Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

22 January, 2019

Ivor Novello’s World War 2 hit The Dancing Years has finally been made available in a ‘first complete recording’ by JAY Records. The show is unique in the history of operetta because Novello wanted to tell British audiences the story of a Jewish Viennese waltz composer whose career is truncated by the Nazi invasion of Austria in 1938. We spoke with Novello’s biographer David Slattery-Christy about the show, its various versions (with and without Nazis) and the question whether Novello identified with the persecuted Jews because the Nazis also persecuted homosexual men.

A dashing looking young Ivor Novello in a typical publicity shot.

Mr. Slattery-Christy, what prompted Novello to tackle such a serious topic in a lush ‘romantic operetta’ just before the outbreak of war?

Novello in the 1930s had unleashed the full force of his talents as a composer onto a startled world – many had become used to him as an actor in comedy plays and as a matinee idol as the British Valentino on the cinema screen.

Because of his friendship with establishment figure Edward Marsh (Churchill’s Private Secretary) Novello would have been privy to news about what was going on abroad – specifically with the rise of Hitler and the Nazis in Germany. There is no doubt that he was horrified when he discovered that artists and composers who failed to meet the regimes ethnic or cultural standards were being persecuted, and having their work and music burned in public bonfires, finding themselves brutally interned in prisons or concentration camps.

On May 10, 1933, Nazis in Berlin burned works of Jewish authors, the library of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, and other works considered “un-German.” (Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Part of Novello, because of the privileged world he lived in, found this unbelievable and felt compelled to compose and write a show that reflected this injustice. It is clears that the seeds of The Dancing Years came from these unfolding events.

That Rudi Kleber, the main protagonist of the show, was a Jewish character added weight to the message that Novello was sending.

He could not allow any suggestion of homosexual sympathies (that reflected his own sexuality and Edward Marsh’s) because it was illegal at that time in the UK. Novello would have been aware that it was not only Jews being persecuted by the Nazis but also homosexuals, gypsies, disabled people and anyone who were considered ‘abnormal’ in the Nazi’s eyes.

The various triangles used by Nazi authorities in concentration camps the classify prisoners; among them the pink triangle for homosexual men. (Photo: United States Holocaust Museum Washington)

In your biography In Search of Ruritania you write that Noël Coward had a blazing row with Novello over remarks he had made on Chamberlain’s appeasement policy towards Germany. Novello had said that he was delighted that it was peace and not war. How did Coward change Novello’s view of things, and how did that affect The Dancing Years?

It is hard to understand today how desperate so many people were to avoid another war after so few years of peace, since the end of the Great War in 1918. Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement was widely supported because so many felt that anything was better than another conflict.

Winston Churchill in the Canadian Parliament, 30 December 1941. (Photo: Yousuf Karsh)

Churchill warned about the aims of Hitler and the Nazis during the first part of the 1930s, but nobody heeded him. In the end, as we know, Churchill was proved right. Noël Coward undertook intelligence work of sorts for the government during the war, but in the lead up to it – when appeasement was still rife and was something Novello supported because he hated the idea of another war – Novello found himself at odds with his friend Coward. During a meeting between the two, Coward was appalled at Novello’s lack of a detailed understanding of the political consequences, and Coward pointed out the devastating consequences for many living in Europe.

