Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

15 April, 2020

The only way I can describe my reaction to this attractively packaged new Franz Lehár reader, published to coincide with the 150th birthday of the composer on 30 April, is this: I am speechless. The publishing house Böhlau has managed to secure the financial support of the region Upper Austria/Oberösterreich who wish to present themselves as a “Kulturland.” They have financed the printing of this 230 page collection of essays. Which is a kind of “extra” next to the equally new Lehár biography published by Stefan Frey, also at Böhlau. While the Frey book was a rewarding read, full of fascinating details and well balanced thoughts, “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz”: Ein Franz-Lehár-Lesebuch is an embarrassment.

A burned piano in Vienna. (Photo: Adrian Swancar / Unsplash)

Of course, the basic idea of having eight essays highlighting different aspects of Lehár’s life and oeuvre is a good one. A very good one, actually. If you read Stefan Frey’s book closely you’ll notice that there are various topics he touches upon briefly that would benefit from a more in-depth investigation, e.g. a text on the film versions of Lehár’s operettas. Frey calls the Erich von Stroheim Merry Widow (1925) with its “excessive sex orgies” the “most successful and best Lehár film adaptation ever.” (I’d wholeheartedly agree.) Frey also mentions the Ernst Lubitsch Merry Widow (1934) starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald as a positive example, but leaves out the many not-so-positive versions that followed. There’s a lot to say about recycling Lehár for film and television in different eras and different countries. What did they do for our understanding of “operetta” and/or Lehár?

The seductive tango of John Gilbert and Mae Murray, one of the most striking scenes from “The Merry Widow” movie 1925. (Photo: Archive Operetta Research Center)

Or, to give just one other example, Frey mentions that Lehár’s private life and love affairs were briefly threatened to be exposed in 1937 in a blackmailing scandal, initiated by actor Arthur Guttmann (husband to operetta diva Mizzi Zwerenz). Lehár managed to stop court hearings by writing a highly anti-Semitic letter – as a cry-for-help – to the new Nazi authorities in December 1938. Which had the hoped for effect.

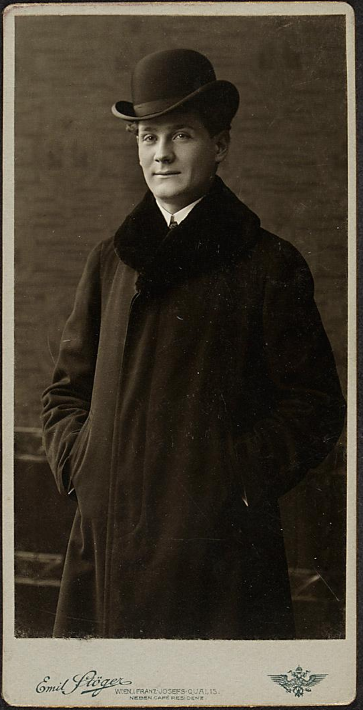

Actor Arthur Guttmann. (Photo: Emil Stöger / Theatermuseum Wien)

Still, an essay on “Lehár and the ladies,” including his wife Sophie, would have been interesting, certainly since Frey starts his own book with a quote from the 1911 novel Operettenkönige which anonymously recounts the backstage goings-on at Theater an der Wien, including a composer (= Lehár) and his unsuccessful amorous pursuit of the diva (= Mizzi Günther). You could take a lot of cues from Operettenkönige and ask how we might look at the operetta industry of the early 20th century with eyes wide open, like Laurence Senelick does in his essay “Sexuality and Gender” with regard to the entertainment industry of the 19th century. (For an interview with Mr. Senelick, click here.)

Franz Lehár and his wife Sophie as seen in “Life” magazine, 1947, shortly before their deaths.

But that’s not the path editors Heide Stockinger and Kai-Uwe Garrels take. To start right at the top of the list: allowing Michael Lakner to use his essay for blatant self-promotion, outlining what wonderful work he’s done as intendant of the Lehár Festival in Ischl and now at Bühne Baden, not just as artistic director but also as stage director, going into all the glorious details of his productions, is excruciating to read. Is Mr. Lakner trying to position himself for the job of new director of Volksoper Vienna with such a love letter to himself?

The Lehár reader “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz.” (Photo: Böhlau Verlag)

A blow-by-blow analysis of his stagings – such as Zarewitsch – would be fitting for a program booklet in the theater, but it has no place in such a jubilee reader. Because who cares whether Mr. Lakner relocated the action of Zarewitsch “to the fitness studio of the heir to the throne”? And to mention all the prizes Mr. Lakner won for his work – such as the “Frosch” handed out by the Bavarian radio program Operetten Boulevard – it the icing on this indigestible cake. It makes Norma Desmond look almost sane, by comparison.

