James McLaughlin Smith

Operetta Research Center

23 December, 2017

Back in 1997, Michael Miller, the chair of the Ohio Light Opera Board of Directors, and president of the Operetta Foundation in Los Angeles, along with Emmerich Kálmán’s daughter Yvonne, began releasing a series of historic recordings of radio broadcasts from the 1940’s of the music of Emmerich Kalman, and they make for fascinating listening today. For reasons known only to him, the redoubtable Dr. Kevin Clarke asked me – a life-long friend of Yvonne Kálmán, but non-pro musically – if I would “feel like scribbling something down” with regard to the aforementioned. And I said, with some reticence, that I would love to give it a go. After all, what better way to honor the friendship than with a loving nod to the past that helped create it?

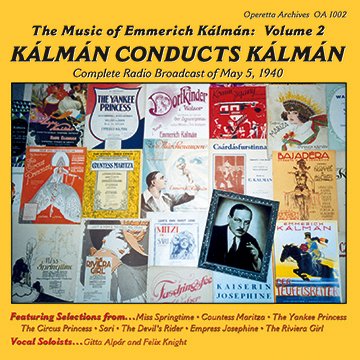

“Kalman Conducts Kalman”: A CD version of his 1940 New York City concert.

I would like to begin with the jewel of the collection: Volume 2, Operetta Archives (OA1002): Kálmán Conducts Kálmán. And the title says it all. He had Toscanini’s NBC Symphony to work with, not a bad band to have for your first radio gig in the States. In this delightful recording of a May 5,1940, broadcast from New York City (Sunday evening, before Walter Winchell), there are some stunning revelations that lift it to another level. It’s a virtual master class in conducting, at least with regard to the orchestral selections offered here, from this great composer’s prodigious output.

Those seeking definitive interpretations need look no further.

The first selection is the overture to Miss Springtime, a work which had a convoluted journey. Kálmán wrote it first, in Hungarian, as Zsuzsi kisasszony, about a country girl, Susie, who goes to the city to learn about life and love, only to realize home is where the heart is. New York soon called and it was anglicized as Miss Springtime. Then German entrepreneurs jettisoned the book and came up with Die Faschingsfee, retaining the Hungarian heroine, though now an incognito princess consorting with bohemians in Munich. This then gave birth to The Carnival Fairy.

Before I heard this recording, I had coincidentally become obsessed with the Köln recording of Faschingsfee by Peter Falk, and then Ohio Light Opera’s complete version of The Carnival Fairy, conducted by Steven Byess. The OLO performance of the overture, while nicely played, is quite languid about getting to where it needs to go, which would account for the 6 minute, 20 second playing time. Peter Falk’s clocks in at 5’30,” brisker certainly, more passionate perhaps, but not quite cohesive over all.

The “Fsschingsfee” recording conducted by Peter Falk.

Now it was time to listen to Kálmán conducting this same piece, and it was a good thing I wasn’t operating heavy machinery at the time. After a very few seconds of the full, opulent orchestral sound I was muttering to myself, “OMG, this is what it’s supposed to sound like!”

From the downbeat on, you sense an incredible urgency. The composer/conductor, at once thoroughly and assuredly in command, guides you into every part of the orchestration, pulling you through the threads, all of which are heard and felt. Then, before you can say, ‘where did that come from?,’ a lovely little waltz takes over, gains in importance, then thrusts you into a complete seduction and manipulation by Kálmán’s rubato culture: the ins and outs of tempi variables… I mean, yes, the notes are on the page, but this can only be fully realized through the conducting. Finally, we transcend it all for a powerful, majestic finish, the precise, insistent through-line having sustained, never let up, and left you in awe and a little breathless. All this in 5 minutes flat!

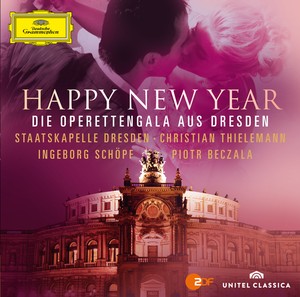

Next, the Intermezzo from The Yankee Princess (Die Bajadere). This operetta from 1921 is simply loaded with gorgeous, gloriously operatic music, especially all the ravishing, better than Borodin exoticism. For a comparison, I first watched a live performance on the fairly recent DVD of a New Year’s Gala performed by the mighty Dresden Symphony, conducted by Christian Thielemann (and, by the way, only a fool would fail to admit that the up-to-date sound recording leaves the 1940 Kalman broadcast in its wake).