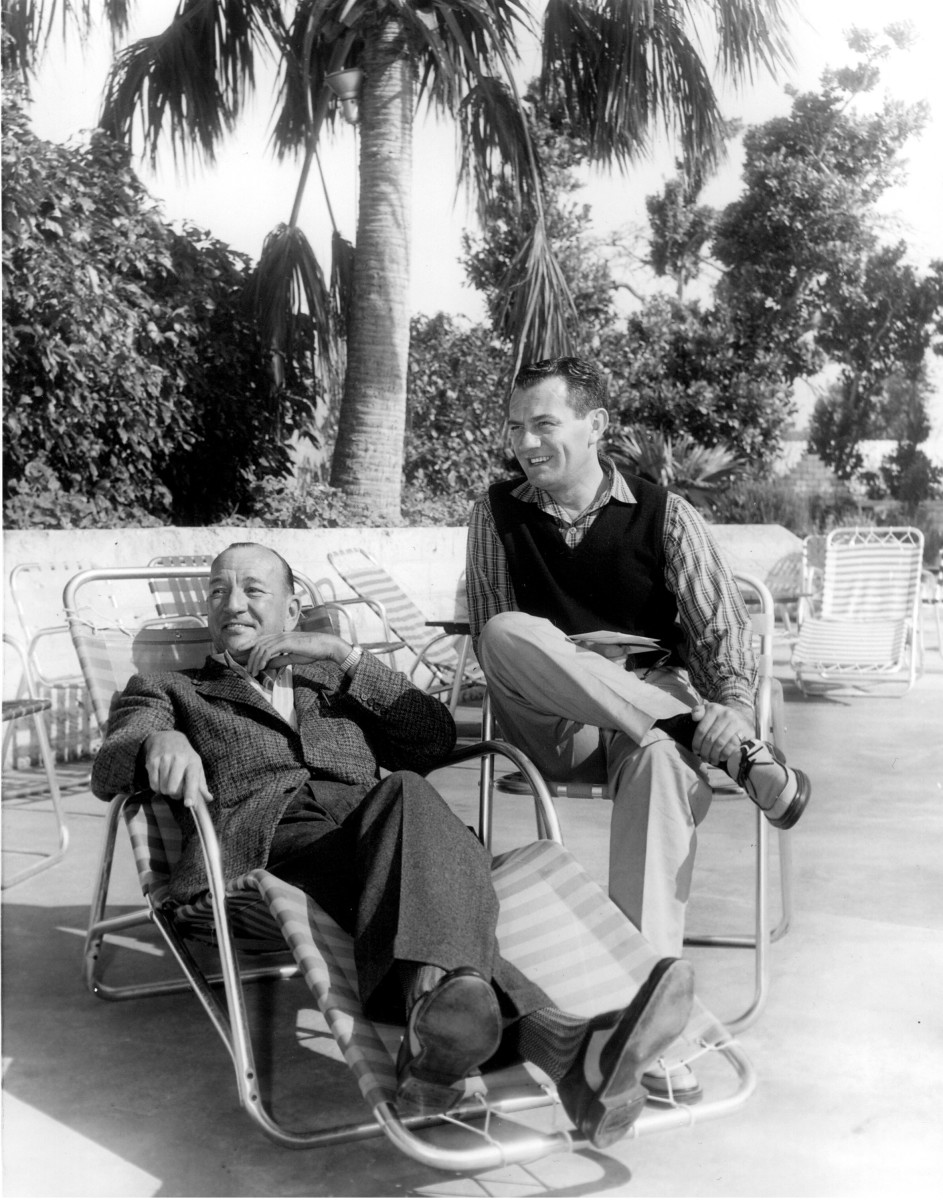

Coward with his life-partner Graham Payne.

Novello was chastened and turned his attention to creating an operetta that could handle this harsh reality but also give a message of hope to a wider audience – work on The Dancing Years progressed rapidly from this point in early 1938.

Did Novello identify with the mass persecution of Jews by Nazi authorities because of the similar persecution of homosexual men under §175? Could one see The Dancing Years as a metaphor on homosexuality?

Novello lived in a world where homosexuality was illegal in his own country. He was protected from the prejudice and hostility directed at homosexuals because of his wealth and celebrity. Many women who adored him had heard the rumours, but preferred to ignore any negative gossip directed towards their romantic ideal and fantasy. His popularity was immense, and if one considers the lack of available men after the Great War, and therefore a greater number of unmarried women and spinsters as a result, it is easier to understand how he came to represent their ideal man.

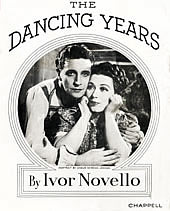

Cover of the score of Ivor Novello’s “The Dancing Years,” a “musical play in 2 Acts, 13 scenes and a Masque.” Published by Chappell.

Novello was aware of the persecution of homosexuals in Europe as a result of the Nazis and their brutal suppression and murder of anyone who failed to be considered normal. This and other aspects of his own life certainly became subsumed into Novello’s music. It was a way of expressing himself without the fear of being judged.

If you listen to his music there is an aching and longing there that is so heartbreaking. Some may call it sentimental, but I think that does his talent an injustice. It was a way for him to be himself – something he could not openly be in the outside world.