Stage and theater director Michael Lakner in 2018. (Photo: Bernhard Holub / Wikipedia)

If this essay is an all-time low point, then next in line is an essay on the “Italian” side of Lehár, namely his 1920s success La danza delle libellule. Instead of explaining what the Viennese operetta industry has to do with Italy, and how the Italian operetta scene functioned in the early 20th century in relation to Vienna, you get a summer holiday report by Eduard Barth who writes about his visit to Trieste in 1982 where he saw the aforementioned Danza delle libellule. He describes the imposing historic buildings of Trieste, the blazing summer heat, the audience waiting for coffee and ice cream in the historic theater, he gives a bit of festival history (emphasis on “a bit”), and that was it. Can this be for real?

In other essays other individual shows are discussed, among them Friederike. Why that show and not any others? No explanation is given.

There’s an interesting text by Helga Maria Leitner about the Lehár villa in Ischl which is now a museum. Leitner is the former press officer of the Lehár festival, i.e. a former employee of Mr. Lakner.

She gives a detailed account of the history of the villa, its various previous owners, and how the rooms were furnished by Lehár. It all seems very serious and pious. And when we get to Lehár’s bed room we read that it’s filled “with countless religious paintings and artifacts” which create “an atmosphere that is stuffed, dark, even oppressive.” We learn: “It shows Lehár’s deep religiosity which closely connected him – throughout his entire life – with his mother Christine Lehár, née Neubrandt.”

Lehar in his study in Ischl, at the piano in 1910. (Photo: Die Villen von Bad Ischl/Amalthea)

Of course this Lehár reader does not offer the photo of Lehár in his Ischl work space (seen above), which is included in Marie Therese Arnbom’s volume on the villas of Bad Ischl. There we see the composer sitting in front of a rather different kind of picture that probably didn’t remind him of his dead mother. And if it did, that would certainly be worth an extra essay. (To read more about Marie-Theres Arnbom’s Ischl book, click here.)

Cover for the book “Die Villen von Bad Ischl,” published by Amalthea.

