Charles Jernigan

Jernigan's Opera Journal

1 March, 2015

I have never seen Kismet, the 1953 musical, although like everyone else of a certain age, I know some of the songs – ”Stranger in Paradise,” “And This is my Beloved” and even “Baubles, Bangles and Beads.” So I was interested when Loveland Opera Theatre announced it as their major production of 2015, even though I generally think that opera companies should stick to opera, not that any opera company ever listens to my opinion. However, a little research shows that Kismet has a remarkably operatic – or at least a classical music – pedigree. I already knew that Kismet owes its hit tune “Stranger in Paradise” to Borodin’s opera Prince Igor, but I was not aware of how much of the score (virtually all of it) comes from Prince Igor and other Borodin works.

The logo for the original “Kismet” production, 1953. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Kismet (which means ‘fate’ or ‘destiny’ in Turkish and other languages) has a complicated story which sounds like an amalgam of The Mikado, Turandot and lesser known works like Rabaud’s Marouf, a once popular opera which concerns a poor man/trickster who marries a princess. In this case it is the young Caliph who is in disguise and who falls in love with the impoverished daughter of a poet named Hajj, who pretends to be a beggar who becomes a (phony) great magician, all through the mystery of kismet. Perhaps it’s better not to try and figure it all out before seeing it, but the book (by Charles Lederer and Luther Davis) is based on a 1911 play by Edward Knoblock, and it all sounds like it ought to be out of the Thousand and One Nights and probably is. It takes place it Baghdad, which, given current events, is a fantasy Baghdad indeed. In the musical, everything ends happily.

CD cover of the Original Broadway Cast recording.

The play by Knoblock was a big hit as well, and it was made into a movie more than four times times starting in 1914. Otis Skinner, a famous actor in his day, made a specialty of Hajj, the beggar poet, and Loretta Young was in the now lost 1930 version, which caused something of a scandal because of the harem scenes. Marlene Dietrich and Ronald Colman starred in the 1944 film version.

Kismet, the musical, is really a pastiche, an honorable genre practiced by Handel, Rossini and many others in centuries past, right down to the Metropolitan’s recent, highly successful, baroque pastiche The Enchanted Island. A pastiche brings music intended for different works, sometimes by different composers, together for a new work to a new story and text. Sometimes the composer himself reshapes his own work, e.g. Handel. Sometimes arrangers and adaptors take existing music by others. Borodin’s adaptors were Robert Wright and George Forrest, who already had experience with another successful Broadway pastiche, The Song of Norway, which had used the music of Edvard Grieg for another Broadway extravaganza full of great tunes and spectacular scenery.

But Kismet didn’t start on Broadway; it started in Los Angeles where the Civic Light Opera commissioned and first produced it. It moved on to San Francisco, and opened on Broadway in December, 1953, in the midst of a newspaper strike. Because the producers were unable to rely on newspaper advertising, they turned to the new medium of television to hype the upcoming production, and it worked. By the time the strike ended and the major critics had their (mostly negative) say, Kismet was already a hit.

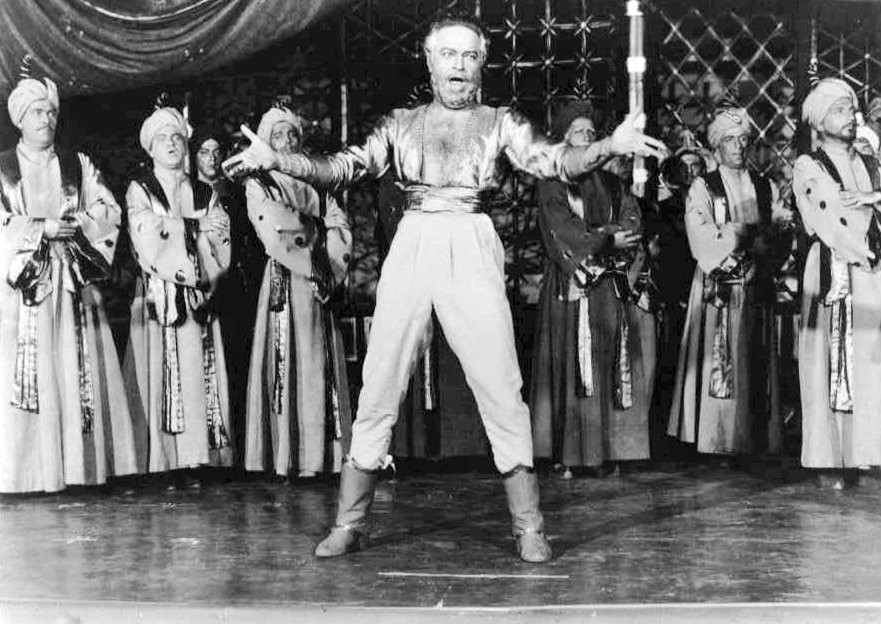

It won three Tonys in 1954, including Best Musical and Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical (Alfred Drake).

It had a successful run on London’s West End and was made into a big Cinemascope movie directed by Vincente Minellli in 1955. There was a TV version in 1967 with José Ferrer and Barbara Eden, whose most famous endeavor was another Thousand and One Nights-type TV fantasy, I Dream of Jeannie. Also in the cast of the TV production was the beautiful Anna Maria Alberghetti, who started her career as an opera singer and crossed over into musicals and movies.

Kismet’s operatic roots must have appealed to New York City Opera, which produced it in 1985. A recording of that production came out which had major operatic credentials with primary roles taken by Samuel Ramey, Ruth Ann Swenson, Jerry Hadley and Julia Migenes. There was even a pastiche of the pastiche in the 1970’s when the Middle Eastern context was moved to Africa with a new title, Timbuktu!, and with a new star: Eartha Kitt.

In other words, the Russian composer Borodin’s music has served a LOT of geographical venues including medieval Asia, ancient Baghdad and Africa with a LOT of different singers and actors whose experience has ranged from the opera stage to the Broadway stage to movies to TV, and now to the intimate stage of the Rialto Theater in Loveland where LOT (Loveland Opera Theatre) is going to produce it in several performances at the end of February and March 1.

Alfred Drake in the original 1953 Broadway production of “Kismet.” (Photo: Wikipedia)

Richard E. Rodda has specified the Borodin sources for the music, and besides three pieces drawn from Prince Igor, there are pieces from the composer’s Symphonies 1 and 2, from the first and second String Quartets, from the tone poem “In the Steppes of Central Asia” and from the Petite Suite. Wright and Forrest, the adaptors, used one of their pre-existing songs for the song “Rahadlakham” and wrote some connecting music, but everything else, as I understand it, is Borodin.

Although there have been a few major revivals over the decades since 1953, Kismet has not been done that often and is not common fare in dinner theaters or light opera revivals.

“KIsmet” at the Loveland Opera Company, Colorado. (Photo: LOC)

It is complex, and as produced originally, it requires a lot of resources, although there have been successful pared-down versions. It would seem that the total fantasy of the plot would not cause controversy, but in 2011 it was banned in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, when a local high school planned to do it. Seems that the school principal and some enlightened locals thought that a play about Muslims in a fantasy of ancient Baghdad would insult the memory of those killed in the 9/11 attacks.

So the chance to see it doesn’t come around that often. Really, how can you go wrong? An amusing fantasy with a beautiful poor girl who becomes a princess, a Caliph in disguise, a trickster poet–and the bad guy gets his just desserts. If you are a fan of the Broadway musical, you have a fairly seldom-revived classic. If you like opera, you have all that luscious Borodin. And it was banned in Johnstown!

Read the original article here.