John Groves

Operetta Research Center

20 January, 2019

Before the building of railways into London from the rest of south-east England in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, and the subsequent frequent, reliable (!) train service into the capital from the suburbs in the early evening and return several hours later, long runs of West End theatre productions were unknown. Gilbert & Sullivan’s Mikado achieved the longest run on any other production when it closed after 672 performances, but this was easily passed a few years later by the phenomenal success of Dorothy, which achieved 931, in three different theatres, the last of which, the Lyric, was paid for from the profits of Dorothy. At one time there were five companies touring the show in the UK, as well as in Australia, but when it was revived in London in the early 20th century it flopped twice. Since then it has been rarely performed, even by amateurs, especially as the score and orchestral parts were lost in Chappell’s fire in the early 1960s.

Poster for “Dorothy” production at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, 1887.

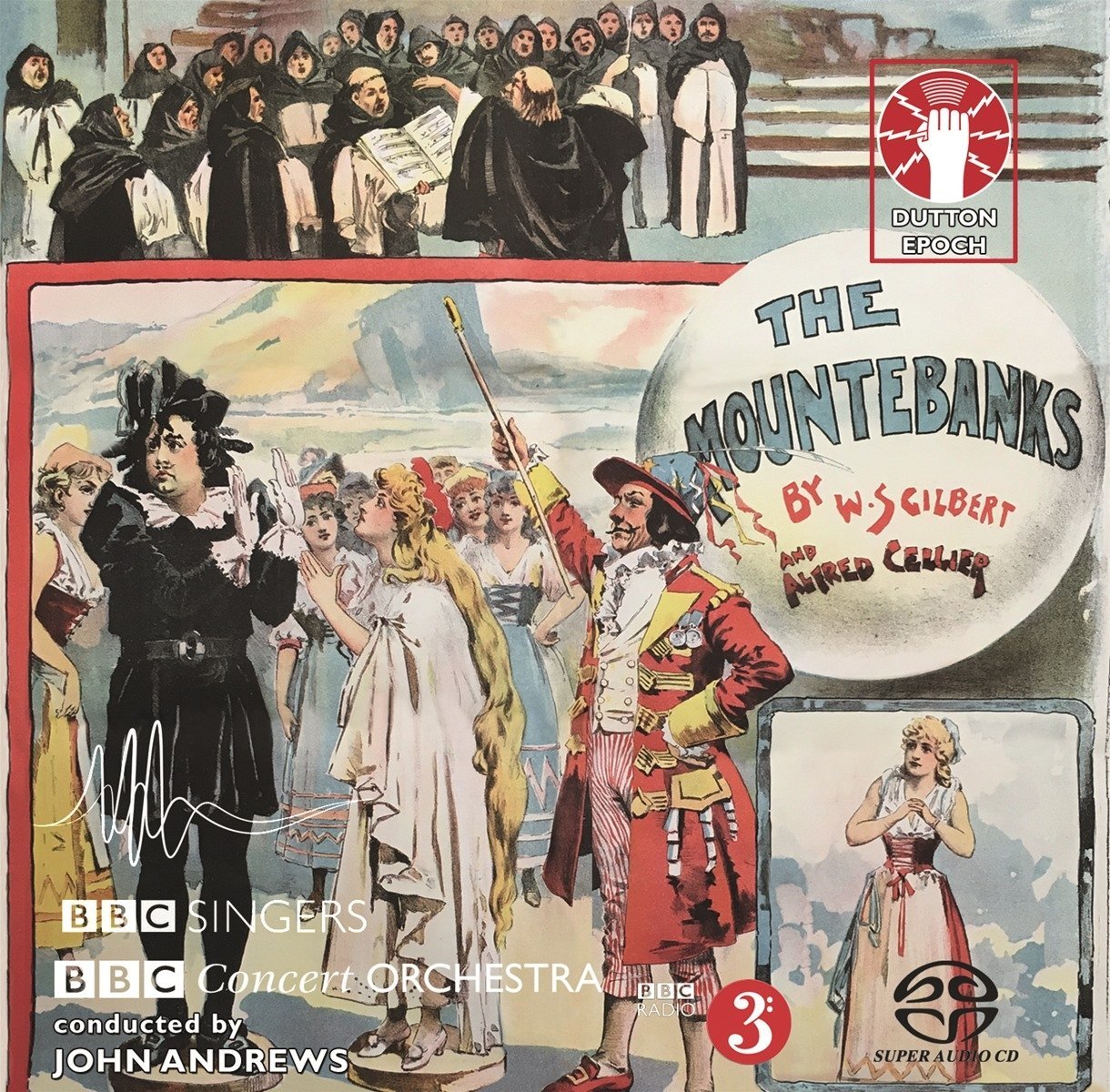

Alfred Cellier was D’Oyly Carte’s musical director at the Savoy Theatre for many years and composed curtain raisers and after pieces for the company as well as full length works. His final stage work, The Mountebanks, written with W. S. Gilbert, has also recently been successfully recorded.

The 2018 recording of “The Mountebanks” on Dutton Vocalion.

In 1876, Cellier composed Nell Gwynne which was deemed a failure! Never being one to waste ideas, several years later he asked B. C. Stephenson (the author of Sullivan’s The Zoo) to write a new libretto, fitting lyrics to already composed music, as Lorenz Hart was to do 50 years later for Richard Rodgers.

Alfred Cellier, H J Leslie and B C Stephenson (left to right). (Photo from H. Coffin, “Hayden Coffin’s Book,” London 1930)

