Christopher Weber

Jacques Offenbach Society Newsletter #105

1 September, 2023

Ever since that night so many years ago when I saw my first Offenbach (November 4, 1974, Hoffmanns Erzählungen, at the Vienna Volksoper), whenever I ran into anyone else who liked him, I had a question: “Which of the many ‘unknown’ works do you like best?”

The cover of “La Caricature” from January 1883, celebrating 25 years of “Orphée aux enfers.”

I knew there were so many, and wanted to know where to start. The answers could be endless, simply because less than ten percent of Offenbach’s shows had a chance of being seen. He wrote nearly 100 of them. Besides Hoffmann the known were Belle Hélène, Orpheus, Périchole, La Vie Parisienne, and the Grand Duchess of Gerolstein. That is more like five percent. It is like an iceberg: only the slim top shows.

You heard overtures of other things, so you knew a little bit, but just that small part. And some of those overtures sounded wonderful: Karajan conducting Vert-Vert made you extremely curious to hear the entire thing.

In the course of my travels, I got to know many Offenbach experts. And the answers to my question were as varied as could be. Donald Pippin had his own small opera company in San Francisco: he made translations and performed whatever he wanted. His mission, or one of them, was to unearth unknown Offenbach. San Francisco had a tradition starting in the 1870s of being Offenbach crazy. The Tivoli theatre put on all sorts of his works. In fact, as soon as they were composed each of them was brought over to the “Paris of the Pacific” and put on in either English or French.

Donald Pippin. (Photo: pocketopera.org)

One thing was constant: poor Jacques never saw a penny. Copywrite laws either did not exist at all, or California was so far away from everything else that no one was taken to court. Pippin revived that tradition in the 1980s: besides all the famous ones, look at the list he put on: Bridge of Sighs, Brigands, The Cat who Turned into a Woman (La Chatte métamorphosée en femme, 1858), New Woman or Genevieve of Brabant, M. Choufleuri, Les Bavards, a double bill of the two one-acters Le 66 and Un mari à la porte, Madame l’Archiduc, another double bill of L’île de Tulipatan and Ba-Ta-Clan, and Barbe-Bleue. He even did a musical biography of Jacques.

The Online Archives of California

This was a staggering list, made more so when you know that Offenbach was not just his favorite; for over three decades, Pippin also performed around one hundred other works: Handel alone in the original. Obscure national operas from Poland and Bohemia became talked-about works for San Franciscans of the 1980s and 90s. Seventy of his translations, but not nearly all of them, are found at Stanford’s Music Archives, part of the Online Archives of California (OAC). You can find only nine “Offenbachs” there. Scroll down a bit; it’s right after the Mozart Collection. But many, including Trébizonde, are not included. You may be staggered as you read down the huge list of all those translations of operas. Many of them are gems and should be better known. And all of them are supremely singable.

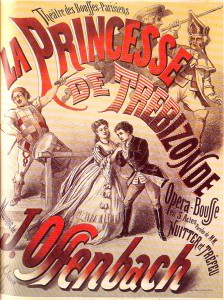

Poster for the first Paris production of Offenbach’s “La Princesse de Trébizonde.”

The one piece he was fascinated by, from what little he had heard of it, was the just mentioned La Princesse de Trébizonde. He wrote a translation that was so good I still remember parts of it, after 40 years. For instance, in Act One, when Trémolini first describes the Princess and the lottery to win a chateau, The Public answers “Ah! Que de plaisir pour ce soir!” Shea translates that for the new Opera Rara CD as “So much to hope for, so much to enjoy.” But I couldn’t help wanting to sing out Pippin’s, “To have a shot at the chateau!” As my work took me to Europe several times a year, I volunteered to go to Paris and try to find complete scores, with librettos. (Pippin had a hard time getting anything in complete form.)

It was during that trip that I met Antonio d’Almedia and befriended him and his lovely wife Lynn until Tony’s much too early death. Incidentally, d’Almedia’s favorite unknown was Madame l’Archiduc. “You can’t understand why it’s not done all the time,” he told me as he played some on his piano. He was envious of what Pippin was doing in San Francisco. And it was very likely that nowhere else on earth during the 80s and 90s was one able to hear so much Offenbach. With a slim orchestra and bare bones production values, the object was to let the piece proclaim itself. Virtually unknown outside of the SF Bay Area, Pocket Opera developed a fervent local following.

