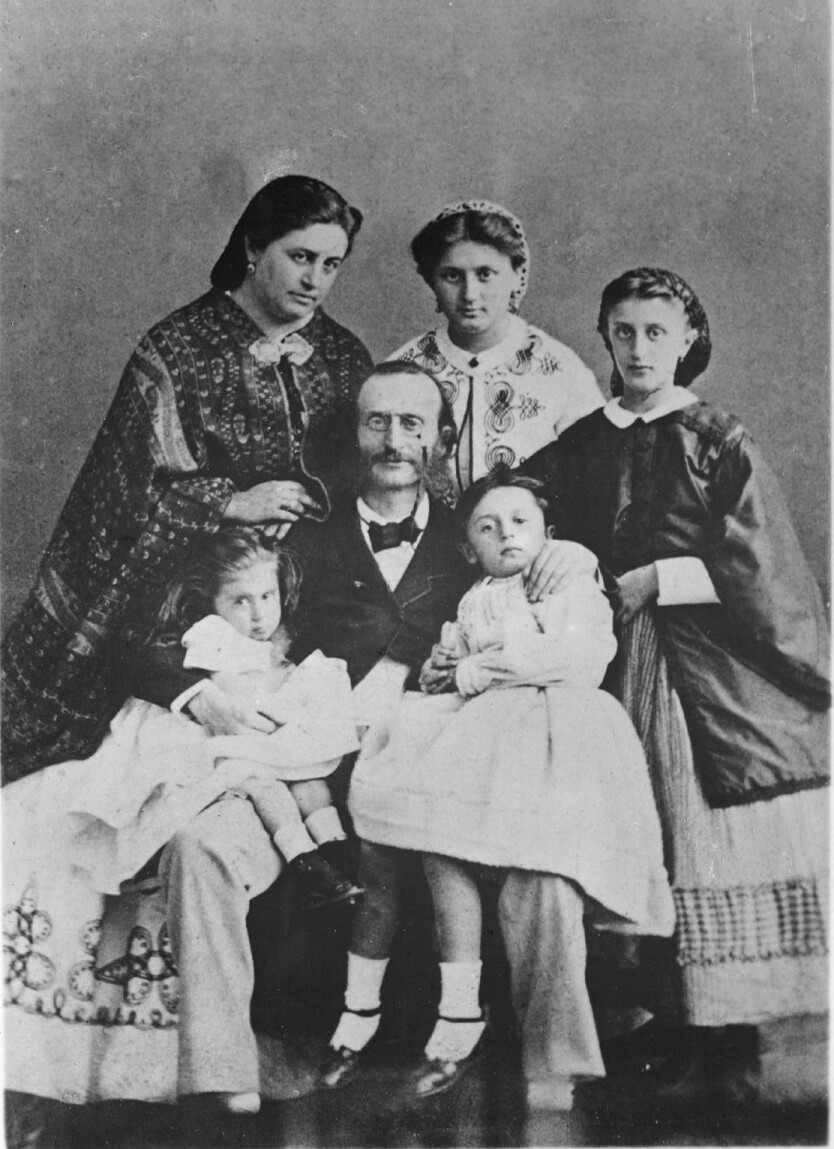

The Valtesse biography makes it very clear that the Offenbachs had a solid marriage. In the summer of 1869, just after the Trebizonde triumph, they hosted a gala party in honor of their 25th wedding anniversary at their summer home at Étretat, then as now a lovely destination.

Jacques Offenbach surrounded by his wife and children. (Photo: Kölner Offenbach-Gesellschaft)

Offenbach was always discreet in his affairs. Hermine’s only rule seems to have been: “Don’t humiliate me in public”. However, somehow Hermine had an inkling about Valtesse that she never had with the others. It is also true that Valtesse was the only ‘actress’ on his stage who really had no talent for singing. Again, it must have been her looks that captivated the mostly male audiences.

Offenbach was a huge help to Valtesse. He taught her how to behave and live in high society; lessons which were priceless and greatly appreciated.

Still rough around the edges when she first met Offenbach at 15, when they parted at 21 she was ready to conduct herself flawlessly in the highest of society. (The affair seems to have begun when she was 20, but it is impossible to say for certain, and it really doesn’t matter.)

A final work, Mam’zelle Moucheron was planned for her, but much interfered: the spousal intervention, the war, and in any case it finally appeared as a one act work that premiered in May of 1881, over eight months after Offenbach’s death.

“Bad Blood”

Valtesse always acknowledged how important Offenbach had been to her. After the polish she received from him, she was ready to mix anywhere. As an aside, she relates that he never had strong political views. She was a Bonapartist and strong adherent to the Second Empire. But he seems to have had bigger fish to fry.

The 1870s and 80s were a real mishmash for French politics. A republic had been declared, but France had mostly known monarchy, and there were strong monarchical feelings. But which monarch? There were three different competitors. Had they all agreed on one France could still be like Britain today, a constitutional monarch. But the three families could never unite: they were all too different. Even today there are three different “pretenders” to the French throne.

