Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

16 July, 2017

Viennese operetta at the beginning of the 20th century was a genre in transition, claims Stefan Frey in an essay printed in the CD booklet for Lehár’s Die Juxheirat. He lays out how the old masters of the ‘romantic waltz operetta’ all died by the turn of the century (Suppé, Strauss, Millöcker, Zeller) and a talented new generation that included Lehár, Oscar Straus, Leo Fall was unsure as to how best to proceed. On the one hand, the genre was taken over by popular new dances such as the cake-walk and other elements imported from the USA and American vaudeville – which translated into the smaller scale “Varieté Operette” made in Vienna. (Marion Lindhardt describes these exclusive and highly elitist varieté operettas as a continuation of the equally exclusive and elitist original opéra bouffe performances in Paris and Vienna.) The majority of ‘respectable’ mainstream critics thought this highly sexualized approach to operetta a “Chantantscherz”, i.e. a joke [Scherz] of the demi-monde or low-life cabaret type [Chantant]. It’s a typical reaction of so called conservative circles to anything too liberated and thus provocative.

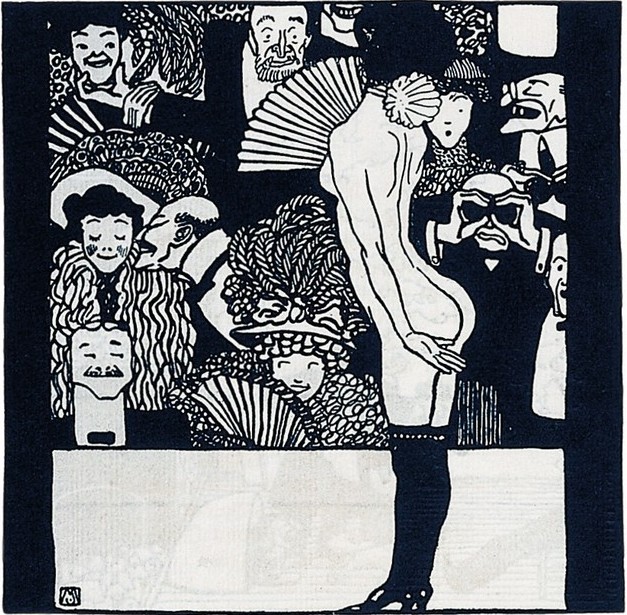

Moriz Jung’s illustration for the operetta cabaret Fledermaus in Vienna, 1907.

Frey’s thesis is that the young composers – lacking orientation – tried to go back to Offenbach and opéra bouffe in 1904 with parody shows such as the Juxheirat, with Straus’s Die lustigen Nibelungen, Lehár’s Der Göttergatte (an Amphitrion adaptation) or Fall’s Der Rebell. All of which were not partcularly successful. Then, according to Frey, came the Merry Widow and everything changed – “operetta went in a different direction.”

John Gilbert as Prince Danilo with the can-can girls in “The Merry Widow,” 1925. (Photo: Archive Operetta Research Center)

What is that new direction supposed to be, I wonder? Because if you compare the 1904 Juxheirat with the 1905 Lustige Witwe, there are many – very many – similarities. Lehár just didn’t manage to write the thrilling box office hit songs yet. The modern dance rhythms from America, on the other hand, were to define large parts of the future operetta business, especially after World War 1 when syncopation and jazz took over, leading up to Paul Abraham and Erik Charell’s big revue operettas as a crowning achievement. But there are many examples of pre-WW1 operettas by Lehár, Kalman and others that already reflect the ongoing transatlantic influence.

What’s true, however, is that we today have a very clear idea of how Lustige Witwe should be performed, which has little to do with the way operetta was performed back in 1905. And this idea of opera singers treating Lehár’s tunes to a “big sing” à la Tauber & Co., with no particular importance given to the dialogue (mostly cut to a minimum), is what you get on the new live recording from the Lehár Festival in Bad Ischl, released on disc by cpo.