The 2012 New Year’s gala from Dresden, conducted by Christian Thielemann.

It begins resolutely enough, with the right kind of snap, but then Thielemann comes to a full stop before the flute solo, and in the beautiful, exquisitely played slow section that follows, you can literally feel the steam escape from the narrative flow. He dawdles through the quiet beauty, never quite regaining the thrust, and robs the conclusion of some of its requisite power. Now for the Kálmán version, seat belts recommended. This performance seems to unfold organically, skipping the page entirely, and appearing fully-formed in the consciousness in a blaze of fervid, coherent sound, each aspect of the complex orchestration clear, precise, emphatic, explosive. There’s not even a nanosecond spent getting into the flute solo, followed by an unbroken flow of entrancing melody that lingers a bit in reflection, before building to a final outburst of rapturous lyricism. Thielemann: 6 minutes, 40 seconds; Kálmán: 5 minutes, 10 seconds. I rest my case.

The original 1921 cast of “Bajadere,” with tenor Louis Treumann as Radjami and Christl Mardayn as Odette. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

“Grand Palotás de la Reine,” from the 1932 Der Teufelsreiter (The Devil Rider). The score is largely unknown today, with this notable exception from the third act. It has been referred to as a “fiery gypsy dance” (they’re always “fiery,” right?), but sounds more like a Hungarian folk dance and variations. Once again I compared the Kálmán performance with the recent Dresden one by Christian Thielemann. The playing times are about the same, with the Kálmán only 11 seconds faster. Thielemann, with the huge, sumptuous Dresden forces going for him, treats the first dance too sedately, it’s pokey even (there go those 11 seconds), whereas maestro Kálmán, in full command of his emphatic dynamics, gets everyone up on their feet right away, with plenty of bounce and verve. The second section, with it’s wonderful bit of syncopation, finds them both on the same page, and it remains so, as they kick it into high gear for the fast and furious finale, virtuosic playing all around. It’s exciting as hell, and certainly explains why this is an ideal concert piece for a top-tier group. Both versions are admirable, but in the end, I believe I heard the story told better by the Hungarian.

A caricature of Gitta Alpar, as seen in a Berlin newspaper in the late 1920s.

Filling out the hour-long program are several vocal solos and duets featuring legendary Hungarian soprano, Gitta Alpár, and American tenor, Felix Knight, with Alpár the clear standout. Her voice, while a trifle ‘light,’ is full of warmth, style, charm, and feeling, and you quickly surrender, while also marveling at the effortless control, the ease and assuredness with which she produces bell-like tones of exceptional purity and clarity.

The one and only Gitta Alpar in her pre-1933 glory days.

As for Mr. Knight, well, his gallant style and tone are consistent with the period. He holds his own and does some beautiful singing here (but didn’t stop me from wondering what it might have been like with a darker, heavier sound as a counter to her sometimes aggressive sweetness).

“Say Yes, Sweetheart, Say Yes,” from Countess Maritza, Act 2 (“Sag’ ja, mein Lieb, sag’ ja”): This love duet is perfection, and a personal favorite. The violin/harp intro casts an orphic spell that leads us into the first verse and its sweet, gentle trade-off exchange between the two. Then comes the chorus melody, and it’s an achingly beautiful one, the slower, more drawn out the better (usually the tenor starts this, but here, the soprano has the honor). There are moments in the execution of this spell-binding narrative that call for hesitation-then hold- then release, that are, in Kalman’s hands, swoon-inducing, and lift this aural enchantment to sublimity.

Cover for the original piano score of “Zirkusprinzessin,” 1926.

And speaking of swoon-inducing melodies, perhaps none top this enduring one from The Circus Princess (Die Zirkusprinzessin): “Dear Eyes That Haunt Me” (“Zwei Märchenaugen”). Many fine tenors have succumbed to this rapturous outpouring, and here, Mr. Knight gives it his passionate all.

Next, there is a medley of “Love Has Wings” and “Loves’ Own Sweet Song,” from Sari (Zigeunerprimas). The first, “Love Has Wings,” is an unusual duet that’s ambitious in its operatic complexity, particularly the lengthy intro. Mr. Knight attacks the tessitura gamely, then midway Alpár chimes in, literally, with a peerless coloratura, to give this pairing some wings indeed. He soars right along with her, and a captivating waltz finale ensues. “Loves’ Own Sweet Song” is a big, bouncy, full-out waltz that has a familiar ring to it, although it breeds no contempt, only admiration.