You have the traditional Bourbons, the family of Louis XIV, XV, XVI and XVIII. This immediate branch was overthrown in the Revolution of 1830. The one who became king at that date was from the Orleans branch of the family. They were cousins of the Bourbons, who have never forgiven them for supporting the Revolution and even voting for the death of King Louis XVI. This branch produced “the Citizen King” Louis Phillipe, who reigned from 1830 (the last of the Bourbons) to 1852 (Louis Napoleon, who became Napoleon III). So today you have representatives of all three families. Both Bourbon and Orleans regard the Bonapartes as arrivistes .

Almost certainly, they will never unite behind one would-be monarch.

So however high the French view the British royal family, there probably will never be another French one. Too much ‘bad blood’ has been spilled, often literally.

The bed designed by Édouard Lièvre, currently exhibited in the Valtesse de La Bigne room at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. (Photo: THOR / CC BY 2.0 Deed)

Valtesse had varied interests, all of them deeply researched. She saw an opportunity for France in Indochina and was a power behind sending an army to Hanoi in 1873. That’s a fascinating story in itself. Knowing that a woman of her background could not go public with her views, she cultivated politician Leon Gambetta. The rest is history, and ended in 1953, when the French were finally defeated and the Americans came slowly but surely to take their place before they, too, were defeated in Vietnam.

Mysterious Beauty

As Valtesse aged, she began to cultivate a group of proteges. None were closer to her than a young woman named Liane de Pougy. Though Liane was to be very different, she was Valtesse’s successor in absolute and mysterious beauty. The story is told that Offenbach’s librettist Henri Meilhac once paid Liane 80,000 francs simply to gaze on Liane’s naked body. (Being increasingly “portly” as he aged, this may well have been all he could do anyway.) He was fabulously successful, and a bachelor all his life.

Liane de Pougy in 1891. (Photo: Reutlinger)

Still, do you have any conception of how much 80,000 francs was in today’s money? While there are several ways to convert past money into present value, I prefer the time-tested method of gold, and what it can buy. All through the 19th century, until 1914, the gold franc, or rather 20-franc coin, was the common currency. Through all of the changes of regime, from First Empire, to Restoration, to Orlean, to Second Empire, to Republics, the faces on the 20-franc gold coin changed, but the weight never did. Each 20-franc coin contained 0.1867 troy ounces. (Somehow fitting here as 1867 was the year of many of the triumphs of Offenbach, Halevy and Meilhac.)

In any case, it took 4,000 of these 20-franc coins to equal 80,000 francs of a France still on the gold coin standard. And 4,000 times 0.1867 oz equals 746.8 ounces of gold. At current prices around $1900 per ounce this comes to $1,418,920 in US dollars. So over $1.4 million just to gaze at Liane’s naked body! He was quoted, “The greatest beauty ceases to exist besides you.”

Liane’s rather androgynous look appealed to the chic of the 1890s. Born in July, 1869 (at the day of Trebizonde’s first premier) she was just 27 when Meilhac died at age 66. So he must have been near death when he paid that much, and as a bachelor, may not have had any heirs to leave it to.

Liane de Pougy in 1900. (Photo: Author unknown)

But Liane created problems for Valtesse: she was Liane’s closest friend by far, and certain rumors did her no good: The younger woman increasingly came to only want to be with other women. In Valtesse’s world, while occasional dalliances were one thing, a serious and public lesbian affair could cost Liane her career. And exactly such a public affair threatened all that Valtesse had planned.

An affair with another courtesan named Emilienne d’Alencon became the subject of mockery in some Parisian journals. There were humorous announcements of the couples’ forthcoming wedding date and even the imminent arrival of a child!

Émilienne d’Alençon in 1902. (Photo: Author unknown)

Valtesse pulled out all stops to end this: Had Liane not noticed how quickly lesbians aged? At 20 their wrinkles were already beginning to show!

But then Liane’s affair with American socialite Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972) became the subject of Liane’s novel Sapphic Idyll in 1901. It went through 40 printings the first year.

Natalie Clifford Barney. (Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Somehow, with the know-how that Valtesse continuously exhibited throughout her life, the scandal missed hitting her. And finally, all came out a happy ending when Liane announced her engagement with a Romanian prince. Finally, a girl of the streets ending up a Princess, her past washed clean.

You’ll have to read this extraordinary book to see how well Valtesse managed her money and ended up independently wealthy. She never forgot those who helped her on the way up. And she never seems to have hurt anyone. With all her calculations, she always retained a true heart of gold.

Above all, she showed over the course of her life’s many inventions that the most implausible fiction can be believed if it contained even a grain of truth.

This is a book that, once read, remains in your memory.

Hi Chris,

a highly interesting review and a book I would like toread, and Valtesse would have been historically memorable just for the list of major painters in whose works she appeared.

However just one error, Liane de Pougy was never a girl of the streets, she was an even more remarkable and unusual phenomenon: a young bourgeois girl, who realised how limited were the lives of women of her class and managed to escape into a far more glamorous and expansive world

Thanks so much for your comment, Juliette. I wonder if the author, Catherine Hewitt will read this exchange, as she implies what I wrote. May I ask regarding yours, what are your sources?

Maybe I got the story wrong from the book: I must go back and re-read it. Catherine saw my review before it was published and was silent on this part.

Best,

Chris