Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 June, 2015

Anyone who has walked into a bookshop in the USA recently will have noticed that Ethan Mordden’s attractively packaged Anything Goes is out in paperback. Grandly subtitled “A History of American Musical Theatre” it is especially interesting because it contains large chapters on early operetta on Broadway – from the first Offenbach performances in the 1860s and Lydia Thompson’s burlesques, to Gilbert & Sullivan and The Merry Widow in the early 20th century to Romberg’s and Friml’s spectacularly successfull works in the 1920s. For that alone the book deserves three cheers from us here. But is it worth reading what Mordden was to say if you analyze quality rather than quantity?

The cover of Ethan Mordden’s “Anything Goes.” (Oxford University Press)

First off, Mr. Mordden writes very fluently, so it’s easy to see why he’s something of a “pop journalist” among modern musical theater writers. And he has a few outspoken fans in the theater community, such as e.g. Peter Filichia who greatly admires Mordden. Amusingly, Mordden states in his preface that he interviewed as many eye witnesses as possible, so that many of his stories are (apparently) detailed first-hand accounts. When you then turn the page, though, he starts with The Black Crook in the 1860s and you wonder: who exactly did he interview for this section? The same could be said about the following pages on opéra bouffe etc. I doubt that even the original The Student Prince production has many surviving cast members today. But I could be wrong about that.

What distinguishes these early shows is that they all move easily between operetta, vaudeville, burlesque, melodrama, comic opera, farce …. The singers left one show and appeared in another, as did the composers and producers. It’s a gigantic mash-up that set free great creative energies. Yet Mr. Mordden has a problem with that. His aim in Anything Goes is to differentiate “musicals” from “comic operas,” and he falls into the traps of not really knowing what to do with “operetta.” It’s inconceivable for him that operettas, in New York or elsewhere, are not necessarily “comic operas” but just as stylistically flexible as musical comedies.

So, as amusing as some of the chapters are to read, on Offenbach, on Victor Herbert, on Lehár’s Widow, on the Desert Song and Rose-Marie, they sometimes make my hair stand on end when Mordden forces his present-day perception of “romantic operetta” upon these shows!

“Irish-accented Bobby Gaylor sings ‘On a Pay Night Evening’ in the title role of ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ way back in 1903.” From Ethan Mordden’s “Anything Goes.” (Oxford University Press)

He quotes extensively from various standard books on the subject(s), often forgetting to say where exactly his information comes from. Anyone familiar with the writings on this particular segment of theater history will recognize where the elements come from. At the end of Anything Goes, there’s a long narrated “recommended reading list.” Funnily, nearly everyone around get’s a mention there, except Kurt Gänzl. Even though some of Gänzl’s more distinct passages about the “zaniness” of opéra bouffe find their way into Mordden’s narrative. I found this surprising, because Gänzl’s Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre would surely have deserved at spot in Mordden’s reading list, not to mention various other more general books by Gänzl. But perhaps they are too much competition, and too similar to what Mordden is writing himself? (I don’t know the answer to that question.)

Dennis Kings playing the beggar-poet Francois Villon in Friml’s “The Vagabond King.” From Ethan Mordden’s “Anything Goes.” (Oxford University Press)

Basically, Mordden doesn’t have anything substantially new to say about operetta, and his research is sloppy, to say the least. He gets a great many things that would deserve detailed analysis and description mixed up, probably because he doesn’t care too much to ponder the special nature of operetta – and form his own opinion, rather that recycle previous material.

But – this needs to be said – it is great that such an attractively designed “American Musical Theatre” book should give so much space to operetta, and not start with Show Boat (1927) and move onwards from there. Mordden’s argmuments as to why Show Boat is not an operetta are somewhat amusing in themselves, and exemplary to his misunderstanding of the older genre. But still, this is a fun read. And truth be told, it’s a lot easier to read Mordden’s account than, let’s say, Gerald Bordmann’s American Operetta. (Which has a few problems of its own.) The same might even be said with regard to Richard Traubner’s famous book Operetta. (He too looks at the genre from the romantic and comic opera perspective.) Without doubt, Anything Goes will make you want to dig out other books as explore certain aspects further. So it’s nothing if not stimulating.

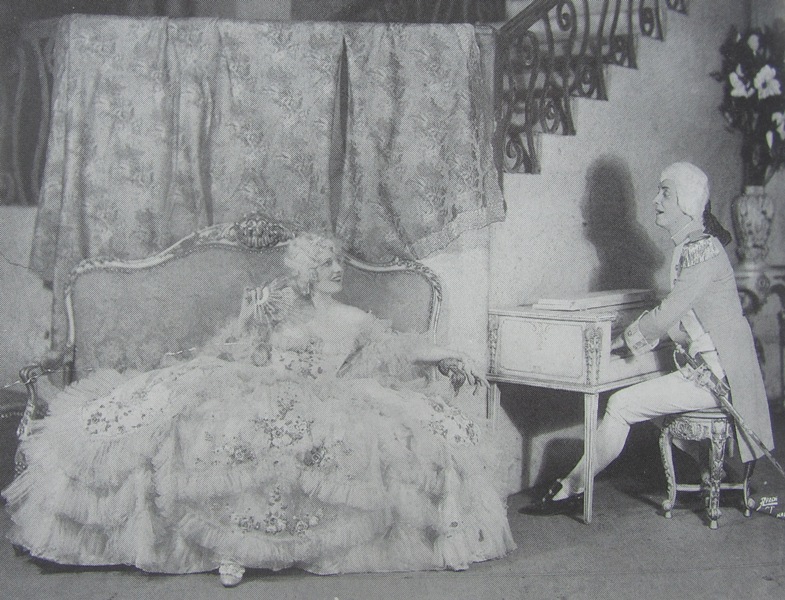

Sets by Donald Oenslager and costumes by Charles LeMaire for “The New Moon,” the Romberg operetta hit. From Ethan Mordden’s “Anything Goes.” (Oxford University Press)

There are a few photos printed in the middle section of the book. They are randomly placed there and don’t tell a story in themselves. This random quality of the images mirrors that of the text. For those familiar with the other writings of Ethan Mordden, this will not come as a great surprise. The only surprise is: why does Mordden actually get to publish one such book after the other, without anyone forcing him to pay more attention to the details? This one comes straight from Oxford University Press, after all. Not some no-name non-respected publishing house.