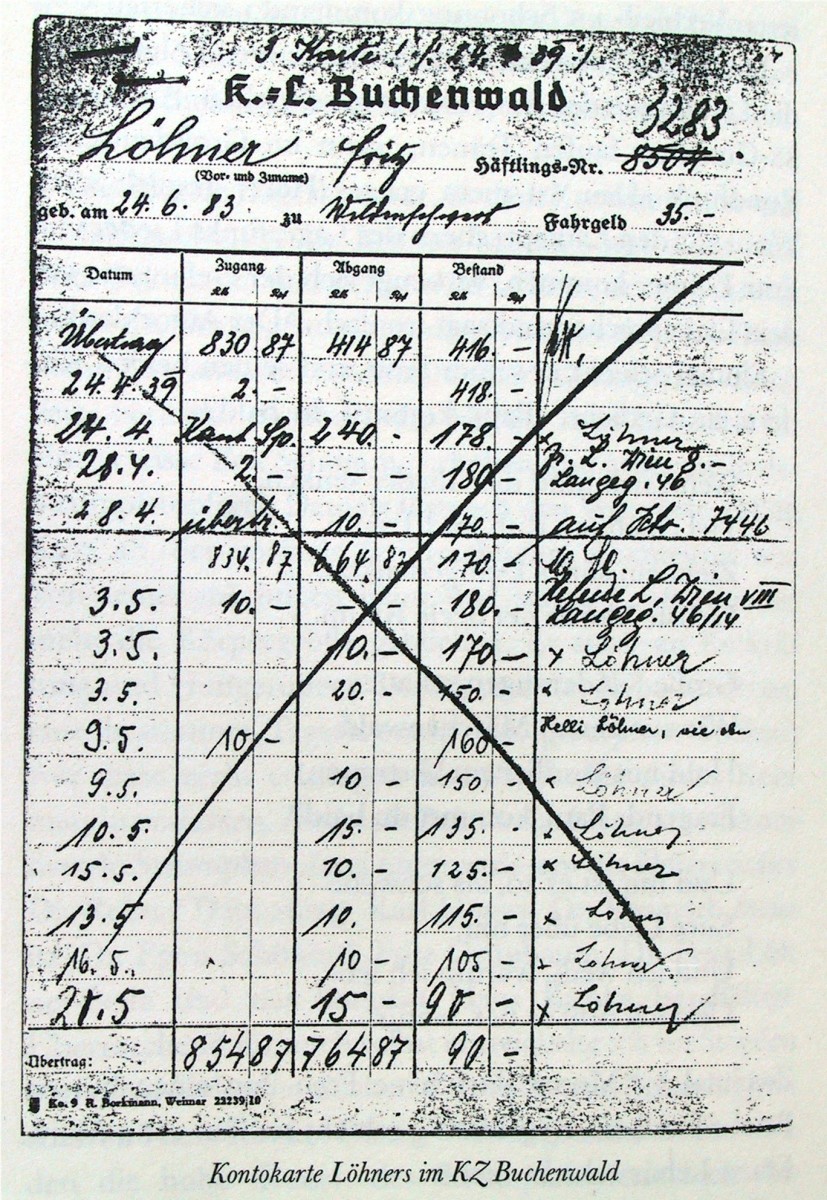

Special mention should go to Wolfgang Dosch and his chapter “Franz Lehár und sein Rastelbinder.” On the one hand, it’s an interesting account of how the Nazis tried to create a new version of that early success in the 1940s – a new version in which the Jewish title character (originally played by Louis Treumann) was turned into an “Aryan” hero. Things get rather complicated when Mr. Dosch moves on to explain that the “braune Nachrede” (i.e. slanderous Nazi rumors) that surrounded Lehár after 1945 are unfounded. With special attention given to the infamous accusation that Lehár was “the man who let Fritz Löhner-Beda die in a concentration camp.”

The concentration camp registration card of Fritz Löhner-Beda who died in Auschwitz.

Obviously, the topic Lehár and the Nazis is a complicated one, and there are no straight forward answers. This is blatantly evident when you read the respective chapters in Stefan Frey’s new biography, it was also evident in Immer nur lächeln … Das Franz Lehár-Buch edited by Ingrid and Herbert Haffner as far back as 1998. Trying to clear Lehár of all “guilt” by quoting sources such as Einzi Stolz, Bernard Grun, Heinrich Mann, Paul Knepler and many others doesn’t seem the right way to move ahead here, at least I find it highly problematic.

It would be worth asking why the people quoted by Mr. Dosch gave their pro-Lehár statements at the time they did, i.e. in the 1950s and 60s. And also ask how openly the operetta scene in Austria, Germany, and elsewhere discussed such political aspects at any given time – and how things have changed in recent years? It’s an important topic, but I’m afraid this is not an important contribution to that discussion. And I say this with great respect for Mr. Dosch.

Which leaves me wondering: why and who? Why did Böhlau bother to publish such a collection of essays that are out of sync with almost every current research? And who is such a book aimed at? Is this meant to be sold at the Lehár Festival in Ischl, in Baden, in the Lehár museum to unsuspecting visitors who want business-as-usual to not rock the boat?

In the end, it’s sad that a collection of essays in English hasn’t been published to widen the readership and open up the Lehár discussion. Because many English language operetta fans are completely unaware of the various new aspects that recent Lehár research has brought forward. On the other hand, Anglo-Americans have books such as Reframing the Musical, but they did not yet get a book Reframing Lehár. It’s high time, because a lot has been published here in German, but a proper reframing essay collection is still on the to-do list here, too.

The book “Reframing the Musical” is a collection of essays that look at the genre in terms of race, culture and identity.

Till there is a Reframing Lehár book in English, you might wonder whether this seriously is Upper Austria’s idea of presenting themselves as a “Kulturland” and spending public money on the self-promotion of a megalomaniac operetta “crusader” like Mr. Lakner, to help his future career in Austria: in a book edited by his partner, Mr. Garrels, who also worked as dramaturg at the Ischl festival. And let’s not forget an introduction by Christoph Wagner-Trenkwitz (“Mein Lehár”) who says thank you to Mr. Lakner for allowing his wife Cornelia Horak play a role in the production of Zigeunerliebe in Baden at the summer festival. Mr. Wagner-Trenkwitz also got to play a role in that production which Mr. Lakner calls “a fresh and daring new approach [to the Lehár show] with a sparkling, witty new text version” and a staging that appealed to a “contemporary audience used to musical comedies.”

Keep it all in the family – and never mind what’s going on out there in the “other” operetta research world? It seems so. And get tax payer’s money for it? Felix Austria.