The CD cover for Lehár’s “Die Juxheirat,” 2016 live recording on cpo.

It’s astonishing to witness such casting, as there is actually only one number in the entire score that might call for a legitimate opera voice: the lovely No. 6, “Lied des Arthur” with a flowing waltz refrain (“Herz, du bist bewegt! Neue Wonnen dich durchbeben”) pre-shadowing later famous Lehár tunes such as “Wär’ es auch nichts als ein Augenblick.“ (Arthur is sung here by Alexander Kaimbacher.) All other characters in this highly amusing play by Julius Bauer are more of the “Chantantscherz” type. Yet in Ischl, none of the roles is cast with such a chantant performer, certainly not the two central gentlemen: Jevgenij Taruntsov as a rather strained Harold von Reckenburg and Christoph Filler as his driver Philly Kaps. (The latter gets to sing a horribly updated act 3 couplet with Trump, Batman, Sissy and drug dealers getting a mention.) For the rest, it’s also young opera singers all-around who sing adequately well, even with clear diction (Maya Boog as the billionaire’s daughter Selma and Anna-Sophie Kostal as her opponent Juliane von Reckenburg). But without any noticeable humor to get the many jokes in the lyrics across. And to bring any linguistic variation to the refrains. It’s just “sing, sing, sing.” And the linking dialogue is equally humorless, to the point of being bland. You would never guess from this recording that any element of the show could have ever been considered up-to-date and subversive, edgy or even particularly witty. Let alone sexually daring. The singers are as neo-prude as Facebook.

Lehar in his study in Ischl, at the piano in 1910. (Photo: Die Villen von Bad Ischl/Amalthea)

As a result, this recording conducted by Marius Burket with the Franz Lehár Orchestra is another fully wasted opportunity to bring a fascinating show back to life because the casting department in Ischl (and cpo) cannot fathom that modern operetta – including non-Tauber operettas by Lehár from this early era – call for a totally different kind of ensemble. Today, you’d probably say it needs musical comedy people and cabaret artists with character voices to make the score and story sparkle.

Painting by J. C. Leyendecker of a chauffeur escorting a lady around.

To be fair, this CD is far better than many earlier cpo operetta enterprises, if you think of the horrendous Perlen der Cleopatra. But given the many – many! – amazing moments in this score, the gender issues discussed, the women’s rights issues, the fascination for fast cars, the hilarious same-sex marriage element (which is the “Juxheirat” of the title, i.e. the possibility of two women marrying by mistake), the Tristan and Lohengrin parody etc., it’s a shame that the Ischl team have not dared to steer away from so called “traditional” operetta performance practices. Instead, you get a lackluster reading of the piece that’s missing true star power – which Juxheirat had in 1904 with Alexander Girardi as the fast-driving chauffeur Philly. Who seduces and kisses his boss, Count Harold, at a crucial point of the story.

Bottom line is: Die Juxheirat is worth knowing and performing, it offers much more in terms of opportunities than is audible here. Also, the change Stefan Frey claims happened in 1905 is not as radical as he says, because the Juxheirat is a clear stepping stone for the next show, Die Lustige Witwe. And Leo Fall further developed many of the issues dealt with here in his highly successful Dollarprinzessin, which was an international hit of the first order. (Also awaiting a proper modern recording, preferably not from Ischl.)

