Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

16 November, 2021

No, the orientalist silent film orgy Sumurun, filmed in the Ufa studios in Berlin-Tempelhof in 1920, doesn’t need to be re-introduced anymore. Because its director, Ernst Lubitsch, is a legend and world famous for the “Lubitsch Touch” with which he later staged operettas such as The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) or The Merry Widow (1934), not to mention comedies such as Ninotschka (1939) or To Be or Not to Be (1942).

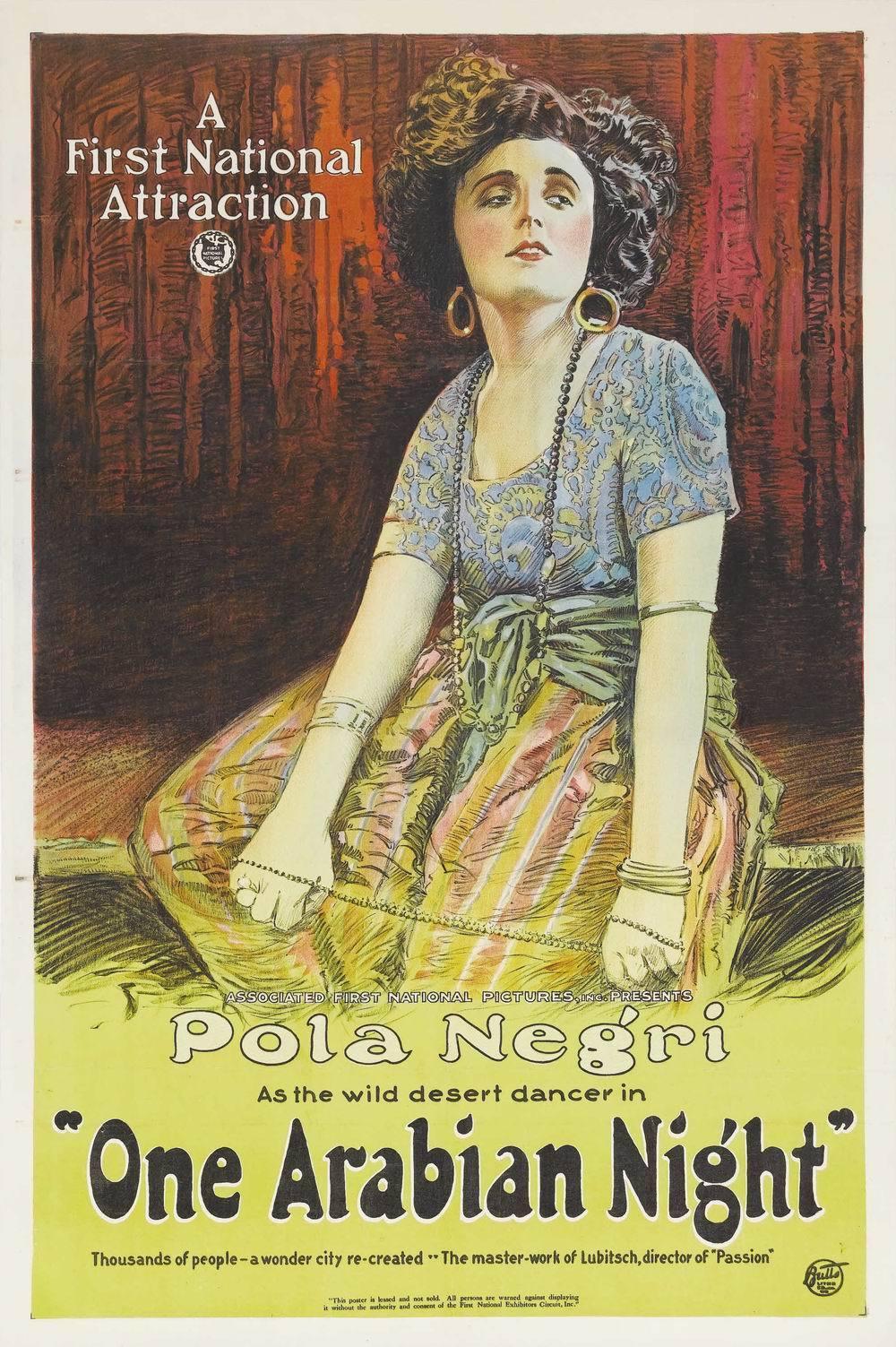

Poster for the English language version of Lubitsch’s “Sumurun”, 1920.