When Donald Pippin died two years ago at age 95, it was front-page news. When he showcased Trébizonde’s Princess in a run of ten, it was a highlight of my life. Offenbach got academic respect with the 2017 publication of Laurence Senelick’s Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture. His favorite “unknown”: La Princesse de Trébizonde. And had I not been lucky enough to hear a version myself, it would have been mine as well.

“Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture” (2018) by Laurence Senelick, together with the ground breaking “Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters” (1999).

The “Lighter” Baden-Baden vs. the “Paris” Version

And now, finally, we have as complete a version of La Princesse as is possible. Maybe we should say “versions” since there are actually two. The first, lighter version was done at Baden-Baden in the summer of 1869. Though the head of the Bad Ems casino commissioned it, Offenbach choose to move it to the more fashionable – now as then – casino at Baden-Baden.

He used several pieces from the never performed La Baguette. (As I wonder what that was about, my mouth waters …) From the first, he knew he had something special and instructed his two librettists to produce a work worthy of the Paris stage. He nearly always wrote music faster than his writers could keep up with him. Working at his summer home in Normandy’s Étretat, he constantly implored his two writers – Charles Nuitter and Étienne Tréfeu – to join him. “Neither of you are any good without the other; either both of you come or none of you!” he added. They came, but he still wasn’t happy.

This was an important work for him, and he took an active hand in the libretto himself. The July 31 premiere at the Prussian casino town was an international event. In the audience were several crown princes. But most colorfully sat the famed (or infamous) courtesan Valtesse de La Bigne. Her name may mean nothing now, but at that time “She Ruled Paris from Her Bed.” There’s an entertaining 15-minute YouTube biography of her (one in a series of “Forgotten Lives”). It was rumored that she could deny Offenbach nothing. His long-suffering wife put an end to that liaison with the help of a police inspector, as Keck tells us in his extremely interesting essay in the Opera Rara CD set.

That first version proved a sensation. Le Figaro’s correspondent salivated, “Offenbach has only included real gems …. He can present himself on Judgement Day holding Orphée in one hand and La Princesse de Trébizonde in the other, and be sure to be appointed the Good Lord’s Choirmaster.”

Offenbach himself however believed that the work needed more, and a great many changes were made. So many that the Paris premiere had to be postponed for months. The wonderful entire first act was composed, and the numbers from La Baguette were deleted completely. (Fortunately, these eight pieces can be heard on this new CD set, which, as far as I know, is the only place where they can be.)

Finally, on December 7, 1869, his beloved Bouffes-Parisiens theatre premiered the new 3 act version. That entire year can be called his annus mirabilis. Look at the list of shows which saw the light in 1869: Vert-Vert in March, La Diva a mere 12 days later, then the first 2-act Princesse in July. Finally, the year was topped off by no less than three in December: the 3-act Princesse on the 7th, Les Brigands a mere three days later, and finally La Romance de la Rose only one day after that!

Sheet music cover of a “quadrille brillant” put together by Strauss with tunes from Offenbach’s “Princesse de Trébizonde.”

After the Franco-Prussian War

The horrible years of the Franco-Prussian war and the Paris Commune were in the future the night of December 7, 1869 – the last year of peace, and of the Second Empire. People have said that the non-stop composition of eight works in the less than 15 months between L’île de Tulipatan and Les Brigands came as if Offenbach sensed that the end was near. There were still over six months left in 1870 before the catastrophe started, but it was as if Offenbach was preparing himself to move. He warned his friends from Bad Ems that summer that trouble was coming. (It was the infamous Bad Ems telegram to Bismark which set off the Franco- Prussian war!) Who knows? Great artists can sometimes perceive the future, and this is what Offenbach may have done.

In any case, the catastrophe was very personal to him: his fellow Frenchmen turned on him for the crime of his birth and accent. He fled and traveled for the next two years, to everywhere except Germany: he was ashamed of what had been done by the country of his birth. Historians have called what happened in 1870 the end of Europe’s greatest period. Ever since then, this view goes, Europe has been more like a museum than a dynamic society. If this is true, then La Princesse of Trébizonde gains an even greater meaning: the end of an extraordinary era.