Through his music he really does touch your soul with an honesty and depth of feeling that many simply couldn’t reflect in their work. It is all the more poignant knowing what was happening in the world when he was composing it. The overture of The Dancing Years takes us on a journey of love, hope and yearning for a better world where everyone can simply be themselves. It transcends the everyday and the ugliness of politics and war.

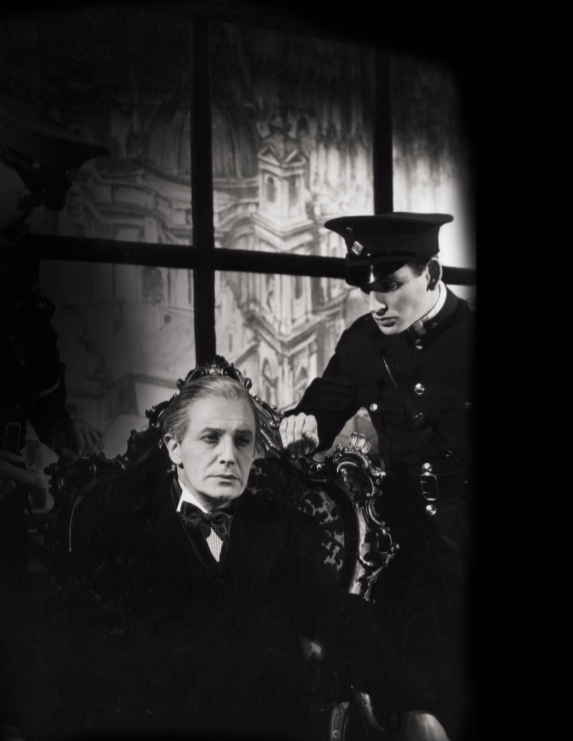

Ivor Novello being arrested as a “Jewish” composer in the original 1939 production of “The Dancing Years.” Photo from the JAY Records booklet, 2018.

Originally, Novello created a prologue and epilogue in which the audience sees the central character, Rudi Kleber, imprisoned by the Nazis. But that version did not pass the censor’s office. Considering how many anti-Nazi propaganda movies there are from Great Britain it’s astonishing that an anti-Nazi operetta could cause so many problems.

Novello wrote a famous prologue and epilogue for the original script of The Dancing Years that portrayed the brutality of the Nazis. Rudi Kleber was seen imprisoned for being Jewish and a composer that the Nazis did not approve of. It showed him being worn down, tortured but still defiant and believing that music and love could once again unite the world and rise up against hate.

In the UK the Lord Chamberlain’s Office was the government censor for every theatrical production. Before a play or musical or operetta could go into production the script had to be handed into the Lord Chamberlain’s Office for approval and licensing. Novello sent the script in late 1938, and when it came back to him it had been refused unless deletions were made. They insisted that the prologue and epilogue as written had to go and any mention or portrayal of the Nazis were to be removed. Why? At the time the government were still following the policy of appeasement and at this time they did not have any reason to see the Nazis as an enemy of the UK.

For political and diplomatic reasons they did not want any negative portrayals of Hitler or the Nazis as it could undermine what they hoped to achieve – avoiding war. As a result Novello had to reconfigure the script so the story took place from 1911 to the Austrian ‘Anchluss’ in 1938.

Christopher Hassall, Novello’s friend and lyricist for “Glamorous Night” and “The Dancing Years.” (Photo: Archive David Slattery-Christy)

What remained of the Nazi story at the premiere at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane on 23 March, 1939? Did the critics comment on world politics in their reviews?

By the time The Dancing Years reached the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, for it opening in March 1939, any mention or representation of the Nazis had been removed. It left just the central musical plot. Rudi Kleber an impoverished Austrian composer who is adored by a young girl, Greta, and they make a silly pact where he agrees to wait for her to get older so they can marry. He meets by chance the opera star Maria Ziegler and they fall in love. She wants to marry him but he remembers the promise he made to Greta and problems ensue.

When Greta returns all grown up they chat and laugh about their pact. Marie overhears and thinks they are in love and Rudi has betrayed her. She leaves immediately and marries someone else – but fails to tell Rudi she is pregnant with his child.

Many years later they meet again when Rudi is in prison. Marie brings the young boy and Rudi realises it is his son. Marie at this time is married to a high up official in the German army. Rudi explains to her the pact with Greta and that it was a game and they never intended to really marry. It was all a silly misunderstanding. Marie tells him she has begged her husband to help him escape. The story was still a powerful one, but it lacked real coherence as a story reflecting what was actually happening in the world because of the savage cuts insisted on by the Lord Chamberlain’s office.

