Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

8 May, 2015

The 8th of May, 1945 was a sunny Tuesday in the Third Reich. It was the day General Hans-Georg von Friedeburg signed the total and unconditional capitulation of Germany. It took 40 years until the German president, Richard von Weizsäcker, officially proclaimed that this was not just a day of defeat, but a liberation – the start of a new era. It took another 30 years until a 93 year old former SS officer went to trial and publicly asked for forgiveness for the things he did in Auschwitz. What did not happen, on a wider scale, is liberation from the operetta ideology the Nazis established in 12 long years. Their politically tinted ideals for the art form live on and on; they are hardly even discussed, only accepted as the still-standard.

The poet Jewgeni Dolmatowski in Berlin, May 2, 1945. Photo by Jewgeni Chaldej © Collection Ernst Volland and Heinz Krimmer, Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum.

When Barrie Kosky was asked at a conference in Berlin this year what he thought about the operetta performances of conductor Christian Thielemann (who performs the genre once a year at the Semperoper Dresden), Kosky’s famous answer was: “So furchtbar, so furchtbar. Der Mann ist ein Genie mit Bruckner und Wagner und Strauss. Einer von den besten Dirigenten in der ganzen Welt. Aber so ein Missverständnis! Und es klingt wie im Dritten Reich.” If you do not understand German, let me translate this: “So horrible, so horrible. The man is a genius with Bruckner and Wagner and Strauss. One of the best conductors in the whole world. But such a misunderstanding. It sounds like in the Third Reich.”

What Thielemann does, in concert, on TV, on DVD and CD, is: he presents operettas such as Lustige Witwe and Csardasfürstin with expensive opera stars, right down to the smallest role, and interprets the scores by Lehár and Kalman as if they were blown-up operas without any erotic or political edgyness. His aim is to “elevate” operetta to an opera level. It’s an aim the Nazis officially proclaimed too, e.g. Hans Severus Ziegler (the man who organized the Entartete Musik exhibition). His words in a Reclam Operetta Guide of 1939 were that operetta is nothing other than a “Singspiel” and a little sister of opera. He adds: “It’s a harmless art form, giving relaxation to those hard-working classes in society who need a few hours of rest from everyday life.”

The Nazi’s dumbing-down approach of operetta, combined with their elevating approach to pseudo-opera level, continued without the slightest intermission after May 8, 1945. This was due, on the one hand, to the fact that the operetta people in Germany mostly claimed to be “apolitical” and went straight back onto the stage and into the film studio to make exactly the same kind of operettas they had produced before. The exiled composers and librettists, stage directors and actors mostly did not come back to Europe until the end of the 1940s. By that time, it was nearly impossible for them to re-start their careers, or re-establish a performance style that was eradicated by the Nazis. The network of people who had taken their place between 1933 and 1945 was so tightly knit, that most home-comers gave up and retired. Even a man such as Erik Charell who did make an attempt to rekindle old performance traditions with Feuerwerk in 1950 gave in, defeated by the fact that the “old mummy of Nazi operetta” could not be overcome (as the Süddeutsche Zeitung poignantly put it).

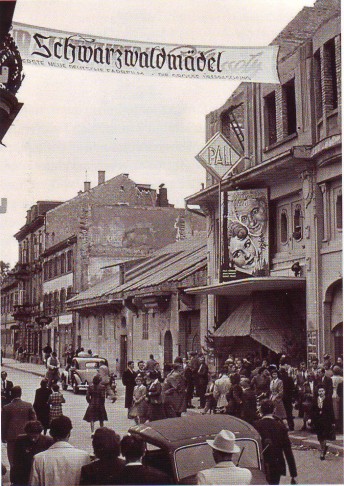

German audiences going to see the movie version of “Schwarzwaldmädel,” while the country still lies in ruins in 1950.

The other reason for the indisturbed continuation of Nazi operetta ideology is that such a harmless and mindless approach fitted well with post-war times. People now, more than ever, needed a few hours of uncomplicated happiness that were free from political battle and did not pose questions of guilt or “how much did you know of what went on in Germany before 1945.” The operetta boom of the 1950s and 60s presented the genre as a “Heile Welt” that you could turn to, for comfort.

Even though German society has drastically changed, meanwhile, this dumbed-down operetta tradition, combined with the ideal of elevated-to-opera-level, is still very much alive, wherever you look in this country: it’s what you are (mostly) presented with at the Staatsoperette Dresden, the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, the Gärtnerplatz Theater Munich, the Volksoper in Vienna; it’s the standard at most opera houses presenting operetta with their ensembles. And it’s certainly the standard on most modern CDs by companies such as CPO or Capriccio, containing radio productions by WDR in Cologne of Bayerischer Rundfunk in Munich.

The new, and temporary, Metropoltheater in East Berlin, in Schönhauser Allee. In the midst of the Sovjet occupied zone.

The only one who tries breaking free from this, on a major scale, is Barrie Kosky at his Komische Oper. But even there, star studded productions such as Ball im Savoy are cast – apart from Dagmar Manzel and Katharine Mehrling – with opera singers from the house ensemble. (Which is probably why their Eine Frau, die weiß was sie will was such a joy: no opera singer near or far!)

On a research level, the topic was not really discussed until 2005 when Operette unterm Hakenkreuz happened. The collected essays from that Dresden conference try to shed some light onto the matter. And I recall the strong reaction of conductor Ernst Theis back then, at the conference, when he realized that his way of performing Johann Strauss at the Staatsoperette was more or less in sync with Ziegler’s operetta ideology. Another illuminating book, from 2002, is the catalogue “…dass die Musik nicht ohne Wahrheit leben kann”: Theater in Berlin nach 1945 of the Stadtmuseum Berlin. There are major operetta essays in there on the situation in East and West Berlin after 1945, demonstrating how Nazi stars and tradition went on, undisturbed, after the collapse of the Third Reich. There are also fantastic photos and posters reproduced in that catalogue.

Displaced Persons after the liberation of Berlin, May 1945. Photo by Boris Puschkin © Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum.

If you consider the flood of publications and exhibitions commemorating May 8, 1945, it’s somewhat astonishing that none of the major operetta players in Germany or Austria have deemed it necessary to do anything of their own to discuss this special date. On the contrary, they take operetta out of the discussion, as if the genre and the way we experience it today has nothing to do with the capitulation and liberation of Germany. And with the sole exception of Johannes Heesters none of the famous Nazi operetta stars ever went on record saying “I am sorry for what I did before 1945.”

At the Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) in Berlin you can visit the exhibition 1945 – Defeat. Liberation. New Beginning until October. It shows “Twelve European countries after the Second World War,” including The Netherlands; plus Germany and Austria of course.