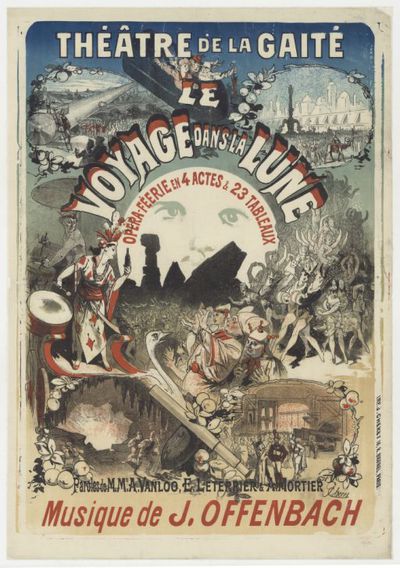

To be sure, Offenbach and others wrote some wonderful things in the 1870s. But the world of elegance, edge, and wit that made his name had altered. Works like Madame Favart (1878) are set in the nostalgic past (as is Lecocq’s 1872 Madame Angot), and ones like Le Voyage dans la lune (1875) are set on, well, the moon.

Poster for the “Voyage Dans La Lune” production at the Théâtre de la Gaîté. (Design: Jules Chéret)

These are wonderful works, but they are somehow disconnected from the life of the society they were written in – and that’s what audiences wanted: to forget those two horrific years and lose themselves in never-never lands.

One doesn’t want to burden the lovely shoulders of La Princesse of Trébizonde with too much deep meaning. But hearing the troupe say good-bye to the only world they had ever known, that short piece which ends the first act (Nr 15 on the first CD), “Adieu, baraque héréditaire” (“Farewell, oh tent of yore,” in the translation) … hearing that piece always moves me. They’ve just won a chateau and a new life. But the home they’ve always known (it’s implied for generations) and the only world they’ve known are disappearing and they are entering a new world that none of them understand. Isn’t that what Europe was about to do as 1870 began?

Offenbach’s “La Princesse de Trebizonde” on Opera Rara. (Photo: Opera Rara)

A Rare Gem

But enough of this high-flown talk. In the new Opera Rara CD, we have a rare gem. According to the essay by Jean-Christophe Keck (probably the world’s foremost living Offenbach expert), here we have the original, authentic work for very first time. And he knows this as he had just recently published his edition of it!

He tells how he had to track down the various autograph manuscripts, music in Offenbach’s own hand, dispersed in various branches of Offenbach’s descendants. He rather thrillingly writes of discovering how, “At the back of a ‘magic wardrobe,’ which contained a substantial number of autograph manuscripts, there was a folder labeled, ‘Trébizonde – Fragments et coupures’ (‘Trébizonde-Fragments and cuts’). This is where we found all the numbers dropped as a result of the changes made by the composer and his librettists between Baden-Baden and Paris.”

These are now heard for the first time at the end of the CD set. It will also be the first time you will hear those pieces from La Baguette (1862), with words by that immortal duo Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. To say that it was exciting for me to hear this music is an understatement. (Luckily, I was not expecting anything about the world-famous loaf of bread, or it would have been a let-down.)

Seriously, it is wonderful how Europe’s nooks and crannies are still holding precious things like autograph manuscripts or even full movies that had been considered ‘lost’ and yet turn up periodically in attics or archives. Because of these finds, we are able to hear Trébizonde in a way more authentic than it has been since the days when it was new. And that’s exactly what this marvelous new CD does.

There’s an old truism that making a poor production takes just as much time and efforts as making a great one. And with the first full recording of something whose glimpses have caused it to be beloved, we hope for the absolute best. When you think of what goes into it all: the right singers singing with the proper style, the orchestra and perhaps most of all the conductor, who sets the tone for the entire enterprise. To use the American expression, “we lucked out” with this, and did so in the extreme.

“Transport You Back to that Heady Night in December, 1869”

Conductor Paul Daniel puts it so very well: In a recording studio with a wall full of microphones, “You often feel a long way from live theatre, where these wonderful characters and crackling orchestra parts really belong. But my ambition throughout or rehearsals and recording sessions was for all of us to be on stage and in the pit, with our audience in the stalls thrilled and excited to see Offenbach’s latest creation. I hope that some of the sensations of those first nights come across. We’ve played as recklessly with the interplay of dialogue and music, and with some of the thrills and spills of the fairground in Offenbach’s extravaganza. We’ve also tried to capture the taut and compact acoustics of the Bouffes-Parisiens. (My emphasis.) What he set out to do, Paul Daniel did. His hopes that his Trébizonde, “Will transport you back to that heady night in December, 1869” have been fulfilled (as far as it is possible, of course).