Nobody was more angry and upset than Novello by this. The critics treated it less than seriously. London’s Evening Standard said: “He knows his audience so well indeed that, although we may quibble over details, we are forced to admit that in The Dancing Years he has given it a most vivid and glamorous entertainment – perhaps the most vivid and glamorous he has ever accomplished. Mr. Novello as Rudi strikes romantic poses, plays the piano better than he conducts and shows himself the incomparable stage architect in every scene. Miss Mary Ellis has never been better: a tender, passionate and utterly lovely performance. And Miss Roma Beaumont at Greta, captured our hearts from the moment she took the stage.”

Ivor Novello and Mary Ellis as Maria Ziegler in the original 1939 production of “The Dancing Years.” Photo from the JAY Records booklet, 2018.

There was a glimmer of recognition of the intent Novello had for the show that one critic from the News Chronicle noted: “And when in the last scene of all, in the captured Vienna of 1938, Mr Novello, now [as Rudi Kleber] now artistically decrepit, defies and conquers and brings the house down – why, this is only to show that Mr. Novello is astute enough to make the best of both world, the tinkles of 1911 and the tragedies of our own day.”

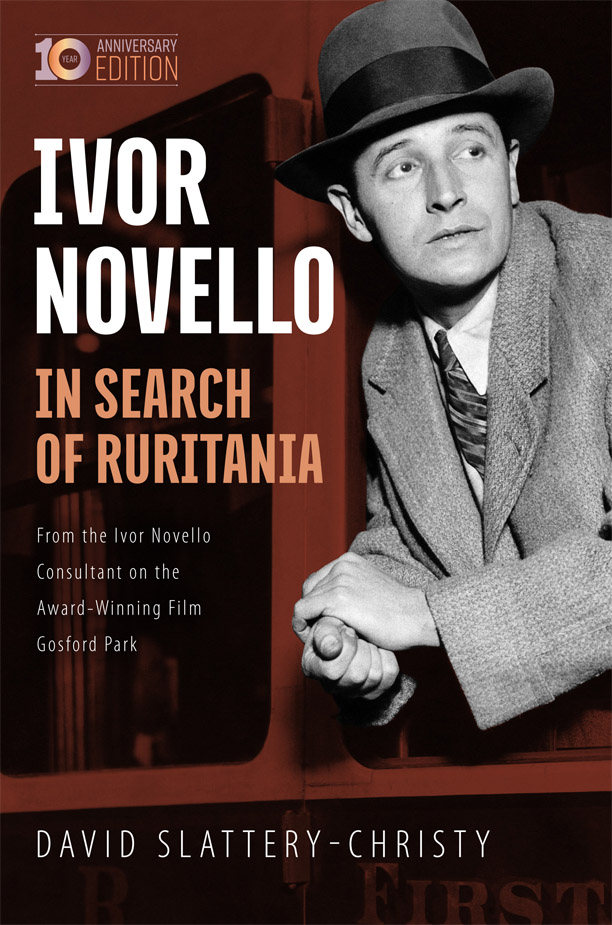

10th anniversary edition of “In Search of Ruritania.”

You also mention in In Search of Ruritania that Novello’s star soprano Mary Ellis was Jewish. Was that the reason he wanted her to play Maria Ziegler? Did she ever publicly speak out and condemn Nazi Germany?

Mary Ellis (Mary Elsas until she changed her name because it sounded too Germanic) tended to keep her Jewish heritage secret during her life at the time of The Dancing Years. No doubt this was because of the rising anti-Semitism in Germany during the 1930s and the obvious danger it could put her in. One has to remember that Noël Coward and Novello were both on the ‘immediate arrest’ list if the Nazis had managed to invade successfully – they would have all been shipped to concentration camps as undesirables. No doubt the story of the Jewish composer being suppressed and persecuted appealed to Mary Ellis as it was way to bring awareness to the injustice to the public. In later years Mary Ellis made her thoughts clear on how she despised the Nazis for what they had done to her country and its reputation.

A scene from “The Dancing Years” with the soldiers arresting Rudi Kleber wearing swastika arm bands. (Photo: Archive David Slattery-Christy)

After the initial West End run, The Dancing Years toured the UK and came back to London in 1941 to the Adelphi Theatre. It was now seen in a different version….