“Why Is It All A Dream?” (“Heut Nacht hab’ ich geträumt von dir”) is a tango from 1930, written for the jazz version of Csardasfürstin produced at Admiralspalast Berlin. An altogether captivating song, beautifully, delicately handled by Alpár.

The jazzed up “Csárdásfürstin” at the Admiralspalast 1930, with Rita Georg and Hans Albers.

“You Are The One,” duet from Empress Josephine (Kaiserin Josephine): This is big, grand, vocally daunting music, given forceful, full-out performances by the singers, with solid, eloquent support from the maestro and his pliant orchestra. One longs to hear more.

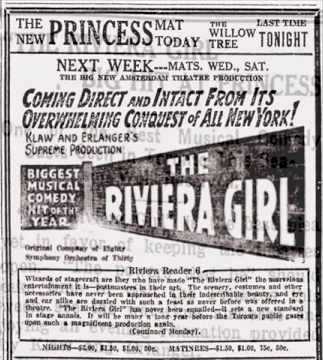

Newspaper ad for Kálmán’s “The Riviera Girl” on Broadway.

The Riviera Girl medley (Csárdásfürstin) is a delectable bonbon of greatest hits from this masterwork, interestingly arranged, crisply played with plenty of snap and brio, tasty, but transitory, really.

The concert was to conclude with “Play Gypsies, Dance Gypsies” from Countess Maritza, an epic tour de force blending folk and gypsy, to which Kálmán had added a thirty-second orchestral prelude to an already lengthy intro, making it one of the most tantalizing and protracted examples of musical foreplay ever. From the very slow, “haunting refrain,” of the violin solo on, layers are gradually added until, finally, the coaxing and cajoling explode…(well, not exactly)…

Remember, this was a live broadcast that needed to fit into its time slot exactly (Walter Winchell waits for no one). And so, just as Madame Alpár (it’s a duet here) began exhorting the ‘Gypy-sypies’ (for you Danny Kaye fans) to play!, and dance!, the announcer had no choice but to intrude and wrap it up. Csárdás Interruptus.

Emmerich Kalman and his family arriving in New York in May 1940. Yvonne Kalman can be seen sitting on her mother’s knee. (Photo: ORCA)

As an added bonus, and it’s a big one, there follows a brief radio interview with Emmerich Kálmán. In heavily-accented English, he speaks of his childhood, education and career with warmth and humor. In response to the interviewer’s remark that he recently put his pen to the most important work of his lifetime, Kálmán replies…”Yes. My declaration of intention of becoming an American citizen. You see, Mrs. Kálmán and my three small children all want to become 100% American…”

Yvonne once told me her earliest memories of her father were from their Manhattan apartment in the 1940s, when she, his youngest child, would sit underneath his piano while he played for visiting friends and dignitaries. After listening to this broadcast recording, thanks to Yvonne and Michael Miller, I too feel as though my spirit was able to linger beneath the piano for awhile and absorb his many-splendored gifts.

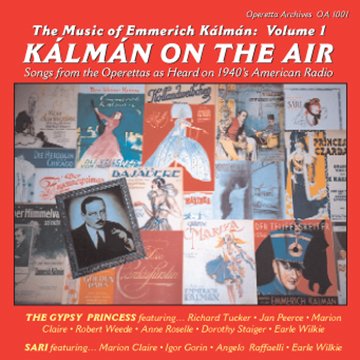

CD cover “Kalman on the Air.”

The Music of Emmerich Kálmán: Volume 1, Kálmán on the Air (OA1001) contains songs from the operettas as heard on 1040’s American Radio. “This CD is the first in a planned series that will pay tribute to this great theater composer by making available historical recordings of music from his operetta.” The object was to give radio audiences of the time condensed versions of shows, in this instance, The Gypsy Princess, and Sari. To give the songs a semblance of context, snippets of dialogue acted as connective tissue, providing the barest hint of a narrative. Radio actors were used for this rather than the singers. Sounds odd, but it kinda works in providing the illusion of having experienced a performance of the show rather than a concert of songs. A lot of fine singers are featured in these recordings: Richard Tucker, Jan Peerce, Robert Weede, Marion Claire, Anne Roselle, Dorothy Staiger and Earle Wilkie in The Gypsy Princess; Marion Claire, Igor Gorin, Angelo Raffaelli and Earle Wilkie in Sari.