I must say that the woodwinds stand out. There are no weak links in the cast. The title role of Zanetta, Anne-Catherine Gillet, is just perfect for her part. She’s Belgian. She got her start at a very young age on that lovely stage in Liège, the one with that city’s favorite son, André Grétry on a statue beckoning all in. (To me this is a magical theatre: I’ve never seen anything less than wonderful played there.) Zanetta’s love, Prince Raphael, is a trouser role sung here by Virginie Verrez. (French born but Julliard trained – something about her makes me want to see her in live performance.) Among the rest, again, there are no weak links. But some stood out: Trémolini, by French tenor Christophe Mortagne “who is in demand for character roles in major houses around the world” – and I can see why. He takes ‘small’ roles and makes them memorable.

The only non-European is Canadian Josh Lovell in the wonderful role of Raphael’s father, Prince Casimir. He does a great job with his famous “couplets about his cane.” It’s not fair to leave anyone out: Antionette Dennefeld, an Alsatian, is blessed with stunning looks to go with her voice. She makes the most out of a fairly small role. The same may be said for Katia Ledoux. I very much enjoyed Christophe Gay as Cabriolo.

All of the above, including conductor Daniel, are making their Opera Rara debuts here, with one exception: tenor Loïc Félix is wonderful in dual roles here. He has a lot of Offenbach recordings under his belt, and was on that marvelous Opera Rara double-CD of little-known Offenbach, entitled Entre Nous. Here is one cut with him:

Opera Rara does a tremendous job in giving us so many unknown treasures. The actual CDs are hard to find and expensive, but YouTube makes a present to us all. That just goes to show how much gold still remains in the mines. If you don’t know Entre Nous, do yourself a great favor. I fear I haven’t made sufficient praise to the music from the first version, from the previous summer in Baden-Baden. I can understand why it was greeted with such fervor: though in style it is not like the finished product we know, the music is entrancing in its own way. It never ceases to amaze me how much great music was written and then essentially thrown away, since it did not fit the project at hand, or was too long, or something happened to stop the show it had been written for.

Those last eight cuts on CD 2, comprising nearly 36 minutes of never-before-heard (by me) music weaved enchantment – at least to this listener. I had to listen to it a second time to realize how different it was from La Princesse we know. Please, ye gods of forgotten archives and attics, give us more Baguettes!

Superb Choral Work

Finally, the choral work throughout is superb. Director Stephen Harris deserves our thanks. Keck’s essay I’ve already lauded. If I were forced to complain about anything, it would be the translation. But that’s just because I still remember what Donald Pippin did so long ago. I don’t understand why the Stanford Archives do not include it. One day I hope to see it again, and I would probably fly to San Francisco if the new crew at Pocket Opera ever put it on again.

Josefine Gallmeyer in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt,” Vienna. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

We’re lucky to have two companies recording little-known gems for us now: Palazzetto Bru Zane does not set out to compete with Opera Rara, but both have done Offenbach: Bru Zane has La Voyage dan le lune, Maître Péronilla (can’t get too much rarer than that one!), and the great Marc Minkowski conducting La Périchole. But now that I’ve heard Opera Rara’s Princesse, I long to hear more of Paul Daniel’s baton work. (I can’t leave Bru Zane’s efforts behind without telling you about the extraordinary single CD called Offenbach Colorature with Jodie Devos, a Franco-Belgian like our Zanetta/Princesse here, Anne-Catherine Gillet. What do they put in the water there in tiny Wallonia?)

The solo album “Offenbach Colorature” featuring soprano Jodie Devos. (Photo: Alpha/Outthere Music)

As an example of how Offenbach can reach and entrance all sorts of people: I was driving in my convertible last winter in South Florida. Pulled up at a stoplight, I was playing (I think it was a cut from Mesdames de la Halle) and a Hispanic truck driver looked down and with shining eyes asked me, “Hey, what’s that wonderful music?”

In the meantime, opera companies performing in English should gain much by looking up any of the 70 works that are listed from the aforementioned Pippin collection.

Opera Rara deserves our most heartfelt gratitude for bringing this magical Princesse to life. A gap has been admirably filled. I know it sounds greedy, but please give us more! There are still around 80 – or maybe it’s just 60 – works that have not yet been recorded.

For more information about the Opera Rara double disc, click here.