Before the man from Berlin’s Jewish Scheunenviertel “ghetto” left for California, he had demonstrated, after the First World War, how brilliant he was at staging historic costume dramas: Madame Dubarry (1919), Sumurun and The Pharaoh’s Wife (1922). Productions with a large budget, even bigger stars, lavish live music and a lot of bare skin. Rick McCormick addressed this in his 2020 book Sex, Politics and Comedy, subtitle: “The Transnational Cinema of Ernst Lubitsch”.

The cover for Rick McCormick’s “Sex, Politics and Comedy: THe Transnational Cinema of Ernst Lubitsch.”

The composer of Sumurun, on the other hand, definitely needs introductions, because nowadays he is almost exclusively mentioned in connection with his famous son. So here he is: Victor Hollaender. He was one of the most successful entertainment composers before the First World War, who returned to Berlin after first career stops in Milwaukee and London, and he had his breakthrough as the house composer of the Metropol Theater, today’s Komische Oper. There he wrote legendary “annual” reviews: Auf ins Metropol!, Ein tolles Jahr, Das muss man seh’n und Die Nacht von Berlin.

Victor Hollaender at the piano, in 1906. (Photo: Collection Universität Osnabrück / Wiki Commons)

These shows contained hits like the “Schaukellied” or “Die Kirschen aus Nachbars Garten”. With texts that had to be submitted to the censor. As a result, any form of political protest or sexual permissiveness had to be cleverly hidden. So that the performer could play with the subtext!One of Hollaender’s greatest successes in 1910 was the music for the dance pantomime Sumurun, which Max Reinhardt staged in the Kammerspiele of the Deutsches Theater. The Berlin press spoke of “narcotic music” that “led up from the primitive melodies of belly dance to the bright indulgence of ecstatic love violins.” The pantomime was so successful that Reinhardt went on tour with it. The New York Times also raved about the “extremely beautiful descriptive music”. Reinhardt filmed the play in 1910, but the film is considered lost.

Lubitsch, who completed his acting training with Reinhardt, had Victor Arnold as his teacher. Arnold played the hunchback in Sumurun – a study about love, where everyone lusts after someone who in turns lusts after someone else, which leads to jealousy and manslaughter. In 1920 Lubitsch set about filming Sumurun again. He took on the role of his teacher, who has since died, and mimed the hunchback himself, a tragic clown who longs for the self-confident dancer Pola Negri. Who in turn only has eyes for others – with money.