The orchestra sound, generally, is big and brash, with a lush Hollywood overlay that sometimes threatens to swamp the delicate balance of the originals. But it’s undeniably exciting. Rearrangements abound, choral work is added, and most of it doesn’t sound remotely idiomatic. But it also doesn’t seem to matter. The performance levels are passionate, the singing exuberant, and these recordings, above all, are simply great fun to experience. And perhaps for many in the listening audience, a first-time introduction to the composer.

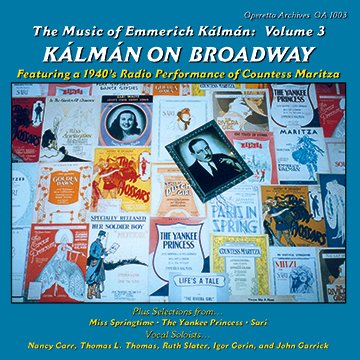

“Kalman on Broadway” from the series “The Music of Emmerich Kalman.”

The Music of Emmerich Kálmán: Volume 3, Kálmán on Broadway (OA1003) features a 1940’s Radio Performance of Countess Maritza, as well as medleys and orchestral selections from… Miss Springtime, The Yankee Princess and Sari. Vocal soloists are Nancy Carr, Thomas L. Thomas, Ruth Slater, Igor Gorin and John Garrick.

Scene from the original Broadway production of “Countess Maritza” starring Yvonne D’Arle. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

Another captivating listen. Abbreviated, and ‘fiddled with’, though it may be, this Maritza performance is ingratiating, full of good energy and plenty of sweet intention. It is followed by a highly eclectic array of fascinating interpretations of songs from other shows. I believe it can be said this composer’s work is at such a high level of taste and invention, it can survive any manner of reinvention.

And perhaps an effective way to approach this history would be to imagine that it is 1940, you and your family are in the living room, gathered around the radio, eager for a respite from news of a world all too ready to tear itself apart, yet again… and for an hour, at least, all are enveloped in the healing bliss, the life-affirming balm, the effortless certitude of a master at work.

Köszönöm szépen, Kálmán Imre… in the capable hands of your daughter, and the Millers, your legacy is alive and well!

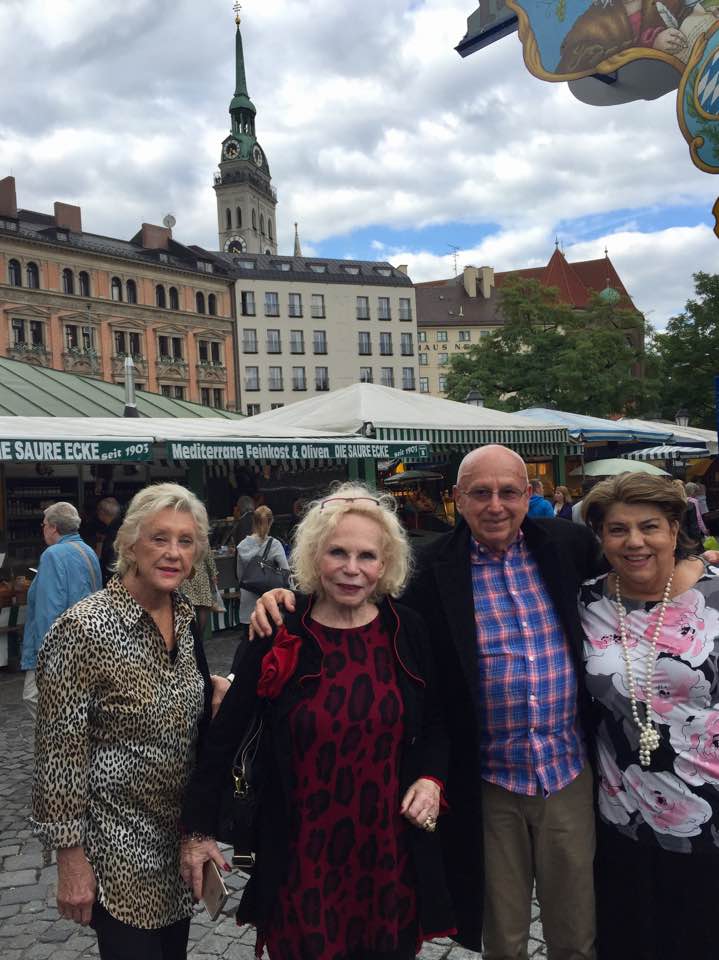

Jim Smith (middle) on tour in Europe with Yvonne Kalman (2nd from left) in 2017. (Photo: Private)

For more information on the three Kálmán CDs, click here for the online shop of Operetta Foundation in Los Angeles.