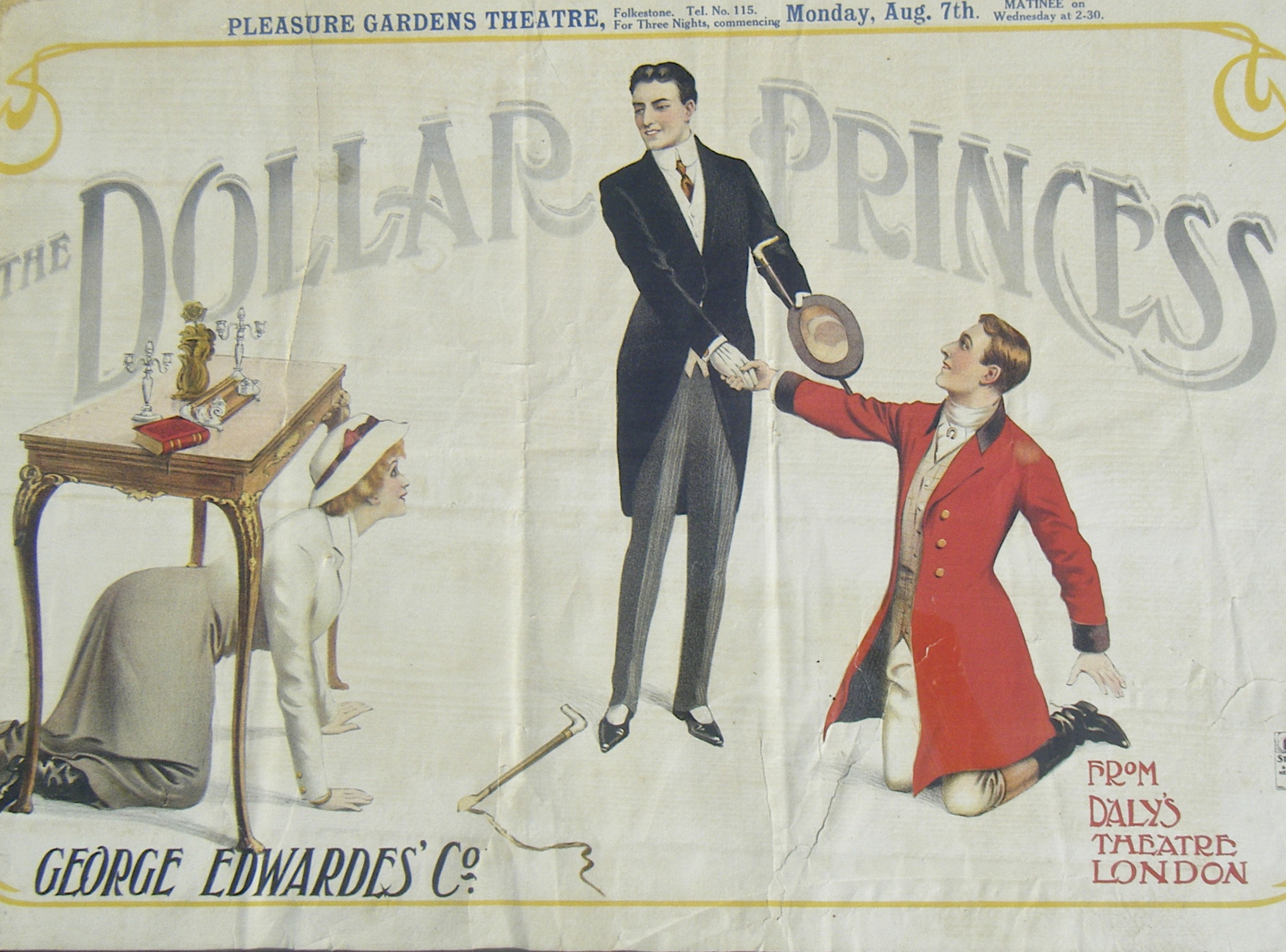

Poster for Leo Fall’s “The Dollar Princess,” 1911.

It kind of makes me sad to witness that such young artists – singers and conductor and stage director – have so little faith in the genre and its possibilities that they dare not steer one millimeter away from paths that have been labeled old-fashioned for decades now, while at the same time researcher like Kurt Gänzl, Marion Linhardt and even Stefan Frey have written extensively about how ‘original’ casting was once done, and could easily be done again. Apparently, no one in Ischl (and comparable other places) bothers to take such research seriously. It’s despressing and says a lot about the state of operetta today in many self-proclaimed operetta centers of the world.

For more information on the historical background of the story and a full plot outline, click here.