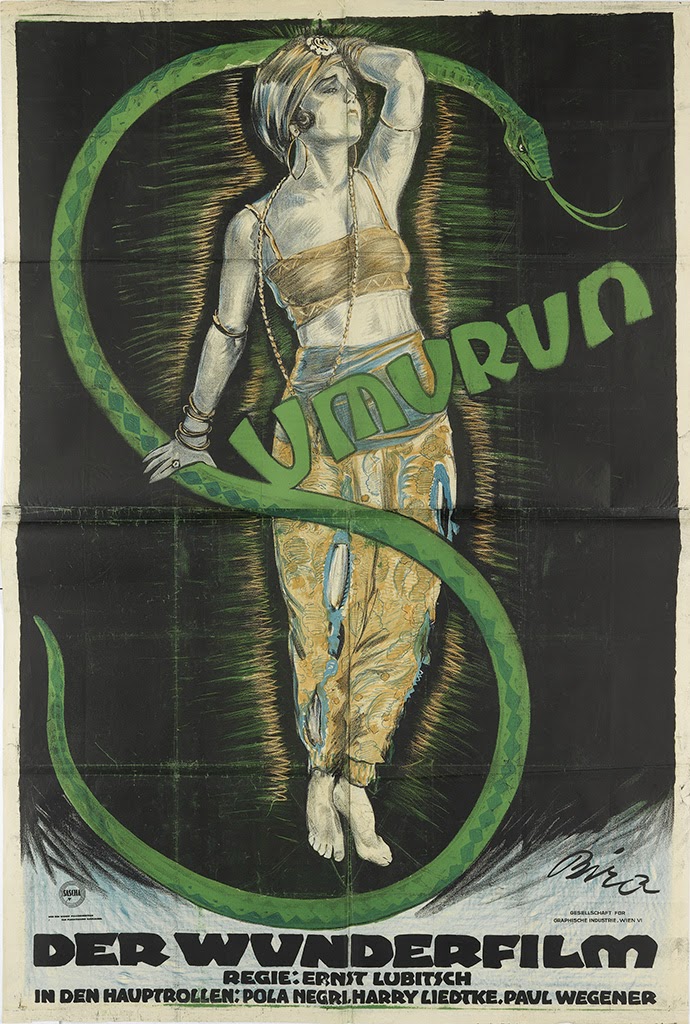

The “Wunderfilm” by Lubitsch: poster for the 1920 version of “Sumurun” with Pola Negri as the big star. (Photo: Poster design by Mihály Bíró)

In addition to a star cast, the 1920 film offered the tried and tested music by Hollaender. Played at the premiere by a full live orchestra. It was also published as a piano reduction by Ufa so that other cinemas could use it. The film was later restored by the Friedrich Murnau Foundation, but the original music could not be found. A different soundtrack can be heard on the currently available DVD. It was a coincidence that the silent film conductor Burkhard Götze heard from a colleague in 2020 that an old cinema fan had the piano score. And was willing to make it available.

Götze set out immediately to adapt the material to the surviving film version. And he re-orchestrated the piano parts for grand orchestra again. This version was been premiered by the Deutsches Filmorchester Babelsberg in Potsdam’s Nikolaisaal.

Conductor Burkhard Götze. (Photo: Daniel Wandke / Nikolaisaal)

And it was a sonically explosive experience, totally overwhelming. However, there were few people in the auditorium, probably due to the sky high corona infection numbers. So one has to hope that this fantastic new version of Sumurun will be performed again elsewhere and find its way to TV stations such as arte. As for Victor Hollaender, the Komische Oper completely ignored him in their revival project of forgotten Jewish composers who were important for the former Metropol Theater.