Once the original production of The Dancing Years was closed in September 1939 – all theatres were ordered to close by the government at the outbreak of the war – there was a period of uncertainty and expected air raids that would not materialise until later in 1940 when the Blitz began on London. Once the ban on theatres opening had been lifted Novello decided to take The Dancing Years on a tour of the country. Because war had been declared and the ruthlessness of the Nazis exposed there was no longer a government or diplomatic need to tread with caution in term of portraying Nazi thuggery. Novello applied to have sections of his script and have them wear Nazi uniforms and this was granted.

By the time The Dancing Years came back to London’s Adelphi Theatre in the early years of the war the Nazis had been fully reinstated – although by this time Novello did not feel the need to include the full prologue and epilogue as had been originally written because of time constraints and the fact that the show was so rehearsed in it didn’t seem to matter.

“The Dancing Years on Ice” as performed in Birmingham at the Hippodrome in post-WW2 times.

After WW2 the political element was completely scratched. Does that make the operetta just another ‘romantic’ love story without any poignancy? And why did post-war audiences in Britain not care for such a remarkable story when they applauded shows such as The Sound of Music with a similar basic plot?

It’s hard for us to understand how sensitive feelings were after the war, and The Dancing Years on Ice was, to be frank, a way for Tom Arnold (Novello’s friend and manager) to cash in on the romantic story and the music.

There was no appetite to make it too gritty or serious, as it would have limited the audience. Mr. Arnold would rather have a pretty, luscious blancmange of a show to make money than anything else. In that capacity it succeeded. However, it was a good example of how The Dancing Years was downgraded to romantic nonsense and not taken seriously. That is the show’s tragedy.

LP cover of “The Dancing Years” by Ivor Novello, showing the opening village scene. (Photo: Judith Wiemers)

Today it would perhaps be seen as the poor relation to Cabaret and The Sound of Music – but it was a forerunner to the genre and as the two most famous musicals were written in hindsight, The Dancing Years was written at the time things were actually happening. In that respect it is unique.

You have the original 1939 censorship libretto with the full prologue and epilogue. Would it be possible to perform that today, or are there legal restrictions?

There are, I would guess, perhaps two or three versions of the prologue and epilogue for The Dancing Years. All altered and amended as the years went on. I managed to have sight of the original versions some years ago and felt that, with some work, they were still very powerful – hindsight also allows one to appreciate the message that they wanted to convey to an oblivious public (at that time) about the Nazis.

Ivor Novello wiping off the make-up after a performance of “The Dancing Years.” (Photo: Archive David Slattery-Christy)

It was obviously a subject that touched Novello deeply in his lifetime and in terms of any legal issues in using the sections today there would be no problem.

In January 2019, the University of Leeds hosted an operetta conference that dealt with Nazi operetta history, one of the first times this happened in an English language context. In this changing climate regarding operetta, could a show like The Dancing Years stir new interest?

Because The Dancing Years was written as those historic events were actually happening it has to have a greater impact for student research than either Cabaret or The Sound of Music, as those shows, as I said, were written in hindsight. Novello was trying to show his audiences what was actually happening to artists and composers across the channel in Europe at the time they sat watching his show. Real events in real time.

Without The Dancing Years maybe shows like Cabaret and The Sound of Music would not have been written – audiences who saw the latter would have been influenced by the former? Discuss.

The CD cover for “The Dancing Years” on JAY Records, released in 2018.

The JAY Records version includes all the incidental music, but no dialogue, and in the inserted narration there is no mention of Nazis or the ‘Anschluss.’ Is any performance of The Dancing Years ‘complete’ without this?

Sadly, the romantic and sentimentalised version of Novello’s The Dancing Years has become dominant. All the focus on the lush and romantic story and melodies and eradicates the seriousness of the piece. As a piece of work it was one of Novello’s best, but sadly that did not endure. I am convinced that had Novello lived beyond 1951 and 58 years he would have revisited The Dancing Years and developed it to a degree where it would have sat in equal standing to shows like Cabaret & Co..

Tragically he never got the chance to do that and to be able to compete on a level playing field in terms of government censorship restrictions. The Dancing Years has never been seen complete – even by audiences at the time of its release as Novello was denied permission to present it in that way. Maybe that could be resolved with a future production that could encapsulate all the missing themes and script.