This can explain why some of Dorothy’s lyrics can seem uninspired. The CD booklet notes tell us that in fact the book is very amusing.

The Richard Bonynge recording of Cellier’s “Dorothy” on Naxos.

In style, the whole show is very much like that of German’s Merrie England, which postdates it by some years. Cellier called it ‘a pastoral comedy opera,’ and he is correct.

At the time the music was found to be ‘pretty, graceful and charming,’ which is a good thing as, to be frank, it is all these things but not very memorable.

Whereas The Mountebanks, referred to above, contains complex musical finales to each of the first two acts, Dorothy does not. In fact Dorothy is a series of attractive short musical numbers, many of which are ensembles of all types, but no solo number for the singer of the title role, which seems strange.

The overture is the most ‘symphonic’ piece, lasting nearly eight minutes, but even that turns into a potpourri of melodies fairly quickly. The most well known number is possibly ‘Queen of My Heart’ which was actually interpolated after the first night from a previous show ‘Old Dreams’, for Hayden Coffin, one of the three original stars, the others being Ben Davies and Marie Tempest.

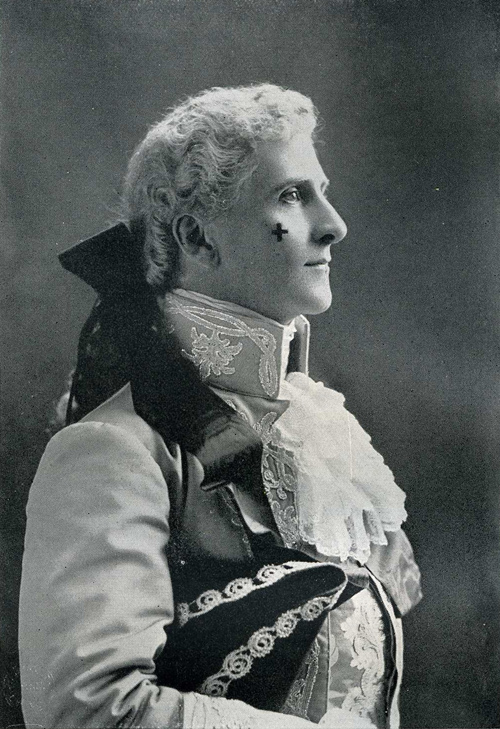

Hayden Coffin as Harry Sherwood in Cellier’s “Dorothy,” 1889. (Photo: Hayden Coffin’s Book / Alston Rivers, London 1930)

The plot concerns Dorothy who disguises herself in country attire and changes her name to Dorcas and, in time-honoured fashion, charms the naughty cousin who is refusing to marry her.

Victorian Opera, who is responsible for this CD, has recorded several British operas over the last fifteen years: Dorothy is by far the most successful, using, as it does, undergraduate singers from the Royal Northern College Of Music as the superb chorus: small with almost perfect diction, the tenors being especially impressive, mostly postgraduate young singers of the RNCM in principal roles and a small theatre-size orchestra, also drawn from the college.