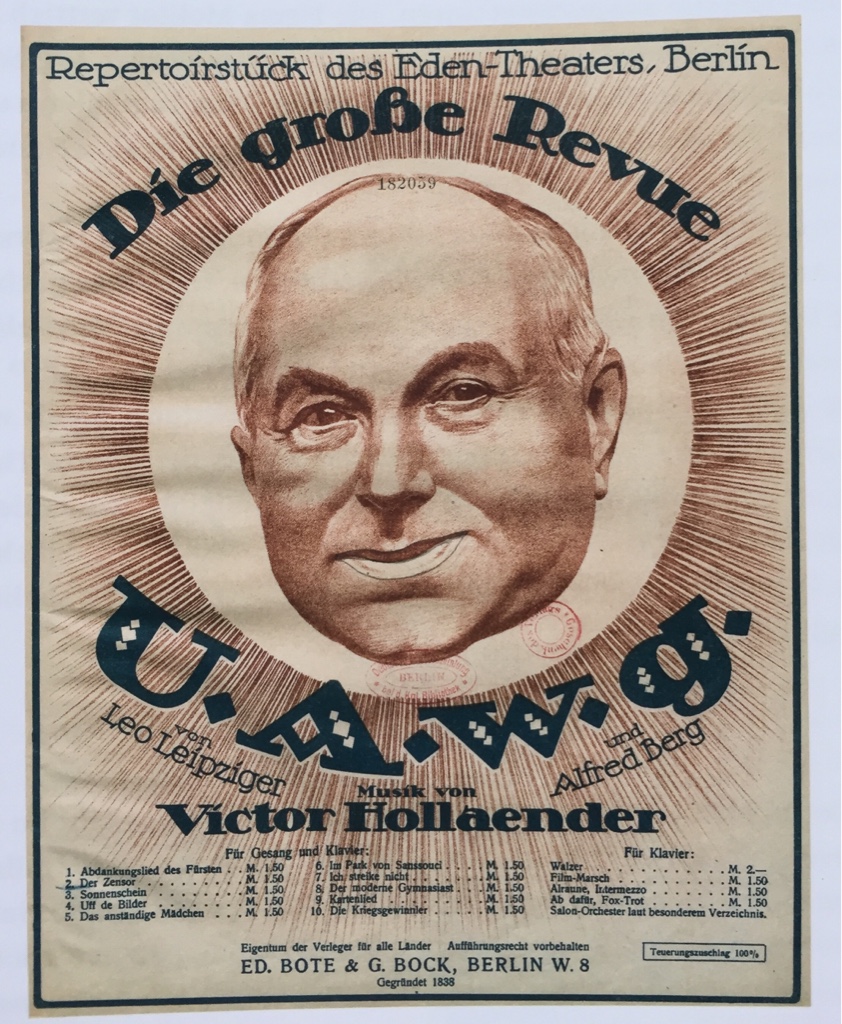

Sheet music cover for “Hurra, wie leben noch!!!” from a Victor Hollaender Metropol-Theater revue. (Photo: Bote & Bock)

The Berlin label Truesound Transfers released extensive original recordings of the annual reviews from 1905 and 1907 on CD, where you can hear stars such as Fritzi Massary, Joseph Josephi and Josef Giampietro in excellently restored versions. These CDs can sadly no longer be ordered, but they show that there are over 50 (!) Hollaender recordings from the beginning of the 20th century that sound noticeably different from the Peter Alexander “nostalgic” version of the “Kirschen in Nachbars Garten” (cherrys in the neighbor’s garden).

Hollaender’s last revue U.A.W.g. from 1919 was part of the recent exhibition Berlin in the Revolution 1918/19. In the catalog, Alan Lareau reports that Hollaender withdrew from the stage afterwards, making room for his talented son Friedrich. Victor promoted and shaped the latter’s career significantly.

The grand revue “U.A.W.G” with music by Victor Hollaender, 1919.

He wrote his memoirs under the title Revue meines Lebens, and it was again Lareau who edited that book for a re-publication in 2014. The result is a slim volume that was never followed by an independent biography. When we asked Mr. Lareau about this, he said he has given up banging his head against concrete walls.

In view of the anti-Semitic terror in Germany, Victor Hollaender left Berlin in 1934 and followed his son to Hollywood. Where he died in exile in 1940.

Victor Hollaender’s grave. (Photo: Robert Wennersten)

Although there is a lot of new interest in the German entertainment culture, Hollaender Sr. is still being ignored. The Sumurun concert in Potsdam is perhaps a turning point. Lareau published on the Milwaukee years. He also wrote about Hollaender’s burlesque operetta König Rhampsinit whose oriental theme is not dissimilar to Sumurun.

Cover of the piano-vocal score to the operetta “Rhampsinit” (König Rhamsinit), which was first performed in Milwaukee in 1891. (Archive Alan Lareau)

Perhaps the new artistic management at Komische Oper will add Hollaender to their program after Kosky’s departure. Perhaps a publisher will finally commission Lareau to publish the Victor part of his Friedrich Hollaender biography separately. It’s more than high time to finally overcome the total erasure by the Nazis and honor this man, again, as the voice of Berlin before the Roaring Twenties.