Ivor Novello originally played Rudi Kleber and the ‘impossible’ love stories with Maria Ziegler and the young Greta. Today, directors are handling the topic of homosexuality very differently in popular shows than in 1939. Should a modern production include/highlight the ‘gay theme’ of The Dancing Years? And if so, how could that be done?

In a way, Novello is a gay icon in the UK. His reputation suffered really because after his early death a lot of his close friends did everything they could to suppress any mention of his homosexuality. That was not anything unusual at the time, because homosexuality was illegal. Sadly, and ironically, that, and there determination to sentimentalise him, did more to damage his reputation and memory that protect it. It made Novello seem a bit boring and perfect – two things he was certainly not.

He didn’t have the wit and finesse of Coward and his comedy, but he composed exceptional music that even Coward agreed outshone his efforts at composing. Indeed one of Coward’s most famous comments was: “There are two perfect things in this world, my wit and Ivor’s profile!”

Autograph card, Ivor Novello.

In terms of The Dancing Years there is not a gay character in the show, Rudi Kleber is certainly not. Novello was a gay man playing a straight man, otherwise the whole premise of the misunderstood romance between Rudi and Greta as seen by Maria would not make sense. However, it is almost certain that for those in the audience there would be both men and women who were secretly in love with Novello as a personality. It was why he was such a bankable star.

Novello and Roma Beaumont in “The Dancing Years,” 1939.

Interpreting Rudi as a gay man who cannot say ‘in words as clear’ as when he plays music to his prima donna would that make the story of a ‘love affair’ with the teenage Gretl easier to handle – in a time when Gigi productions are presented without the Maurice Chevalier hit “Thank Heaven for Little Girls”?

In the context of the show Rudi Kleber was straight. I am sure there was a subtle subtext to some of the lyrics by Christopher Hassall (he was Novello’s lyricist) and their relationship, although Hassall was married, was very close – close to the point where Hassall’s wife would complain that when Novello called Christopher would drop her and everything else to go to him.

In terms of the plot of The Dancing Years the relationship between Rudy and Greta was innocent (and handled properly could still work) but where it becomes shaky is this: why would Maria leave imagining it to be true when Rudi could have just told her of the childish promise and asked her to play along? It is the biggest weakness in the romantic side of the story.

David Slattery-Christy (l.) at the BB3 studio for the Ivor Novello program. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy)

Last question: what is your favourite version of The Dancing Years on record?

For me, as a purist, and because I love the vintage sound, it has to be the original cast recordings with the Drury Lane orchestra conducted by Charles Prentice on HMV records, recorded in 1939.

I also heard a private recording of the first night curtain calls and Novello’s speech to the audience. It sounds like a fantastic first night reception, and the roars and cheers for him and Mary Ellis are spine tingling! It’s a real time travel wish moment – if we could just go back there for a few hours!

What’s coming up next?

You may be interested to hear that I just secured permission and script approval from the Novello Estate and Coward Estate for my new musical play Novello & Noël – A Marvellous Party! It includes original music of theirs, along with Lehár and Lionel Monckton, and is set in Novello’s flat atop the West End’s Novello Theatre. Novello, Coward, Graham Payn, Mary Ellis and Elisabeth Welch are all characters as they convene to enjoy one last marvellous party!

To buy the JAY Records edition of The Dancing Years, click here.

Oh, there are two rewrites of DANCING YEARS out there. The other one is by me. It doesn’t make any assumptions … but it does imprve the twee dialogue :-)

marvellous and so enlithening, thank you gh

Two years ago the Ohio Light Opera performed The Dancing Years with the prologue and epilogue, which I found very effective. The production was so favorably received that they are mounting their second Novello production this summer.

Fascinating – many thanks, Kevin. In retirement, Chas. Prentice was Director of Music for the Worthing (amateur) Operatic Society and I heard him conduct The Dancing Years, other Novello shows as well as G and S – in my extreme youth!

Fascinating to read. I saw a prologue used in Buxton a few years ago. Maybe the contrasts of shorter Nazi elements at each end of a full-length, highly romantic piece are too little, too late, somehow, out of a totally different style of show. In ‘Cabaret’ and’The Sound of Music’ the Nazi elements are integral to the plot.