I understand that a set of parts was found in Australia, using a reduced orchestra to save money, based on Cellier’s original.

The indefatigable Richard Bonynge is in charge of the proceedings, ensuring that there is a lightness of touch and style that is totally in keeping with what Cellier intended.

Majella Cullagh is Dorothy, demonstrating an attractive soprano. Lucy Vallis sings her female cousin Lydia, and Stephanie Maitland the innkeeper’s daughter Phyllis, with a surprisingly wide attractive vibrato.

Arthur Williams as “Lurcher” in “Dorothy,” 1894. (Photo from “The Sketch,” 1894)

The male roles are the most successfully characterised, the diction again being excellent. Michael Vincent Jones as Lurcher, the Sheriff’s officer, clearly understands his role, and his song ‘I am the Sheriff’s faithful man’ is one of the highlights.

Equally successful is tenor Matt Mears as Geoffrey (‘Though Born a Man’), whom Dorothy eventually marries, as is John Ieuan Jones as Sherwood, the Hayden Coffin role. (For more information Hayden Coffin click here.)

Furneaux Cook as “Squire Bantam” in Cellier’s “Dorothy”. (Photo from H. Coffin, “Hayden Coffin’s Book,” London 1930)

Edward Robinson as Dorothy’s father, Squire Bantam proves to have a very pleasant baritone in his only song ‘Contentment I give you’, even if he sounds a bit young for the role.

More historical detail can be found in Kurt Gänzl’s Encyclopaedia of Musical Theatre, Victorian Opera publish an illustrated guide to the opera, available from their website.

Some corrections to John Groves’s review of ‘Dorothy’ may perhaps be helpful.

1 ‘The Mikado’ did not achieve the longest nineteenth-century London run of any production other than ‘Dorothy’. ‘Les Cloches de Corneville’ ran for over 700 performances.

2 The orchestral score and parts of ‘Dorothy’ were not destroyed in the Chappell fire. The Naxos booklet carries a credit to “Warner/Chappell Music Ltd for exclusive access to the only band parts in existence”.

3 Dorothy does have what is essentially a solo number, namely ‘Be wise in time, O Phyllis mine’.

4 ‘Old Dreams’ was not from a previous show. It was an individual ballad with words by Sarah Doudney.

5 Ben Davies and Marie Tempest were not original stars of ‘Dorothy’. They took over from Redfern Hollins and Marion Hood in February 1887 – some five months into the show’s run.

6 A set of parts was not found in Australia. All that was found there was an orchestral selection. As above, the full orchestral parts for the recording came from Warner/Chappell.

Incidentally, much has been made of Cellier re-using music from ‘Nell Gwynne’ in ‘Dorothy’. However, it is very unclear how much or how little was in fact re-used. Of three published numbers from ‘Nell Gwynne’ in the British Library, only one was re-used for ‘Dorothy’, namely a soprano solo that, with new words and change of key, became Wilder’s ballad ‘With such a dainty dame’

There is certainly mystery regarding the orchestral parts. I am reliably informed that Ray Walker, the executive producer of Dorothy, wouldn’t even tell Richard Bonynge where he had acquired them in case he told someone else without Ray’s permission!

There is no mystery about the parts’ procurement. Research first took us to Australia, though we were warned about wrong cataloguing in their library. It is nonsense to assume that RW would not tell RB about the source as some sponsors knew early in 2018 at the time of the recording, and even before. RB knew the research details from the outset and so did AL above (6) otherwise he couldn’t have mentioned the fact..

One other number previously used is likely to be “Under the Pump”

“…Although the orchestral parts…were destroyed in a fire at the music publishers Chappell and Co in 1964, the location of a set of parts made for a reduced Australian touring production has allowed Richard Bonynge to create his own performing edition…..” (George Hall – BBC Music Magazine April 2019)

I’m afraid that George Hall is incorrect and the parts were not destroyed in the Chappell fire, as neither were The Emerald Isle”. Certainly, Victorian Opera and Richard Bonynge worked from a new full score which Michael Harris generated from the extant London band parts.We are pleased that the recording has been so well received by the Press.